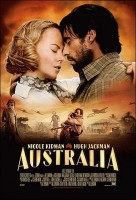

“Australia” is an epic and romantic action adventure, set in that country on the explosive brink of World War II.

An English aristocrat inherits a ranch the size of Maryland. When English cattle barons plot to take her land, she reluctantly joins forces with a rough-hewn cattle driver to drive 2000 head of cattle across hundreds of miles of the country’s most unforgiving land, only to still face the bombing of Darwin, Australia by the Japanese forces that had attacked Pearl Harbor only months earlier.

Set in Australia on the explosive brink of World War II. In it, an English aristocrat (Nicole Kidman) travels to the faraway continent, where she meets a rough-hewn local (Hugh Jackman) and reluctantly agrees to join forces with him to save the land she inherited. Together, they embark upon a transforming journey across hundreds of miles of the world’s most beautiful yet unforgiving terrain, only to still face the bombing of the city of Darwin by the Japanese forces that attacked Pearl Harbor.

The Faraway Of The Faraway

An epic tale of transformation, love and adventure, AUSTRALIA unfolds on the continent that director Baz Luhrmann sees as the world’s last great frontier. “To the rest of the world, Australia is the faraway of the faraway,” he says. “There’s a great line in the beginning of `Out of Africa,’ when Karen Blixen finds out that her husband is having an affair and she says, `I’ve got to get away, I’ll go anywhere. Africa, Australia…well, maybe not Australia.’”

Luhrmann grew up in a small lumber town in northern New South Wales, where his family ran a farm, the local gas station and, for a short time, the movie theater. “The movie musical was a great childhood love of mine, but I was also a big fan of the historical epic,” he says. “Epics were the kind of movies that you would hear about for weeks before the films actually arrived, and every single person in town would go to see them. You can imagine the impression made on a small boy in rural Australia by films like `Lawrence of Arabia’ and `Ben Hur’ – big, romantic adventures set in distant, exotic locales where the landscape amplified the inner emotional journeys of the characters.”

Particularly appealing to Luhrmann was the idea of creating an epic film set in his homeland that, like the classics that so influenced him in childhood, would have broad appeal across all generations of people around the world. “When watching these kinds of films, from `Gone with the Wind’ and `Ben-Hur’ to `Lawrence of Arabia’ and `Titanic,’ the audience was communing in one big motion picture experience,” he observes. “I wanted to create a cinematic work that would be similarly inclusive because I feel passionately about having more inclusiveness in our lives. Bringing people together brings comfort to the heart and soul in this unpredictable world.”

In the tradition of films like “Casablanca,” “Titanic” and “Oklahoma,” Luhrmann’s AUSTRALIA is a metaphor for the feelings of mystery, romance and excitement conjured by a distant, exotic place where people can transform their lives, spirits can be reborn, and love conquers all.

“This is the film I’ve wanted to make since I was a little girl,” says Nicole Kidman. “I grew up watching Australian actresses like Judy Davis in `My Brilliant Career’ and Angela Punch McGregor in `We of the Never Never’ playing wonderful characters in stories set in our country, and I dreamed of making a film here that had the passion and weight of those movies.”

“It’s the opportunity of a lifetime,” Hugh Jackman says. “I hadn’t done an Australian movie in eight years, so to come back and make a film of this magnitude, scale and ambition – using my own accent! – was a dream come true. Dream role, dream movie, dream cast, dream director.”

Jackman, who has known Kidman for many years (he is married to a good friend of hers), was impressed from the outset by the actress’ passion for the project and her trust in Luhrmann. “Nicole was at my house for a Super Bowl party,” he remembers. “Baz had just called me about the project, and I asked Nicole if she had read this script. She said no. I said, `Oh, Baz said you were doing it.’ She said, `I am.’ I said, `But you haven’t even read the script!’ She said `You don’t need to read the script, just do it. It’s going to be amazing. You’ll never have a better job in your life.’”

“If Baz asked me to say one line in something, I would say yes,” Kidman attests. “I believe in him. I believe in his talent. I believe in his commitment to putting beauty in the world and to his pursuit of excellence. It’s a privilege to work with someone you feel completely safe with, someone who is bold and innovative and uncompromising. I won’t lie and say it’s easy, because it’s not. It’s really hard. But when you make a big story there’s going to be hardship attached to it. We understood that from beginning, and I’m glad to be along for the ride.”

The story of AUSTRALIA is set in motion by Kidman’s Lady Sarah Ashley, a headstrong British socialite lost in a loveless marriage and a staid, superficial life. “At the age of 40, Sarah has poured herself into objects of perfection and control,” Luhrmann says. “The only thing that she truly loves are her horses.”

