|

|

Paris: Famous Places as seen by Great Painters

By Pierre Courthion

Paris is a city where nature has never worn out her welcome, but continues to thrive even in the ultra-modern quarters. The Seine with its shady banks and sunny quays provides a perfect haven of flowers and greenery, while the whole city is dotted with parks and gardens. The Impressionists and after them the Fauves roamed Paris with eager, understanding eyes, recording the tremor of the trees along the avenues, the shimmering surface of the river, old walls glowing in the sun, chimney smoke gathering into wisps of cloud above the rooftops. On monuments mellowed by time the faintest shades of color flicker as if seen across a tenuous veil.

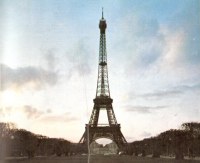

This unique light of Paris, made of sunshine and mist, gives every element its rightful place and tone in the panorama. Even the Eiffel Tower, modern times' great contribution to the silhouette of Paris, blends with the monuments of the past, a soaring, bodiless piece of architecture giving the full measure of the sky above the city. The best painters of the present day no longer linger over anecdote and detail; their broad synthetic vision embraces the seen and unseen treasures of a city as rich in past glories as it is rich in promise for the future.

The earliest paintings in which we can identify actual views of Paris date from the transitional period from Romanesque to Gothic, when outline drawing was coming back into favor at the expense of the monumental style. Definitely on the way out were the lavish gold backgrounds we find, for example, in the Psalter of St Louis, in which the scenes take place beneath the pinnacles, rose-windows and pointed arches of the SainteChapelle. Manuscript painting moved on from blue-and-red to shadings of color, to lively, freehand drawing, to the checkered backgrounds typical of the Parisian ateliers.

The Life of St Denis, a manuscript written by a monk named Yves and offered in 1317 in three bound folios to Philip the Tall, was illuminated by an unknown artist. The entire legend of St Denis, first bishop of Paris, is illustrated in detail, from the time when, still a pagan, he ranked as one of the leading philosophers of Athens, to the days of his conversion and subsequent mission to Paris where, with his companions St Rusticus and St Eleutherius, he suffered martyrdom on the hill of Montmartre; from there, says the legend, carrying his severed head in his hands, he walked a few miles northward to the village of Catulliacum 10, today called St Denis.

Each scene of the saint's life is coupled with vignettes which, taken together, give a remarkably complete picture of life in medieval Paris. We see boatmen on the Seine ferrying barrels of wine, and an angler in his boat drifting with the current. At the foot of the towers, beneath the city gates, we see the crowds on the Grand-Pont: money changers, goldsmiths, street porters, jugglers, showmen with bears and monkeys, beggars, rag-pickers, wine-hawkers--an image of everyday life in Paris that was to change little for many centuries to come.

Between these early works and the high achievement of the Limbourgs and Jean Fouquet, what do we find? The great intervening figure is that of Jean Pucelle, leading chef d'atelier of a Paris that even then, in the 14th century, was an international art center, a hive of busy studios where expert draftsmen and illuminators produced a wealth of exquisitely illustrated manuscripts. Pucelle's finest work is the Belleville Breviary, whose vellum margins he covered with ivy sprigs and foliage, with butterflies, dragon-flies and snails, and a whole fauna of whimsical creatures painted with a finesse and poetic realism that recalls "both the edge of a garden patch and a masterpiece of the engraver's tool"

Shortly after Pucelle's death in 1380 (the same year in which Charles V died), there occurred the revolt of the Maillotins 12, during which the furious populace lynched the tax collectors. Even so the city preserved a semblance of good government for the next thirty years, and it was with a heavy heart that the great satirist and ballad writer Eustache Deschamps took leave of Paris and the pleasures she offered:

Adieu m'amour, adieu douces fillettes,

Adieu Grand Pont, hales, étuves, bains,

Adieu Paris, adieu petits pastez!

Deschamps died about 1406. In the coming years Paris endured rioting, epidemics, famine, and an English occupation. But this did not prevent such proud lords of the realm as the dukes of Anjou, Burgundy and Berry, brothers of Charles V, and Louis d'Orléans, his youngest son, from patronizing artists and collecting works of art as passionately as Charles himself had done. Their vast estates, despite the troubled times, were covered with palaces, castles and chapels in which jewels, tapestries, sculptures and paintings from all corners of Western Europe were amassed--collections of incalculable richness as is proved by the inventories of the time. The most famous and memorable of these art-loving princes is the Duke of Berry.

