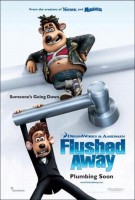

Tagline: Someone’s going down.

From DreamWorks Animation and Aardman Features, the teams behind the Oscar-winning hits “Shrek” and “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit,” comes the computer-animated comedy “Flushed Away.” Blending Aardman’s trademark style and characterizations with DreamWorks’ state-of-the-art computer animation, the film marks a unique new look for the artform.

In this new comedy set on and beneath the streets of London, Roddy St. James (Hugh Jackman) is a pampered pet mouse who thinks he’s got it made. But when a sewer rat named Sid (Shane Richie) – the definition of “low life” — comes spewing out of the sink and decides it’s his turn to enjoy the lap of luxury, Roddy schemes to rid himself of the pest by luring him into the loo for a dip in the “whirlpool.” Roddy’s plan backfires when he inadvertently winds up being the one flushed away into the bustling world down below.

Underground, Roddy discovers a vast metropolis, where he meets Rita (Kate Winslet), a street-wise rat who is on a mission of her own. If Roddy is going to get home, he and Rita will need to escape the clutches of the villainous Toad (Sir Ian McKellen), who royally despises all rodents and has dispatched two hapless henchrats, Spike (Andy Serkis) and Whitey (Bill Nighy), as well as his cousin — that dreaded mercenary, Le Frog (Jean Reno) – to see that Roddy and Rita are iced… literally.

Plumbing Together

After achieving success with the critically acclaimed box-office hit “Chicken Run” and the Academy Award-winning “Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit,” DreamWorks Animation and Aardman Features team up for the third time with “Flushed Away.” For this film, the two studios took their collaboration to a new level: after being conceived at Aardman’s UK studio, “Flushed Away” became the company’s first computer-animated film and was produced entirely at DreamWorks’ animation studio in Glendale, California.

According to director David Bowers, the movie reflects the best of what each studio has to offer. “We have Aardman’s charm and rich sensibilities, and all the imagination and technological capabilities of DreamWorks,” Bowers attests. “I don’t think the movie could have happened without either studio.”

As “Flushed Away” was in its early stages of development, the filmmakers realized their third collaboration would need to be entirely computer-animated for several reasons. Water is notoriously difficult to recreate in stop-motion, and the sets would have to be enormous to be in proportion with Roddy, Rita, and the rest of the “Flushed Away” characters.

According to director Sam Fell, Aardman had been looking to make a CG animated film for some time, and “Flushed Away” seemed to be the right project to make the jump.“We wanted to create a whole city, a whole world, and populate it with thousands of little rats walking around along canals instead of streets,” says Fell. “With water, crowds, big scope, many sets – it seemed like CGI could really help us make that happen.”

Bowers agrees. “The Kensington apartment, where the movie begins,would have had to have been full size,” he says. “There just wouldn’t have been room in the studio to do it. And there wouldn’t have been enough plasticine or clay in the world to do it.”

“At first, we thought we would do a stop-frame film with a lot of CG enhancements,” says Aardman co-founder and producer David Sproxton. “But when we looked at how much we would be doing on the computer – the extensive tunnels, the large sets, the water – we thought,‘Why not make the whole thing in CG?’”

In addition to the scaling challenges, the myriad water effects – critical components to a story set largely within a sewer world – provided an even more convincing case for CG. From Roddy’s titular tumble into the toilet’s whirlpool to the frenetic boat chase leading up to the film’s climax, water would need to be as versatile as the characters themselves.

Aardman co-founder and producer Peter Lord explains,“Water is practically a character in this film, and it’s just the hardest thing to do in stop-frame animation,” he says. “When we do water, it’s normally little bits of cling film making a splash, or animating drips of glycerin trickling down the damp character. To have a boat bobbing about on a stream or tearing along at a super speed, through a river, chased by villains on egg whisks – it would have been impossible.”

Head of effects Yancy Lindquist comments, “We have flushing water. We have water running down pipes. We have frozen masses of water. Each of those requires a slightly different technique.”

Like the directors, Lord says that “Flushed Away” remains a film that could only have been made by a collaboration between Aardman and DreamWorks. “I think ‘Flushed Away’ brings a stillness to the CG art form,” Lord says. “We believe in performance above all; the audience needs to believe in the characters. That often means watching what happens on the face when the character is almost still. That subtlety is what we do best. On the other hand, computer animation is great for big action. By putting the two together, we’ve got strong, believable characters and some truly spectacular action sequences.”

