On the hottest day of the summer of 1935, thirteen-year-old Briony Tallis sees her older sister Cecilia strip off her clothes and plunge into the fountain in the garden of their country house. Watching Cecilia is their housekeeper’s son Robbie Turner, a childhood friend who, along with Briony’s sister, has recently graduated from Cambridge.

By the end of that day the lives of all three will have been changed forever. Robbie and Cecilia will have crossed a boundary they had never before dared to approach and will have become victims of the younger girl’s scheming imagination, and Briony will have committed a dreadful crime, the guilt for which will colour her entire life.

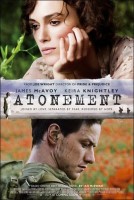

The filmmakers of “Pride & Prejudice” reunite for a new movie, based on the award-winning best-selling 2002 novel Atonement, which is a classic British romance that spans several decades. Fledgling writer Briony Tallis, as a 13-year-old, irrevocably changes the course of several lives when she accuses her older sister’s (Academy Award nominee Keira Knightley) lover (James McAvoy) of a crime he did not commit.

Adaptation

Even before Joe Wright had begun shooting his feature directorial debut, 2005’s Pride & Prejudice – which would ultimately earn him a BAFTA Award, among other honors – producer and Working Title Films co-chairman Tim Bevan realized, “We needed to plan on making this exceptional new director’s next movie. So we started to look for material that we might work on with Joe after Pride & Prejudice was finished.”

The new project would be another classic British romance from a great book; Ian McEwan’s award-winning best-selling novel Atonement was already in development at Working Title with producer Robert Fox and director Richard Eyre. But, as Bevan reports, “Richard took on another movie and had a stage commitment as well. Very honorably, because he absolutely loves Atonement, he said, that if we could find a director that we all agree we want to work with, then he would hand over the helm – and he did.”

The director was intent on bringing Atonement from page to screen. He knew that realizing the narrative would be an exciting filmmaking challenge. He comments, “In making a book into a movie, the story reveals itself to you as you make it. You are questioning the structure, you are questioning points of view – and, for Atonement, we were questioning one single truth as opposed to multiple truths.”

Academy Award-winning screenwriter Christopher Hampton had been adapting the novel. Wright explains, “When I was first sent the script, it had departed quite a lot from the novel. I thought the book was brilliant, and Christopher and I started again from scratch. The script was rewritten; we stuck to the book as faithfully as possible. “

“That was the approach that worked best,” confirms the screenwriter. “We returned to the structure of the book. The novel grows in power as the story progresses, and Joe and I wanted to stay true to that.”

“It was quite a fluid collaboration,” assesses Wright. “By the end, I felt I knew the book and knew the script totally, and understood every moment – or at least tried to. Then, I learned more and more about the material during shooting. A book is symbols and words on the pages; it happens in your head. As on Pride & Prejudice, I sought to make a film adaptation of the book that happened in my head as I read it. “

Paul Webster had already rejoined Working Title co-chairs Bevan and Eric Fellner as producer on Atonement, following their producing Pride & Prejudice together. Webster says, “I thought the book was Ian’s best, and most cinematic, work. Once our imaginative director started collaborating with Christopher, the script became richer and more complex. Joe brought a vast visual imagination to the film, and Christopher wrote a beautiful script – without what he calls the ‘convenient crutch’ of a voiceover.

“The themes Atonement addresses are so powerful and common to us all; emerging sexuality, intertwining fates, and that sense of ‘if only I’d have done this instead of that, my life would have been entirely different.’”

Bevan recalls discussing the difficulties of bringing Atonement to the screen. He notes, “The film was going to have to be all about the detail, about the times and about precision. It was going to need three different actresses to play the same role, and would use the device of multiple perspectives of the same event. It was going to be a very complicated piece.”

McEwan, who has witnessed his works being adapted for the screen on previous occasions, also knew the task would not be simple with Atonement. As he says, “It’s a kind of demolition job. You’ve got to boil down 130,000 words to a screenplay containing 20,000 words. In this particular case there are greater difficulties for the screenwriter because this is a very interior novel. It lives inside the consciousness of several characters. I think Christopher Hampton has steered a wise and clever course through the book.”

