|

|

Turkey in Europe: Istanbul, Edirne, Gallipoli, Bosporus, Sea of Marmara

By Ellsworth Huntington, Samuel Van Valkenburg

Remnant of a great oriental empire, once reaching to the very walls of Vienna, Turkey in Europe now possesses a significance mainly commercial and no longer political. Only 9,000 square miles are left. Most of this area is comparatively unproductive. Outside of the Maritsa Valley the monotonous upland with its dry steppe climate, cold and often snowy in winter, is sparsely inhabited, and sheep-raising is the principal occupation. Even the coastal region along the Aegean, the Sea of Marmara, and the Black Sea is dreary and unproductive. The mountainous peninsula of Gallipoli along the Dardanelles is the strategic key to the Bosporus, as the World War again proved, but it is a region of little economic value. The really good part of European Turkey is a narrow strip close to the Bosporus, which is more rainy, more beautiful, more accessible, and far more populous than any other part of the country.

Outside of Istanbul, the former Constantinople, the only city of any size is Edirne (Adrianople). This small ancient community of oriental aspect was left by the recent wars in an impossible situation, virtually surrounded by Greek and Bulgarian territory, and its dwindling population evinces its economic decline.

All interests are focused in Istanbul, which has one of the most economically advantageous locations in the world. The narrow Bosporus, a drowned former river valley, down which a strong current still flows from the Black Sea, divides Asia from Europe. Its shores are protected by the rising upland against cold winds, and get more rain than the surrounding uplands. Accordingly these exhibit a different kind of vegetation from that of the steppes, typically Mediterranean but with more trees than elsewhere. The dark cones of cypress trees, the pink of Judas trees, and the yellow of locusts, together with the blossoms of fruit trees, join with an exuberant display of flowering herbage and with the songs of innumerable nightingales to make the shores of the Bosporus truly entrancing in the spring. Olive trees are excluded by the winter frosts, but snow never lies more than a few days.

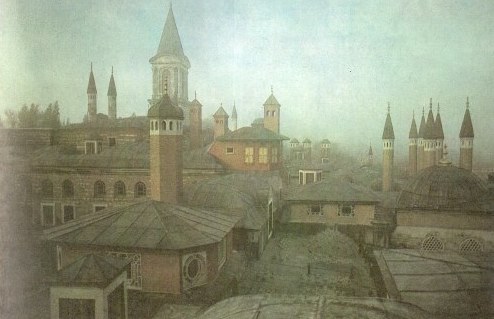

Istanbul is located where a small drowned tributary valley enters the southern end of the Bosporus and offers a safe harbor called the Golden Horn. Founded originally as the Greek settlement of Byzantium, this city, which was once the greatest in the world, became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. Then for centuries it was the stronghold of southern European culture against the forces of Asia. Later the invading Turks held it as their capital and made it the center of their empire. The catastrophic World War brought about its temporary decline, but despite the loss of its European hinterland, and the removal of the capital to the more centrally located city of Ankara, Istanbul is coming back. It could not be otherwise. Dominating the trade routes between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, where the old Danube roads cross over into Asia, the location has advantages of which it can never be deprived. The population is on the increase again, and there is every reason to think that Istanbul will hold a place among the cities of over a million. In Istanbul, unlike the rest of Turkey, both Greeks and Armenians still live in large numbers, although not so numerous as formerly.

The tonnage of vessels clearing and in transit is generally greater at Istanbul than at any other Mediterranean port. The city is still the great commercial port of Turkey and has dealings with a large part of western Asia. Imports from the United States include leather, cereals, motor cars, and agricultural machinery. Exports comprise mainly tobacco, silk, pelts, wool, furs, and opium. The United States purchases little except tobacco.

Today Istanbul is in a curious state of transition. This is typified by the fact that automobiles have to go very slowly over the Galata Bridge across the Golden Horn in order not to run down hamals or men who make a business of carrying loads on their backs. Equally typical are the rowboats which ply for hire on the Bosporus, and the old-fashioned ferryboats which carry passengers to suburban homes along the Bosporus and the Sea of Marmara. Everywhere one sees such contradictions as a superb museum on the one hand, and many valuable monuments of antiquity lying unprotected in the grass on the other hand. The old, narrow, crowded, noisy bazaars with their curious smells and their craftsmen clanging away at copper kettles, cutting out shoes from odoriferous leather, or setting out all sorts of curious dishes in the open air to tempt the palate, are in strong contrast to excellent stores and fine hotels run in the most modern fashion. Old Greek and Roman walls and pillars, early Christian churches among which St. Sophia is the chief, and medieval mosques with their great domes bring to mind the ancient greatness of the city. Huge palaces, used now as government buildings or left to fall to pieces, join with the roughly paved streets, the slow electric cars, and the leisurely Bosporus steamers to suggest the conflict between the old and the new in the last century. And a modern university, the American colleges on the Bosporus, the offices of business firms from western Europe and America, great tourist steamers, and an eager, forward-looking spirit among the young Turks show what is happening today.

Source: Europe

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.