A strong-minded man, avid of novelty and refinements, the Duke of Berry was continually on the move from one of his castles to another, invariably accompanied by his pet swans and pet bears. An insatiable collector of beautiful things and an unrivaled spendthrift, unstinting with artists whose work he admired, and always eager to have his portrait painted by them, he was--for all his faults--wise enough to prefer to live on in the eyes of posterity not as one ruler of a petty realm amongst many such rulers, but as a generous patron of the arts at whose court the good things of life were enjoyed to the full.

It was for him that Pol de Limbourg and his brothers painted about 1416 the incomparably beautiful miniatures known as the Très Riches Heures, now at Chantilly. Views of Paris figure in the background of several scenes contained in this Book of Hours, notably the exquisite illustration of the month of June in the Calendar. Here we see the tip of the Ile de la Cité with, on the right, the Sainte-Chapelle emerging from beyond crenelated walls "like a gigantic reliquary" (Marcel Poète) and symbolizing that successful union of the holy and the worldly life realized by St Louis. This view was made from about where the presentday Mint stands.

Another scene from the Calendar (month of October) shows peasants plowing and sowing in the shadow of the Louvre. So it must have appeared in the heyday of Charles V, when the king, abandoning the Palace where ghostly memories of the recent murders perpetrated there by Etienne Marcel and his cohorts gave him no peace, took up his residence at the Louvre, a magnificent chaos of battlemented towers, pointed turrets and steeply pitched roofs covered with sheet lead or glazed tiles, and topped with tall weather-vanes, finials, gables and so on.

FROM REALISM TO IMPRESSIONISM

NOTHING is more striking in the history of art--and indeed the history of culture in general--than the sudden breaks of continuity which take place when after a slow, sedate advance "from precedent to precedent" a more adventurous generation comes to the fore, eager for new worlds to conquer. In the case of art these bloodless revolutions are often the work of a quite small group of rebels or even a single man in whom the smoldering unrest of several generations burst into flame.

At first sight, for contemporaries, it seems as if the entire past has been done away with, ruthlessly and irrevocably: the artists' feeling for plastic values, their way of seeing, their sense of color. Then gradually, once the initial shock has worn off, the new discoveries fall into place, time irons out asperities, and what once looked startling comes to seem normal and familiar.

Painting with a set subject, a heritage of the Renaissance, had long held the field; even Delacroix when he invented a "psychology of color" thought best to keep to it. But once the romantics and realists had turned their back on an art whose painterly aspirations were so often cramped by the need for story-telling, every vanguard artist sought primarily to achieve a personal method of expression in which he could exploit the properties of his medium to the utmost.

Hence the change-over from Realism to Impressionism; the end of academic "finish" and the curriculum of the art-schools. The new men sought not merely to retain the freshness of the Sketch but made it their chief objective; rapid execution, peinture claire and an alert sensibility were the order of the day.

"You are a shining exception in the decrepitude that has come upon your art," Baudelaire wrote to Manet on May 11, 1865, à propos of Olympia which had just been exhibited and had come in for a violently hostile reception. What did our great French poet, ardent champion though he was of the "new painting," mean by the reference to decrepitude? He had in mind the decline of atelier training--that is to say of groups of young men studying art together under a common master--and the end of the age-old tradition of the apprentice craftsman.

It is certain that the teaching of the plastic arts was then at a low ebb and the masters at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (many of whom did not even really understand the classical art they made so much of) usually bestowed their favors on pupils devoid of personality who kept discreetly to the beaten track.

Forward-looking painters were now "lone wolves," resentful of discipline and no longer willing to pander to the sentimental tastes of the public of the day. Each claimed an absolute liberty to follow his own bent, the result being "a division of labor" and "a dispersal of endeavor". Ever more isolated, the artist felt free to invent his own language and under the influence of Corot to paint in bright, luminous colors, at a far remove from Courbet's sedulously lowered tones, Daumier's chiaroscuro and The shadowy forest interiors of Barbizon.

Thus it was that after the somber Footbridge to the Ile Saint-Louis (1854) and Pont Notre-Dame (1862) now in the Louvre Jongkind, greatly daring, bathed his Notre-Dame from the Quays in richly glowing light. In it we have a view of Paris seen from the Quai de La Tournelle on the Left Bank, with the archbishop's gardens to the tip of which, facing prow-wise up the Seine, the Morgue had been recently transferred.

This remarkable picture heralded the dawn of modernism, the new art that was to triumph in the second half of the 19th century. At the time Jongkind, "a blond giant with Delft-blue eyes" , had found a guardian angel in the person of Madame Fesser, a mustached matron, wife of a pastry-cook, who kept A stern check on his propensities for drinking and womanizing.

Source: Paris in the Past

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.