Hampton offers, “The best and most atmospheric of novelists are often the hardest to adapt. Yet, the adaptations that I’ve done that have given me the most satisfaction are from works – like Les Liaisons Dangereuses – that are masterpieces. I think Atonement is one of the best novels of the last 20 years, so to preserve its qualities was a great responsibility.”

Michiko Kakutani wrote in The New York Times [on June 1, 2007] that, in Atonement, the author “beautifully [explores] the precariousness of daily life and the difficulty of achieving – and holding onto – ordinary happiness.”

Wright muses, “Atonement, though set in the past, has contemporary relevance; it is about everyday experiences, relationships, emotions, choices, and decisions. As on Pride & Prejudice, I sought to interpret a period story in such a way that the modern-day audience is able to see beyond the time and setting of a story – and into the story itself.

“What I have learned from directing period pieces is that they free your imagination. If you utilize the specifics of a period very precisely in tandem with emotional truths, it all becomes relevant to a modern audience. In terms of the themes that Atonement deals with, it taught me a lot.”

Hampton adds, “The more accurate you are with presenting a period, the more striking the modern aspects of the story become. Audiences watching Atonement will see a completely different world than the one they know – and people in it relating to each other in wholly recognizable ways.”

Bevan concludes, “There is a fascinating emotional journey at the heart of Atonement. We all have to live through the circumstances of what we do at any point in our life, and this story is a very acute rendition of that.”

By the spring of 2006, the screenplay adaptation was at the 25,000 words it needed to be for a viable movie to be made.

Casting

As on Pride & Prejudice, Joe Wright made sure to cast actors who were of ages comparable to the characters they would be playing in Atonement. As before, he and the producers were set on Keira Knightley as their leading lady.

Wright clarifies, “I felt that Keira, who is such an intuitive actress, was ready to play Cecilia because the truth is that the part is a character role rather than that of the pretty leading lady. It’s a very complex role; Cecilia is not a particularly likable person to start with, but she is redeemed by her love of Robbie and by his of her.”

Knightley says, “I had a great experience on Pride & Prejudice; Joe is a sensational director. He makes sure that every actor sees the story from their character’s point of view. After reading Christopher Hampton’s beautiful script, I knew I wanted to play Cecilia.”

Paul Webster notes, “The strong working relationship that Joe and Keira developed over the course of filming Pride & Prejudice meant they had a mutual understanding and respect that would enable them to effectively approach Cecilia together.

Wright enthuses, “Keira was not afraid of playing Cecilia as cold and difficult, and awkward in her own skin. She was brave in taking this role, since many actors are terrified of being disliked as the characters they play on-screen. The resulting performance is, I believe, her boldest and strongest to date.”

For Knightley, there was considerable appeal in playing a character so different than any she has played in her career thus far. She explains, “The reason I liked this character is because she is a woman, of the kind Bette Davis might have played. She knows who she is, yet she doesn’t know which direction to go in, so she’s quite conflicted. She doesn’t realize that actually she fancies Robbie; she’s grown up with him, and at first won’t admit that there’s anything between them beyond a kind of brother-and-sister relationship. But, there is, and when we meet them they’re on the brink.”

The male lead role of Robbie Turner, the son of the Tallis family housekeeper with a Cambridge education courtesy of the Tallis family, called for an actor who, notes Wright, “had the acting ability to take the audience with him on his personal and physical journey.”

McAvoy saw the story as “epic, romantic, and really about what it is to be a human being. It affected – and still affects – me hugely, and I hope it will do the same to audiences. Atonement also explores the truth of how we are at our best when we are being attacked, and Robbie Turner is forced to fight on two fronts.”

Wright adds, “I’d first seen James in a play about seven years ago, and I could tell how good he was. I’d offered him parts twice before, and this third time was the charm. James has working-class roots, and that was very important; Robbie’s story is that of a working-class boy whose life is often at the mercy of the snobbery of an upper class family. James also has a deep soul, and isn’t afraid to show it. The character is described by Ian McEwan as having ‘eyes of optimism,’ and James has those. When he smiles, you smile; when he cries, you cry.”