Convinced that her husband is cheating on her during his trip to Australia to sell Faraway Downs, their struggling cattle ranch, Sarah travels from London to the rugged wilderness of the Northern Territory to confront him. The truth proves to be as harsh as her new environs, and it propels Sarah on a journey of profound self-discovery.

“When she first arrives in Australia, Sarah is as uptight as Katherine Hepburn’s character in `The African Queen,’” says Luhrmann. “She is closed off to life and to love. But at Faraway Downs and beyond, she is forced to engage with the landscape and with the people, and she experiences a rebirth of spirit. She is completely transformed by the journey.”

Faraway Downs is an immense property the size of Maryland, situated in the unforgiving Outback and populated by an eclectic mix of cattlemen, servants and indigenous tribesmen. “It’s the antithesis to anything Sarah has ever experienced,” Kidman says. “But during the course of the story, she sheds a lot of the barriers that she’s built up to protect herself. She becomes the woman she truly wants to be, and she finds love – for a child, for a man and for the land.”

Sarah surprises herself and others around her when as she rises to the challenges of her new life and responsibilities, but nothing and no one challenges her more than the Drover. As rugged as Sarah is refined, the Drover is the best of a breed of man who drive herds of cattle across hundreds of miles of brutal, unforgiving terrain. As Jackman explains, “A good drover will get your cattle to market in better condition than when they left. When you consider the size of the herds and the vast landscape they travel through, that is no small feat.”

The Drover is a superb horseman who prefers to live under the sun and stars, a nomad and a solitary man. “He’s more comfortable out there with his horse and the cattle than he is with people,” says Jackman. “He’s his own man. He doesn’t want to be beholden to anybody, which is why someone like Lady Ashley presents quite a few problems for him.”

Sparks fly – in all the wrong directions – from the moment these two extremely contrary characters cross paths. Sarah is haughty and dismissive of the Drover, and he is equally irritated by Sarah and all that she represents. “The Drover hates the wealthy, land-owning Establishment, and Sarah is the poster girl for the aristocracy,” Jackman says. “He takes delight in shocking and teasing her, because everything about her annoys him. She’s arrogant, pretentious, frustrating and impossible.”

Despite their differences, Sarah and the Drover need each other – and the money they’ll earn if they can pull off a near-impossible drove of 1,500 cattle across the Kuraman Desert to market in Darwin. As the combative pair ready their misfit team of ranch hands and homesteaders to embark on the daunting expedition, tragedy strikes. A young Aboriginal boy called Nullah is left orphaned, and Sarah is thrust into a role that she had long ago given up hope of ever experiencing. “Caring for the boy awakens something in Sarah, and she finds unexpected strength and confidence as a mother,” Kidman says.

The situation is complicated by the fact that Nullah is a “half-caste,” or a half- Aboriginal, half-Caucasian child. In the segregated society of Australia in the 1930s and 40s, interracial marriage was illegal, and the children of illicit bi-racial relationships were forbidden from living among whites or with their Indigenous families. In a misguided attempt to lift these children out of poverty and offer them the possibility of a more rewarding future by distancing them from their Indigenous communities, the Australian government launched a nationwide program in which the children were taken from their families and placed in church missions or state institutions.

Part-Aboriginal children in particular were deemed as “salvageable” and removed from their traditional culture in an attempt to re-educate them. These children have come to be known as the “Stolen Generations” and, while statistics are murky, it is believed that between one-tenth and one-third of all Indigenous boys and girls were taken from their parents and relocated. “This is the world into which Nullah is born,” Luhrmann notes. “He is both black and white in a world that cannot tolerate having such individuals integrated into their society. Ultimately, Sarah defies the social order and gives him a home. In turn, Nullah is the catalyst that opens Sarah’s heart and brings her and the Drover together.”

Sarah’s newfound warmth and openness transcend the barriers she has put up between herself and the world around her, allowing the Drover to see another side of this complex woman. “In crisis, she’s truly amazing,” Jackman says. “The Drover comes to really respect and admire her.”

among Indigenous people and marrying an Aboriginal woman. According to Jackman, “He lives somewhere between the two cultures, but he is not really a part of either.” The Drover has spent years trying to bury his anger over the loss of his wife, who died from tuberculosis because Aboriginal people were not allowed in hospitals. “He’s built a wall around his heart with his anger,” says Jackman, “but those walls start to break apart as he comes to know Sarah better and becomes a kind of father figure to Nullah.” Under the awesome power of the landscape, transformed by the love of a child, Sarah and the Drover fall in love. “When everything else falls away, they find each other,” as Jackman puts it.