Visual effects supervisor Wendy Rogers expands on the idea of stillness: “We really have treated the characters as though they were puppets, and they’re animated to move that way,” she says. “We don’t have any dynamic simulation on the hair. Their clothing doesn’t flow when they walk. They’re hitting that pose and holding it rather than sort of easing through a motion.” While the film is set primarily in a fanciful underground world, the real life lessons are unmistakable.

Thrust together in their efforts – first to escape The Toad, then to put a stop to his dastardly plan – Roddy and Rita learn to rely on each other. “More than anything else, Rita wants to help her family,” producer Cecil Kramer says. “But she needs to learn that she can’t do that alone. When she opens herself up to accepting Roddy’s help, anything is possible. And Roddy’s journey is universal. You can have all the toys in the world, but they’re not worth much if you have no one to share them with. At the end of the day, we all need friends and families to connect, even the finest possessions pale in comparison to our relationships with others.”

Dual Diligence

From the characters themselves to the sets and backgrounds, Aardman films have a distinct look and feel – a style the filmmakers wanted to continue in “Flushed Away.” Because stop-motion technique itself is so integral to that style, bringing the Aardman look to CG required unique character design, careful attention to detail, and ultimately, a little restraint. The filmmakers knew they wanted to retain the patent Aardman characterizations in CG, but they were also determined to avoid direct replication of the clay figures into computer models. In combining the advantages of computer animation with the corporeal quality of stop-motion, they created something new – an evolution of the Aardman style.

“There’s definitely a look to the design of an Aardman stop-motion film,” asserts Sproxton. “There’s a texture that’s inherent in model work – the fingerprints on the clay, the wood grain, the plaster, the paint. You get a lot of texture simply because the sets and characters are constructed from real materials. That look is distinctly Aardman. I would say it’s our trademark.”

“We worked hard to translate the stop-frame style into the computer animated technique,” Fell states. “We wanted to use the CG technique to capture the signature Aardman warmth, charm, and tactile feel. It’s the best of both worlds, really.”

In a stop-motion film, Aardman artists create plasticine models with metal armatures. Stop-motion animators pose the characters’ bodies and sculpt their faces frame by frame. As a result of this painstaking process, the characters hit poses very quickly and communicate largely through facial expressions.

As Jeff Newitt, head of character animation, explains, the creators of “Flushed Away” found themselves freed by the new boundaries of CG, but constantly kept in mind the goal of matching the Aardman style. “The stopmotion armatures are restricted by gravity, and the weight of the clay or rubber or foam used in building the puppets,” Newitt says. “So when you animate them, you’re actually trying to achieve a kind of innovation through limitation most of the time, and a natural style has evolved. Since you don’t have those impediments in CG, animators actually have to use a lot of restraint to preserve it.”

Melding the two animation styles was a trial-and-error exercise in the character rigging stage of production. During this phase, fully modeled and rigged characters are created in the computer based on the art department’s designs and specifications, as well as the needs of the animation team.

Some of the benefits of working in CG were immediately apparent. “Consider The Toad,” offers Newitt. “You have a massive bell-shaped body with very spindly legs. There’s so much weight to support and almost nothing to carry it. A character like that is an absolute nightmare to produce in stop-motion, but in CG, you don’t have to worry about gravity.”

Of course, there were also challenges during this translation process. “When we started doing the rigs, they matched the Aardman puppets almost exactly,” says lead character technical director Martin Costello. “But we found that some of the movements really didn’t work well in computer animation. So they evolved into something new, though there are still many similarities with traditional Aardman puppets, particularly the mouths and the brows.”

In traditional stop-motion, animators use a variety of mouth pieces for each character. These pieces are removed and replaced with different shapes in nearly every frame which allow the animators to not only make their characters speak but also create different expressions. To recreate this look in CG, the rigging department generated those replacement shapes within the computer. “In stop-motion, they physically remove one mouth shape and put in another in nearly every frame,” Costello notes. “So we made sure we could do the same thing on the computer.”

One of the most difficult components of the CG facial rig was the trademark Aardman monobrow. On a clay figure, the monobrow is a piece of plasticine that hangs above the eyes, small plastic spheres which are pushed into the brows to form sockets.The brow is then raised slightly to form two furrows above the eyeballs. Costello cites Gromit – the silent canine partner of Aardman’s Wallace and Gromit franchise – as the best example of the brow’s importance. “Gromit doesn’t speak; he basically does all his acting with his brow. It’s very subtle and it’s a real mark of Aardman animation. So we had to mimic that in ‘Flushed Away.’”