McEwan adds, “Later in the story, it is written that ‘there is a stamp of experience in the corners of his eyes.’ Through James’ performance, you feel the pathos.” Even so, as McAvoy notes, “Joe would tell me, ‘Don’t beg them to cry,’ meaning, the audience. Robbie was one of the most difficult characters I’ve ever played, because he’s very straight-ahead. In the 1935 scenes, the family doesn’t see him as one of them, yet he doesn’t have a chip on his shoulder. Joe was very keen not to be manipulative with the audience, so he emphasized underplaying. So, later in the story, when Robbie explodes, you really feel it.

“As a director, Joe knows how to choreograph his scenes, understands the story he’s telling, respects his crew, and loves actors; he made me a better actor on Atonement.”

Knightley reveals, “Joe would direct us to deliver our lines swiftly; he wanted the dialogue scenes to play as they did in classic British movies. He likened it to rain pattering down, or bullets firing. Doing that informed our performances and showed us who our characters were; it was exciting to play, because that particular style of speaking is now lost. It’s like doing an accent, yet it made everything easier.”

Wright clarifies, “The actors in 1930s and 1940s movies had a naturalism to their performances. I wanted to recapture that with this cast; I showed them Rebecca, Brief Encounter – which James and Keira particularly adore – and In Which We Serve, to name a few.”

McAvoy laughs, “Keira just flew with that style of acting. For the rest of us, it took a little bit longer!

“Joe’s basic instructions to me were very simple; ‘Stop acting and stop trying. Less is more.’ He taught me to do away with acting that you think you need to do.”

McEwan says, “Keira and James are superb together. I particularly liked the scene in the library. This is a wonderful release of tension for Cecilia – a brittle upper-class young woman, divorced from her own feelings. In the library, she confronts them in a flood of strong emotion and erotic charge.”

Bevan adds, “James is poised to become a movie star; he gives a fantastic performance in Atonement.”

Casting not one but three Briony Tallises was a challenge the filmmakers happily met, albeit not in order of their on-screen appearances. While Academy Award winner Vanessa Redgrave was everyone’s ideal to play the older Briony, and committed to the role after one meeting with Wright, the younger incarnations proved tougher to cast.

After many auditions and much searching for an actress to play Briony at age 13, casting director Jina Jay (who also cast Pride & Prejudice) came across Saoirse (pronounced “sear-sha”) Ronan. The Irish actress, at the time 12 years old, has, according to Wright, “a keen sensibility which belies her years, making her perfect for the role of the young writer.”

The young actress saw her character as “a girl with a very creative imagination; she can go off by herself and write stories and plays. She makes herself believe things, and after a while, she decides to go with her imagination and to believe herself instead of anyone else.

“I felt so lucky to have gotten this fantastic part. Working with Joe – who explains everything so well and so clearly – and everyone was just really special. Hopefully I’ll be like Keira when I’m her age, making intelligent choices as an actress.”

On the set, Wright only grew more and more impressed with Ronan. He says, “So much rests on her shoulders in that first section. Without a brilliant Briony at age 13, we would have been in trouble…A lot of actors draw on their own emotional experience; in a way they substitute their characters’ emotion for their own emotion, and vice versa, and there’s no right or wrong way of doing that. “But Saoirse doesn’t. She purely imagined what it would be like to be Briony Tallis, who is nothing like her. Saoirse has such empathy that she can feel and express the emotions of another human being. That’s an incredible talent to have; every day she would surprise me, and fill all of us with awe.”

McEwan marvels, “What a remarkable young actress Saoirse is. She gives us thought processes right on-screen, even before she speaks, and conveys so much with her eyes.”

Speaking of which, adds Wright, “I consciously chose three actresses with strong eyes; Briony is the eyes of the film, which is conveyed when each of the three Brionys looks straight at the camera lens.”

