About the Film

The extent to which I never asked him questions is astonishing in retrospect – I blame Albert Camus…One of the rules of existentialism as practised by me and my disciples at Lady Eleanor Holles School was that you never asked questions. Asking questions showed that you were naïve and bourgeois; not asking questions showed that you were sophisticated and French. I badly wanted to be sophisticated. Lynn Barber, An Education

“I’m still not entirely sure what it was about Lynn Barber’s piece that had such a strong pull on me, but quite clearly there was one,” says screenwriter Nick Hornby. “I read it and gave it to my wife, Amanda Posey who is one of the producers, saying, ‘Look, there’s a film in here.’ She agreed and with Finola Dwyer, her fellow producer, started thinking about writers. I was aware that I was becoming envious – ‘what do you want that loser for!?’ – that sort of thing. So I said I wanted to have a go at it.”

“I always thought I must remember at some point to write the whole story of my first boyfriend as I always thought it was extraordinary,” says journalist Lynn Barber of her brief memoir. “The only person I’d told was my husband because it was such a long and complicated story – you couldn’t really just tell someone casually over dinner or something. It was almost like a secret I’d been carrying around with me.”

“Perhaps what drew me to the piece most of all was that Lynn Barber has a very strong, sometimes confrontational voice in her profiles so when I saw that she’d written about her early life, I thought, Ah, I’d like to know about that!” says Hornby. “People who read her have interest in her, but Lynn has always kept herself out of her journalism and I was fascinated to find out about this story.”

Hornby continues: “It was always going to be a long shot – adapting 10 or 12 pages in a literary magazine – but it really was a labour of love. I felt that I understood Jenny’s life; I was a suburban boy and my parents didn’t go to university. I liked the richness of the dilemma which is, in some ways, ‘life vs. education’. I was convinced that I could write a screenplay that would amplify Lynn’s piece and make it interesting cinematically.”

Describing the period in which AN EDUCATION is set, all of the filmmakers are quick to point out that Britain hadn’t actually started swinging in 1961. Four years on from Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s claim that ‘most of our people have never had it so good,’ the average English family continued to lead buttoned-up, thrifty lives. Preoccupied as they were with changing social and sexual mores, most people were in no hurry to embrace them.

“Every time people talk about the Sixties, I want to scream,” says Barber. “The Sixties didn’t actually start until around ’63 or ’64. It was still pretty drab before that.” Hornby quotes Philip Larkin’s, ‘Annus Mirabilis’:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three…

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

“For me, one of the points of the film and one of the attractions of the setting was that in 1962, we were still stuck in post-war austerity Britain,” says Hornby. “At the time, England was an extremely insular country, quite a poor country. The Second World War made America, and their ‘50s – those big cars and the rock ‘n’ roll – were a product of doing well. Over there, it was all about Cadillacs. Here in Britain, we were still waiting for a bus.”

“I previously made a film which took place in Denmark in 1957 so I know something about the fear of excess, the shadow of the war and the very simple fantasy lives that people led then,” says director Lone Scherfig. “But of course, I didn’t know London so I was cautious, careful to get everything right. I was watching carefully to make sure that anyone who wasn’t English or from Twickenham or 16 years old in 1962 could understand what was going on. We tried to really get the flavour of the time because, to a certain extent, we all believed that the story could only take place then if audiences were expected to identify with it now.“

“It’s very hard for us now to realise how close together things happened. If you look back from now to the late 80s, for example, it seems incredibly recent times to those of us of a certain age,” says Hornby. “That’s the distance between this period and the beginning of the Second World War. We had rationing into the mid-50s; it was very hard to travel abroad because of currency regulations, very little variety of food was available – there were so many things we didn’t have in this country.”

Carey Mulligan who stars as suburban schoolgirl Jenny recognises that the journey of her character, although based on Barber’s real-life experience, can be seen as a metaphor for the period: “As well as being a coming-of-age story for Jenny, it’s a coming-of-age story for the Sixties,” she says. “Everyone said, ‘Oh, you’re doing a Sixties film!’ I said, ‘No, it’s not flower power and stuff; it’s before that.’ So they said, ‘What happened before that?’ And I replied, ‘Not much!’”

“Jenny’s parents, Jack and Marjorie, are very much a product of their time,” says Hornby. “But Jenny is just beginning to chafe against it and David is the perfect conduit – somebody to lead her out of the ‘50s and into the ‘60s. It’s almost as if the ‘Swinging Sixties’ are arriving in Jack and Marjorie’s kitchen in Twickenham a few years before they arrive in anyone else’s,” says Hornby.

“We’re right at that moment when the door is just being pushed open,” says designer Andrew McAlpine. “We’ve stopped having to use coupons and we’re just starting to become ourselves again. The mum and dad in our film know something is about to change but they don’t know what it’s going to be; they use their daughter as a conduit to understanding the future.”

