The apologizing-and-forgiving process mends the broken relationship.

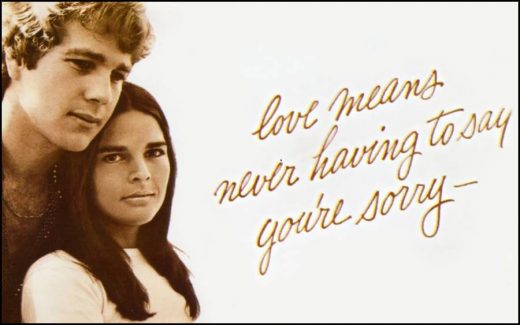

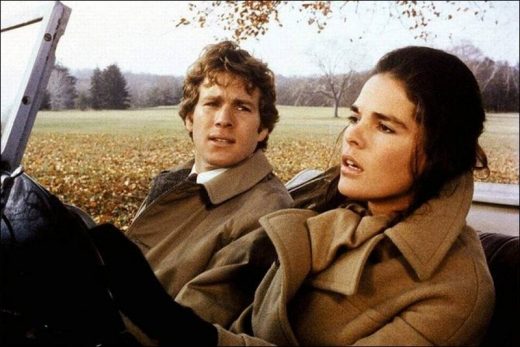

The 1970 movie Love Story, based on the novel of the same name by Erich Segal, tells the story of star-crossed lovers Jennifer and Oliver, who marry against their parents’ wishes. This movie is the source of one of the most famous aphorisms ever to come out of Hollywood: “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

The line occurs twice in the movie. Jennifer says it the first time, when Oliver tries to apologize to her for losing his temper. Oliver repeats the line at the end of the movie, when his father attempts to repent for having disowned his son. Spoiler alert: Jennifer has just died, you see, and the line is a real tear-jerker.

“Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” I just never got it. I was always told you should apologize when you hurt another person. I was also taught to forgive the other person—if the apology was heartfelt and contrite. So why is it you don’t have to apologize when you hurt the ones you love?

I sought the wisdom of the internet, and this is what I found. Barbara Rose, Ph.D., on the website SelfGrowth.com, explains in a post appropriately titled: “Love Means Never Having to Say You’re Sorry”:

True love is unconditional. It is transparent, where we can accept, understand, and allow the other person to make every mistake, falter, stumble, and give genuine heartfelt compassion when they are trying their best, even if their best is can be “better.”

Since there’s no love between us, I guess I can say: “I’m sorry, Dr. Rose, but I just don’t agree with you.”

Is it really true that we should love others unconditionally? I think in some cases we absolutely must, but in most cases, we should not.

Parents do need to love their children unconditionally. Decades of research—as well as common sense—tell us that children who do not receive unconditional love from their parents cannot grow into well-adjusted adults. I also think that children love their parents unconditionally, at least when they are young and dependent.

As adults, children of neglectful or abusive parents will struggle for years with low self-esteem, guilt, and depression. With the help of counselors or loving others in their lives, they may find a way to love and accept their parents. But it certainly won’t be unconditional.

I also contend that friends and lovers do not love each other unconditionally. Nor should they get stuck in the mindset that unconditional love is the norm for these kinds of relationships. We enter into relationships with a spirit of trust and mutual benefit. We also let go of those who repeatedly take advantage of us. Maintaining such a relationship in the name of unconditional love merely sets us up for abuse.

This doesn’t mean that the first transgression spells the end of the relationship. We’re all imperfect people, and we inevitably hurt the ones we love. Whenever there’s been an infringement in the relationship, both the victim and the perpetrator bear considerable psychological burdens until the atonement-redemption cycle is complete. In other words, the apologizing-and-forgiving process is the cement that mends the broken relationship.

In a recent article in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science, Israeli psychologists Nurit Shnabel and Arie Nadler outline their needs-based model of reconciliation to explain why broken relationships can’t move forward until atonement has been made by the perpetrator and absolution has been granted by the victim.

According to Shnabel and Nadler, both the victim and the perpetrator feel psychologically threatened when a transgression has occurred. On the one hand, victims feel that their agency, or sense of ability to choose their own actions, has been compromised. On the other hand, perpetrators perceive a threat to their moral identity.

Knowing that someone has been hurt by their actions causes perpetrators to feel guilt or shame. Even when they rationalize their actions, an awareness that others view them as morally wrong induces anxiety. For example, you may have felt justified in losing your temper with an incompetent coworker, but now knowing that the rest of the office judges you negatively puts you in an awkward situation.

Shnabel and Nadler call their theory the “needs-based model” because both sides in a transgression have psychological needs that must be met before the rift in the relationship can be mended. Victims need their sense of agency restored, and perpetrators want to recoup their moral identity.

A sincere apology and act of atonement returns a sense of agency to the victim, who can now decide whether or when to forgive. Thus, the victim’s psychological need is met. Likewise, the act of forgiving restores the moral identity of the perpetrator, who has atoned for the transgression and been redeemed.

The needs-based model is supported by a series of experiments in which pairs of participants are engaged in a competitive task. Afterwards, some are led to believe they have been deceived by their partner, while others are led to believe that they had deceived their partner. In questionnaires, both “victims” and “perpetrators” reported the kinds of psychological states predicted by the model. (The researchers don’t report whether they apologized afterward for the deception.)

Society fills our heads with all sorts of nonsensical notions about how we should think, feel, and act. The idea that love means never having to say you’re sorry is emotionally appealing. Yet nothing could be further from the truth.

Especially when we’ve hurt someone we love, we absolutely need to apologize—sincerely and contritely. It’s the only way to start the healing process in a broken relationship. In other words, love means having to say “I’m sorry”—and “I forgive you.”

Visits: 531