|

|

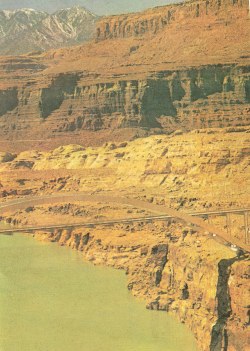

Utah:Natural Setting, Recreation, Archeology and Indians, Agriculture

Several other peaks in the vicinity have an altitude of more than 11,000 feet. The Wasatch Range terminates near central Utah, but the Sanpitch, Pahvant, and Tushar plateaus continue southward and merge at length into a broken table-land, which extends across the Arizona line. The Henry, La Sal, and Abajo mountains rise out of the southern plateau. In the Tushar Plateau near Beaver there are three 12,000-foot lava peaks. Extending eastward from the Wasatch Range, and covering most of northeastern Utah, are the Uinta Mountains, where Kings Peak, the highest point in the State, towers to an elevation of 13,498 feet. South of the Uinta Range is the Uintah Basin, an east-west valley bordered by sloping mesa lands. Southeastern Utah is an immense broken plateau extending in a triangular form over nearly one-third of the State's surface. Most of this region is too rugged for agricultural use, and only a small part has enduring settlements.

Recreation

UTAH people are said to be the greatest campers and picnickers in the world. Nearly every family has a smoke-blackened coffee pot and skillet, a brace of wire grills, a set of oversize spoons, and tinware suited to rough usage and large helpings in the open. The geographic basis for this proclivity is easy to find. Utah is an arid State, and nearly everybody, whether a city or rural dweller, lives at the mouth of a canyon, from which the family-size or city-size water supply is obtained. On hot summer evenings or weekends it is customary to toss a camp or picnic outfit in the family car and go where canyon breezes blow, or where increased altitude provides relief from the heat. The ten national forests and the eleven national parks and monuments provide recreation for residents mainly in proportion to their distance from populous centers, though more distant areas have a way of achieving popularity for hunting and fishing.

The Wasatch National Forest, being nearest to Salt Lake City, draws most visitors--in the neighborhood of 200,000 every year. About 150,000 Of these are picnickers, spending only a day at a time; most of the remainder are weekend campers. The forest is also popular as a summer home site, and for fishing and winter sports. The four widespread units of Fishlake National Forest attract more than 110,000 visitors per year, and serve the recreational uses of a considerable population in southern Utah. As the name indicates, it is the most popular fishing area, and has the greatest number of hotel and resort guests. Cache National Forest, checkered about the northern end of Utah's population axis, draws more than 75,000 visitors yearly, and has the largest concentration of summer cottages. Minidoka National Forest, in the northwestern corner of the State, has only 600 or 700 visitors a year, most of them hunters.

Archeology and Indians

MANY centuries before the dawn of the Christian Era, roving bands of Old World hunters were already crossing the icebound waters of Bering Strait to the uninhabited North American continent. Some of these early groups undoubtedly reached the Southwest, for, in such localities as Folsom, New Mexico, Gypsum Cave, Nevada, and the Lindenmeier site in Colorado, their chipped points and other artifacts have been found in association with the bones of prehistoric bison, camels, sloths, mastodons, and other animals. These early comers did not possess a highly developed culture. They knew the arts of stone chipping and fire making and, possibly, used spears propelled by the atlatl (a notched stick used to increase the velocity of a hurled spear), employed bone awls for piercing and sewing skins, and owned domesticated dogs. They had no pottery or agriculture; nor did they, as far as is known, have any form of permanent habitation other than natural caves.

The earlier inhabitants of Utah were probably a group comparable in most respects with those whose artifacts are found in other parts of the Southwest. So far little information concerning them has come to light. Caves along the shore line of Great Salt Lake's predecessor, Lake Bonneville, have yielded objects the antiquity of which extends back several thousand years, although they were not necessarily left by the first human inhabitants of Utah. Flint points, knives, bone awls, and flint scrapers attest the presence of primitive hunters.

About the time of Christ, the inhabitants of the San Juan, Paria, Virgin, and Kanab river valleys began to raise corn. This marked the beginning of the long development of a culture known as the Anasazi (Navaho, the Ancients), which was distributed over northern Arizona and New Mexico, southwestern Colorado, southern Utah and Nevada, and southeastern California.

Agriculture

SYMBOLICALLY, the first act of the Mormon pioneers, when they entered Great Salt Lake Valley in 1847, was to plow the soil. When plowshares broke in the sun-baked earth, the settlers flooded the land with water from City Creek. The next day they planted potatoes. That was the first farming by white men in Utah. The system of Mormon settlement, in agricultural villages and communities, brought farmers in from their acres each evening, where they could "swap" experiences and theories with their neighbors. This system has not materially changed; Utah farmers in 1940 are still preeminently village dwellers, with social, economic, and religious life centered around communities. There are some 30,000 farms in Utah, about half of which are in the six counties adjacent to Salt Lake City. Because of this concentration, in reach of electrical lines, Utah is fifth in the nation in percentage of farm homes wired for electricity.

Of the total area of the State, only 3.3 per cent is tilled land, and about 1 per cent is dry-farmed. Much more land could be farmed if water were available. Most of the irrigable land was under cultivation at the close of the nineteenth century, and the farms, never large, have since been subdivided among large families. Third and fourth generations today face the problem of making a small farm of 20 acres or less support a family.

Utah soil, like that of other arid States, is exceptionally rich in plant foods--there has never been abundant water to carry away the minerals necessary for plant growth. Some Utah soils are 60 per cent limestone, and with limited rainfall and careful irrigation may never require additional lime.

|

|||

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.