|

|

New York - Transportation

A Glance at a relief map of eastern United States will show how the natural features of New York State, especially its system of waterways, determined its prime importance in the development of American transportation. The Hudson-Mohawk Valley, the only pass of low elevation through the northern Appalachians and the straightest one in the entire range, provided easy access to the Great Lakes and became the avenue of commerce between the West and the northeastern seaboard. River, turnpike, canal, railroad, motor highway, and air line traffic have all followed this route, and have made its bordering area the wealthiest, most populous, and most thoroughly industrialized section of the State. Besides this Hudson-Mohawk route, the State has the Hudson-Champlain route to Canada; the Black River route to the North Country; the Oneida route to Oswego; the Finger Lakes, approaching within portage distance of the Chemung-Susquehanna watershed and a downstream route to Chesapeake Bay; the Genesee River, cutting across from Pennsylvania to Lake Ontario; and the Allegheny route, including Chautauqua Lake, which reaches to the Mississippi. A Glance at a relief map of eastern United States will show how the natural features of New York State, especially its system of waterways, determined its prime importance in the development of American transportation. The Hudson-Mohawk Valley, the only pass of low elevation through the northern Appalachians and the straightest one in the entire range, provided easy access to the Great Lakes and became the avenue of commerce between the West and the northeastern seaboard. River, turnpike, canal, railroad, motor highway, and air line traffic have all followed this route, and have made its bordering area the wealthiest, most populous, and most thoroughly industrialized section of the State. Besides this Hudson-Mohawk route, the State has the Hudson-Champlain route to Canada; the Black River route to the North Country; the Oneida route to Oswego; the Finger Lakes, approaching within portage distance of the Chemung-Susquehanna watershed and a downstream route to Chesapeake Bay; the Genesee River, cutting across from Pennsylvania to Lake Ontario; and the Allegheny route, including Chautauqua Lake, which reaches to the Mississippi.  For the Indian, whose light canoe was easily toted between watersheds, these rivers and lakes were open paths of war and trade. High up on the slopes, where the ground was dry, thinly wooded, and free from underbrush, ran the Indian trails. The Great Central Trail crossed from Albany to Lake Erie; the Susquehanna Trail led from. Albany southwest to the Susquehanna River and into Pennsylvania; from Catskill on the Hudson a trail wound north along Catskill Creek to join one that followed Schoharie Creek to its junction with the Mohawk; another followed the course of the Genesee and crossed to the Allegheny; others led into the North Country from Lake Champlain and the upper Hudson and along the Black River.

White settlement brought relatively little improvement over routes or means of transportation for more than 150 years. Until the Revolution, settlement was largely restricted to the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys, and the rivers remained the chief arteries of travel and trade. Merchantmen loaded with goods from London and Paris sailed up the Hudson to Albany, sold their wares, and took on cargoes of pelts, ginseng, flax, and flour. Intra-valley shipments were carried by sloops; in 1749, 47 of them were plying the river. Passengers provided their own food and bedding; livestock was tethered to the mast. On the Mohawk, as the fur trade expanded and settlement crept westward beyond Schenectady, birchbark and log canoes were succeeded by clumsy, bargelike bateaux, usually poled by eight or ten men; these were in turn replaced by Durhams, broad, flatbottomed boats with sails, decked fore and aft, with capacities ranging from 15 to 20 tons.

In this same period, a crude, narrow road was cleared along the bank of the Hudson and another was built across the 17-mile sand plain between Albany and Schenectady, which was later extended to Fonda, Little Falls, and beyond. Other roads were few and of small account except locally. Wheel tracks marked the trail of British expeditions over the Lake Champlain route during the French and Indian wars. The occasional overland traveler followed a rough and tedious way, waiting for rains to cease before fording rivers and following blazed notches on trees to find shelter in the scattered homes of settlers.

