|

|

African Wildlife

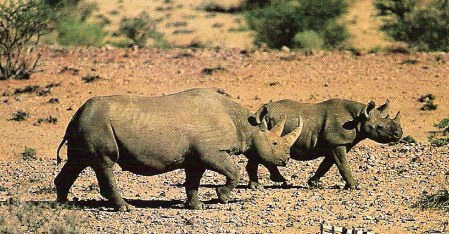

Rhino step back from extinction

The continent's white rhino population continues to rise and now totals about 7,500

Namibia's black desert rhino are safe-for now. In July 1989, a few months prior to the country's independence from South Africa, we rported that the last 400 desert rhino in the world were threatened with extinction from poaching.

Instead, thanks to monitoring and security measures, not only have Namibia's rhino been saved, but their numbers have increased to 700. According to Blythe Loutit, director of fieldwork for the Save the Rhino Trust, the displacement of white government officials and army officers after independence actually decreased the number of poaching incidents. Not exactly what we predicted.

"The real problem now is the influx of Chinese into the country," says Loutit. "They use rhino horns for medicinal purposes, so it's no secret that they're moving in, intent on setting up poaching systems across the country."

A single horn can fetch as much as $30,000 on the everthriving black market, which supplies rhino products throughout Asia.

Under the aegis of the Save the Rhino Trust, and with financial sponsorship from private organizations worldwide, local Namibians have so far succeeded in deterring would-be poachers. Fieldworkers and game trackerssome of whom are themselves ex -po achers-constantly monitor, identify, and photo-graph the rhino. They also teach locals how to generate income without killing them.

Despite success stories like Namibia's, the black rhino remains under threat: There are currently about 2,400 left in Africa, down from 3,400 in 1991. The continent's white rhino population, on the other hand, continues to rise and now totals about 7,500. Many southern African conservationists believe that the long-term solution to the rhino's plight is farming. At next month's Convention on Trade in Endangered Species conference in Harare, they will push to legalize trade in white rhino products, claiming that the white rhino are perfect candidates for farming. They are more numerous than black rhino and, if farmed responsibly, can safely grow back their horns in three years. Customers in Asia would be satisfied, they say, and local farmers would earn enough money to continue buying land for rhino cultivation.

"As silly as the rhino look without their horns, farming may be the best way to save them," says Loutit, who also believes that further research is necessary to determine the long-term effects of rhino farming.

Source: Conde Nast Traveler

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.