“There is something really beautiful about how Sarah and the Drover change together,” Kidman says. “This amazing boy brings them together and causes them to really look at why they are here in the world. I think that’s the magic of children. They look right into your soul and teach you about yourself. That’s what Nullah does for Sarah and the Drover on a deeply emotional and spiritual level.”

Nullah is portrayed by 13 year-old newcomer Brandon Walters, who was discovered at a public pool in his hometown of Broome during an intensive nationwide casting search for an Indigenous boy to play the pivotal role. Casting director Nikki Barrett spent months traveling to remote parts of the continent and auditioning nearly 1,000 young Aboriginal boys, most of whom, like Walters, had no acting experience or training.

Luhrmann narrowed the field of potential Nullahs from hundreds to ten finalists, prompting Walters to leave Western Australia for the first time in his life and travel to Sydney, where the director conducted workshop sessions with the prospective young actors. “I was immediately struck by Brandon’s natural talent and charisma,” Luhrmann recalls. “He and Nullah share a similar spirit.”

“Everyone in my family was so happy when I got the part,” says Walters, a cancer survivor who battled leukemia when he was just six years old. “I told my Mum when I grow up, I want to be an actor. Then I got this role, and I hope to act in more movies.”

Walters’ preparation for the film included training in horseback riding and cattle driving techniques (he especially enjoyed learning to crack a whip), singing lessons and dialect coaching. “The demands of filming over six months are incredibly challenging, especially for a young boy with no acting experience,” says Luhrmann of Walters, who was only eleven during production. “Brandon impressed everyone on the cast and crew with his stamina and enthusiasm.”

“I fell head over heels in love with Brandon,” Kidman says. “He’s very special. He taught me a lot about his culture, and it was magical to see the world through his eyes. He still has so much wonderment.”

Sarah’s new family is torn apart when government authorities capture Nullah and spirit him away to Mission Island to live with other banished half-caste children. Her decision to wage a one-woman culture war to bring Nullah home – as an even greater threat from Japan looms on the horizon – is the culmination of Sarah’s transformation. “In this world, it’s the people you’re connected to, the people you love and are loved by, who help determine who you are and what you become,” Kidman muses. “When you realize that, I think you find peace, and that’s what happens with Sarah. Even though she’s feels like she’s fighting against the world, she is at her most authentic and true because she realizes that she has something to fight for.”

Kidman kept a diary during filming, infusing her performance with her own personal experience of getting to know Australia on a deeper level. “I now have really seen the magic of what we have here,” she says. “And I do mean magic. The intoxication of it is powerful. There’s something in the air, the earth and the nature of the people that just captures you, and before you know it you’re a part of the land.”

Kidman and her costars also relished the opportunity to work with an ensemble cast comprised of many of the country’s great acting legends, including Australian film icons Bryan Brown and Jack Thompson; David Gulpilil, the country’s most renowned Aboriginal dancer and musician; and veteran film and television stars David Wenham and Ben Mendelsohn. “It was a great honor to turn up on set every day of a film called `Australia’ and work with some of the greatest actors that this country has ever produced,” Jackman says. “It’s a real testament, not only to what this film means to our country, but also to what Baz means to all these actors. People jumped at the chance to be a part of it.”

David Wenham, known internationally for his roles in “300” and “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy, plays Faraway Downs’ scheming station manager Neil Fletcher. A ruthless saboteur, Fletcher is secretly plotting with cattle baron King Carney to take over Sarah’s property.

Faraway Downs is the only major cattle farm in the country that King Carney doesn’t own, and he’s determined to ruin Sarah, if that’s what it takes to expand his empire. “King Carney is a businessman driven by huge ambition,” says Bryan Brown, star of such hit films as “Breaker Morant,” “Gorillas in the Mist” and “FX,” as well as the seminal 1980s miniseries “The Thorn Birds.” “He can be very generous and benevolent when he’s winning, but when he’s losing, don’t get in his way because he will walk all over you. It was good fun to play a character as colorful as Carney. He’s part bully, part charmer. He chops and changes as the mood befits him.”

A testament to Brown’s renown is Luhrmann’s enthusiasm over his participation in the project. “I was in a movie with Bryan Brown when I was a young boy. Bryan Brown! And now he’s in a movie I’m making,” the filmmaker marvels.

He was equally thrilled to cast Jack Thompson as Kipling Flynn, Faraway Downs’ alcoholic but benevolent accountant. “Jack Thompson is the Orson Welles of Australia,” Luhrmann believes. “He is the grand statesman of Australian actors.”

