|

|

Iceland

By Dore Ogrizek

THE first time my readers heard of Iceland was, in all probability, through Jules Verne, and most of them throughout their lives will have learnt little more than this Journey to the Centre of the Earth could teach them. Who could fail to remember that Professor Lindborg, his nephew Axel and their guide Hans went down the crater of one of Iceland's innumerable extinct volcanoes in order to reach the "centre of the earth", following the advice of a very ancient Nordic scholar's Book of Magic? Two hundred years before Jules Verne, the Danish writer Ludvig Holberg made his hero, Nils Klim, follow much the same route -- he too plunged into the bowels of the earth from a grotto near Bergen. But the Subterranean Travels of Nils Klim, a book on the lines of Gulliver's Travels, was, like Swift's masterpiece, satirical in aim, as are nearly all Holberg's writings, from his comic epic Peder Paars to his plays in which he so wittily derides his contemporaries' absurdities. Jules Verne's book makes no pretence to be anything more than an honest adventure story and, as regards Iceland, he gives us in a few pages a very accurate and striking picture of that extraordinary country.

There is no more magic, more bewitching land in Europe. Nowhere else, not even the extreme north of Norway, fascinating as it is, gives so deep an impression of estrangement, complete and utter estrangement. Even in Reykjavik, capital of the island, which could resemble a Norwegian or Swedish town, one feels oneself confronted with something quite different. The inhabitants have a character of their own, and in modern as in ancient literature, books by Icelandic authors have their own local colour; in an undefinable way they bear no resemblance to anything in the world. If we stop and think what Iceland represents, if we imagine that immense block of ice crested with volcanoes, pierced with springs of boiling water that shoot up to tremendous heights, a land where life is possible only on the coast -- and not on every section of the coast -- we can well understand why men born on this smoking, trembling soil, in a climate severe in the extreme, are modelled in a different clay from those who grow up in temperate climes. They have about them something of the volcanic character of their native island. No doubt they never experience that strange feeling of uneasiness which often overcomes the traveller when he finds himself up against a countryside so desolate as to be inhuman. There are landscapes of this nature in certain parts of Norway: in the Lofoten Isles, in the deserted valleys of Jotunheimen, the "giants' home," in front of certain immense glaciers where water oozes forth in trickles with a thousand mysterious voices; but in Iceland the country as a whole -- almost the entire island, in fact -- is made up of landscapes such as this. It would, I think, take a long initiation before anyone born elsewhere could rid themselves of this mysterious, indescribable uneasiness. Once this barrier has been crossed one is full of admiration for the impressive scenery, which always has a mysterious, tragic quality, but underlying this admiration is a feeling of terror: the terror that men from temperate climes always experience when faced with nature in the raw, where human beings seem out of place in landscapes made for monsters and Titans. This lack of common measure between the Icelandic landscape and the stranger surveying it is one of the reasons that he is overcome with awe, even away from the famous volcanoes or geysers which have so often been described. The island's soul provides sensations never felt elsewhere: it exudes a charm built of barbaric grandeur which is, perhaps, as intense as and similar in nature-to that of the Asian or African desert.

The very name "Iceland" warns us that it is a world apart with a face of its own, and that, although inhabited by man, it obeys the same laws as the immense uninhabited or unexplored Arctic regions. Let us not forget -as geographers take care to remind us -- that this island, the largest in Europe after Great Britain, is on the fringe of the glacial Arctic Ocean, that it extends over 39,000 square miles and that its immense surface contains only one hundred and fifty thousand people, making a little over two inhabitants per square mile. Its capital, Reykjavik, alone absorbs more than a third. The remainder of the population is dispersed in little towns, all situated near the coast -- mainly the west coast -- in villages nestling at the foot of fjords which cut deep into the coastline in capricious curves, and in isolated farms. These villages and farms are built in the plains where the mild climate lends itself to pleasant vegetation, as in the Ásbyrgi region for instance, and where the eye and mind can wander freely amidst green fields and dense forests, immediately after crossing the basalt wall of Hljódaklettar, resounding with voices (its name, in Icelandic, means echoing rock). I hasten to add that Icelandic is a language on its own, whose raucous, harsh and brutal consonance is in harmony with the general appearance of the countryside.

