|

|

St. Vincent: modern outlook, antique style

By Michael Defreitas

GAZING OUT THE WINDOW of the turboprop plane as it descended over St. Vincent, I remembered the pilot's announcement during my first landing on the island:

"Ladies and gentlemen, we will have to circle around and make another approach, apparently a cow has wandered onto the runway." The airport at Arnos Vale has undergone some changes since then. It is now entirely fenced in and the main road to Kingstown, the capital, no longer crosses the runway. Although the traveler's safety has been measurably improved, I still miss the red and white bamboo poles that used to stop traffic when a plane was landing.

The nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines is comprised of 36 islands nestled in the southeast corner of the Caribbean, about 100 miles west of Barbados. The 35 smaller islands have a total land mass of just 17 square miles; the main island of St. Vincent, 1 1 miles long and 18 miles wide, covers 133 square miles. It is rugged land. Narrow coastal plains rise quickly to steep ridges that divide the main island east and west,

Michael DeFreitas is a Canadian writer and photographer who lived and taught in St. Vincent for five years. His work appears in such publications as Caribbean Travel and Life, International Living, Traveller and The Best Report. and the landscape is dominated by the 4000-foot active volcano La Soufriere. Legend holds that the island was called Hairoun--Land of the Blessed--by the original Carib inhabitants. Today it is home to 99 percent of the country's total population of 105,000.

St. Vincent's daunting geography has sheltered it from the accelerated modernization occurring elsewhere in the Caribbean, allowing it to retain its antique charm and special character. Unlike St. Vincent, many Caribbean islands are capable of handling large international aircraft which disgorge hundreds of tourists per day. These islands have histories similar to St. Vincent's, but their accessibility has led to rapid commercialization and some are now showing signs of culture shock. Lacking a major airport, St. Vincent remains off the beaten tourist track and provides a welcome escape from overcrowded beaches.

Much of St. Vincent's uniqueness stems from the unusual blend of cultures which define the island's people. Today the population is primarily a mixture of blacks, East Indians and Portuguese, but the English, French and indigenous Caribs all have left an indelible mark as well. A look back through history reveals waves of immigration and a process of conflict and assimilation that converged in the small island territory.

Written history tells us that Columbus sighted the island during his third voyage in 1498 on January 22, feast day of the Spanish patron saint, St. Vincent. He named the island without the customary landing and moved on. The first recorded landing took place much later in 1675, when a Dutch ship sank off the windward coast. The survivors, mostly slaves, were welcomed by the native Caribs. Word of this "haven" soon reached Barbados and St. Lucia, and it wasn't long before escaped slaves from those islands found their way to St. Vincent. Over time, ex-slaves and indigenous people blended into a race known as the Black Caribs. By the early 1700s, however, animosity between the Yellow ("pure") Caribs and the Black Caribs led to the territorial division of the island: Yellow in the west and Black in the east.

Although England's King Charles I assumed official ownership of the island in 1627, it was the French who established the first European colony at Barrouallie on the leeward side toward the end of the century. In 1722, George I of England gave St. Vincent and St. Lucia to the Duke of Montague, who soon after dispatched a certain Captain Braithwaite to secure a hold on St. Vincent. The expedition came ashore in the great southern bay in 1723, but met with fierce resistance from both the French and the Black Caribs and ended in failure. Instead, the French established another settlement on the eastern shore of the bay around 1740, which later became the capital city of Kingstown.

St. Vincent remained in the hands of the French and Caribs until 1762 when another English expedition took the island; the Treaty of Paris officially ceded it to the British in 1763. Despite the treaty, the Black Caribs, with help from the French, continued to fight the English. The Treaty of Versailles in 1782 ensured the French would leave the island and the British flag was officially raised in 1784; but the Black Caribs, still upset with English appropriation, continued to fight. In 1795, the great Carib chief Chatoyer was killed in battle. Left without a leader, the Caribs finally surrendered to General Abercombie in 1797.

The ever-fearful English colonists convinced Abercombie to relocate the Black Carib warriors to another English colony. As a result, by 1800 a large portion of the Black Carib population--over 5,000--were shipped to Roatan in the Bay Islands of British Honduras. The remainder were confined to the northern part of the island around Sandy Bay.

The mid-1800s saw the next significant period in St. Vincent's development, with an influx of Portuguese from Madeira. They soon controlled the shop-keeping and small trading businesses and established themselves as the true middle class. Just as significant was the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1838, which set the stage for the introduction of another race of people into the small island community. As blacks fled the island after emancipation, thousands of East Indians were brought in as indentured servants to take their places. By 1861, immigration of Hindus and Moslems was in full swing. As time passed the races became assimilated, and today's cosmopolitan population is virtually free of racial strife and color-related social tension.