It took months to develop a CG rig that captured the right level of expressiveness. The monobrow rig had to reflect the clay-like feel of the character’s brow. Controls were added to the eye sockets to form a ridge, a sort of “false-brow” upon which the protruding brow would rest. Other controls were added to flatten and fatten the brow. Frown lines were added as scalable displacement maps to imitate the scoring of clay by modelling tools.

“Aardman animators move the characters’ faces by hand,” Costello says. “Their fingers can make the smallest changes to reflect a character’s emotions or thoughts. The computer controls had to give our animators that same ability, because obviously we can’t just give the computer a giant thumb.”

Thumb or no thumb, the Aardman thumbprints are all over the characters of Flushed Away – literally and figuratively. When Spike receives an electric shock, the skeleton that shows through is actually a stop-frame armature. And if you look closely enough, Bowers shares,“you’ll see in some rare spots, some of the characters even have a few thumbprints on them.”

Team Players

No man – or mouse – is an island. Behind each of the memorable personalities gracing the screen in “Flushed Away,” there was a team of talented artists, animators, and actors working together to bring that character to life.

“‘Flushed Away’ has some great comic characters,” Lord continues. “I think the villains in particular tend to steal the show a bit. We’ve taken great pains to try and get real performances and a story that people really care about. And it is a strong, exciting story, with lots of very big laughs.”

“Our hero, Roddy St. James, is a privileged society mouse living a spoiled but solitary life in Kensington, an upscale London neighborhood,” Bowers reveals.

“He thinks he has a wonderful life that involves a lot of play and very little responsibility. But he doesn’t have any family or real friends, so he has to make do with the toys and bits and pieces around the apartment.”

“He doesn’t really know much about the world,” Fell adds. “He lives in this bubble – albeit, a very beautiful and luxurious bubble – but he’s quite naïve.”

When he takes an unanticipated tumble into London’s sewer city, Roddy is faced with a world completely different from his own. It is immediately clear that this inadvertent adventure will be an eye-opening one.

Hugh Jackman, who gives voice to Roddy, explains his character’s shock at his sudden change in circumstance. “When Roddy is flushed down the loo, it’s not just like being a fish out of water – it’s like being on Mars. He has never been outside his house before; he’s always well-dressed, always clean, and always alone. All of a sudden, he’s not only in a new world, he has to fend for himself among hordes of strangers.”

“Hugh made Roddy even more charming than we thought he could be,” Bowers says. “Hugh is obviously a very talented dramatic actor, but he’s also got a lovely light comedy touch. Roddy became much more fun, really a nicer guy, when Hugh got involved. And he could sing! We didn’t expect that, but once we heard him, we knew we had to find a way for Roddy to sing in the movie.”

Jackman, who won the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical in 2004 for his portrayal of singer-songwriter Peter Allen in “The Boy from Oz,” admits, “I’ve done a little bit of singing. When we first started working, Sam and David said, ‘We have an idea for a scene where Rita kicks you off out of the boat. You’re on a raft made from a rubber duck, and she throws you a guitar to use as a paddle. But instead, you use it to charm her by singing a song.’ We made it up on the spot.”

Rita – played by Kate Winslet – is everything that Roddy isn’t. She’s an independent, street-smart skipper who lives in the moment and takes risks, but is also determined to support her enormous family. Roddy and Rita find themselves thrown together for the adventure of a lifetime.

“Roddy’s given a tip that Rita is the only one brave enough to take him on the dangerous journey back to his home,” Winslet explains. “And the two of them develop an unlikely friendship that sort of turns into an even more unlikely romance. It’s certainly a case of opposites attracting.”

Fell adds,“Rita and her dad make a living as scrap dealers on this boat called the Jammy Dodger. She’s a bit wild, a little bit chaotic, a little vulgar – she’s got some rough edges. But she’s also brave and adventurous. So she might get into some trouble, but she always manages to get herself out of it.”

“We thought of her as a sort of ‘Indiana Joanna,’” says Kramer. “Rita is really the quintessential street girl,” says Simon Otto, the supervising animator who developed Rita’s look. “At first,we created a character that was attractive, but extremely tomboyish. Red-haired, scrappy, a bit disheveled. Kate added a feminine nuance in her voice work, and I think Rita really ends up as something of a cross between a beautiful siren and a construction worker.”

Winslet identifies with her character. “I think I am something like Rita – every girl should be. Tough, exciting, and interesting. I try to be as strong as I can be. I think that’s a very important quality for us girls to have.”