On leaving the very hilly coastline, one comes upon a basalt plateau, not very high, furrowed with crevasses and outcroppings of lava which have been piling up here for millions and millions of years. Beyond the plateau enormous glaciers outstretch, often inaccessible and immense -- everything in Iceland is immense-to such an extent that in comparison the most widespread Norwegian glaciers, even the colossal Folgefonni, look like toys. Some of these blue-green immensities, the tremendous Vatnajökull for instance, measure as much as 9,500 square yards. The figures speak for themselves, although in Iceland one becomes accustomed to considering a thousand as a sort of basic geographic unit for the country. Finally, behind the glaciers, lifting their pyramids high into the sky, as often as not swaddled in cloud or fog, the gigantic family of volcanoes of every shape and size rise one above the other, extinct for the most part, but liable to reawaken, as history bitterly testifies.

Hekla is the best-known of these volcanoes, as much for its majestic outline -- rarely perceptible, being invariably veiled in mist to which it owes its name ( Hekla means cloak in Icelandic) -- as for the frequency and violence of its eruptions. It is not the highest but the most regal and impressive, a kind of Jupiter in this Olympia of thundering mountains. Skaftárjökull is surrounded by an inferno of fathomless crevasses and tremendous hulks of lava which give it a ferocious appearance; but the

most terrible of all is, without doubt, Laki (was it so-named in memory of Loki, god of fire in Scandinavian mythology?), consisting basically of a family of hundreds of little volcanoes which, like a herd of hideous beasts, all appear ready to spit forth their burning mud and blazing cinders. Then we should mention Askja, the largest of these spiteful monsters seemingly impatient to revert to their untamed nature; also Öraefajökull, which, at 7,600 feet, is the highest, and Dyngjufjöll, whose hot cinders the Norwegians still remember receiving from an incredible distance during its last great eruption, nearly seventy-five years ago, I believe.

After all this it is easy for us to imagine Iceland as one boundless volcano, possessing thousands of mouths, distended with inextinguishable furnaces, concealing frantic activity beneath its ice and its treacherous tranquillity, seething in the melting-pot of the earth, seeking every possible way of gushing forth, even in the pacific, wonderfully spectacular guise of its famous geysers. One goes to Iceland to see the geysers -- for the volcanoes rarely show themselves off and are given a wide berth. The geysers, on the other hand, are the traditional attraction of the island and, after drinking them in with their eyes, travellers re-embark and move on towards more clement skies.

There are masses of geysers in Iceland, some more renowned than others, but all derive their name from the great Geysit -- the geyser No. 1 located near Laugafjall. I will not describe this well-known phenomenon, nor will I outline the theories by which scientists have explained this tremendous upthrust of boiling water, this fantastic, foaming, roaring column which, obeying certain mysterious laws, now rumbles ominously in subterranean corridors, now bursts forth in jets which can, in certain cases, reach as much as a hundred and sixty feet. There are geysers of all sizes, some of which are quite tiny, whilst others obligingly spray forth at the request of experienced guides who know how to stimulate their dancing jets of water at will.

One cannot know Iceland simply by contemplating Hekla from afar and guessing at its silhouette hidden in a clock of fog; nor by receiving the burning splashes of a geyser, big or small, from a respectable distance. Those are phenomena of nature for cruising tourists, who will marvel at them for a few minutes and talk of them for the rest of their lives. To understand the peculiar nature of this island of fire, with its wealth of rugged scenery, we must also go down into the grottoes of lava and ice at Surtshellir, not far from Eyriksjökull. Everything here is extraordinary and magnificent. We wander beneath high vaults, along wide corridors conjuring up pictures of fairy palaces and fabulous treasure troves lit by dazzling crystals. Then we must go through the narrow gorges of Almannagja, a pass of black basalt seemingly hollowed out of a monolith, and continue as far as the little natural lake called Drekkingarhylur, where a curious form of divine justice was once administered. When a woman was suspected of adultery she was thrown in the water and if she floated up she was considered innocent; if on the contrary, she sank, ipso facto she received the punishment she deserved. It is by no means certain that the most faithful women were the lightest, nor that the ill-fated pond was entirely infallible in matters of conjugal constancy.

