|

|

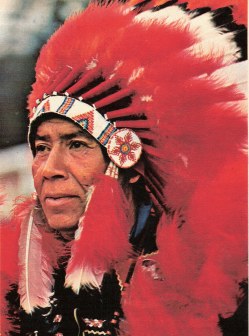

New York - Archeology and Indians

Archeologists are eagerly searching for evidence of the first inhabitants of what is now New York State—presumably remote descendants of the Asiatic-Mongoloid wanderers who migrated to America across Bering Strait. These earliest inhabitants were possibly people of the widespread Algonquian linguistic stock, who appear to have come to the area by way. of the Niagara Peninsula. They belong to what archeologists term the Lamoka Focus, and exhibit traces of a long established culture. Projectile points are long and narrow with a straight stem or faint side notches; no traces of pottery exist; and the absence of certain other implements suggests that these Archaic people were nomadic hunters rather than settled farmers. Archeologists are eagerly searching for evidence of the first inhabitants of what is now New York State—presumably remote descendants of the Asiatic-Mongoloid wanderers who migrated to America across Bering Strait. These earliest inhabitants were possibly people of the widespread Algonquian linguistic stock, who appear to have come to the area by way. of the Niagara Peninsula. They belong to what archeologists term the Lamoka Focus, and exhibit traces of a long established culture. Projectile points are long and narrow with a straight stem or faint side notches; no traces of pottery exist; and the absence of certain other implements suggests that these Archaic people were nomadic hunters rather than settled farmers. Following them in the culture sequence thus far established by research came the Laurentian culture, the most widely disseminated in the State. It appears to have entered from the northeast through the St.Lawrence and Hudson Valleys and, like the Archaic, was produced by a hunting and fishing people. Chief among its distinctive artifacts are broad-bladed po ints of many forms, gouges, plummets, and ground slate knives.

The Vine Valley occupation, entering in two waves, probably from the west, brought a richer culture. Polished stone implements are more numerous; crude pottery and a greater variety of bone and antler tools suggest more stable settlement, leisure, and the progress of invention. This culture was also widespread.

The Hopewellian (Mound Builder) invasion, which preceded the Owasco Aspect, brought a people who often buried their dead in sizable mounds, made copper articles, ornaments, pottery, and pipes of superior quality, lived in villages, cultivated food plants and tobacco, and wove fabrics. Few traces of them have been found in eastern New York, but their handiwork unearthed in western counties exhibits an affinity with larger finds in Ohio.

The Owasco occupation was rooted to the soil and enjoyed a high degree of cultural attainment, as indicated by the superior temper, design, and ornamentation of pottery, clay smoking pipes, triangular arrowheads, and the domestication of corn and beans. The lack of intermixed European tools, utensils, or ornaments proves that this culture was definitely preColumbian, and it doubtless existed for several centuries before a.d. 1300.

The final wave of Algonquian penetration was probably that of the Lenni-Lenape. They were on the eastern seaboard of New Jersey and Pennsylvania to greet the white man, who found them banded in confederacies, tilling the soil, smoking tobacco, and inscribing rocks to denote tribal boundaries. To the white intruders these people were the Delaware, named after the river traversing the heart of their domain. The LenniLenape dominated the southeastern part of what is now New York State. Not long before the coming of the white man, the irresistible infiltration of the Iroquois had begun on the southwest, south, and north.

The variety of geographical features, the abundance of nuts, fruits, edible root, and wild game, the presence of flint, and, above all, the far-spreading system of interconnected waterways made the New York region a strategic stronghold that would endow with abundance and authority any Indian group able to win it and hold it.