If Rita is unrefined, Sid – Roddy and Rita’s unknowing matchmaker – is downright uncouth. After a burst sewer main rockets him up the pristine kitchen sink, Sid, a crass but jovial sewer rat, sets up residence in Roddy’s Kensington flat. Rather than be evicted from his plush new surroundings, Sid flushes away his displaced host. Adorned in a T-shirt made from underpants and trousers that can’t contain his sizeable belly, Sid punctuates his first scene in the movie with the longest belch in the history of animation.

“Sid is filthy and unrestrained, and though he’s really not an evil guy at all, he’s a threat to Roddy’s way of life,” Fell states. “Sid has led a fairly tough life in the sewer, and has no desire to leave this luxurious place. He’s a dirty, energetic character who has invaded Roddy’s clean little bubble. Sid is chaos, and Roddy doesn’t like chaos.”

British star Shane Richie provided Sid’s voice – and more. “Sid’s flamboyant and a bit odd, so Sam and David let me ad lib quite a bit,” Richie says. “So people who know me will likely say,‘Oh well, Shane’s added that bit.’ I certainly threw a bit of my personality in there.”

Lionel Gallat, the supervising animator responsible for bringing Sid to life, noted that Sid’s girth was a challenge for the crew. “Sid is fat,” Gallat asserts. “It’s difficult for our riggers to give a portly character good definition. And sometimes their size restricts movement, which means that they have to create a lot of controls to shape different kinds of physical actions. Sid’s belly could have gotten in the way when he’s looking down into the toilet bowl, for example. But the riggers did such a good job with him.”

While Sid happily adjusts to his lavish accommodations, trouble is brewing for the rodents down below; the comically sinister Toad is plotting their widespread demise. “The Toad is a big, bombastic, overbearing, huge, green monster,” says Bowers. “He used to be Prince Charles’ pet, but he was replaced by a mouse and flushed down the royal toilet into the London sewers. So he harbors a deep-seated resentment towards all rodents, and it’s his plan to wipe them all out.”

The Toad is voiced by Ian McKellen. Bowers adds,“We asked him to bring all of his Shakespearean pomp to the role, because The Toad sees himself as sort of a sophisticated, suave, Noel Coward-type… even though everyone else sees him as Jabba the Hut.”

“I never think of the characters I play as unpleasant, even if they’re Richard III,” says McKellen, sympathetically. “Toad’s had a hard life. He got flushed down the loo when Prince Charles handed over his favors to a new pet. Of course, Toad was disappointed, to put it mildly, but down below, he came into his own. He’s sentimental about his past, but he was turned by fate and he has a very strong nasty side as well.”

“Toad is very baroque and broad in his gestures, and very fun to work with,” says supervising animator Jason Spencer-Galsworthy, who led the team that animated The Toad. “He’s the villain of the film, and the villain is often the character that has the most interesting nuances. There’s a perception that if you’re big, you’re also slow and lumbering, and we didn’t want Toad to be like that. To get an idea of how he should move, we looked at videos of larger icons – Noel Coward, Alfred Hitchcock, to name two – who are also quick and powerful, who have incredible energy. You feel like he can be a real physical threat at any moment, even though he usually relies on his henchrats to do his dirty work.”

Spike and Whitey are the Toad’s chief henchrats, tasked with retrieving the Toad’s secret weapon from Roddy and Rita. Much to their ruthless employer’s chagrin, this twosome is low on talent, brains, and killer instinct. They are, according to Fell,“really just a couple of idiots. They really want to be bad guys, but they’re just not any good at being bad.”

Andy Serkis, who voices Spike, adds, “Spike and Whitey are a double act. Spike is lethal, absolutely lethal… in his own mind. He’s actually soft as anything, and kind of a nervous, twitchy rat who still lives with his mum. And he compensates by bossing around Whitey, who is three times his size.”

“Whitey is an albino ex-laboratory rat,” explains Bill Nighy, who provides Whitey’s voice. “He was involved in some quite sophisticated shampoo experiments involving overexposure to hallucinogenics, which may well have contributed to his lacking intellect. He’s a big lumping character who is really a perfectly nice chap with a difficult job.”

Producer Cecil Kramer adds, “I have a soft spot in my heart for Whitey. He’s rough and tough on the outside, but on the inside, he’s a complete mush.” Serkis found the process rewarding. “You inhabit the character and you play the situation,” he says. “I was fortunate in that the first section I did, Bill and I got to work together. That was such a relief, because if you’re doing a double act, you have to be able to play off the other person.”