Soon after the Revolution, roads were somewhat improved and extended, mainly with the proceeds of a series of lotteries in 1797. Finding its financial resources inadequate to meet the growing needs, the State chartered turnpike companies to build roads with private capital and to collect tolls to obtain a return on their investment. The Albany-Schenectady Turnpike was completed in 1805 at a cost of $10,000 a mile. Other roads were built from Schenectady to Utica, from Utica to Canandaigua, and from Canandaigua to Lake Erie. Shortly after the War of 1812 this Mohawk route was completed across the State. Its outstanding competitor was the Great Western Turnpike, running west from Albany over the ridges south of the Mohawk Valley through Cherry Valley and Cazenovia. (Today State 5 and US 20, the two most heavily traveled east-west highways in the State, follow in the main the routes of those early roads.) Turnpikes leading west from Newburgh and Catskill later became short cuts to western New York. These were the most important pikes in a highway system that by 1821 included about 4,000 miles of improved roads.

The turnpikes presented a scene of varied activity: wagoners driving six- and eight-horse teams that hauled heavily laden wagons with broadrimmed wheels; drovers herding cattle, sheep, or pigs to the eastern markets; tin peddlers in their slender wagons filled with notions; stagecoaches providing rapid transportation for travelers and mail; and emigrants moving west, their household goods packed in their covered wagons. Stage lines connected New York and Albany, and, with Albany and Troy as a hub, extended north, west, and east, joining far-flung communities. Travelers filled innumerable taverns from garret to bar; in 1815 there was on the average a tavern for every mile on the road between Albany and Cherry Valley. Since wagoners and drovers did not mix well, many taverns specialized in their clientele.

The turnpike era lasted about 30 years. The roads were never prosperous, paying small dividends at best, even in the days of heaviest travel, principally because of large maintenance costs. The competition of canals and railroads hastened the end of the private turnpike, and the roads were eventually turned over to the State.

Plans for the improvement of internal navigation were proposed by prominent men in the Colonial period, but no action was taken until after the Revolution. In the 1790's some improvements were made in the navigation of the Mohawk River, and boats of 16 tons' burden were plying between Schenectady and Seneca Lake in 1796. The demand for a transState canal came from the new settlers of the central and western parts of the State, who because of high freight rates could not profitably sell their surplus produce in the East, and from commercial men in the East who were eager to exploit the growing western market. A survey was made in 1808, and a commission explored the most likely routes in 1810, when De Witt Clinton gave his support to the proposal. The War of 1812 caused further delay, but a final survey was made in 1816 and construction of the Erie Canal was begun on July 4, 1817. The limitations of engineering skill made it necessary to build an artificial channel from the Lakes to the Hudson, rather than to attempt to canalize large bodies of water like the Mohawk. The original plan to run the canal to Lake Ontario was defeated by De Witt Clinton, who feared that trade' might be diverted to the St.Lawrence and Montreal. The inland route to Lake Erie was adopted; and Buffalo was chosen as the western terminus.

In 1825 the 363-mile 'ditch' was completed at a total cost of more than $7,000,000. On October 26 a fleet of boats left Buffalo on the canal, and cannon relayed the announcement of the event across the State in 81 minutes. The first boat, the Seneca Chief, drawn by four gray horses, carried De Witt Clinton and his party. Another, called Noah's Ark, had on board 'a bear, two eagles, two fawns, with a variety of other animals, and birds, together with several fish—not forgetting two Indian boys, in the dress of their nation—all products of the West.' The fleet was welcomed at every stop by enthusiastic crowds, and an astonishing number of toasts were drunk. Green-eyed Philadelphia called the celebration a 'Roman Holiday.'

On November 4, in a solemn ceremony, Clinton poured a keg of Lake Erie water into New York Bay, and the 'Marriage of the Waters' was consummated. The Champlain Canal was completed two years before the Erie.

At first passenger traffic on the canal was greater than freight traffic, but by the end of the first decade of operation the freight tonnage passing West Troy had increased fivefold and the canal was definitely a success. The desire to provide the advantages of water transportation to every part of the State led to the construction of more than 10 branch canals, the most important of which were the Oswego, the Cayuga and Seneca, the Chemung, the Black River, and the Genesee Valley Canals. The first enlargement of the Erie was begun 10 years after its completion. Tolls on the Erie, abolished in 1882, more than covered the cost of its enlargements up to that date and the deficits of the other canals.