St. Vincent remained under British rule until its independence in 1979. It is still part of the British Commonwealth and the present government is based on the British Westminster model. There is a parliament consisting of 19 members, one of whom holds the position of Prime Minister. The Governor General, or formal head of state, is chosen by the Prime Minister and appointed by the Queen to be her ceremonial representative.

The Right Honorable James F. Mitchell, known to friends and colleagues as "Son," is the present Prime Minister. The island boy who studied agriculture is well aware of the problems facing most of the smaller island nations today. He is a respected statesman and a leading figure in the search for a politically unified Caribbean. His recent book, Caribbean Crusade, a collection of speeches on political union and development strategies in the Caribbean, conveys the fears and optimism of many West Indians.

Mitchell writes, "Mini-states, like miniatures, are for collectors. Exquisite, but dead! ... the problems which we have are fundamentally our own, that of the small size of our resource base, and the huge appetite of our people, fed on an international culture by satellite, and without the supplies coming by satellite." According to Mitchell, any number of natural, geographic, economic and political forces can have a significant impact on the future course of a small nation. One tropical storm can wipe out an economy based largely on a single crop. Another oil crisis raising fuel and transportation costs, or even a single incident of local violence, can destroy a country's tourism industry. In addition, the islands are very dependent on North America and Europe. The countries of the industrialized world provide everything from vegetable seeds to markets for finished goods, and wield tremendous influence. The fact that most Caribbean families have relatives abroad only adds to the power of these external forces.

If St. Vincent and the Grenadines is to retain its identity, it must join forces with others with the same desires. Together they can overcome their problems and limitations through shared solutions. Under Mitchell's leadership, St. Vincent and the Grenadines continues to push for regional action as a member of both the Organization of American States (since 1980) and Caricom, the Caribbean common market which permits free trade among its members.

Mitchell's concern about the precariousness of one-crop island economies seems justified to the traveller who rides past miles of bananas growing in the foothills of St. Vincent's active volcano. The first documented eruption of La Soufriere occurred in 1718; another in 1812 was actually heard as far away as Demerera, Guyana. A third eruption in 1902 was many times more powerful than its predecessors, devastating the northern part of the island. Nine villages were levelled and two thousand people were killed. On April 13, 1979, La Soufriere exploded again, hurtling a cloud of hot ash, steam and stones thousands of feet skyward. By April 25, over twenty explosions had rocked the island. Pre-eruption rumblings had prepared most for the worst, and although 16,000 people were forced to evacuate and there was extensive damage to crops and buildings, no lives were lost.

I had been up to the volcano many times before--even swimming in the crater lake--but I had not climbed it since the 1979 eruption. This time I struggled to remain seated in the back of an old land rover as it took me through the Rabacca Farms banana estates, and eventually reached a narrow five-mile trail leading to the summit. The dense tropical forest enclosed us in a canopy of vibrant green. The trail traversed steep ridges verdant with stands of 20-foot high bamboo and a host of tropical flora. The sweet odor of the forest after the rain enveloped us as we threaded our way through the lush greenery on the lower slopes.

We were fortunate to see a number of the island's endemic birds, like the Hooded Tanager and the beautiful Purple-Throated Carib Hummingbird. Above 2,500 feet the tall vegetation gave way to a short fern-like plant the locals call "Soufriere grass." At 3,500 feet it too abruptly disappeared, revealing a moonscape of ash and volcanic gravel. When we reached the summit, a thick cloud obscured most of the crater. It finally cleared long enough for us to see a steaming island of lava rock in the center of the crater--the beautiful emerald lake I remembered swimming in had long since disappeared.

Descending from the volcano, I made my way back again through the richly cultivated fields. While menacing St. Vincent's agriculture, La Soufriere's eruptions have also yielded benefits: deep, fertile soils which make St. Vincent a tropical horn of plenty. The island's fruits and vegetables, grown on terraced slopes like those in Mesopotamia Buccament and Layou, find their way onto tables throughout the Caribbean, Europe and North America. So prolific is its agriculture that St. Vincent is locally referred to as the "Planter Isle."

The island's earth and climate, perfect for growing sugar and tobacco, attracted the first fortune seekers, who grew their crops on plantations with slave labor. This generated a need for an economical food stock, which was met when Captain Bligh returned from the Pacific aboard the H.M.S. Providence and delivered 530 breadfruit trees to the colonists. Fifty of those trees were planted in the island's Botanic Gardens, situated on 20 lush acres just outside Kingstown and are the oldest of their kind in the Western Hemisphere. Established in 1765 by Dr. George Young, the Botanic Gardens were used for propogating herbs and medicinal plants, as well as for a quarantine area for plants exported to Kew Gardens in England. A sucker from one of the original breadfruit trees still grows at the north end of the Gardens.