Nighy concurs, “The phenomenon of hearing your voice coming from this animated creature is thrilling.”

When it becomes obvious that neither Spike nor Whitey can keep up with Rita and Roddy, The Toad calls up his ruthless and rubbery French cousin, Le Frog. A rather snooty mercenary, Le Frog is more passionate about having time for a leisurely dinner than he is about his cousin’s maniacal plan. French actor Jean Reno provides the voice of Le Frog.

“He is the archetype of a bad guy more than a French archetype,” Reno describes. “He’s got some stereotypical French traits – his relationship with food, with girls – but there’s also the very smooth villain. He’s colorful, and I like that.”

Bowers admires Reno’s sense of humor as much as his talent. “Jean was a real trooper,” he chuckles. “You know, the Brits and the French have poked fun at each other over the last, oh, five million years. We make fun of the Brits too, of course, but even so, there were certainly a few little gags that we sort of worried about handing over to such a respected French actor. But Jean didn’t mind in the least.”

Le Frog’s distinct form dictated his range of motion. “He’s shaped a bit like an M&M, which can be tricky to animate,” says Mark A. Williams, the supervising animator who oversaw many of the key Le Frog scenes. “You can’t really rotate the spine and neck joints. So basically, you rotate him from the hips and give him very stretchy arms and legs. The way he moves actually adds to his humor.”

Cecil Kramer reflects on the ensemble. “We never had all of our actors in the room at the same time,” she offers. “In fact, we recorded across ten cities, six countries, and three continents. But because we had just the right combination of talent – the right people in the right roles – the characters came together perfectly.”

From “Up Top” To Bottom

To emphasize the contrast between Roddy’s life of lonely luxury and the vibrant chaos he discovers when he’s flushed from it, the filmmakers were determined to design two dramatically different worlds. Their efforts resulted in the wild subterranean setting of Roddy’s tremendous adventure – the polar opposite of his polished, impersonal “Up Top” flat.

Everything is in perfect order in Roddy’s extravagant home, and when his owners are away on holiday, Roddy has the run of the place. Fell explains, “Roddy is the pet mouse of a rather wealthy family living in Kensington. He lives in this gorgeous, gilded cage, is dressed in the finest doll clothes available, goes skiing on little mountains of ice cream. He plays volleyball with his toy pals and drives them around in his toy sports car. And he’s really quite happy there – or rather, just assumes he is because he doesn’t know anything different.”

Since the film is set in and underneath London, one of the first steps in the production design process was a trip to the Square Mile itself. “We took so many photos,” remarks co-art director Pierre-Olivier Vincent. “We captured every little detail – the windows, the doors, the stairs, the signage – because things like these are very unique to a city.We really tried to absorb the mood of the city.”

While the idea of the city often evokes images of rain and gloom,Vincent noted that London was practically awash in bright hues. “We think of London as a very dark city because the weather is often overcast, but it’s actually very colorful. There are a lot of reds, a lot of whites. Most of the windows have that white framing. The doors are often bright blue or green or red. Even the bricks are a very distinct color.”

In the film, matte paintings provide the backdrop for above-ground London. “We started out with the photographs of the real place,” says Ronn Brown, matte painting supervisor. “Once we have those photographs, it’s kind of like making a collage. When we’re painting, we’re essentially putting all those photographs together, adding in the light, the values, and the shape.The goal is to be realistic within the style of the film – sort of ‘realistic with a twist,’ always adhering to that Aardman style. With Big Ben, for example,we’ve kind of exaggerated the shape of the building to give it more of that sculptural Aardman look.”

Underneath Kensington, the vibe and pace are quite different. It’s a bustling, unruly place, and for a pampered pet accustomed to order and predictability, it is simultaneously terrifying and exciting. Roddy’s home is clean, comfortable, and safe – but it is also somewhat cold and uninspiring. The underground world, conversely, needed to be almost magical.

“There had to be a little bit of coldness in Roddy’s world because we needed him to eventually become attached to the world down below,” explains co-art director Scott Wills. “So he goes from a world that is really white and pristine into something darker and more complex. But it’s a balancing act – Roddy has to find the world overwhelming and intimidating at first, but it can’t be too scary and off-putting either, because he has to fall in love with it.”

To draw inspiration for this world, the filmmakers visited an area of London that can hardly be considered a typical tourist attraction. “We took a field trip down into London’s sewers,” Bowers shares. “We got all kitted out in Hazmat suits and protective masks and had to climb down a 50-foot ladder.”