Although the Algonquins equaled the Iroquois in bravery, intelligence, and physical prowess, they lacked the Iroquois genius for political organization and the Iroquois zeal for protracted warfare. The northern group of the Five Nations, who called themselves the 'Men of Men,' in the first half of the sixteenth century cut their affiliations with the Huron-Iroquois groups of Canada, slashed their way through the vigorous but futile resistance of the Algonquins, and settled along the Mohawk River; those who came from the south and west settled in the foothills south of Lake Ontario. The conflict lasted well into the early days of white settlement; the Battle of Kinguariones was fought in 1669, though a decade or two before that the mighty Iroquois had become the virtual masters of what is now New York State and had either absorbed the Algonquins or driven them out.

One source of Iroquois power was their confederation. Late in the sixteenth century, Dekanawidah, probably of Huron blood, recognized the urgent need for peaceful unity and devised a code of laws that would bring all men together as friends and brothers. Although his dream of eternal peace was soundly ridiculed by the warriors, Dekanawidah enlisted the aid of Hayonhwatha, a Mohawk by birth, and together they launched a campaign for Iroquois solidarity which they zealously promoted for five years. Hiawatha, who began his reforms among the Onondaga, combined political strategy with eloquent oratory and finally won over Adodarhoh, powerful Onondaga opponent of the plan, by offering this fiercest of warriors the position of moderator in the league council. Legend has it that this form of flattery 'combed the snakes from the head of Adodarhoh.'

About the year 1570 the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca were welded into the Five Nations Confederacy; and the first great council fire blazed high on what are now called the Pompey hills.

Although the founders of the league likened their new government to a long house where families dwell together in harmony,' the confederacy was not established without considerable jealousy; fear of supersedence and demands for special concessions were problems that had to be ironed out with a high degree of diplomacy. But the desire to control the fur supply of their neighbors to the north and west and thereby monopolize the trade in European goods finally brought about a real union; the primacy in matters of state went to the Mohawk, the Onondaga were granted custody of the permanent council fire, and the Seneca were given two war captains. These three nations together constituted the 'elder brothers'; across the fire sat the Oneida and Cayuga, 'younger brothers' of the larger nations.

The league's constitution, as it developed, consolidated a civic and social system built on the old pattern of tribal society and embracing ideas of universal peace and brotherhood, set up a policy of fraternal expansion, and provided for the appointment of the peace chiefs by the women—in effect, gave the women the right to vote.

The 'Men of Men' did not call their women squaws; to them women were 'our mothers.' Although the Iroquois woman was practically the domestic slave of her arrogant spouse, she exercised a large influence in government, shared in religious rites and festivals, arranged marriages, and authorized divorce. All tribes recognized the descent of name and property through the female line.

The Great Law, which was transmitted orally from one generation to another, proved to be a governmental system well suited to the stage of culture for which it was designed. A federal councl was established and each of the Five Nations was represented by delegates, or federal chiefs. Organization of the tribe began in the matrilineal family unit, called the owachira, of which the eldest woman was the nominal head; and two or more owachiras, believed to be related, made up a clan, which functioned within the tribe to ensure economic security and political representation for its members. Members of the clan shared certain property. The women of the clan elected its chiefs and subchiefs, who represented the clan in tribal councils. Privileges of membership included a common burial ground, the right to give childbearing women of the owaclziras the power to elect and impeach chiefs, the right to clan personal names, help in securing a mate, and protection through 'blood revenge.'

Polygamy, practiced by the Algonquin and Huron, was not encouraged by the Iroquois, although it infrequently occurred. Marriage was arranged by the mothers. The girl signified her mother's choice of a husband by placing a basket of bread at the door of the youth's home. If the lad and his mother agreed on the advisability of the matrimonial venture, they sent back a basket of food as a token of acceptance; but if the match was not acceptable, the girl's gift was returned untouched. If both sets of parents gave their consent, the simple ceremony, consisting chiefly of a lecture on the duties of social life, was performed by the clan matrons, through the chiefs or some orator as their surrogate. A pair of impetuous lovers might ignore formal routine and stage an elopement, in which. case one night away from home validated the marriage. Divorce was relatively simple, sufficient grounds being infidelity or failure to provide.