Thompson actually worked on a cattle station when he was fourteen. “In those days in the bush, nobody knew you, your name or what your real story was. It was considered rude to ask,” he recalls. “Kipling Flynn is representative of the kind of characters you would find in the Outback at that time, people who were unable to function in normal society. Flynn is running from the shame that he has brought on his family, and Faraway Downs is about as far away as you can get. He’s made his little office under Sarah’s house into his hideaway.”

The stellar ensemble also features David Gulpilil as King George, a mysterious Aboriginal shaman who teaches Nullah the ways of Indigenous magic; David Ngoombujarra as Magarri and Angus Pilakui as Goolaj, the Drover’s trusted stockmen; Lillian Crombie as Faraway Downs’ spirited housemaid Bandy Legs; Yuen Wah as the laconic cook Sing Song; and Ben Mendelsohn as Army Captain Emmett Dutton.

“These are all people that I’m really glad to be able to say that we’ve made a film together, to have shared this gorgeous experience,” Kidman says. “I’m very grateful for the opportunity to be a part of this project, especially at this stage of my life, when I’m now married to an Australian-New Zealander. It’s a wonderful way to give back to my country, which has given me so much in support of a career that has me working internationally.”

For Luhrmann, Lady Sarah Ashley and the characters that populate AUSTRALIA exemplify his personal and professional motto: “A life lived in fear is a life half lived.” “The job I do is about getting up every day and facing fear,” he says. “Every day on set I would look at the monitor and see Nicole Kidman in clothes that should never be worn in a desert, clumping through 100 degree heat being glamorous and funny. Or Hugh Jackman galloping into frame on a horse, nearly keeling over from dehydration. Sometimes I asked myself if we set the bar too high.

“But I am addicted to the pursuit of extraordinary living, and that means you have to set the bar high, and setting the bar high means you’re going to be confronting fear all the time. In the end, all you own is your story. So making it a good story, wanting to live a full life, a full adventure, to not live in fear and turn away from the possibilities that life presents, that is something I genuinely believe in and tried to bring to this film.”

The Road To Oz

Never before has an Australian filmmaker attempted a project of such epic scope and ambition set in country. AUSTRALIA marks the culmination of a deeply personal journey for director Baz Luhrmann, and is a testament to the power and influence of Australian cinema.

The country began making an impression on international movie audiences in the 1970s, when government funding for Australia’s burgeoning film industry launched a wave of breakout hits such as “Picnic at Hanging Rock,” “My Brilliant Career,” “Breaker Morant” and “Gallipoli.” The blockbuster “Mad Max” and “Crocodile Dundee” phenomenons of the 1980s piqued worldwide interest in the alluring land Down Under and popularized stereotypes of the larger-than-life characters that spring from its vast, untamed landscape.

With the release of the thriller “Dead Calm” in 1989 (starring a then-unknown Nicole Kidman), the 1990s ushered in a prolific era of smaller scale, highly acclaimed Australian films, including “The Piano,” “Flirting” (also starring Kidman), “Proof,” “Romper Stomper,” “Sirens,” “The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert,” “Muriel’s Wedding,” “The Sum of Us” and “Shine.”

Luhrmann burst onto the scene in 1992 with the release of “Strictly Ballroom,” an audacious comedy of dance manners crackling with energy, style and romance. “William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet,” his searing, modernized adaptation of the Bard’s classic, and the dazzling Academy Award-winning musical “Moulin Rouge!” firmly established Luhrmann as an innovative filmmaker with unique vision and a highly stylized, music driven cinematic language all his own. (Credited with reviving the long-dormant musical film genre, “Moulin Rouge!” was recently named by Entertainment Weekly magazine as number 10 on its list of 100 New Classics of the last 25 years.) It was with the completion of this “Red Curtain Trilogy” – and after directing a Tony-winning version of Puccini’s La Boheme on Broadway – that Luhrmann began developing a series of epic films, including a project with Leonardo DiCaprio about Alexander the Great. But after two years of intensive research across Jordan, the deserts of Morocco and the jungles of Thailand with his wife and creative partner, Catherine Martin, the project was shelved when Oliver Stone’s Alexander film went into production.

“I was tremendously disappointed when our Alexander project fell apart, so I went on a journey on the Trans Siberian Railway to clear my head after focusing on it for such a long period of time,” says Luhrmann, who later joined his wife and young daughter in Paris. “We decided to spend time in Paris to regroup, recharge our spirits and assess what our next creative step would be. We began to discuss our little girl’s life. There is no border between our life and work, and due to the nature of what we do, our children will always be part of a traveling circus. But, we asked ourselves, Where is the place they’ll call home? Where will their roots lie? This, more than anything, prompted our desire to reconnect with Australia.”