By building this canal system, the State interconnected its waterways and provided a tremendous stimulus to settlement and the development of agriculture, commerce, and industry through the drastic reduction in freight rates and the improved accessibility of markets and supplies. Like a great system of arteries, the canals carried a golden stream of commerce across the State and up and down the Hudson, bringing new wealth and life to every section of the State. At canal termini, and at strategic points where agricultural products were processed and freight had to be unloaded and reloaded, towns grew rapidly into business and financial centers and markets for local products. Branch canals brought Pennsylvania coal to the cities, supplying the fuel for the development of modern industry. New York City, export and import center for the entire system, became the Nation's commercial metropolis. Moreover, the canal, together with the short-line western railroads, gave growing States like Illinois, Indiana, and Minnesota access to the markets of the East, and thus linked their interests more firmly with those of the North in the Civil War crisis than would have been the case had the bulk of their products gone to market by way of the Mississippi.

In this same period, beginning in 1807 with the success of Fulton's Clermont on the Hudson, the steamboat became an important means of transportation on waters within the State and on its borders. The steampowered lake ship strengthened Buffalo's position as the eastern terminal for the Lakes trade, and the ocean-going steamship made New York City the major world port of the Nation.

A year after the Erie Canal was opened for commerce, the first railroad in the State, the Mohawk & Hudson, was chartered. It began running between Albany and Schenectady in 1831. The rails were of wood, faced with strap iron and secured to granite blocks. The first locomotive, the De Witt Clinton, built in New York City, hauled a train of stagecoaches mounted on special trucks. Riding was accompanied by jerking and jolting, and the clothes of outside passengers sometimes caught fire from the pine embers blown from the smokestack. But improvements were rapidly introduced and the road was declared a success. In 1832 it established connections with the Schenectady & Saratoga Railroad, which opened that year as a horsecar line. In 1835 the Rensselaer & Saratoga Railroad was built between Troy and Ballston Spa, where it connected with the Schenectady & Saratoga.

In the early days of their development railroads were thought of as auxiliary to waterways, providing short cuts and feeders. As they grew in wealth and popularity and roads were planned to parallel the Erie Canal, the State imposed restrictions to protect its canal investments, especially in regard to the transportation of freight. Not until 1851 were all railroads allowed to carry freight at their own rates and retain the revenue. Thereafter began the competition which led to abandonment of some of the branch canals and greatly reduced the importance of the Erie.

In the thirties a number of short lines, varying in gauge, were built across the State: the Utica & Schenectady in 1836; the Syracuse & Utica in 1839; the Auburn & Syracuse in the same year; the Auburn & Rochester in 1841; the Tonawanda between Rochester and Batavia in 1837, extended in 1842 to Attica; and, in the latter year, the Attica & Buffalo. Thus eight short lines extended disjointedly between Albany and Buffalo. Trans-State travel had its difficulties, especially the several changes of cars and the uncertainty. of schedules. In 1853 these roads, together with several branches, were consolidated to form the New York Central. North from New York City, the New York & Harlem, begun in 1832, crept gradually up through the easternmost counties, reaching Greenbush (Rens, selaer), opposite Albany, in 1852. But it was beaten to this terminus by the Hudson River Railroad, constructed along the edge of the river. Cornelius Vanderbilt, prominent steamboat operator, acquired control of both roads between Albany and the metropolis, and then forced the New York Central to capitulate to him by refusing to furnish connections at Albany. The consolidated roads, headed by Vanderbilt, became the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad, and later, after reorganization, simply the New York Central. In 1871 the New York Central, which controlled—and still controls—the only right-of-way entering Manhattan from the north, built the first Grand Central Station at 42nd Street.

The railroads in general intensified and accelerated the economic processes stimulated by the canals. In sections of the State where the influence of the canals was limited, as in the Southern Tier and the North Country, the railroads supplied the primary impulse for development. The Eric Railroad provided the Southern Tier with an outlet to the eastern seaboard. Even before it was completed in 1851, between Piermont on the Hudson and Dunkirk on Lake Eric, the Erie began its checkered career. After many difficulties, caused in part by provisions in its charter, it was granted new termini—Buffalo in the west, which enabled it to compete with the New York Central for traffic, and Jersey City in the east, which brought it within the metropolitan district. Its track gauge was six feet, and 50 years passed before it adopted the standard gauge of four feet, eight-and-one-half inches. Overcapitalization and waste drove the road to Wall Street for aid, and it was turned into a financial football by Daniel Drew, James Fisk, and Jay Gould, at the expense of Vanderbilt, whom Gould outmatched in manipulation. The history of the Erie has been a succession of receiverships. Income from its immense freight traffic has failed repeatedly to overcome the effects of the financial maladministration that dogged it from the start.

