The moments we remember from the first years of our lives are often our most treasured because we have carried them longest. The chances are, they are also completely made up.

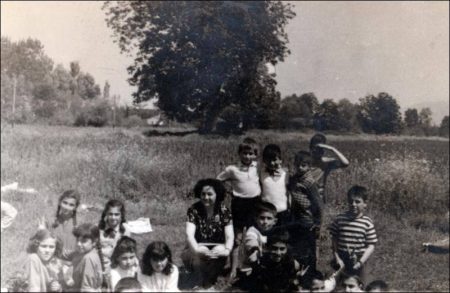

I’m prancing around at a party in a garden with incredibly neat flowerbeds on a scorching summer’s day, enjoying the attention of my grandmother and of the older children who are wearing puffy pastel dresses. I was around two years old at the time. My recollection of this is fuzzy and indistinct, but nonetheless, it feels authentic and I treasure it as one of my earliest memories.

There’s just one problem: I’m not certain it’s real. According to my parents, I may have made up many of the details from a photograph of a party at a neighbour’s house in the 1980s.

Around four out of every 10 of us have fabricated our first memory, according to researchers. This is thought to be because our brains do not develop the ability to store autobiographical memories at least until we reach two years old.

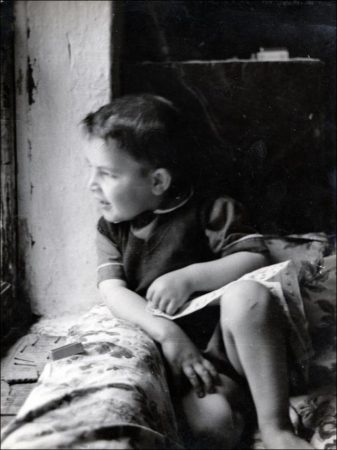

“While infants can make memories, they are not long-lasting,” says Catherine Loveday, an expert in autobiographical memory at the University of Westminster. The flurry of new cells forming in the brains of young children are thought to disrupt the connections needed to store information long-term. It’s why most of us have few memories of our childhood by the time we are adults. Other studies have shown that a form of “childhood amnesia” seems to kick in once we reach the age of seven years old. (Read more about why we can’t remember being a baby)

Yet a surprising number of us have some flicker of memory from before that age. A study led by Martin Conway, director of the Centre for Memory and Law at City University of London, examined the first memories of 6,641 people. The scientists found that 2,487 of the memories shared, such as sitting in a pram, were from before the participants had reached the age of two, with 14% of participants claiming to remember an event before their first birthday, and some even before their own birth.

Conway and his team concluded that these memories were unlikely to be of real events because of the age they were captured at. If this is true, it suggests that many of us are carrying around memories from early chapters of our lives which never happened.

The reason may tap into something far deeper in the human condition – we crave a cohesive narrative of our own existence, and will even invent stories to give us a more complete picture.

“People have a life story, particularly as they get older and for some people it needs to stretch back to the very early stage of life,” Conway explains.

The prevailing account of how we come to believe and remember things is based around the concept of source monitoring. “Every time a thought comes to mind we have to make a decision – have we experienced it [an event], imagined it or have we talked about it with other people,” says Kimberley Wade, a psychologist who researches memory and the law at the University of Warwick. Most of the time we make that decision correctly and can identify where these mental experiences come from, but sometimes we get it wrong.

Even those of us who should know better can fall into the trap. Wade admits she has spent a lot of time recalling an event that was actually something her brother experienced rather than herself, but despite this, it is rich in detail and provokes emotion. “All of these things make it feel really plausible like a real memory and something I’ve experienced, whereas it’s something I’ve only talked about a lot,” she says.

It provides a clue as to how these false memories can become lodged in our minds. Other people, even strangers, can re-write our history Memory researchers have shown it is possible to induce fictional autobiographical memories in volunteers, including accounts of getting lost in a shopping mall and even having tea with a member of the Royal Family.