Hampton remarks, “With these three actresses, there is no doubt that you are seeing Briony Tallis throughout the course of her life. The hospital sequences are particular favorites of mine; Romola Garai has a quality of gravity that enhances the second section of the film.”

Garai, who plays Briony at age 18, was the last of this trio to be cast. Accordingly, she was obliged to adapt her performance’s physicality to fit into the Briony appearance that had already been decided upon for Ronan and Redgrave. Garai rose to the challenge, spending time with Ronan and watching footage of her to approximate the way the younger actress moved. All three actresses worked with a voice coach to keep the character’s timbre in a similar range throughout the story.

Having read the book prior, Garai saw Briony as “an amazing character, and so precisely created. I usually play more outgoing characters, but after what happens in the first part of the story, Briony has become highly insular and not able to express herself.

“Joe does not have that problem; he’s so honest with actors in his directions. Since I have to follow Saoirse’s performance in the story, it was good to have someone who sees all for Briony and knows the character best; he was able to say, ‘This is what she’s thinking’ or ‘This is how she feels right now.’ With such a clear vision of what he wants the film to be, his was a working style that I really responded to.”

Tim Bevan observes, “Romola is one of a very exciting group of new-generation British actors right now. Joe has four of them in Atonement; James, Keira, Romola, and Benedict Cumberbatch.”

Cumberbatch is reunited with McAvoy after previously starring together in Starter for Ten; he was cast in Atonement as Paul Marshall, the chocolate company heir whose stay with the Tallises proves eventful in the first portion of the film.

In addition to Knightley, Wright was able to reconvene two more Pride & Prejudice actors; Brenda Blethyn and Peter Wight signed on for small but pivotal roles.

Preparation and Production

Even as Pride & Prejudice was still playing around the world, Joe Wright and the trio of producers were asking members of the team to ready for the new movie together. Executive producers Debra Hayward and Liza Chasin, and co-producer Jane Frazer, would again be on board.

More valued key collaborators encored; production designer Sarah Greenwood, costume designer Jacqueline Durran, composer Dario Marianelli – all of whom had earned Academy Award nominations for their work on Pride & Prejudice – and editor Paul Tothill. Cinematographer Seamus McGarvey and hair and makeup designer Ivana Primorac, who had themselves worked together on The Hours, newly rounded out Wright’s team.

Greenwood affirms, “Joe likes to run a film like a repertory company, using the same team. It’s a very creative way of working, and you can hit the ground running because there’s a shorthand.”

Paul Webster adds, “There’s also a trust and a strength that are gained from a director having a team back together. The ideas and information flow.” Wright meticulously prepared for production, actively engaging with every department early on to communicate his vision, in order that the “book that happened in his head” could be dramatized on-screen and that once filming began, everyone was on the same page of that book.

“He’s the most prepared director I’ve ever worked with,” states Webster. “Once he has the film in his head, he designs it shot by shot and scene by scene with the cinematographer. He plots out every location. Then, he shares all this information with everyone, which is – in my experience – unique for a director.

“Before shooting begins, we are given a plan of the film, with everything down on paper; shot diagrams, storyboards, pictures. On those occasions when it changes during production, everyone gets the updates. What’s especially exciting is that the camera becomes the writer.”

“Joe has a strong vision,” offers Durran. “He will be quite specific about the look he wants, but he will also be open to your suggestions.”

The director conducted a three-week rehearsal period with the cast, ensuring that by the time the cameras rolled all the actors were comfortable with their characters and the environment(s) they inhabited. This afforded several members of the cast the chance to confer with fellow actors who were in different periods of the story.

Vanessa Redgrave says, “Saoirse Ronan and Romola Garai and I did some improvisations on body language, among other things, for Briony. Joe – who is brilliant with actors – was able to pick and choose what he wanted focused on during the filming.”

Wright adds, “We had meals together and talked to each other so that everyone would be able to express their emotions, including when we began filming. This way, there was no tension blocking communication.”

James McAvoy reveals, “We also learned dances like the foxtrot. Now, there’s not much dancing in the film, but spending an hour every day for three weeks doing this made the cast bond.”