Waterfalls cascading down glaciers and rocks are so numerous in Iceland that it is impossible to know them all. If you want to see the finest, you must go as far as the dazzling Jarlshettur region where Hvitá, "the white river," flows, and come upon it at the spot where it tumbles down the steep slopes of Gullfoss. The contrast between this frenzied white foam dashing from its rocky balcony, the glistening blackness of wet basalt, and the murky hollow that engulfs the roaring water is one of the liveliest and most moving of the countless impressive sights in this fantastic island.

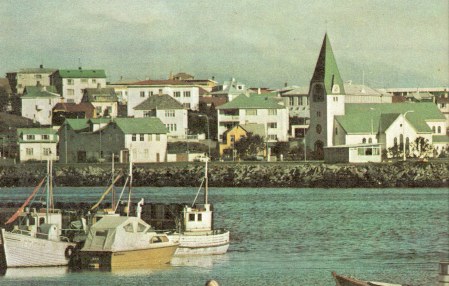

The towns, too, deserve a visit. First Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland and the centre of her administrative and intellectual life. Within sight of ice-fields and volcanoes, fishing harbour and trading port, enlivened by ships coming and going, Reykjavik is strange and complex in character, combining quiet familiarity with majestic grandeur. In recent years the city has been modernized and enlarged by the addition of new districts. Modest wooden houses rub shoulders with more solemn and imposing official buildings. Old houses are few, but there is an extremely interesting museum containing a collection of national antiques, a modern university, a theatre, and an extensive library which meet the cultural needs of Icelanders who are great readers, not only by filling in the leisure hours of their interminable winters, but also by satisfying the thirst for knowledge, the hunger for poetry so common amongst them.

Reykjavik and Akureyri suffice to give us an impression of Icelandic city life. Akureyri is one of the oldest inhabited sites: ruins dating back to the 13th century and the founding of the first convents in Iceland are to be found near there; nowadays it is no more than a lively fishing port, filled with the smell of fresh and salted herring. This west and north of Iceland is mainly remarkable for its deep, clear-cut fjords, similar to those seen in Norway, except that the surrounding countryside is more rugged. In contrast, the little gardens of Akureyri are appreciated all the more, tended as they are with loving care by the inhabitants of the town, who watch over their rare and precious flowers with maternal devotion.

Akureyri is the centre of an extremely interesting tourist region leading to Myvatn, nursery-garden of volcanoes which scientists have compared to lunar landscapes: there is that same desolate solitude, that same profusion of craters swarming round a huge lake of dead grey water between black basalt banks. . . . This brings us into the realm of giants and demons, but first we should spare a thought for the efforts man has put into this eviltempered, thankless soil in order to become acclimatized and to organize civilized life there. In this respect there are few Icelandic beauty spots more impressive than the Thing plateau. In the Middle Ages throughout the Scandinavian world, the assembly offree citizens was called Thing; its door was closed to slaves and serfs. It was there that matters of interest to the life of the community were discussed, there that sentences of banishment were passed condemning particularly intractable or dangerous individuals to rove for many a long month across the seas.

It is highly improbable whether there were any natives on the island when the first Norwegian emigrants landed. No trace of human settlement has been found prior to that of the bold pioneers who were the first to bring their dragon-headed barks into the Icelandic fjords and build their huts on the least inhospitable shores. These pioneers were clan chieftains who refused to submit to domination of King Harald Hårfagre "the Fairhair," whose reign was devoted to unifying his country. Before his rule, Norway was divided up amongst a number of princes and kinglets, proud of their independence, perpetually at war with each other to the great detriment of the country itself. Wishing to impose his authority on these turbulent tribal chiefs, Harald vanquished those who would not cede of their own free will, and condemned to banishment enemies whose ambitions threatened the peace of the kingdom.