The excursion revealed a less-than-picturesque environment. “There was nothing down there,” Bowers laughs. “We were expecting to be very inspired by what we saw, and while it really was impressively expansive, it was quite empty. We asked one of the men who worked down there where the rats were. He said, ‘Oh, it’s too deep for rats. No rats down here.’ So that was a bit of a surprise.”

But the trip did reveal surprisingly beautiful Victorian architecture and brickwork, which production designer David A.S. James was sure to capture on camera. “I took a lot of digital stills down there,” he recalls,“even though there was a guy behind us warning us not to use too much flash because it could possibly trigger a methane explosion. Not exactly your typical workday in CG animation.”

Once they were back in a less incendiary environment, the team began designing an alternate vision of London itself for the sewer world. While the mood and pace differ considerably from “Up Top,” the city’s influences are obvious in this underground metropolis; the designers reconstructed London’s notable landmarks with discarded items from the world above. In the alternate Piccadilly Circus, an old jukebox serves as a record store and a discarded arcade machine functions as an arcade. The subterranean Big Ben is comprised of a washing machine, a picture frame, a wall clock, and cups. The London taxi is a converted boot, and the newsstand is a repurposed motorcycle helmet.

Visual effects supervisor Wendy Rogers notes that to build the complicated and visually stunning world beneath the streets of London, the artists referenced an early were assisted physical set built by the team at Aardman and attempted to replicate that look in the computer. “It really was a design challenge, and I think that’s where Aardman really lent a hand. They gave one of their set builders a pile of garbage and said, ‘Go build an underworld.’ It’s really fun – every time you look at the movie, you’re going to find something different in the set.”

The Jammy Dodger – Rita’s boat – is one of the team’s most inventive creations. “The boat has quite a bit of screen time,” James continues. “So we knew it had to be very interesting to look at. There are tennis balls for the bumpers. The back of the boat is a tire. The cabin is made from a gas can. The helm is a water tap, the throttle is from an old slot car racing set, the secret devices are triggered by typewriter keys… the list just keeps going.”

Rogers notes that had the film been a traditional Aardman stop-motion film, the Jammy Dodger and the world it inhabits would have approached life size. “If our Roddy and Rita puppets were ten inches tall, the he entire underground city would have been 140 feet across to be proportionate and the Jammy Dodger would have to be five feet long,” she says. “With so many scenes taking place on that boat, with all its moving parts – the swinging Vegas dice, the mirrors – it was just too big a job.”

Thousands of 3D models were needed to create Kensington and the dizzying world below. Modeling is the creation of all of the characters, props, and environments in geometric form. “It’s kind of like digital sculpting,” modeling supervisor Matt Paulson explains. “It’s taking the concepts and images and actually recreating them on the computer.”

“Flushed Away” was incredibly challenging from a modeling perspective. Paulson says, “Typically, DreamWorks Animation films require anywhere from 1500 to 1700 individual models. Flushed Away had well over 3000. There’s a lot of complexity, a lot of unique models that we put together to create a sophisticated, elegant world Up Top, and the sewer, where everything’s scattered and trashed a bit. Making those two worlds separate but equally appealing was one of our biggest challenges.”

Rollin’ On A River

Since CG animated movies are constructed within a virtual environment, it’s easy to underestimate the importance of one of the most fundamental pieces of filmmaking equipment – the camera. Cinematography is just as critical in CG as it is in live action or stop-motion.

On physical movie sets, camera work is restricted by space and gravity. To film a scene from above, cameras typically run on tracks. Depending on the complexity of the shot desired, these structures can require intricate scaffolding and considerable manpower. And even with this effort, there will still be some limitations to the camera’s range of motion.

Of course, gravity doesn’t exist in CG. A scene can be filmed from any angle in any motion the cinematographer desires, and an aerial shot is as straightforward as one on the ground. “We were able to fly the camera around,” Kramer says, “and that paid off beautifully in the boat chase, which is one of the most important sequences in the movie.”

In “Flushed Away,” this freedom of movement is needed to be restrained in order to preserve the Aardman style. Co-head of layout Frank Passingham notes, “In terms of the camera movement, we wanted to keep the perspective very grounded, for the most part. I think we’ve emulated the Aardman look in the camera and lighting work as well as the animation.”

Co-head of layout Brad Blackbourn was mindful of this objective in overseeing the transition between storyboards and full animation. Layout involves blocking a rough version of the characters through their intended movements on the computer. In addition to character movement, layout artists must also recreate the camera perspectives implied in the storyboards.