Research was actively encouraged; Keira Knightley’s extensive reading about WWII in the U.K. so fascinated her that she continued exploring those years even after production had wrapped. Actors met with real-life WWII nurses and war veterans, including soldiers who had been at the Battle of Dunkirk.

The three parts of the film were envisioned with very different identities and looks which Wright wanted to subtly convey to the audience through the camera work and different color palettes. This necessitated complete correlation between the director and his heads of departments – McGarvey, Greenwood, Durran, and Primorac in particular. Wright would communicate what he needed and wanted to the department heads, and the departments in turn would unify and enhance each other’s work with a shared sensibility.

The department heads worked with a historian and then went on to research and prepare for each part/period; they looked at paintings, photographs, and films, and searched archives for inspiration to fit the story. This was especially important with regard to the WWII era being re-created.

Given the director’s preference for location shooting, Greenwood joined location manager Adam Richards (also encoring from Pride & Prejudice) in spending months scouring the U.K. for locales that could stand in for the French countryside and the French port of Dunkirk.

Webster notes, “The luxury and beauty of 1935 is fully conveyed; so, too is war and loss during 1939 and 1940.”

Primorac crafted hair and make-up that would subtly convey each period as well as how the characters’ circumstances and experiences are affecting them through the years. She notes, “The 1935 segment at the Tallis house has a stylized 1930s look, one heightened to a level that the British aristocracy would not have practiced at that time; we have made their world more glamorous than it even was. There’s something of a dreamlike quality, as in Briony’s memories of happier times.

“In the second segment’s London scenes, the hair and make-up reflect the harsh realities of WWII.”

Marianelli was not on the set like the other department heads, yet in a way he was; Wright’s preparation had extended to having the composer prepare a score for the first day of shooting. The music, shared with the cast and crew, helped to set the tone for the shoot as a whole; other scenes were also shot to pieces of the score that the composer had readied.

Filming of the film’s three sections was done almost entirely in sequence. The first part of Atonement is set on the hottest day of 1935, at the Tallis family home in Surrey, where the heat seems to affect the behavior of the individuals staying at or visiting the house.

Keira Knightley says, “As the day progresses, you sense unease in the air. In the heat, everything is languid. The people at the house are speaking very fast, yet they can’t quite move the way they want to.”

Wright notes, “The story reveals itself in layers in this section, and it was a wonderful journey for all of us while we were shooting this portion.”

Set decorator Katie Spencer, who had been Academy Award-nominated in tandem with Greenwood for Pride & Prejudice, rejoined her in searching for the house that would best embody the one described in McEwan’s book. The duo visited the archives of the U.K. magazine Country Life in the hope that they would come across properties which could be used to film the interior and/or the exterior scenes at the Tallis home on the fateful day and night. Stokesay Court, in Shropshire, had been featured in the magazine and was deemed perfect for both interiors and exteriors.

The script was modified to take into account the realities of the location once it had been set – “a fantastic way of working,” enthuses Greenwood. Then, it took seven weeks of preparation to ready Stokesay for five weeks of filming. For the crucial sequence in which Cecilia and Robbie orbit each other as well as a fountain in the garden, Greenwood’s team built a fountain over and around the existing Stokesay pond. This afforded a protective measure for the intact original structure, as well as creating a setting that even more strongly complement the actors’ performances.

Knightley muses, “Stokesay was such a gift because it is a private home, so it was all ours; on Pride & Prejudice, we had beautiful locations where we would be doing intimate scenes –while tour groups were there taking pictures…

“Joe brought us in a day ahead of the shoot, so we could spend time in our bedrooms and walk around the grounds. To be able to do all the interiors there as well was extraordinary.”

McAvoy concurs, noting, “We stayed there for the whole shoot. There wasn’t a couple of minutes’ drive to the set each morning; it was a couple of minutes’ walk. Joe knew we would get a sense of ownership, in addition to a sense of space and place. I think that familiarity comes across on-screen.”

