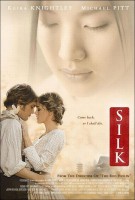

Based on the beloved, best-selling novel by Alessandro Baricco, “Silk” is the story of Herve Joncour (Michael Pitt), a 19th Century French silkworm merchant who travels to Japan and begins a clandestine and forbidden romance with a mysterious and sensual woman.

Silkworm eggs. In one’s palm one could hold thousands of them. When the pébrine epidemic-the spotted silkworm disease that ravaged eggs from European hatcheries in the 1860s-spread overseas, however, eggs from as far away as Africa and India became infected and the entire European silk trade seemed doomed.

To continue his lucrative trade Baldabiou (Molina), a roguish French trader, decides to send a young military officer Herve Joncour (Pitt) on a perilous mission to Japan. Thus, separating him for months on end from Helene (Knightley), his lovely and devoted schoolteacher wife. The island that produced the finest silk in the world for thousands of years, prior to the opening of the Suez Canal, Japan was considered a dominion forbidden to foreigners, quite literally the opposite end of the world.

It is here that Herve encounters the powerful and feared local baron, Hara Jubei (Yakusho), with whom he will trade for the precious silkworm eggs. And it is here, in a world unlike anything that Herve has experienced before, that he becomes entranced by the baron’s concubine, a deeply mysterious girl of intoxicating beauty. Without speaking one another’s language, together they share a doomed, obsessive love…

A film of painterly beauty and ravishing romance, “Silk” is a historically rapturous epic romance of East meets West. “Silk is a short novel that you can read in just a couple of hours,” begins co-producer Nadine Loque of author Alessandro Baricco’s sweeping romantic epic from 1996, an internationally best-selling phenomenon that has been translated into 26 languages. “But what’s fascinating about it is there’s a big story in this short book, written in very spare, poetic language. And the challenge was how to transpose that story—which is told with such a stunning lightness of touch—into film.”

“The Red Violin was a great film to make because we got to travel to all those places and live through this beautiful object that had seen so much,” says producer Niv Fichman, weaving a worthy line of continuity between Girard’s films. “And in a way Silk is an extension of that: it’s about an explorer, a traveler who is an observer who takes in everything around him. He respects everything that he sees and he doesn’t try to change or dominate it, he just tries to take it in and understand it.”

“It’s a period story but it goes way beyond any period,” says writer-director Girard, who has directed Baricco’s work once before, having staged the author’s play, Novecento in Canada and at the Edinburgh Festival in 2002. “It talks about us, about relationships and the complication of how people live their relationships. And I think it’s a very rich, cinematic story in that regard. On the one hand, it provides the intimacy of the love story between Herve and Helene and the obsession he nourishes for the Japanese girl. Most of the story is very private and intimate. And at the same time it has the epic quality of this grand journey from France to Japan in the mid-19th Century.”

Weaving Silk

“Well, I couldn’t imagine the challenges involved in adapting a novel as beautiful, as poetic, as Silk,” begins co-writer Michael Golding. “Usually when you think about adapting a novel it’s about what you are going to remove, because it would be 12 or 20 hours long if you film the whole book. Silk is a different story. I feel that the book is like a series of beautiful miniature impressions, tiny little perfect mosaics that miraculously add up to a very strong emotional punch.”

If Baricco’s source material is something of a prose poem, one that at first glance might appear immune to translation into other mediums, it is also a story rich in cinematic contrasts: East vs. West; the fragility of silkworm eggs vs. the mighty textile industry they drive; youthful inexperience vs. swashbuckling leaps into the unknown; epic journeys over land and sea vs. the most intimate revelations of the heart.

“There’s not a bone in my body that would wish to betray the novel, and yet one has to—I wouldn’t say ‘translate’ I would say ‘transform’—the novel into something that works in a different medium, and that’s the challenge,” says Golding. “Movies are stories and there has to be a strong narrative thread. So how do we tell the story? What do we move to the foreground and what do we leave subtle and invisible in the background? And I think one of the things that was most important to bring up was Helene, because she’s such a shadow in the book, and she proves to be so important, and part of her power is that she’s been there all along.”

Helene’s Garden

One of the great achievements of the adaptation process came in the development of Helene, Herve’s resolutely faithful and supportive wife, who in very important ways, holds the key to the mystery at the heart of the story. While in the novel Helene exists as a somewhat recessive, shadowy figure, the visual concretization of the film medium demanded her character be fleshed out to a much more significant degree. And, in Keira Knightley, the filmmakers were blessed to have a talented young actress whose relatively limited screen time would suggest volumes.

