Filmmaker Sarah Polley approaches storytelling from a completely different point of view with her documentary “Stories We Tell,” in which she narrates a plot in which she also takes place through the narratives of other witnesses. Saying that he shot this documentary because the same story is told with different emphasis and details, Polley notes that his goal is to create a narrative with confusing details and to make the audience experience what he feels like.

What means memory, or the alteration of memories over the years or their articulation with other memories? And which one of the witnesses of a memory is obliged to tell others about it? Who is more competent for storytelling, or how much a reflection of a past truth shaped by nostalgia?

Directed by Canadian Sarah Polley, “Stories We Tell” does not give a direct answer to these questions about storytelling, which is carried on with first body language, then painting, then language and then its derivatives, but it does not reflect on the essential elements of a story. leads us to examine the above questions.

The filmmaker does this through a documentary that he uses half-and-half real-life footage, based on his personal story. At the center of Polley’s story is her mother, Diana Polley, who died in 1990.

The documentary begins without defrauding the story; Polley gets to know the storytellers, respectively: his father, his siblings, his mother’s friends and friends. Each is part of this story, but we learn this and their role in the story over time, step by step, when their turn comes.

In this sense, Polley takes storytelling to another meaning. While the plot spanning years is told in the language of each witness, the participant, the storytellers re-experience the past with us, which they dragged with them.

In addition to the narratives, the videos that Polley adds ascribing to the past, half from the archive, show us the whirling thoughts of Polley, who is mostly silent among all these storytellers.

In each later phase of the documentary, Polley takes a masterful use of his role between the narrator and the audience, in a way that pushes the left-back part of the story into another context, making the rest look a different perspective.

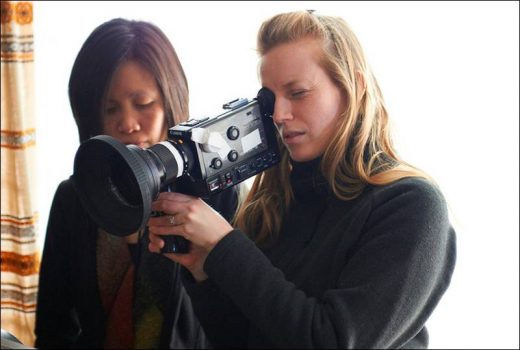

In the interview below, director Sarah Polley talks about how she set up a storytelling, in what context she set up the narrative, and the experience she aims to make the audience live.

When you set out to make this documentary, what value did you see in the project in terms of revealing this narrative?

For me, the story itself wasn’t enough to make a movie about it. I remember these events that happened in my life were really influential for people and me in my life, but I feel like I have seen it many times as a story or a movie. I think the exciting thing about exploring for me and maybe making movies about it was that we were all telling stories about it.

We were all writing or talking about it, and the story changed every time it was told. The third or fourth hand from friends of friends were completely other stories, including mistakes, but sometimes it was the same story; There were completely different emphasis in the various chapters, depending only on what resonated with people. This is what fascinated me; Questions such as why we are telling stories, why do we want to create a story from the complex events in our lives and what kind of basic human need this is…

In “Stories We Told,” you highlight everyone’s quotes about this family affair without including your own point of view – at least until the end of the movie, until you explain your own contribution. If this story happened to one of your siblings and he wanted to make a movie, would you do it again, or is it a combination of your story and perspective?

I think the story itself doesn’t provide enough motivation to turn it into a movie – I thought it wasn’t enough. It’s a good story for the people involved, but I didn’t think it would be a good movie. The motive here was the storytelling around it: the fact that after it happened, we were all telling stories to our friends and to each other within a year of the incident.

Some of us were trying to do creative things about it – write, like my father and Harry, for example – and it was very interesting for me to see how these stories began to diverge and listen to the third or fourth-hand version of the story. Someone comes to you at a party and says, “Hey, I heard this story about you.”

Then he tells you a story that has little resemblance to what really happened to me, or emphasizes different details. I was intrigued by the human impulse to construct a narrative out of an overwhelmingly confusing array of details, and how it goes – like our need to create a narrative when we want to make sense out of life.

How did you approach the storytelling here, what did you use as archive footage and how did you decide to place the interviews like this?

I think my main idea is; Some of them contradicted each other, put the previously revealed detail into a completely different context, and gave different meanings to the audience, as I heard and revealed these details.

I never felt that I was able to put on a solid foundation when I was asking and investigating the story in my life, and I never knew whether what I heard was truth or a longing for the past. What was my experience? So during the making of the movie, I was looking for as many ways as possible to provide the audience with an experience similar to mine. I wanted questions about what he saw. And I felt that if what they saw was linear and direct, I wanted to provide them with a piece of information that would make them question almost everything they had ever seen.

Visits: 133