The first line in the North Country, the Northern Railroad, completed in 1850 between Lake Champlain and Ogdensburg, was built by Boston interests to participate in the commerce with the Great Lakes area. The road is now a branch of the Rutland Railroad. Another important North Country road was the Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburgh (sic), formed in 1861 by a merger of two earlier roads. When it extended its lines and began to compete with the New York Central, it was absorbed by the latter. After a severe rate war the West Shore Railroad, built along the west shore of the Hudson and the south shore of the Mohawk and west to Buffaloclosely paralleling the Central throughout, suffered the same fate. The Albany & Susquehanna (now part of the Delaware & Hudson), together with its, branches, and the Ulster & Delaware, joining Oneonta and Kingston, carried Pennsylvania anthracite to the industries of eastern New York and northern New England. In all, ten railway systems at present operate 8,260 miles of track in the State.

Men of New York have played a large part in the development of railroading since the time when scouts went out on horseback to locate late trains and brakemen stopped trains by the exertion of sheer physical strength. The first train order sent by telegraph is credited to Charles Minot, superintendent of the Erie. Henry Wells, of Albany and points west, and William Fargo, of Pompey, Buffalo, and points west, organized some of the earliest express companies. George Westinghouse, inventor of the air brake, was born in Central Bridge. The first sleeping cars were built in the late fifties almost simultaneously by Theodore Woodruff, of Watertown, and Webster Wagner, ticket agent at Palatine Bridge. In 1867 Wagner built the first drawing-room coach, or palace car, befrilled with plush seats, carved cupids, and crystal chandeliers; and in 1890 his company was merged with the Pullman Company to form the Pullman Palace Car Company. Within the last few years the Delaware & Hudson Railroad has developed in its Watervliet shops the 'velvet rail'—jointless, welded track a signal block in length, which reduces maintenance costs and eliminates the clickety-click of rail joints.

Another phase of railway transportation is represented by the streetcar, at first drawn by horses, later driven by electricity carried in wires strung overhead or laid in a channel between the rails. After the turn of the century this new public utility, widely applied, enabled the cities of the State to spread out in residential and industrial suburbs. A natural extension of the urban streetcar was the interurban trolley connecting upstate cities, in some cases paralleling the railroads, in other cases providing more direct connections than the railroads afforded. Some operators built picnic grounds and amusement parks at countryside terminals and encouraged week-end outings. Equally popular was the 'Twilight Trolley Tour,' for which cars decorated with colored lights were provided to rattle lovesick spooners' over 25-mile networks of trolley lines. But the introduction of the bus marked the beginning of the end for the trolley. The interurban lines have almost all been superseded, and within cities streetcar lines are being replaced by bus lines. Some of the old trolley cars have been saved from destruction by conversion into lunch wagons, and, thus transformed, stand stationary and disconsolate beside the roads they once traversed.

A bicycle craze that set in early in the trolley period led to the formation of cycling clubs, which built and maintained hundreds of miles of cinder paths out of the annual SI fees paid by members. Their hard smoothness conducive to high speed, these paths produced the 'scorcher,' forerunner of the present-day automobile driver who has nowhere in particular to go but is in a terrible hurry to get there. Many of the old bicycle paths were widened to accommodate the first 'gas buggies,' 'steamers,' and 'electrics.'

In recent years, the large-scale use of the automobile—in 1939,2,749,135 motor vehicles were registered in the State—brought to the fore the problems of a new age in transportation. The turnpike era was in a sense revived, in an extremely elaborated and accelerated—one is tempted to say a 'jazzed-up'—form. The highway became a motorway, subject to traffic that was dense and continuous, traveled by vehicles that were ponderous, vehicles that were swift, and vehicles that combined something of both qualities. The science of highway engineering had to be revised and relearned, and the licensing and regulation of motor vehicles and, in large part, road construction and maintenance became functions of the State. From 1922 to the end of 1935 the State appropriated $568,000,000 for its highways, in addition to Federal and emergency grants of $128,000,000. But continued increase in traffic and speed demanded continued additions and improvements. A-five-year plan, adopted in 1936, called for the reconstruction of 5,230 miles of State and Federal routes that did not meet the needs of modern traffic, to include 1,617 miles of three-lane and 929 miles of four-lane pavement.

