|

|

Finland: Cultural Zones, Structure and Relief

By Ellsworth Huntington, Samuel Van Valkenburg

Cultural Zones. --Finland's southwest coast is included in Europe A, but within the country it also shows a transition from A to C as one goes from south and west to east and northeast. Several factors are responsible for this transition--a more severe continental climate as one goes northeastward, poorer soil, less contact with the imported Swedish culture which did not extend far inland. The transition can be seen on many maps in the well-known and beautiful Atlas de Finlande, in which maps and diagrams give complete information as to Finnish geography and culture. For instance, illiteracy, almost absent in the southwest, increases eastwards until it reaches 25 per cent near Ladoga Lake, while in contrast the bank savings decrease in the same direction from over six hundred to less than one hundred "finmarks" per inhabitant. Another factor will be brought out in the discussion of land utilization later on.

How far these differences depend on Finland's racial and historical background cannot easily be determined. The Finns are probably of Asiatio (Mongolian) origin, and the small groups of Finns along the Volga may be considered a southern remnant of their westward migration. The Asiatic background of the Finns is still recognizable in their high cephalic index, broad figures, short stature, and relatively white rather than rosy skins as compared with the Swedes. Both Finns and Swedes are very blond, but the differences are so great that anthropologists are inclined to recognize a fair East Baltic race which is distinct from the blond Nordics. There has been much intermixture, however, and many of the Finns are almost Nordic in their appearance.

Early in the Middle Ages the Swedes settled in southwestern Finland along the coasts of the Bothnian Gulf and the Gulf of Finland. Their influence, helped by long political control, has been a major factor in Finland's cultural development. The Finno-Swedish culture which thus evolved was strong enough to uphold itself during the centuries of Russian rule. Hence Finland had in itself the elements for making a stable, independent state after the World War. Nevertheless, it is still a country of two racial and linguistic groups. Today, however, in contrast to the former Finnish state, the Finns have taken over the leadership, and the Swedish group (11 per cent of the population), although still the most prominent in culture and science, is perhaps destined to be submerged in the Finnish majority. Many of them say that the final aim should be one country, one people, and one language. In the Åland Islands, however, which were taken by Russia from Sweden in 1809 and kept by Finland after the World War, the Swedes are protected by special rights and will perhaps continue to maintain their separate existence.

Eastward and northward from the southwestern corner of Finland there is a more or less steady change in the racial composition of the Finnish population as appears in the following cephalic indices taken from Van Cleef Finland, the Republic Farthest North:

FROM WEST TO EAST FROM SOUTH TO NORTH

The Carelians of this table, and especially the Lapps, are generally described as much less efficient than the true Finns or Russians who live near them. The Savolatians are probably much mixed with the South Carelians, as are the North Ostrobothnians with the Lapps.

Thus the cultural decline from southwest to northeast is accompanied by a change in race. The geographic environment, however, also becomes worse because of both poorer soil and a more continental or boreal climate.

Structure and Relief. --From a geological point of view, the whole Finnish area belongs to the Baltic block of granite, gneiss, and crystalline schist. During the Ice Age, the glaciers that moved from the northwest covered this region with a thick icesheet, and glacial erosion effectively removed the soil and left the rock bare and polished. During its retreat, the glacier stood for a long time in southern Finland where a double moraine, the Salpau Selka, was deposited in front of it and still forms a prominent characteristic of the landscape. This, as has been mentioned in the discussion of Sweden, is a continuation of the moraine system that crosses the southern part of Svealand. After the final retreat, Finland was for the greater part covered by the waters of the different stages of the Baltic Sea, but as in Sweden, constant rising brought the land above the water and gave to Finland its present shape, with the numerous islands offshore marking the continuation of the glacial relief.

Since the uplift was less marked in the south than in the center where it averaged about seven hundred feet, the drainage of the greater part of the country is to the south, with insignificant divides called selkas setting apart the smaller drainage systems tributary to the Bothnian Gulf and the White Sea. The central drainage system was blocked by the double terminal moraine and many minor glacial deposits, and the water was stored in lakes. The glaciated surface, however, was already full of depressions due to differences in the resistance of the rocks, to fault lines, and to former river systems, and thus was already predisposed to the formation of lakes. The result of all these conditions has been to create an enormous number of lakes. Just about one eighth of all Finland consists of lakes. According to one estimate the number of lakes south of Lapland exceeds 35,000; another estimate gives a total of 104,000 counting all the ponds.

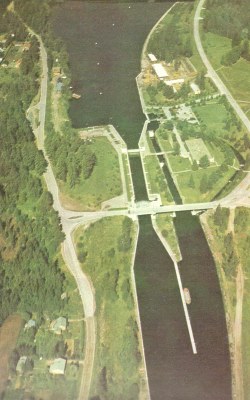

Three main lake systems can be recognized, each with an outlet through the Salpau Selka: the Saima system in the east, drained by the Vuoksen River into Lake Ladoga; the Päijänne system in the central part with the Kymen River flowing to the Gulf of Finland at Kotka; and the Näsi Järvi system in the west draining by way of the Kumo River to the Bothnian Gulf. Because the Neva River, outlet of Lake Ladoga, is in Russia, the Imatra Canal was built to connect the Saima system directly with the Gulf of Finland. The three main centers of Finnish waterpower, the base of manufacturing industries, correspond with these three outlets; the power plant of the Imatra waterfall where the Vuoksen breaks through the Salpau Selka is here the most important.

In the far north Finnish Lapland is a continuation of the Scandinavian anticline, low but somewhat more elevated than the rest of Finland, and with the main rivers flowing southward. The great Lake Enare in the north drains into the Arctic Ocean. The narrow corridor of Finland extending to the Arctic Coast at Petsamo Fiord is of importance because that harbor remains open the whole year round, protected from freezing in winter by the warm Atlantic Drift. Its potentialities have not yet been exploited, but there is already a highway to the north and a railroad is projected.

Regions and Resources. --Regions that contain Finland's coastal regions where soils, deposited by the former expansion of the Baltic Sea, cover most of the rocks. The separation of the coast into two parts is based not only on location, one being along the Gulf of Finland, the other along the Bothnian Gulf, but mainly on latitude. The Bothnian coastal region, especially in its northern section, has a much longer and darker winter and consequently a much shorter growing season than the south or Helsinki coast.

Taking these two regions together, they represent most of productive Finland. Here are the oats, rye, barley, potatoes, and fodder crops, and the large meadows used for cattle grazing and hay (A109); here are the most productive forests, from which it is easy to float logs down the rivers towards the towns on the coast; here are most of the factories which are mainly sawmills, pulpmills, paper factories, and cellulose plants which make use of forest products. These same regions contain most of the cattle, especially the dairy cattle, and here are the larger cities aside from Tammerfors or Tampere, the Finnish textile center in central Finland. And finally here along the coast are the fishing towns and villages, catching the Baltic herring, and also the trading centers which connect Finland with the outside world.

The products of the forest and dairy form the two major groups of Finnish exports. They offset imports of grains, raw textiles, and general manufactures. Of these two, forest products alone account for almost three fourths of the exports in the form of boards and battens, veneers, wood pulp, paper, and matches, paper being sold in considerable quantities to the United States. The exports of butter and cheese, as well as eggs, go mainly to Germany. As in other Nordic countries, co-operative societies are very important, especially in the export of dairy products, of which 85 per cent are handled in this way.

Source: Europe

|

|||||

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.