While traveling back to Sydney from Paris, Luhrmann began to imagine a story about a main character who embarks on a great journey that transforms her in a profound way. “It is the issue of transformation that I am most interested in exploring at this time,” the director explains. “I recognize a feeling that exists in me and my generation that at a certain age, you get locked into a pattern of life that will remain constant for the rest of your days – growth simply stops. So I was very interested in the idea of growth and rebirth. Secondly, life in the post-9/11 world has created an unnerving environment in which the future seems unpredictable and precarious. So I was also interested writing a story about characters who live in uncertain and tumultuous times.”

Another important theme emerged for Luhrmann as he developed the character of Lady Sarah Ashley, a woman whose static life is transformed when she is plunged into upheaval during her journey to the farthest reaches of Australia’s Outback. “We are living in a moment in time in which the forces of change are so great that the only act that truly empowers us is to defend the love that we believe in,” he says. “On a personal level, I came to realize that if I am surrounded by the people I love, and especially by my family, then even during these volatile times I have everything. I have a truly vital and meaningful existence. This is the realization that Sarah comes to as a result of her transformation. Even if honoring your relationships means defying everything and everyone to be together, you do what you must do to be with the people you love.”

The wild, untamed world of Northern Australia in the late 1930s and 1940s, with the looming shadow of World War II darkening its shores and divisive governmental policies tearing families apart, provided a rich canvas on which to bring these themes and issues into relief. Luhrmann and his wife, production and costume designer Catherine Martin, conducted an intense period of meticulous research into the era.

“We always start our process in reality,” says Martin, winner of two Academy Awards for production and costume design on “Moulin Rouge!” “Baz is exigent in insisting on accurate historical investigation so that any divergence from the facts is made consciously.”

“The DNA of this film comes from classic epic romances, but we had to find our own particular cinematic language to tell this story,” Luhrmann elaborates. “While we compress geography, time and some facts to amplify the drama and romance, we never change the fundamental truth in which the world of the film is set.”

During his research, Luhrmann became fascinated by the collisions of cultures and ethnicities living in Darwin, a thriving waterfront outpost in Australia’s “Top End,” the northernmost part of the sparsely populated Northern Territory. “Darwin at that time was a bit like the Wild West or Africa, because it was a vast, inhospitable place that could swallow you up. It was the end of the world, and at the end of the world you find extreme characters. There was an extraordinary clash of peoples. There was the Anglo administration under English control, cowboys and gold-rushers, a huge Asian influx, Greek pearl divers and a significant Indigenous population.”

This melting pot at the end of the world was rocked by war in February 1942, when Japanese warplanes – the same fleet that had bombed Pearl Harbor – attacked Darwin, killing 243 people and all but destroying the town. The tragic event is not well known outside of Australia. “I’m a history buff, so I knew a lot about it,” says Hugh Jackman, “but what I didn’t know – and what will come as a shock to many people – is that the Japanese bombed Darwin with twice the airfreight they used to attack Pearl Harbor.”

Luhrmann incorporated the bombing of Darwin into his narrative as a fulcrum for Sarah’s journey of self-discovery. He also drew from history in depicting the Japanese forces’ invasion of “Mission Island,” a fictitious settlement of bi-racial children who were, at the behest of the government, separated from White society and their Indigenous communities and placed in the care of missionaries. “While the attack on `Mission Island’ is a mythical telling, there are documented cases in which Japanese troops landed on Australian islands and attacked, captured and killed priests and mission staff,” Luhrmann says. “We took these real-life accounts and rewove them into our story.”

To further his understanding of Australia’s relationship to its Indigenous people and the controversial issue of the Stolen Generations, as these half-Aboriginal, half- Caucasian children who were excised from society have come to be known, Luhrmann traveled to Bathurst and Melville Islands to speak to men and women who had been mission children. “Working with our Indigenous partners in the telling of the Stolen Generations led to a theme that we have tried to touch on in the film,” the director relates. “It is the idea that you cannot really possess anything; not land, not a person, not a child. Real love makes you realize that you are only a caretaker for these things. All that you do possess at the end of a life is your story, and stories live on in the physical landscape.”

Setting AUSTRALIA in this particular period of the country’s history allowed Luhrmann to explore another crucial aspect of its culture and economy. “One of the underlying pleasures of this film is that we’re able to celebrate the brilliant and extraordinary backbone of the cattle industry in Northern Australia in the 1930s, and that is the indigenous stockmen,” he enthuses.

Martin’s production and costume design teams began the process of researching the very particular social history of the cattlemen of the era by studying various works of non-fiction and biographies such as Hell West and Crooked by Tom Cole, and Kings in Grass Castles and Sons in the Saddle by Mary Durack, which vividly describe the lives of the pioneering people who lived in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia at that time.