“The mentality of the time was very Cold War, trapped in a rather narrow view of life: work, home and that was it,” says Alfred Molina who plays Jenny’s father, Jack Mellor. A minor civil servant whose admirable ambition to better his daughter’s life has become an all-consuming obsession, Jack was raised in the belt-tightening years immediately after the war and he struggles to emerge into a new era.

“Everything was grey,” says Molina. “And then, into Jack’s monochromatic world comes this rather exotic figure, David. It’s a bit like a pigeon coop into which a peacock suddenly arrives, this colourful, slightly scary figure.”

“To me, beginning around the time of the arrival of the Pill, it’s as if a bowstring has been pulled all the way back, preparing for an explosion of everything that’s been pent up for so long,” says American actor Peter Sarsgaard who plays David, Jenny’s older suitor. “The people are starved for fun and loads of them are about to have it. And they are going to have it without caring about any rules. There’s something about David that’s like that – he needed to have waited about eight years and then he would have had tons of fun.”

“The way that the character of David was originally written about in Lynn’s piece, it would perhaps have been harder to persuade a cinema audience that this was a relationship that made sense,” says Nick Hornby. “Quite rightly, Lone wanted to soften that relationship, to take some of the edges off David and make a proper connection between the characters in a way that would sustain an audience’s attention and sympathy.”

“Each actor is in some ways the lawyer for their character – they see the script from their point of view,” says Lone Scherfig. “My job is to see that but also to see it from the audience’s point of view.”

Sarsgaard was able to leave aside any judgement of his character and his actions. “When David is with Jenny, it’s as though he were experiencing everything for the first time again – ‘It IS a nice car, isn’t it? Paris IS a great city, isn’t it?’ It’s not about sex, it’s about life. He’s not a pervert; he’s just a guy who wants to live life to the most.”

“Peter has a lovely, childlike quality as David,” says co-star Dominic Cooper who plays David’s friend and business partner, Danny. “He’s kind of giggly. There’s a hint of menace but mostly, he seems to be a completely trustworthy, very giggly guy.” Peter Sarsgaard and Carey Mulligan decided that he would have to charm her into the car in the scene of David and Jenny’s first meeting; she would not do what was written for her character in the script unless he actually succeeded in persuading her to do it. He did.

“David is very seductive in a subtle way and part of my job was to seduce the audience the way he seduces Jenny,” says Lone Scherfig. “If you knew what was happening behind his very nice façade, the story would be too predictable. You have to feel for him, you have to like him. I found him very interesting and the worse he got, the more I liked him.”

“I liked the idea that David is a taste of things to come,” says Hornby. “He is the product of a classless society, in a way. He wants the good things in life, not just money and being flash; he’s interested in what’s going on – he wants to listen to music, to read, to watch movies. I think he’s more switched on than you might think at first glance.”

“David not only tests the parameters of Jenny’s father’s life but also his prejudices,” says Alfred Molina. “There was a great deal of racism in post-War British society which permeated through all the classes – it wasn’t just upper class twits, it was everybody. Despite the horrors we were aware of by then, of what had happened in the camps in Europe, there was still a huge amount of anti-Semitism in Britain. And all of these things get touched on in Nick Hornby’s script – everything is placed in context.”

“Playing this man who feels like an outsider, someone who is pretending to be someone they’re not, that’s exactly what I was doing the whole time on set,” says Sarsgaard. “I was trying to do exactly the same thing my character was trying to do: pass myself off as someone else.”

Costume designer Odile Dicks-Mireaux took a lot of inspiration from films of the period and the role model for David’s wardrobe was the star of the 1962 hit Dr. No, Sean Connery, in the very first James Bond film. “It seemed like a new look of the time, coming out of the ‘50s into this very ‘60s look,” she says.

For Carey Mulligan, 22 years old at the time of shooting, the idea of playing a 16 year-old initially inspired a degree of panic. “I was worried about coming off as a 22 year-old just pretending to be a teenager. Then I thought about what I was like at 16 and I really wasn’t that different. I imagined that I’d had had a higher voice and been really giggly all the time, but I wasn’t. The only thing that changes between being 16 and being a little bit older is that when you’re younger, you don’t realise that you can hurt people by what you say and you’re less able to put a lid on things; you’re less able to measure yourself.”

“Carey is spooky,” says Nick Hornby. “I hadn’t seen her and Finola said they were going to cast this girl Carey Mulligan. I said, how old is she and they said 21 or 22 and I was like, oh, okay, that’s it then, you’ve ruined the whole thing because she’s supposed to be 16. I can see why you’d do it but it’s not going to work. And then when you see her in the schoolgirl scenes, you think Hey! You can’t have someone sleeping with her! That’s indecent! It’s sort of freakish that she’s able to play a 16 year-old girl and you never doubt for a moment that she is that age. And yet, with a bit of makeup and a different hairstyle, she becomes Audrey Hepburn.”