The birth of a child, male or female, was a welcome event, but female offspring were more highly valued. Most villages maintained small lodges to which women retired for childbirth; and the newborn babes were cared for in these crude maternity homes until they were ready to be shown to the family. Comparative lack of sanitary precautions, dietary deficiencies, and the rigorous climate resulted in an extremely high rate of infant mortality.

Although the Iroquois moved their habitations every 10 or 12 years, they built their villages strong for shelter and military protection. Trees were felled, peeled, and converted into pole frameworks. Elm bark was pressed flat into sheets, laid horizontally over the frames, and tied down with cords. They built homes ranging from individual bark cabins to log communal houses 200 feet long; erected stout stockades 16 to 30 feet high, with platforms on the inside wall for fighters, weapons, and water; and dug deep moats outside the barricades.

Agriculture was the chief basis of Iroquois stability. Each village had its fields and, in the 1700's, its orchards; the men cleared the land, the women planted and cultivated the fields. Corn (maize), which had been developed by deliberate breeding and was the Indian's particular grain, was planted in rows, so many kernels to the hill; and the intervals between the hills were measured by the 'long step.' These early New York farmers raised tobacco, beans, Jerusalem artichokes, and squash. Exhausting the soil and the supply of firewood in a dozen years, they moved the village to a new site.

Commerce in pre-Colonial days consisted principally of direct exchange of commodities among families and tribes. The measurements used included finger width, palm breadth, finger span, and the integral fathom, just as is the case, less directly, in England and the United States today, as indicated by the term 'foot.' Wampum, arrowheads, and beaver skins were the media of exchange.

The Indian was truly a craftsman. Combining his native patience with ingenuity, he made bone knives, serrated stone saws, and bow-operated drills; and with these tools he fashioned fighting and farming implements, made combs from antler, and built bark canoes, snowshoes, and toboggans. The women shaped clay into pottery and worked pelts into clothing.

Indian warfare, before the coming of the white man, was carried on with crude weapons: bow and arrow, tomahawk, and war club were the primary equipment for offense, and round shields and slat armor for defense. War expeditions rarely numbered 100 men and only on rare occasions did the Indians assemble a force that could be considered of army proportions. Their technique called for concealment, surprise—the swift swoop from ambush. Scalping, an aboriginal custom of the Iroquois which they probably introduced to the Northeast, was encouraged by both the French and English, who offered bounties for the dripping topknots of their enemies—white or Indian. With this stimulus the practice spread rapidly and became characteristic of Indian warfare. Cannibalism was a common practice among the Huron-Iroquois, and the New York Iroquois indulged in the practice at times, under the belief that a great warrior's heart if eaten would provide increased valor and strength.

Christianity was first brought to the Indian by thd Franciscan Order of Recollects in 1615 and later by the courageous Jesuits. The missionaries suffered every hardship; blamed for epidemics, crop failures, and grasshopper plagues, they were frequently subjected to extreme torture and killed. The Jesuit Relations abound with tales of such atrocities.

The white man's religion was all but incomprehensible to the red man. Intimate observations of nature' formed the whole fabric of his philosophy; he knew hunger, the change of the seasons, the budding of flowers. To him life was practical and understandable. He envisaged a continuous conflict between good and evil spirits and was perfectly willing to bribe either group with generous offerings. He believed that all living creatures possessed souls and that a supernatural force controlled all nature. Probably under the influence of the Jesuits, he came to believe in a land of souls, with separate villages for homicides and suicides, who were not admitted to the village of the blessed.

The Five Nations were continually at war with their neighbors, with the aim of controlling the fur trade. The Algonquin and the Huron, having suffered from these imperialistic tendencies, welcomed the arrival of the French, whose 'thunder poles' spoke death. In order to wreak vengeance upon the 'upstart' Iroquois secessionists, the Huron quickly formed an alliance with Samuel de Champlain and induced him to accompany a war party against the Mohawk. In the subsequent engagement near Ticonderoga, Champlain and his two musketeers introduced the use of firearms in Indian warfare, and the dumbfounded Mohawk were easily defeated. This tragic experience was symbolic of the enmity which the Iroquois developed toward the French and which helped defeat French colonization in the New World. Again the contest for domination of the trade in beaver pelts was the motivating factor.