During this stage, the preliminary camera movement, lenses, and angles are selected. It’s at this point, Blackbourn comments, that the crew is really “getting a feel for the geography of the set.”

“Everything breaks down into frames,” Passingham adds.“You need to think about not just the camera move that you’re working on, but the camera move that you just cut from, or are about to cut to. There are always accelerations and decelerations in movies, and you’ve got to be very careful about those. Those decisions dictate the speed of the camera you use, and the width of the lens.”

Blackbourn recalls the early stages of camera work on the scene that introduces the audience to The Toad’s ice room. “We wanted to try to play up the power of this scene,” he explains.“Roddy and Rita come face to face with all of the rats Toad has frozen. We wanted to give it sort of a ‘death chamber’ feel, when it’s basically a refrigerator. We used around 100 shots for this sequence, to cover every possible angle. And we used some really wide angle lenses and low perspective.”

The majority of scenes in “Flushed Away” were filmed with 35-, 24-, and 18-millimeter lenses. “The characters’ noses required us to be especially careful with the lenses,” Passingham explains. “Roddy, Rita, Sid – they’re rodents with long noses. When you’re using a wide-angle lens, those noses can almost project right off the screen, so you have to stay on top of that.”

Camera movement was just as tricky as lens selection. For the sequence where Roddy is flushed from his home, the camera’s motion was carefully designed to capture his disorientation. “We wanted Roddy to be spiraling, descending quickly, and very shaken,” Passingham says. ‘So while we’re tracking forward, we’re actually sort of spiraling in the camera at the same time. And putting a bit of shake in the shot, some rough camera movement to show that he’s really being buffeted as he’s propelled along the popes. The camera motion really conveys that he’s taking a rather tough and extensive trip to the sewer world.”

The climactic boat chase on the Jammy Dodger was one of the most challenging sequences to shoot. Bowers summarizes the scene: “Roddy and Rita are being chased by Spike,Whitey, and the rest of The Toad’s bunch. Rita hits the turbo boost, the fire extinguisher goes off, and the Jammy Dodger just shoots down the tunnel.”

“The first thing we had to work out was the speed of the boat,” Passingham recalls. “At the beginning, the boat only uses one steady speed, then there’s a different speed when the chase begins, and then a final speed once Rita switches on the booster. And those speeds actually dictated the length of the tunnel.”

The backgrounds were blurred to convey a sense of motion and speed. But to really make the sequence spectacular, the team turned to perhaps the most celebrated chase scene in motion picture history.

“We realized that our chase was actually similar to a car chase, so we actually used the car chase sequence in ‘The French Connection’ as a reference. In that film, a lot of the cameras were actually mounted on the bumper of the cars. So we used a similar approach, and mounted a camera close to the water. It really captures that sense of speed and makes the shot look even more thrilling.”

The Wet Look

While water is considerably more problematic in stop-motion, it’s not exactly easy in CG. Lighting artistic supervisor Mark Edwards notes,“Water is particularly difficult because, obviously, people already know what it looks like. They know how it moves and behaves, and they’re going to be watching with a critical eye. So we needed to capture just enough realism in the water’s appearance and movement without disrupting the movie’s visual style.”

To design the varying water patterns, the effects team combined technology with basics: fluid-simulating software inspired by the real physical properties of water.These physical experiments are used as references, and then it’s up to the effects team to translate the real-life visuals into CG.

“There’s a scene right after Roddy is jettisoned out of a pipe and up against a sewer grate and is doused with water,” Lindquist recalls. “We weren’t sure exactly how that should look, how the water would appear on impact, how it would drip off Roddy’s body. So we got some buckets, some hoses, some volunteers, and went outside.”

The reference for the toilet flush scene was a little more challenging to obtain. “Toilets that aren’t low-flow are practically nonexistent in Los Angeles,” Kramer explains. “We went outside the country to find the right flush. The whirlpool that sucks Roddy underground was actually inspired by footage of a toilet in a British pub, courtesy of one of our Bristol colleagues.”

Lindquist adds, “The flush scene is actually a sequence of three shots, using two different techniques to achieve the look. The first two shots were created by taking a flat surface and deforming it into a shape that closely resembled the flushing water from the pub footage, and the third is where the water actually goes down. This is all done with the fluid simulator. We input the speed of the water, and the desired movement, and we just let the simulator run. At that point, it’s just tweaking and fine tuning.”