“Jenny’s is a big journey with a lot of changes,” says Odile Dicks-Mireaux. “She’s got to look 16 or 17 in a school uniform, so that’s one look you have to achieve. Then you’ve got to get from that point to the point where she is transformed by Helen. The first transition was the hard one – the school uniform wasn’t difficult to do. But how far do you go to convince everybody that she is looking very different, but she is still a very young girl?”

Mulligan found that the return to wearing a school uniform and filming in a classroom helped her not only to look like a teenager again, but to think like one, too: “I felt horrid in the school uniform; the crew started treating me like a 12 year-old,” she says. “They actually stopped swearing in front of me. During a scene in the classroom, I started to think ‘God, this is SO boring!’ I realised just in time that I’d fallen back into schoolgirl mode and I needed to snap out of it.”

Jenny’s transition from bored teenager to (almost) credible grown-up is encouraged by Helen, the gorgeous, dippy girlfriend of David’s business partner Danny. “I think when meeting Jenny, Helen thinks oooh, good! another puppy for me to play with!” says Rosamund Pike. “I think she’s a very affectionate sort of person but Helen’s protective only as far as giving sartorial advice is concerned; she will protect anyone from looking too awful at a party but I’m not sure she would protect anyone from having unprotected sex, for example.”

In her original article, Lynn Barber describes being in love with her suitor’s friends as much as – if not more than – she was with him. “Danny and Helen are crucial for Jenny,” says Nick Hornby. “She’s seduced by three people. She’s obviously seduced by David but the thing that tips her over the edge is getting to hang with Danny and Helen in their home, surrounded by their beautiful things – he’s got his Lockey Hill cello and his paintings and Helen’s got her beautiful clothes; she even gives some of them to Jenny. This is why Jenny ends up taking such a risk with her own life. It’s impossible to overstate the pivotal nature of the influence that Danny and Helen have.”

“It happens over and over again,” says Dominic Cooper. “We can all put ourselves in Jenny’s position. When you’re growing up, you get led astray, misguided, involved in things that you shouldn’t get involved in. You forget about what’s important in your life. I think all of this is very relevant. I completely understand being drawn into something that you’re not quite part of and finding it thrilling.”

“A lot of people reading the script for the first time responded to the betrayal – the idea of being misled by someone who turns out to be other than they originally seemed,” says producer Amanda Posey. “We thought from the outset that it was a universal tale.”

“I never got into the situation that Lynn Barber or the Jenny character gets into,” says Olivia Williams, who plays Jenny’s English teacher and mentor, Miss Stubbs. “But a girlfriend and I used to go out together and pretend we were much older than we were. We’d go out drinking and dancing with men in their early 30s. Looking back, you have to ask yourself: what were they thinking? What were they doing with girls who were clearly 16?”

“Amanda and I exchanged experiences we’d had with older guys when we were at school,” says producer Finola Dwyer. “The more we talked about it, the more we discovered that almost everyone has some such experience including men sometimes, with older woman. I think it is universal, when you are young, to want something other than what you have, to escape what seems like a boring existence and meet someone glamorous and funny who turns you on to another world.”

Lone Scherfig is in no doubt that Jenny drives the drama. “She’s not really a victim of anything except for the fact that she is so much younger than David so he really should be the responsible one,” she says. “But Jenny tastes blood – she is part of what is happening and she does turn 17 in the story so it’s not like she’s a child. But she is innocent; the story is about her loss of innocence and David is the villain – I have to remind myself because I like him so much.”

“All the young girls we auditioned loved the script and most of them had their own stories to tell, often to the surprise of their parents,” says Finola Dwyer. “I was always taught that in film, a child’s coat getting torn is as significant as 500 soldiers get killed – it’s all a matter of which scale you weigh things on,” says Scherfig. “Hopefully, this film is as moving as one in which something much more drastic happens because for Jenny, it’s a major turning point in her life. I hope that not too many people have experienced what she has to experience in the film but I think the audience will identify with it.”

“Lynn Barber was involved and supportive throughout but at a certain point, she seemed to decide that she trusted us to get on with it and she let go,” says producer Amanda Posey. “She actually said that, on watching the film for the first time, she became so involved in it that she wanted to know what happened at the end. She had quite forgotten that it was her own story.”

Production notes provided by Sony Pictures Classics.

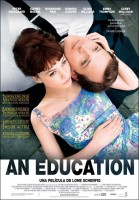

An Education

Starring: Peter Sarsgaard, Rosumund Pike, Emma Thompson, Olivia Williams, Carey Mulligan, Dominic Cooper, Alfred Molina, Sally Hawkins, Matthew Beard

Directed by: Lone Scherfig

Screenplay by: Nick Hornby

Release Date: October 9, 2009

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for mature thematic material involving sexual content, for smoking,

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $8,676,082 (81.1%)

Foreign: $2,023,562 (18.9%)

Total: $10,699,644 (Worldwide)