Greenwood adds, “We shot at Stokesay during the summer. It was very lush there, and luckily they’d had a lot of rain so there was a very verdant quality to the grounds. Even luckier, it really was very hot during shooting!”

Webster notes, “Sarah and Katie really got into the detail of the story, and paid special attention to what was going on in design in the 1930s. In the first part, everything is ripe to the point of corruption, and they have used the patterns of chintz – which are quite popular today as well. The wallpapers and fabrics and Jacqueline’s costumes were all crucial to getting across this very dense and rich pattern-upon-pattern ideal.”

Greenwood reveals, “The main difference between Jacqueline’s costumes and the patterns that my department was using is that her colors are more vibrant than ours; ours were held back, so you have a separation that gives that much greater a contrast between what you see in Surrey and what you see subsequently in London and Dunkirk. The environments are at opposite extremes, so there has to be a juxtaposition of imagery.”

Mc Garvey worked closely with Wright on how the different parts of the film would look. The director says, “Seamus and I used the camera not only to capture the story visually but also as a storytelling device in itself, through the movement and techniques applied.”

“At the start of the film, there is dynamism with the camera,” notes McGarvey. “There’s a rhythm; Briony is restless and full of creative energy, so it’s as if she is pulling the camera all over the house and the grounds. Joe didn’t want to luxuriate in the period too much; certainly, everything is beautiful, but all the departments also concentrated on making everything look and feel vital to the story.

“The lustrous quality of the 1935 scenes was achieved by using particular filters – and, older Christian Dior stockings! – over the lens, which created a beautiful glow. There’s a lot of blue in the first part. When things take a darker turn in the first portion, we continue to use the filters, but that sweetness becomes more saccharine. There is a darkness that keeps surfacing, and which is progressed and built upon in the other parts of Atonement.”

Durran adds, “Joe and I talked about how that summer day is the last perfect moment, before the fall – in both senses of that word.

“With Cecilia in the first part, the idea was that everything she wear be light and transparent, almost like a butterfly. For the backless evening dress, Joe wanted something that would flow because Keira would have to run in it. So we created a fuller skirt and narrower hips, and we picked this specific shade of green. Keira was involved in the process, so it really was a collaboration.”

Knightley enthuses, “Jacqueline and her team made such beautiful clothes for me to wear as Cecilia in the 1935 scenes. They did an absolutely incredible job!”

Primorac says, “Keira has less vanity than anyone I’ve ever met. When we were working guidelines out for Cecilia in 1935 – how stiff the waves in her hair would be, for example – Keira was ready for whatever was right for our story.

“When the war starts, we had to convey how Cecilia doesn’t have as many resources; she still does her hair, though not as often. The temptation was to go outright from glamorous in the first section to dowdy in the second section. But that’s not Cecilia; she would still put on lipstick if she could get one, or had one left over.”

In the three parts, three different actresses progressively incarnate Briony Tallis. But a distinct look for the character, and the actresses, had to be maintained through hair and make-up as well as costuming.

Durran elaborates, “This meant keeping the color palate similar; so, because we start off in the first part with Saoirse in blue and off-white, we carry that on to the pale blue-and-white of Romola’s nurse’s uniform. These colors remain consistent for when you see Vanessa in the third part, wearing a dress that has elements of the dress that Saoirse wears in the first part.

“What I aim for, most of all, is that the costumes contribute to the actors’ performances and adds something for them and Joe to work with.”

Primorac and her department paid special attention to everything to the three Brionys. She notes, “We tried to make the lips into similar shapes, and matched their eyelashes and cheekbones. Giving them the same texture of hair tells you, ‘This is Briony.’ I think we succeeded because of the skill of these actresses, with Saoirse setting the tone.

“The London section was quite complicated because of Briony’s working in the hospital, and the wounds that she tends to. But Joe’s process is so detailed, and he has researched everything himself, so we knew what was called for.”

Also for the second part, McGarvey and Wright adapted the camera technique to convey the change from the rich hues of the Tallis house to grittier wartime London and France. The cinematographer says, “The Dunkirk sequences are more symmetrical; with the homefront in London – and the war hitting home – we adopt a more handheld and jagged approach to the cinematography. That applied to the light as well, which becomes harder and more brittle and abrupt; there’s more contrast in the visuals.”