War then blazed in earnest. The Five Nations struck their foes at every vulnerable spot. Town after town was captured; French priests were tortured, thousands of Huron warriors were slain; women and children suffered extreme hardship. With the fall of the great village of Scanenrat in 1648, the Huron confederacy was completely broken and its people fled to their allies, the Erie, the Neutrals, and the Andaste.

Determined to wipe out the last vestige of resistance, the Five Nations proceeded to conquer and absorb these neighboring tribes, which had previously rejected league membership. The Neutrals, neighbors of the Seneca on the west, were the next to be crushed. The Erie, occupying the southwestern corner of the present State, were battled into submission in 1654-5; and then the conquest of the Andaste in a bloody 10-year campaign completed the struggle for domination.

First tasting the bitter fruit of the white man's invasion at the hands of Champlain, the Iroquois established friendly relations with the Dutch and English; traded valuable beaver and mink pelts for flashy baubles, cotton cloth, guns, and rum; and were systematically cheated by the crafty Europeans. The Hollanders, chiefly interested in the profitable fur trade, paid little attention to the Indian's lack of Christianity, but the English recognized the great power of the Five Nations Confederacy and endeavored to convert the Iroquois into loyal allies. The Episcopal Church sent out missionaries; John Stuart translated the New Testament into several Iroquoian languages; and Sir William Johnson, highly esteemed by the Indians, personally financed the publication of the Episcopal liturgy in Mohawk. Adding flattery to religion, the British formally denounced French interference with the Five Nations, and in 1687 James II issued a warrant to Governor Dongan authorizing protection of the Iroquois as subjects of Great Britain.

Proud of their new sovereignty, the Iroquois raided French settlements on the St.Lawrence with a bloodthirsty eagerness that threatened Montreal and caused bloody retaliation by Count Frontenac's vengeful hordes in the Schenectady massacre. The subsequent devastation of Iroquois villages brought the Five Nations to their knees and resulted in a treaty with the French in 1701.

After the cessation of war with the French, the Iroquois enjoyed a long period of ascendancy. They diplomatically played off the British and French against each other, and made their own control of the fur trade more certain. The Delaware were subdued, several Pennsylvania tribes were annexed, and in 1722 the Tuscarora were admitted to the league, which thereafter became known as the Six Nations Confederacy.

Despite their smoldering hatred of the French, many Iroquois groups joined the sporadic raids made against the English by motley war parties of Algonquins and Hurons during the French and Indian War. This alienation of their allegiance was evidently caused by fear of the French, distrust of English land speculators, and the dismal failure of British military efforts. But even before the final British victory the Iroquois were won back into the British fold by Sir William Johnson, who staged a grand council at Fort Stanwix in 1768. This conclave, attended by more than 3,000 Indians, marked the end of the Cherokee Wars and created a line of territorial demarcation beginning at Fort Stanwix and extending south and west to a point north of Fort Pitt, then down the Ohio River to the mouth of the Tennessee. West of this line no white settlement was to be made. It was the subsequent violation of this boundary that caused much of the Iroquois bitterness toward the colonists.

The beginning of the Revolution found the Six Nations divided in allegiance between the English and the Continentals. The Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca remained steadfast British allies; the Oneida and Tuscarora, through the powerful influence of Samuel Kirkland, were friendly to the Colonials.