Interviews were conducted with veteran outback cattlemen, and the filmmakers consulted extensively with the owners of Carlton Hill Station, the property on which the film’s fictional homestead Faraway Downs was constructed. Luhrmann, Martin and their research teams made numerous field trips to the Kimberley region, as well as a visit to the Stockman’s Hall of Fame in far north Queensland, and the Northern Territory Archives.

Martin also utilized Picture Australia, an extraordinary online cache of digitalized images from libraries all over Australia, which includes the Durack Collection of photographs, an invaluable visual insight into the book series. This resource enabled Martin’s team to study thousands of scanned images not available in print.

“We needed to be clear and accurate about a lot of unusual detail from the history of this particular period,” Martin says. “We researched everything from the appropriate 1930s breed of cattle, the shorthorn, to what the cattle was worth and how the prices rose during the war years. We learned how much a drover would get paid, how many stockmen and horses he would need to deliver the cattle, and what a particular station’s brand looked like. We had to investigate the 1930s Australian stock saddle and tack and have them custom made for the actors by a saddle maker versed in the finer details of the period. The Australian stock saddle is designed to hold the rider securely over great distances and rough terrain. A lot of indigenous stockmen rode bareback and shoeless, but certain modifications needed to be made in translating this to film, either for character or safety purposes.”

Luhrmann’s research even extended to participating in an actual cattle drove. Along with associate producer Paul Watters and Luhrmann’s assistant, Schuyler Weiss, the director found himself on horseback, pushing hundreds of cows through the hot and dusty outback terrain.

At another point, as he was plotting his characters’ trek through the Northern Territory and the vast, unforgiving Kimberley, Luhrmann embarked on a private journey across the country to experience the land in a deeper, more personal way. He gained insight into the landscape and the people that proved to be more powerful and potent than anything he could derive from history books, and he encouraged Martin to take a similar trip – which she did, along with their two children.

“One of the reasons I started on this creative journey, what I sought to get out of it, was a more direct understanding of my country,” Luhrmann says. “I became deeply connected to the truth and realities of my homeland, its history and its people. Being in the cross-fire of these stories, while in the process of creating my own, has deepened my understanding of Australia immeasurably.”

About The Production

Principal photography on AUSTRALIA commenced on April 30, 2007 at Strickland House in Vaucluse, New South Wales. Production then moved to the shores of Bowen, Queensland, where production and costume designer Catherine Martin and her art department, headed by supervising art director Ian Gracie and art director Karen Murphy, constructed one of the film’s two massive exterior sets: the 1930s-era city of Darwin, a thriving tropical outpost in Northern Australia where Lady Sarah Ashley arrives and begins her tumultuous journey across the Outback.

“Bowen was the ideal location because we found two huge vacant lots located on the seafront by the wharf and, by some stroke of fate, the Darwin wharf and Bowen wharf face in the same direction, so we could match the light at both locations,” Martin says. The five-acre set, built over ten weeks, included a two-story pub, a Chinatown area, period telegraph poles and street lighting, dirt roads and extensive re-dressing of existing buildings to ensure these structures blended in with the fabricated elements. “At first we felt challenged by the fact that Darwin is on an escarpment and our Bowen set is flat,” says Martin. “However, this allowed us to condense all the elements of Darwin into a smaller geographical area, and still convey a sense of scale, depth and atmosphere in bringing the town to life.”

Filming in Bowen wrapped on June 28 and the production headed to the “Top End,” the northernmost part of the Northern Territory, to shoot in Darwin itself. Luhrmann utilized the unique tides along the wharf area for filming scenes of Sarah’s arrival in Darwin, as well as action sequences that take place in the aftermath of a devastating attack on the town by Japanese bombers.

After moving to Sydney for a few weeks of shooting on soundstages at Fox Studios Australia, the company traveled to the remote East Kimberley region of Western Australia, where production headquartered in Kununurra. Access roads were forged and country roads were graded so that huge containers of materials and supplied could be trucked into Carlton Hill, an isolated location 60 kilometers outside of Kununurra, where Martin and her team built Faraway Downs, Sarah’s ramshackle homestead situated on a sprawling cattle ranch in the middle of the vast, inhospitable wilderness.

Luhrmann, Martin and cinematographer Mandy Walker used a combination of digital technology and extensive location scouts at Carlton Hill to construct the perfect relationship between the homestead set, the landscape and the light. As Martin explains: “After finding the location, we had the environment scanned and we then built a digital model of the house, which we moved around until we found the perfect spot. This did not, however, excise the need for lengthy scouts to the actual location, where Baz paced out every scene to ensure the distances the actors needed to cover were dramatically correct. There is also a large Boab tree in the front of the homestead, which is a key element in the composition. We spent a lot of time spacing it out to determine how big the tree should be and how far away from the house it should be positioned.”