Only eight U.K. military ambulances from WWII remain, and Atonement made use of them all. Uniforms from WWII were also used, but Durran had to have the majority made, given how many extras would be in the scenes. She notes, “We sourced original webbing, original helmets, and original hobnail boots, among other elements.”

All of the nurses’ uniforms had to be created, again with originals as reference points. Durran clarifies, “With the blue-and-white stripes, we did effect a change from the original lilac-and-white; we also modified what is worn in once scene, for dramatic purposes. All else, we got as right as we could, down to the Nightingale badges being reproduced for those qualifying nurses; you see Cecilia still wearing one, but by that point in the story she has moved on to another hospital.”

When WWII sends Robbie and his British Expeditionary Force (BEF) unit through France, the full scale – human and spatial – of the army’s retreat from and at Dunkirk is captured in a single shot worked out by Wright and McGarvey with steadicam operator Peter Robertson.

Wright says, “The sequence was originally scripted as a montage. But that would have required 30-40 set-ups in a single day, with consistent light. So we went a different route.”

McGarvey adds, “We wanted something that would evolve within the scene itself, and was appropriate for the context. The conventional way to shoot what Robbie is seeing would be to go for a wide shot with a longer lens. With this shot, you are with Robbie, so you share his point of view and also see his face, his reaction to it all.”

The sequence was filmed on location at the seaside town of Redcar, with its existing beach and Corus Steelworks industrial landscape; 1,000 locals were employed to portray wounded or dying U.K. soldiers stranded on the beach at Dunkirk while awaiting safe passage home in 1940.

Greenwood notes, “Joe wanted the scale to be fully conveyed. To me, this shot says everything about Dunkirk – and about Robbie’s journey.”

Ian McEwan reveals, “My father was in or attached to the British army for 50 years. He was on the beach at Dunkirk, severely wounded and then evacuated. When he talked about it, you could see the darkness of the memory, yet also the sense that it was when he felt most fully alive.”

McAvoy reflects, “We talked to one veteran who couldn’t tell us a lot. He said, ‘When you’re doing it, boys, just think about how bad it really was.’ It was hard for him to even say that to us.”

All departments worked together to marshal for the sequence – among many other elements – a bandstand, French and British army weapons both vintage and re-created, a working ferris wheel, bombed-out buildings, a huge beached Thames barge, a choir in performance, and show horses.

In the five-and-one-half minute uninterrupted shot, the camera follows James McAvoy, Daniel Mays, and Nonso Anozie – as Robbie and the two other surviving British soldiers from his decimated unit – as they tenaciously search for any quieter space to try to decompress in.

Webster says, “James’ powers of concentration and transformation impressed me all through the shoot. When it came time to shoot this sequence, he was moving through it all and reacting – which, in a way, is the hardest kind of acting. Robbie witnesses a lot, and James conveys his inner state brilliantly.”

Tim Bevan comments, “In all of our movies, we’ve only ever done one sequence even close to this; this is epic, and spectacular – but the spectacle is there to emphasize the very emotional feeling of the sequence, of how it was for these young men nearly 70 years ago.

“The shot is also an example of the magic of cinema when you have something epic like this, you catch it on film, and then it’s gone – in terms of the set and the moment. Then it lives forever in the movie.”

McGarvey elaborates, “It was what filmmaking is all about – collaboration. Bear in mind that in addition to the 1,000 extras, there were 300 crew members at work – all without a weak link in the people chain.”

Wright remembers, “It was very, very exciting and I loved doing it. We spent all day rehearsing it, from 6 AM to 6: 30 PM. The next day, we did one more rehearsal and then shot three takes. It became like a piece of theatre. The light was amazing; I had faith that it would be. We were all was so engaged and involved; everybody realized what we were trying to achieve.”