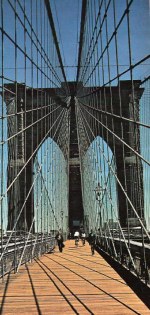

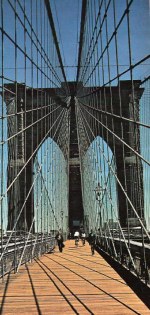

Expansion of the highway system involved the construction of a number of noteworthy bridges, including the George Washington Memorial, Bear Motintain, and Rip Van Winkle Bridges over the Hudson the Thousand Islands Bridge over the St.Lawrence, the Champlain Bridge at Crown Point, and the Peace Bridge at Buffalo. Westchester County has developed a system of three-'and four-lane boulevards through landscaped parkways leading into New York City, and the State has built extensions of these north toward Albany and cast toward New England. Similar developments have been carried out on Long Island. In the field of highway illumination the General Electric Company has introduced sodium vapor lights, which are now used along stretches' of road in various parts of the State.

The private motorcar, the motor bus, and the motor truck have made serious inroads on railroad traffic. The railroads have in part solved the problem of the motor bus by gaining control of the largest company in the State; but the general problem of the railroad in a motor age is national in scope and waits to be dealt with as such.

Aside from the pre-eminence of New York City in transatlantic and coastal commerce, water transportation has remained a significant factor in the State's economic pattern. In 1918 the modernization and enlargement'of the old canal system was completed to form the Barge Canal, which accommodates boats of. more than 2,000 tons' capacity. West to Rome the old Erie was abandoned and the Mohawk River canalized; beyond, the new canal follows the route, though not always the bed, of the old, with short branches to Syracuse and Rochester. The Champlain Canal division of the new system utilizes the canalized Hudson north almost to Fort Edward and thence extends in a new channel to Whitehall. The remaining units of the Barge Canal, outside of feeders, are the Oswego and the Cayuga and Seneca Canals; other divisions of the original system have been abandoned. Great advances have been made in canal craft. Numerous barges are towed by a single tug, and Diesel-electric boats with shallow hulls and disappearing Stacks now carry cargoes between the most remote Lake ports and New York without transshipment. In 1939 the total canal tonnage was 4,689,037, principally petroleum products. Since 1932 ocean-going steamers come up the Hudson to the Port of Albany, transporting petroleum, lumber, pulpwood, wheat, and molasses. In and out of the Great Lakes harbors— Buffalo, Rochester, Oswego—lake carriers transport coal, grain, pig iron, limestone, and automobiles.

It was a citizen of New York State, Glenn Curtis, who emerged as the foremost rival of the Wrights in the early days of the airplane. At Hammondsport, on Keuka Lake, Curtiss developed a plane that was a definite improvement on the Wright ship of the time. Though the Wrights, who were first to fly, sued Curtiss for infringement, they added wheels—a Curtiss innovation—to their landing gear; and the rivals finally settled down to work in peace. Curtiss made the first public airplane flight of more than a mile in the United States, was first to fly a plane from Albany to New York City, and among other feats, pioneered in developing hydroairplanes, flying boats, and military combat planes.

The effect of the airplane on transportation in the State is still largely undefined. American Airlines maintains regular schedules in the principal cities, and the Federal Bureau of Air Commerce has constructed five completely equipped emergency landing fields at strategic points along main routes. The routes from Albany to New York City and Buffalo are lighted by the Federal' Government; the others in the State, except between Albany and Montrealy, are commercially lighted. Radio beams on all the routes direct pilots flying blind. As part of the Government's emergency work programs, many millions of dollars have been expended on airport construction and improvement. In 1938, 97 airports and landing fields in the State were recognized by the Bureau of Air Commerce.

|