“I’m a huge fan of the book,” says Knightley, an audience favorite from her work in the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy and Academy Award-nominated work in the adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice. “It was given to me years ago by a friend and it was one of those things where a group of us all passed the book around and got absolutely obsessed by it. And in the book, Helene is nearly see-through. She’s mentioned quite a lot but never in any great detail. And it’s been quite interesting trying to develop this character. I like the idea of playing someone who keeps a lid on her emotions, who doesn’t go shouting everything out. I think I’ve played a lot of roaring women, and I really wanted to play one that was quieter and more internal.”

Filling in what Baricco intentionally elided, the screenwriters provide Helene with a vocation as well as having her be the prime mover behind one of the film’s most auspicious visual coups: a flower garden worthy of Monet. “We needed to make a number of changes, such as giving Herve’s garden to Helene so she has her own world,” says Girard. “We also needed to turn her into a schoolteacher so she has a life when Herve is gone and so on. I would say that was our main battle, draft after draft, to look again and again how to turn Helene into a full-blooded character.”

Indeed, if Helene remains, as producer Loque describes, “a rather distant player in this game,” she holds the key to the film’s O. Henry twist of an ending, a resolution which forces the viewer to reconsider everything that has come before. “Both Michael and François said they found Helene the most difficult character,” says Knightley. “I’m fascinated by what she doesn’t say. And I think the most beautiful and tragic thing about Helene is that you don’t really understand her until she’s dead, until Herve finally understands her.”

Agrees producer Fichman: “The most crucial point that all of us felt had to be addressed was that in a modern movie you really can’t have a woman who just stays behind and supports her husband no matter what, even though she suspects she’s being betrayed, it just didn’t seem right for us to do that. So we worked really hard on expanding the character and making Helene into a much more complex and strong character.”

Silk’s other estimable cast members suggest the truly international nature of this Canadian- Italian-Japanese co-production. “We have the best possible Herve in Michael Pitt,” says Girard of the actor familiar to audiences from his work in Gus Van Sant’s Last Days, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village, Larry Clark’s Bully, and John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch. “He’s got the perfect sensibility. The first meeting I had with Michael I couldn’t believe how close he was to the character in age, looks, and attitude. Michael is not a big talker, he takes his time before answering or commenting on a remark, which is very much how we envisioned Herve.”

Says Pitt of Herve, a character who exists largely as an observer, one whose greatest passages of dialogue occur as reflections, in voice over: “The challenge is he’s not a very external character and sometimes it can be harder to play that. It’s easier when you’re yapping because you have something to say. It can be more difficult to say things without saying things because people don’t notice it as much.”

Playing the pivotal role of Baldabiou, an entrepreneur who seeks to revive the town’s waning fortunes by reopening its shuttered mill, is Alfred Molina, an actor equally at home in art house films, summer blockbusters, and the stage (The Hoax, Frida, Chocolate, The Da Vinci Code, Spider-Man 2, and the recent Broadway revival of Fiddler on the Roof.) “Baldabiou is a man who doesn’t seem to come from anywhere in particular, he just sort of arrives,” explains Molina. “He’s a puppet master in a sense. He doesn’t have the usual sort of respect or cow-towing to authority as everyone else does. And what he brings to the story is he’s the catalyst for the adventure that Michael’s character, Herve, will go on.” Says producer Loque: “Alfred is like a magician. He’s a greater-than-life character and there’s no one else in the world that could have played the role. He’s a dream come true.”

One of Japan’s most celebrated and charismatic actors, Koji Yakusho is a favorite of his country’s top filmmakers and a nine-time nominee and two-time winner of the Japanese Academy Award. Yakusho is perhaps best known to western audiences for his performances in the original version of Shall We Dance?, Memoirs of a Geisha, and most recently for his performance in Alejandro Gutierrez Inarritu’s Babel. “Koji is just a superb actor,” says co-screenwriter Golding. “He brings so much to the role; he just walks onto the screen and there’s a weight and depth in who he is. If we shot this on a back lot in Los Angeles, it simply wouldn’t be the same.”