Martin relished the challenge of bringing Luhrmann’s vision of Faraway Downs to life. “I loved working with set decorator Beverley Dunn and our team to achieve the major textural changes the homestead undergoes from the dilapidated state we first see it in, to the green oasis it eventually becomes,” she relates. “The house had to be a character in both of its incarnations. It was logistically difficult to accomplish this transformation, but ultimately very satisfying.”

To underscore this transition, Walker infused scenes of Sarah’s initial arrival at Faraway Downs with dark, dusty red tones, and then shifted to a white, light and airy look as the environment changes in concert with Sarah’s transformation.

The filmmakers studied vintage color photographs from the 1930s and 1940s for inspiration as they collaborated on their overall color palette for “Australia.” “We wanted to create the period feel of a slightly de-saturated canvas containing bursts of color,” Martin says. “The environment in which we were shooting helped us enormously in this process, because the dirt on the ground wound up covering everything. Nature helped us form a muted background from which all these colors pop.”

Walker and her team were responsible for replicating the majestic colors and textures of the landscape on soundstages where Luhrmann could shoot coverage of exterior scenes in a more controlled environment. “We called it the `Lucas and Lean Approach’ to filmmaking,” Walker explains. “Baz would shoot these spectacular, David Lean-esque wide shots on location, and then we would come back onto the stage and do the `George Lucas’ part, shooting the rest of the scene against a blue screen or a set. We needed to take what was shot outside, match it, and then seamlessly combine the two. This was a huge challenge for us because the colors of the Northern Australia landscape are unique. So it was a great compliment when we would watch the footage and people couldn’t tell the difference between what we had shot on location and what we had done on stage.”

Hugh Jackman enjoyed the collaborative process that evolved out of Luhrmann’s shooting style, in which the actors might film close-ups for a scene three months after shooting accompanying wide shots on location. “It’s very much like working in the theatre because the scene sits with you, and you keep thinking about it and discussing with Baz, and it constantly develops,” Jackman observes. “A lot of directors get very afraid that things are going to develop, that things will be lost in rehearsal and they’ll never catch them on film. Baz is just the opposite. He loves the journey of discovery. He’s never afraid that because you had magic in the first take, you won’t have magic in the second. It’s such a joy to work with him because the craft of the actor is to keep exploring, to keep finding magic, and Baz has an uncanny knack of finding magic more often than most.”

Martin and her costume team, headed by wardrobe director Eliza Godman, faced the mammoth task of creating almost 2,000 costumes for the film – a scale four times larger than their work on “Moulin Rouge!” (Because 1930s vintage clothing proved too small for contemporary actors to wear, the costume department had to design and create 60 evening dresses for one scene alone.)

“What is interesting about Baz’s approach to costumes is that he is as focused on the texture of the background characters’ costumes as he is on Nicole and Hugh’s wardrobe,” Martin relates. “He is not satisfied with generic extras. Each role in every scene needs a specific look.”

Martin designed an extensive wardrobe for Lady Sarah Ashley, which reflects the character’s personal transformation as the story progresses. “Sarah is a very independent, capable, modern woman, and that spirit is expressed in her clothes,” Martin says. “She wears pants, which is very avant-garde, in the spirit of such forward-thinking women of the ’30s like Katherine Hepburn and Carole Lombard.”

Though she is fashion-forward, Sarah is very rigid and controlled. “Baz had strong views about the kind of graphic `Englishness’ he wanted for Sarah at the beginning of the movie,” Martin elaborates. “She arrives on the flying boat wearing a blue and white nautical outfit, which would have been more suitable for the Riviera than for 1930s Darwin. When she travels to Faraway Downs, she wears a pith helmet and gauzed netting as if she were on a safari in Africa. The idea was to keep her quite tight and restrained. There is a sense of formality and occasion every time you see her.

“When she gets caught in a cattle stampede and loses all her clothing, she loses her pretense. She makes the decision to choose survival over appearance and, in the process of pushing 1,500 head of cattle across the harsh terrain, she is transformed into a very different woman. After the stampede, we keep the characteristics of her wardrobe from the start of the film but simplify it to make it more real as the movie progresses.”

“I just put myself in Catherine’s hands and trust her completely,” says Nicole Kidman. “She’s already won one Academy Award, but she deserves to win many more because there are few people in this industry who are as abundantly talented as she is.”