Throughout post-production as well, departments worked in harmony, with special regard to the sound and editing processes. From the enhanced sound effect of rushing water when Cecilia emerges from the Tallis estate’s fountain to the clipped upper-class accents of the Tallis family to the interweaving of the sound of typewriter keys into Dario Marianelli’s score, every detail was worked out and unified.

Wright notes, “Our editor Paul Tothill is a master of sound, and we built up the sound as we edited. We wanted to make the picture and the soundtrack into an integrated, cohesive whole. Dario would give us so much to work with.”

For scoring, Marianelli reconvened key Pride & Prejudice collaborators, including – to perform the score he composed – the English Chamber Orchestra.

“Atonement is a cinematic symphony,” assesses Redgrave. “In cinema terms, it’s a real film – and a heartrending one.”

Christopher Hampton says, “Joe has a strong grasp of what’s doable in the editing room with Paul. The finished film moves like an express train.”

Wright says, “The nine-month post-production process was delicate; we had to be sensitive to what the material was telling us. All the way through, our producers made me more confident on Atonement than even on Pride & Prejudice.”

Bevan comments, “Joe is still hungry; he’s always the one to leap from the front, be up earlier and work later, and always striving for a greater quality.”

Paul Webster adds, “He’s a great romantic who communicates philosophical themes and ideas in cinematic form so that they are comprehensible to the filmgoer. Like all good artists, he explores stories that reflects himself and his view of the world.”

Wright concludes, “I’m honored to have had the chance to make this film, and to have worked with the people I did on it.

“Atonement is so close to me that I cannot look at it objectively; but, other people’s work, I can look at objectively – and I am incredibly proud of what our cast and crew achieved.”

The Locations

As with Pride & Prejudice, Atonement was made by the filmmaking team on locations all over Britain. Some of the specific shooting sites were; Stokesay Court, Shropshire Stokesay Court is a Victorian house (built in 1889) which forms part of the privately owned Stokesay estate in the county of Shropshire. All the exteriors and interiors of the Tallis home and the Turner cottage were filmed at Stokesay.

London

London locations included Whitehall and Bethnal Green Town Hall. The latter was used for the scene where Cecilia and Robbie are reunited in 1939 at a tea house.

The underground Balham station scene set in 1940 was filmed at the closed tube (a.k.a. subway) station Aldwych.

A street in the Streatham neighborhood was dressed for the scene set in Balham when Briony, at age 18, is looking for where Cecilia is living.

The St. Thomas’s hospital ward interior and corridors were built as a studio set at Shepperton Studios. However, the hospital’s storeroom, day room, and nurses’ dormitory scenes were filmed at Park Place, Henley Upon Thames; the exterior of the hospital was actually University College.

The wedding scene was filmed at St. John’s Church, Smith Square.

The third portion of Atonement was filmed at the BBC Studios in Wood Lane.

Dunkirk and the French countryside

The scenes with Robbie and his fellow soldiers making their way through the French countryside en route to Dunkirk were filmed in Coates and Gedney Drove End, in Lincolnshire; in Walpole St. Andrew and Denver, in Norfolk; and in March and Pymore, in Cambridgeshire.

The poppy field scene was shot in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire.

The light industrial quarter scenes were filmed at the Grimsby fish docks; the heavy industrial quarter, as well as the marshland, scenes were filmed at Corus Steelworks, in Redcar. The latter’s beach was the site of the Dunkirk beach sequence, and also stood in for the Bray dunes.

The French cinema at Dunkirk that Robbie drifts through was in fact Redcar’s venerable Regent Cinema, which is located on the pier at the beach.

Production notes provided by Working Title Films, Focus Features.

Atonement

Starring: Keira Knightley, James McAvoy, Romola Garai, Brenda Blethyn, Vanessa Redgrave, Anthony Minghella

Directed by: Joe Wright

Screenplay by: Christopher Hampton

Release Date: December 7, 2007

MPAA Rating: R for disturbing war images, language and some sexuality.

Studio: Working Title Films, Focus Features

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $50,927,067 (39.7%)

Foreign: $77,468,517 (60.3%)

Total: $128,104,912 (Worldwide)