For the crucial role of the deeply mysterious and intoxicating Girl, Girard discovered alluring newcomer Sei Ashina after considering thousands of candidates in Japan. “I’ve never interviewed so many actors or actresses for a part as I did for the role of The Girl in Silk,” says Girard. “But when I met Sei I knew I had discovered something that was so difficult to find, which is that balance between great beauty and inner depth. The Girl must not only be beautiful… she has to be engaging in a very deep way, and that quality is what I found in Sei.”

“A Japanese Brigadoon”

Journeys by carriage, train, horseback, foot, and ocean. Passages cross the Alps and Ukrainian Steppes. Blindfolded voyages aboard a smuggler’s ship. French gardens and factories. An entire 19th century Japanese village… If finding cinematic analogues for Baricco’s spare, ethereal prose proved one challenge for the makers of SILK, concretizing those visual images proved another.

For the village of Lavilledieu and other neighboring French locales, the production company employed numerous locations in Italy, including Sermoneta, Ronciglione, Vicarello, Pigna, and Rome. “What made shooting in Italy possible for us is that we found a great village called Sermoneta that’s about an hour-and-a-half outside of Rome,” explains Production Designer Francois Seguin. “Sermoneta is a kind of unrestored stone village that has a little piazza that opens up enough for us to build this kind of French square.”

For the Japanese village that exists “at the end of the world,” the decision was made to build an entire village on location in Japan. “The European sets are more my own world, it’s a language I know architecturally. But the other half of Silk represents my first real contact with Japanese culture, and I was lucky to find great collaborators,” says Seguin. “The biggest set in Japan is the village, which doesn’t really have a name. It’s huge. It’s like a Japanese Brigadoon.”

Constructed near the small city of Matsumoto in Nagano Prefecture, embedded in the stunning “Roof of Japan,” Hara Jubei’s village was designed by Seguin and built in its entirety by Japanese Art Director Fumio Ogawa utilizing some sixty Japanese craftsmen and artisans. Extraordinary natural backdrops were also ultilized in the mountains, forests, and volcanic hot springs of Matsumoto, with additional filming taking place in Sakata City, on the Sea of Japan, at the mouth of the Mogami River in Yamagata Prefecture.

The construction of the unnamed village took two months and included a dozen structures. “Every building has windows, sliding doors, everything is very practical,” says Seguin. “Of course the insides of the buildings are incomplete, but the extras can go anywhere in the village, open doors, go inside, peek in, it’s a really beautiful set.”

The meticulousness of the production extended to the costumes, which bridge cultures and continents as delicately as the film’s title suggest. “We never see in the movie a scene with a thousand extras,” explains Costume Designer Carlo Poggioli. “But when you put it all together, we have something like 2,000 costumes.”

If Silk is an intimate-feeling epic that boasts a painterly visual style, it is also something of a memory piece, something told (Herve narrates the entire film in an extended flashback), a story that insists on the bonds between slowness and memory.

“I’ve never worked with a filmmaker who keeps saying, ‘Slow down, take your time over a scene,’” says Knightley. “Normally directors say, ‘Speed up, take out that pause, come on, quickly, quickly, let’s go onto the next one.’ And François is all about movement and slowness and that’s a wonderful thing.”

“The way Baricco writes and the way that François shoots are very similar,” says Poggioli. Agrees Molina: “He’s interested in beauty, he’s interested in the vulnerability of things.” With Silk, Girard and company have created a work as shimmering and strong as the material of its title and the prose from which it is inspired. “It’s a good name for the novel and the film because both are very dreamlike,” says Pitt. “Everything flows into each other.”

“I think we need more beauty in cinema,” says Golding. “Our world is getting harder. The world is rough and the images, especially the last couple of years, have been very rough, and I don’t want to shy away from that. I want to embrace that but I also, as a moviegoer, want beauty. I don’t want beauty to be simply about surfaces; I don’t want it to be pretty just for the sake of being pretty. When you have a deep story, and you can reveal it in beautiful images, I think that gives something that the world is hungry for. And I think François is just a master of this kind of cinematic storytelling. Just watching him frame shots and watching the composition of shots, is very thrilling.”

Production notes provided by Picturehouse.

Silk

Starring: Keira Knightley, Alfred Molina, Michael Pitt, Koji Yakusho, Sei Ashina, Mark Rendall

Directed by: François Girard

Screenplay by: François Girard, Michael Golding

Release: September 14, 2007

MPAA Rating: R for sexuality and nudity.

Studio: Picturehouse

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $1,103,075 (14.1%)

Foreign: $6,698,982 (85.9%)

Total: $7,802,057 (Worldwide)