Joseph Brant, full-blooded Mohawk chief whose sister had married Sir William Johnson, joined the British forces in 1776, received a captain's commission, and played an important role throughout the Revolution. A force of Iroquois under Brant and Sayenqueraghta, supporting the British and Tories at Oriskany on August 6, 1777, was outbattled by Herkimer's makeshift militia. Smarting from this costly defeat, the Iroquois retaliated by desolating the New York and Pennsylvania frontiers. Chief Ojageght joined in Colonel Walter Butler's raids at Wyoming and Cherry Valley; Blacksnake, Little Beard, and Cornplanter left red trails of slaughter across the Unadilla hills; and Joseph Brant defeated the Continentals at the Battle of Minisink. But the Iroquois were forced into defensive fighting in 1779 by the Sullivan-Clinton expedition, which devastated their homes and their cornfields and drove them north to seek British protection. From this blow the Iroquois never fully recovered.

When the Revolution ended the Indians were entirely destitute. Joseph Brant went to England in 1785 to plead for the welfare of his people. He was cordially received in London, hobnobbed with high society, paid a formal visit to George III, and returned with a grant for a reservation on the Grand River in Ontario.

Many Mohawks, Onondagas, and Cayugas accompanied Brant to Canada, but many more remained, and their plight was entirely tragic. The Continental Congress and the State legislature passed resolutions; treaties were signed; Indian commissioners were appointed; and after 1784 reservations were established in New York State for the Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga. The Seneca obtained 10 tracts of land by the Big Tree Treaty in 1797, and later deeded a small section to the Tuscarora.

In this time of need and distress appeared Ganeodaio ( Handsome Lake), who between 1799 and 1815 preached a doctrine of reform that became the most effective bar to the spreading of Christianity among the Indians.

He organized a characteristic messianic cult, like that of Tecumseh, the Shawnee prophet. Advocating strict adherence to Indian custom, he covered hundreds of miles on foot and preached a doctrine of chastity and temperance with an eloquence that gained many converts.

With the establishment of reservations, the Indian underwent a gradual metamorphosis. His warfare was obsolete. The small area of his habitations and the decimation of wild game made hunting unprofitable. Agriculture declined with the loss of land and the weakening of morale. Missionaries erected churches, Quakers established an Indian school, and the arrogant warrior became a disciple of the white man's progress. In the nineteenth century the Quakers achieved the only real success at making the Iroquois self-sufficient farmers.

Today practically the entire Indian population of the State, numbering approximately 5,000, is confined within the boundaries of reservations. Reservation Indians are a separate people, exempt from land and school taxes, and with power to regulate their internal and social relations. The only revenue the Indian receives from the Government is an annuity, under the early treaties, of from 68¢ to $1.35 and five yards of cloth, in addition to the rentals from his lands and their mineral resources. He ekes out a living by truck farming and by selling moccasins, splint baskets, and willowware. The State Department of Social Welfare provides the cost of home relief, medical care, and employment service, maintains an orphanage, and offers help in the improvement of agriculture; the Work Projects Administration has provided work relief and has sponsored a revival of the old handicrafts; and the State Education Department maintains Indian schools, though most pupils attend adjacent village schools.

The Indian's contributions to the civilization of the New World were of inestimable value. His cultivation of corn and tobacco, his vast knowledge of woodcraft and herbs, and his technique in trapping and hunting were all vital props in bolstering the self-reliance of the pioneering colonists. Even his methods of government were freely borrowed and used in the building of empire. Most definite, and lasting into our own day, has been the Indian contribution to place names, which has stamped upon the New York State map such names as Otego, Owasco, Canandaigua, Poughkeepsie, Schenectady, and Ticonderoga. Finally, the Indians left, hovering over brook and vale and mountain, legends of creation, of battles of gods and giants, of tragic elopements, of fools and wise men,—legends which, for the initiate, animate the landscape with a beauty and an interest beyond what the senses perceive.

|

|

This website is created and designed by Atlantis International, 2006

This is an unofficial website with educational purpose. All pictures, and trademarks are the property of their respective owners and may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever. If proper notation of owned material is not given please notify us so we can make adjustments. No copyright infringement is intended.