In addition to the large variety of rare flora and hundreds of flowering plants, the Gardens are home to a number of the island's native Amazon parrots. Natural disasters, hunting and the exotic bird trade have all decimated their numbers. Today, only 400 of these magnificent birds remain in the wild. With the help of a few international organizations, the government of St. Vincent has embarked on a captive breeding program in an effort to save their national bird from extinction.

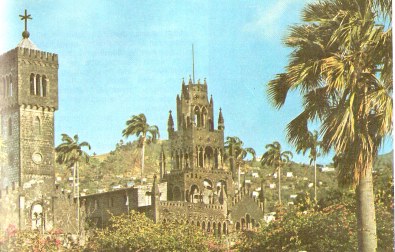

St. Vincent's natural beauty is not its only attraction. Located on the south side of the island in the remains of a long-extinct volcanic crater is the capital city of Kingstown, home to almost 25 percent of the country's population. Walking along the city's cobblestone streets, I was transported back 100 years. Grenville Street is graced with two 19th-century churches: the Georgian-style St. George's Anglican Cathedral, completed in 1820, and St. Mary's Catholic Cathedral, with its Romanesque arches and Gothic spires, completed in 1823. The Anglican church contains an interesting stained glass window entitled "The Red Angel," originally commissioned by Queen Victoria for St. Paul's Cathedral in London in memory of her grandson the Duke of Clarence and Avondale. The Queen objected to the fact that the angel was depicted in red instead of white, and ordered the window placed in storage. It was retrieved from St. Paul's basement and brought to St. George's by Bishop Jackson some years later.

These and other churches stand as silent reminders of St. Vincent's eclectic past, along with a number of impressive old forts. Standing tall over the approach to the southeast coast is the imposing form of Fort Duvernette. Despite its French name, it was fortified by the English in the late 1700s to defend Calliaqua Bay and the home of the Governor, Sir William Young. There is little doubt why the locals call Fort Duvernette "Rock Fort." It sits atop the remnants of a huge volcanic rock, about half a mile off shore. A steep stairway rises out of the sea and spirals up along the sheer sides of the 200-foot high outcrop to a battery of George III cannons. During the Carib wars, the fort was frequently attacked from shore. Most of the big guns and mortars remain trained on the land rather than the bay they were meant to protect.

This area of the coast is punctuated by white sand beaches and protected by a series of large coral reefs. Only here have the reefs produced white sand. All the other beaches in the county--including Argyle, the most popular--have ebony sand, ground fine by years of pounding surf on volcanic rock, providing stark contrast to the ivory Atlantic surf that bathes them.

The only time of year that the island is crowded and hotel rooms are scarce--there are only about 300 rooms in the entire country--is during Carnival. Traditionally a religious festival, Carnival was celebrated prior to the 40 days of Lent, the Christian period of fasting and austerity. The first celebration in St. Vincent occurred around 1920 at the Botanical Garden with local folk dances, a maypole, stick fighting and calypso singing. In 1977 the festivities shed their religious ties and were moved from February to late June, despite vociferous protests from Orthodox Catholics who feared there would be retribution for meddling with the religious calendar. They may have felt exonerated when La Soufriere began to smoke and exploded on April 13, 1979--Good Friday.

Nevertheless, the new dates remained in force, and during the 10 days between June 25 and July 6, Kingstown exults in street dancing, costumes and steelbands, a kaleidoscope of glittering colors pulsating to the beat of calypso music. More than just a splashy display, it is a time for teamwork, social commentary and political statements. Visitors say its like Rio's Carnival and New Orleans' Mardi Gras rolled into one. Vincentians prefer to think of it as "Vincey Mas."

Prime Minister Mitchell believes that one of the greatest untapped resources left in the Caribbean is tourism, but new approaches must be taken to avoid the problems other nations have experienced The key to preserving an island's identity is to develop an indigenous rather than a mass-product industry. The people of St. Vincent and the Grenadines are aware of their uniqueness and want to safeguard it. They seem to find fulfillment in the fact that they have flourished in isolation. Like their ancestors, they are curious about the "outside world" and welcome strangers to their island, but they wish to avoid "change just for the sake of change." If the tenacity of their ancestors is any indication of their determination, there is no doubt that they will.

Source: Americas

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.