Lighting the flush sequence presented its own unique challenges. Similar to illuminating sets in live-action films or theater stages, CG lighting is essential to shaping the forms on the screen and in establishing depth of field – attracting the audience’s focus to the desired character or action so that they are not distracted by all of the tertiary details within the frame.

Edwards offers, “I don’t think anyone has ever attempted an actual flushing toilet with swirling water, so we weren’t working off of any precedents. It was challenging, trying to get the proper caustics and balance the reflections, but I really like the way the scene turned out. It’s really wild, and certainly one of the key moments in the film.”

Slugging Out The Score

When it comes to setting the mood of a film, there’s no substitute for a well-conceived score and some well-chosen songs. From the fast-paced chase sequences to the tender moments in Roddy and Rita’s budding relationship to the slugs’ frequent comedic appearances, music provides an indispensable aural backdrop for “Flushed Away.”

“We wanted a classic score, one that would really strike the balance between comedy and adventure, which is really what this film is,” explains Fell. “In some ways, it’s like an ‘Indiana Jones’-type movie, with fabulous action sequences, but in other places, it’s really quite silly and comic. We were looking for something that recalled the old cartoon scores like Carl Stalling’s arrangements with Tex Avery.”

To bring this score to fruition, the directors turned to Harry Gregson-Williams. “We were very lucky to have Harry,” Bowers states. “He did the ‘Shrek’ films, and ‘Narnia,’ and he’s produced this sort of sweeping London-esque, fantastically uplifting score that we just love.”

Having composed the score for several DreamWorks Animation films, Gregson-Williams embraced the process of composing for “Flushed Away.” He states, “It’s a particularly collaborative experience, scoring an animated movie. It’s quite a substantial commitment, compared with live action. It’s never really finished until it’s finished. Cues change, scenes expand. I’ll start developing the music when the film is in the storyboard stage, then adjust it as I go along.”

When he first started composing the “Flushed Away” score, Gregson-Williams focused at first not on the beginning of the film or any of the fast-paced action sequences, but a poignant moment in the middle of the movie. “There’s a scene in the middle of the film where Roddy and Rita are having dinner, and she’s asking him to tell her about himself,” he says.

“And Roddy claims to have a wonderful life, surrounded by friends and relatives. But it’s not true, and he’s beginning to realize that he’s actually sad about that. It’s a subtly emotional scene, and a momentary break from the frenzied pace of the film. It might sound a bit odd that I would start in the middle, but I saw it as the point where it all ties together. Having started there, I then doubled back to the beginning of the movie and thematically built towards that crucial scene.”

The song selection was equally deliberate, and ultimately parallels the somewhat haphazard quality of the sewer world. “We have a fairly eclectic selection of songs and artists,” Bowers notes. “We wanted it to be fun, but we also wanted to capture a wide variety of different feelings, because it’s a city, complete with that urban city feel. So we have several artists, including the Jets, the Dandy Warhols, even Tina Turner.”

But the filmmakers didn’t limit themselves to established musicians;“Flushed Away” also marks the musical debut of the scene-stealing slugs. These slippery singers started off as extras, just another kind of unfamiliar creature for Roddy to encounter with trepidation. But Fell and Bowers soon realized that the slugs had some serious comic potential.

“We started off with just a few slugs that let out these hilarious high-pitched screams when Roddy first meets them,” Fell recalls. “But they were so funny and cute, we started to look for other spots in the film for them to show up.”

Since the slugs had become a crew favorite, the bid to increase their screen time was well-received. “Before long,” notes Kramer, “we were thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to have them singing?’ So they became something of a comic Greek chorus, which contributed to the kind of silly, whimsical, humorous style of our movie.”

While the slugs do provide the background vocals for a scene where Roddy serenades Rita from the underground river, Bowers admits that there was some lip-synching involved in the finale, a spirited rendition of “Proud Mary.” “We really wanted to hear Tina Turner’s voice coming out of those slugs. We just thought it would be very funny. And it is.”

These production notes provided by DreamWorks Pictures.

Flushed Away

Starring: Hugh Jackman, Kate Winslet, Ian McKellen, Andy Serkis, Bill Nighy, Shane Richie, Geoffrey Palmer, Jean Reno

Directed: Sam Fell, David Bowers

Screenplay by: Dick Clement

Release Date: November 3, 2006

Running Time: 86 minutes

MPAA Rating: PG for crude humor and some language.

Studio: DreamWorks Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $64,665,672 (36.5%)

Foreign: $112,482,829 (63.5%)

Total: $177,148,501 (Worldwide)