These noble exiles, who preferred freedom on an almost uninhabitable desert island rather than submit to the will of an absolute monarch, founded the colony from which the majority of Icelanders descend. They established a form of republic whose government was in the hands of the Thing -- its function has already been described -- and their hyper-susceptibility, allied with a need to preserve intact, come what may, the freedom for which their ancestors sacrificed so much, have remained as the most outstanding characteristics of Iceland throughout the ten centuries that have elapsed since the arrival of Harald Hårfagre's first adversaries.

Political independence, intellectual independence (the majority, one might almost say the cream, of Nordic literature comes from Iceland), economic independence which brought her into conflict not only with English commerce but also with the German Hanse and Danish traders -such are the finest riches of Iceland, which she would not exchange for all the treasure in the world. Politically, she fell successively under the domination of Norway, then Denmark, but her personality emerged unscathed; as soon as she could, Iceland threw off the Danish yoke which, though not very heavy, interfered with her desire for independence. Allegiance to the Danish crown was progressively transformed first into a personal union by which the king of Denmark was at the same time sovereign of Iceland, then into absolute autonomy, which is the current regime of the island. As Bryce, one of the finest authorities on Iceland and her history, wrote, "During nearly four centuries it was the only independent republic in the world, and a republic absolutely unique in what one may call its constitution, for the government was nothing but a system of law-courts, administering a most elaborate system of laws, the enforcement of which was for the most part left to those who were parties of the lawsuits."

We should by no means imagine this 10th-century "parliament" as a noisy quarrelsome fray. Harald Hårfagre's exiles were rough warriors, to be sure, and intrepid sailors who feared neither tempests, nor the onslaught of monsters or sea-trolls which the Norwegian painter Munch has endowed with such terrible faces, but when they sat in the Thing, they brought a note of solemnity and equity worthy of the Greek Areopagus or the Roman Senate. In short, they realized the necessity for strict and scrupulous discipline, failing which the island's population would have stupidly killed itself off in interminable vendettas. As the sagas testify, vendettas were, in fact, one of the most dangerous reasons underlying the perpetual unrest that ruled in the Viking world; one had to live with a spear or an axe constantly within reach, for the only way of settling a quarrel was by promptly seizing the nearest weapon.

Consequently at sessions of the Thing, the administrators insisted above all that no one, whoever he might be, bring weapons to parliamentary meetings: they knew by experience that in the heat of debate anyone who had a knife at his belt would be tempted to draw it, and would surely not resist the temptation. At the end of the session everyone retrieved the weàpons he had left outside the Thing enclosure, but by then their nerves were calmed, and they were, besides, sufficiently disciplined to obey parliamentary decisions without demur. Those who refused to give way had one resource: to leave the community whose laws they no longer accepted, and go off as Vikings to run the risk of the seas. Thus it was that, whilst Europe was a prey to feudal anarchy, Iceland was a state admirably organized and administered, worthy to serve as model for the great states which were, in short, far less civilized. Since June 17th, 1944, Iceland has been an autonomous republic.

Bryce is thus perfectly justified in saying of Iceland: "The Icelanders are the smallest in number of the civilized nations of the world, . . . yet it is a Nation, with a language, a national character, a body of traditions that are all its own. Of all the civilized countries it is the most wild and barren, nine-tenths of it a desert of snow mountains, glaciers and vast fields of rugged lava . . . . Yet the people of this remote isle, placed in an inhospitable Arctic wilderness, cut off from the nearest parts of Europe by a stormy sea, is, and has been from the beginning of its national life more than 1000 years ago, an intellectually cultivated people which has produced a literature both in prose and poetry that stands among the primitive literatures next after that of ancient Greece if one regards both its quantity and its quality. Nowhere else, except in Greece, was so much produced that attained, in times of primitive simplicity, so high a level of excellence both in imaginative power and in brilliance of expression."

Source: Scandinavia: Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.