Martin approached legendary shoemaker Ferragamo to collaborate on the design of Sarah’s shoes. “Ferragamo is synonymous with fame and fashion of the 1930s, and for revolutionizing certain styling and manufacturing techniques,” she says. “One of the quintessential Ferragamo traits is their confidence to mix often exotic materials with more luxurious fabrics. The showcasing of this trait and use of materials such as chagreen is a wonderful complement to the exoticism of Northern Australia during this period.”

Martin accessorized Sarah’s wardrobe with pearl drop earrings custom-made by Paspaley, Australia’s premiere supplier of south sea pearls of the period. Diamond jewelry designer Stefano Canturi created a suite of jewels for the character, including a diamond brooch, engagement and wedding rings, and diamond and coral earrings. Renowned fashion house Prada, a favorite of royalty and aristocracy of the 1930s, supplied Sarah’s suite of blue and white luggage.

To draw inspiration for the costume designs for the Drover and the film’s 200 stockmen, Martin poured through the archives at R.M. Williams (`The Bush Outfitter’), a company established in 1932 that is known for manufacturing traditional clothing of the Australian bush.

After determining which style of dress was appropriate for each stockman character, Martin had the patterns cut by the film’s wardrobe department and graded before turning them over to the R.M. Williams work rooms, where the majority of cattlemen’s costumes and boots were manufactured. (Existing styles of R.M. Williams boots, as well as all manner of footwear and leather goods revived by the company for Martin, were used in the production.)

Hugh Jackman’s costumes are derived from the traditional garb of the Australian `drover’ – a mixture of moleskins, checkered shirts and R.M. Williams boots, topped off with an Akubra bush hat.

Jackman trained for a year in the style of horseback riding particular to stockmen like the Drover, who is known as a superlative horseman. “While I had ridden before, it took me about nine months before I really enjoyed it,” he confesses. “It takes a while to give your trust over to that horse. But when the horse feels it, he’ll give over to you too and it’s a really beautiful kind of relationship. Learning to ride has been one of the great joys of doing this movie. I’m absolutely hooked for life now.”

Martin and company devoted a great deal of effort to the research and creation of wardrobe for the film’s Indigenous characters. As she explains, “In the film we represent two distinct Indigenous groups: a Kimberley mob, who are the traditional owners of the land on which Faraway Downs is built, and an Arnhem Land mob. We decided, in consultation with the Miriwoong tribe, the actual traditional owners of the real-life Carlton Hill station, to represent these groups as pan-Kimberley and pan-Arnhem Land, even though the cultural practices of groups within these broad geographical areas vary greatly.”

“Each indigenous character has a very intensely studied costume based on interviews, expert advice and photographic research, particularly the photos of Donald Thompson and Baldwin Spencer who documented the lives of the Indigenous people of the Top End in the 1930s. We were also greatly assisted by Indigenous body adornment expert Dr. Louise Hamby, Postdoctoral Fellow of the Research School of Humanities at the Australian National University, who is also an expert in the Thompson photographs. The idea was to challenge people’s stereotypical views of what our Indigenous people looked like in the 1930s and celebrate the artistry and beauty of the traditional dress of that area.”

After shooting AUSTRALIA across four states and vast distances from one end of the continent to the other, the filmmakers, cast and crew developed a new appreciation for the mystery and magic of the country’s landscape. “During our days in the Kimberley, we’d be shooting in this extraordinary heat and asking ourselves, `Can we really go on?’” Luhrmann recalls. “But every sunset brought a transformation from brutality to beauty. When the stars come out and the air cools, you forgive it all and it fills you with life. It’s like you’re in a dream.”

“I’ve seen far more of this country during the making of this film than I had in the 30 years that I lived here,” says Kidman, who had never been to the Northern Territory before. “Even though it was extremely difficult at times, I’m so glad we traveled and filmed in these locations. To feel the air and be ravished by the elements was exquisite and necessary.”

“It really changes you,” Jackman agrees. “It changed me. Like many people, I was born and bred and have lived most of my life in the city. This film gave us the chance to open our eyes and our hearts, and to really see this amazing country. The diversity of it. The vastness of it. The longer you spend here, the more it seeps in. It’s very powerful and humbling at the same time.”

Production notes provided by 20th Century Fox.

Australia

Starring: Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman, David Wenham, Jack Thompson, Bryan Brown

Directed by: Baz Luhrmann

Screenplay by: Baz Luhrmann

Release Date: November 26, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for some violence, a scene of sensuality, and brief strong language.

Studio: 20th Century Fox

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $32,936,547 (77.0%)

Foreign: $9,850,878 (23.0%)

Total: $42,787,425 (Worldwide)