|

|

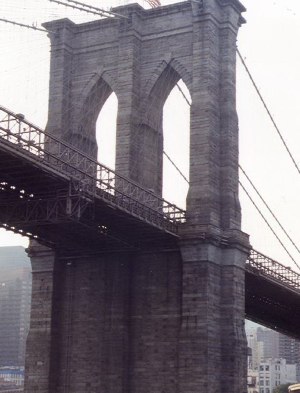

New York - New York City - Brooklyn Bridge

Brooklyn Bridge, soaring over the East River, is the subject of more paintings, etchings, photographs, writings, and conversations than any other suspension bridge in the world. Uniting the maze of the nineteenthcentury brick and frame residences, factories, and warehouses of the Brooklyn shore and the modern skyscraper district of lower Manhattan, the majestic highway has supplied an extravagant theme to romantic and symbolic fancies. Native artists, including the noted water-colorist John Marin and the abstractionist Joseph Stella, have played many variations upon its graceful catenaries, suspenders, and granite towers; while the poet Hart Crane conceived it in his The Bridge as the dynamic emblem of America's westward march. Brooklyn Bridge, soaring over the East River, is the subject of more paintings, etchings, photographs, writings, and conversations than any other suspension bridge in the world. Uniting the maze of the nineteenthcentury brick and frame residences, factories, and warehouses of the Brooklyn shore and the modern skyscraper district of lower Manhattan, the majestic highway has supplied an extravagant theme to romantic and symbolic fancies. Native artists, including the noted water-colorist John Marin and the abstractionist Joseph Stella, have played many variations upon its graceful catenaries, suspenders, and granite towers; while the poet Hart Crane conceived it in his The Bridge as the dynamic emblem of America's westward march. During more than half a century of continuous use, the bridge has retained its place as the most picturesque of the sixty-one spans that bind Greater New York into a world metropolis. It was designed in 1867 by John A. Roebling, who had built the bridge at Niagara Falls and the more remarkable one over the Ohio River at Cincinnati. While engaged in drawing the plans for Brooklyn Bridge, Roebling sustained an injury which resulted in his death from tetanus a year before construction began. His son, Washington A. Roebling, became construction engineer, but he too was injured. From a window of a Brooklyn Heights residence he supervised the construction of the bridge, watching its progress through a telescope.

The bridge was opened to traffic on May 24, 1883, pedestrians being charged a toll of one cent. Six days later a tragedy occurred on the crowded walk. A woman fell down the wooden steps at the Manhattan approach to the promenade, and her screams resulted in a panic in which twelve persons lost their lives and scores were injured.

Unlike the steel towers of the East River bridges that followed, the buttressed towers of this bridge, rising 272 feet above mean high water, are constructed entirely of granite. Expressing the increasing load, they, become thicker as they extend downward; and the segmental arches that tie the piers together are buttressed against lateral thrust. The whole design is a superbly clear statement of the contrast between the ponderous compression in the towers and the tight-strung tension of the steel members.

The roadway platform, eighty-six feet in width, is hung on two-inch diameter steel suspenders strung from two pairs of cables -- the catenaries -sixteen inches in diameter. Each cable is composed of 5,296 galvanized steel wires. (The total length of wire used is 14,357 miles, a distance more than half the circumference of the earth.) Each is capable of sustaining a live load of 2,000 tons, or a total live load equal to 48,000 tons, the weight of the structural steel in the Empire State Building.

The bridge has an over-all length of 6,016 feet, and the center of the 1,595.5-foot channel span is 133 feet above the river at mean high water. Until the Williamsburg Bridge was completed in 1903, with an over-all length of 7,308 feet, Brooklyn Bridge was the world's longest suspension span.

Among the ingenious methods introduced by the younger Roebling in the construction of the bridge -- methods which have since exerted considerable influence on engineering technic -- were the pulley-and-reel system for spinning the cables of the catenaries, the use of semi-flexible saddles as cable rests to provide for expansion and contraction owing to temperature changes, the employment of chains of eyebars in the anchorages and wire wrapping as protective covering for the finished cables, and the cross-lacing of suspenders with stay cables that act as bracers.

The center promenade, a board footwalk twelve feet above the floor of the bridge, is flanked on each side by elevated tracks and one-way, doublelane driveways, which accommodate both trolley and vehicular traffic. The Manhattan approach to the footwalk slopes upward from the damp, gloomy Park Row floor of the BMT terminal opposite City Hall Park. In this dark and rather vague spread, where the streetcar lines crossing the bridge curve into their terminals, are news venders, frankfurter stands, and iron gates, usually closed, leading to the elevated lines overhead. This almost subterranean atmosphere is also characteristic of the Brooklyn approach, which is graded to the Sands Street level of the sprawling BMT terminal structure.

In the Manhattan abutment are wine vaults, suggestive of Roman catacombs. Built in 1876, seven years before the bridge was opened, they were used until recently by a New York department store as a storage place for European liquors. The cellars, entered from 209 William Street, were sealed during Prohibition.

The bridge quickly became popular as a Sunday promenade. Here strolled women in Sunday ruffles, hourglass stays, bustles fringed with everything but bells, and shoes laced up to the kneecap; gentlemen trussed in broadcloth to the Adam's apple, inquisition collars to the ears, and trousers to the toes. Foot traffic gradually waned, however, with the installation of surface cars on the bridge and with the building of the larger Williamsburg, Manhattan, and Queensboro bridges. The elevated line began operating over the bridge in September, 1883, the surface cars in 1898. The present workday traffic averages about twenty-six thousand vehicles.

The bridge affords a magnificent view of the East River, the harbor, and downtown Manhattan -- the buildings of the financial district changing their hues during the different hours of the day. Down below, seen from the Manhattan grade, lies the darkness of the old city -- markets and gloomy warehouses to the south; and on the north, slums, elevated lines, and crooked streets, where one notices horse-drawn vehicles and an old mission with JESUS SAVES painted on the walls in large white blocklettering. Knickerbocker Village, a housing development, is set among these slums spreading north from the foot of the bridge.

The apocrypha of Steve Brodie belong among the bridge's more distinctive legends. There are men living who claim they saw Brodie's leap from the bridge in July, 1886, the rescue skiff tossing on the East River, the hero-worshipers who cheered as he climbed to the dock; on the other hand, mention of his name causes many old-time barkeepers to put their tongues in their cheeks. In any event, Brodie has entered the American idiom: to "pull" or "do a Brodie" has come to serve as a synonym for taking a high dive, whether on the stock market, in a love affair, or in the prize ring.

The promenade still draws its visitors, lyrical, noisy, or inarticulate. In the famous "view" of the bay and sky line, tourists encounter the original of a long-familiar picture post-card panorama; while the high arched towers and vast curving cables of the bridge itself are rediscovered daily by amateur camera artists. On summer days old ladies, invalids, Sunday morning strollers, unemployed men, and wandering boys and girls absorb here the indolence of space, sun, and water. Employees of downtown office buildings seek at the bridge during lunch time and after work a session with the outer world. At twilight, the conventional beauty of the setting attains such intensity that even the wisecracks of up-to-date lovers are sublimated. And in the wastes of night, so passionate is the contrast between the altitude of the passage itself, that the solitary pedestrian feels himself drawn into association with all the extravagances of the poets.

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.