Julia Shaw, a psychological scientist at University College London, has even shown it is possible to convince people that they committed a violent crime that never happened. Using memory retrieval techniques, participants were asked leading questions over three interviews, which led to 70% of them generating a false memory of a crime they commited when they were younger, with some even believing they had assaulted someone with a weapon. Almost three-quarters with these false memories could even provide vivid descriptions of what police officers looked like.

It demonstrates that in a highly suggestive interview, people can quite readily generate disturbingly rich false memories.

“Based on my research, everybody is capable of forming complex false memories, given the right circumstances,” says Shaw.

But exactly how susceptible someone is to these sorts of implanted memories can vary. One recent scientific review suggested that 47% of people involved in such studies tend to have some sort of induced recollection of a fictional memory, but only 15% generate full memories.

In some situations, such as after looking at pictures or a video, children are more susceptible to forming false memories than adults. People with certain personality types are also thought to be more prone.

“If you’re the sort of person who can read a book and become so highly absorbed that you no longer notice what’s going on around you… you may be more prone to memory distortion,” says Wade.

But carrying around false memories from your childhood could be having a far greater impact on you than you may realise too. The events, emotions and experiences we remember from our early years can help to shape who we are as adults, determining our likes, dislikes, fears and even our behaviour.

Food may not seem like an obvious choice for testing the impact of fictional memories, but approximately 20 experiments have shown how implanting false recollections of a tasty or disgusting meal can alter what people choose to eat in the long term. In one study, 180 volunteers were told they had become ill from eating egg salad as a child and although this was untrue, a “significant minority” came to believe they had been sick, and as a result, began to avoid egg sandwiches immediately, and continued to do so even four months after the experiment.

In fact, experts have managed to turn people off all sorts of foods by convincing them it had made them ill when they were a child, including, ambitiously, strawberry ice cream. In a review of such experiments, researchers said rarely eaten foods, even if they are sugary treats like ice cream, “appear to be more amenable to false memories of sickness”, while people are less likely to believe that common snacks like cookies made them sick.

Just as people may be put off drinking if they have spent the morning after a heavy night feeling queasy, false memories can affect people’s attitudes and behaviour towards drinking alcohol. In one experiment, scientists suggested participants had become sick after drinking rum or vodka in the past and many of the participants came to believe the false feedback and refrained from choosing tipples containing these spirits.

While this may seem like a bit of fun, many scientists believe the “false memory diet” could be used to tackle obesity and encourage people to reach for healthier options like asparagus, or even help cut people’s alcohol consumption. Interestingly, scientists have also found positive suggestions, such as “you loved asparagus the first time you ate it” tend to be more effective than negative suggestions like “you got sick drinking vodka”.

However, false autobiographical suggestions can have serious consequences too, especially in court.

Kevin Felstead of the British False Memory Society says the impact of such false memories can be “catastrophic” in the real world.

“Miscarriage of justice, incarceration, loss of reputation, job and status, and family breakdown occur,” says Felstead, who noted that he knew of one high-profile case in which the complainant killed themselves.

One of the major problems with legal cases involving false memories, is that it is currently impossible to distinguish between true and fictional recollections. Efforts have been made to analyse minor false memories in a brain scanner (fMRI) and detect different neurological patterns, but there is nothing as yet to indicate that this technology can be used to detect whether recollections have become distorted.

Perhaps the most extreme case of memory implantation involves a controversial technique called “regression therapy”, where patients confront childhood traumas, supposedly buried in their subconscious. The method is prone to inducing false childhood memories, according to the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and is thought to have sparked the “satanic panic” of the 1980s and 1990s, in which some people were imprisoned for hideous crimes such as burying children alive and ritualistic sexual abuse that are now thought to have been based on false memories. Arguably, one of the most serious cases was a couple of daycare workers who spent 21 years in prison after they were accused of cutting the heart out of a baby, burying children alive and throwing others into a swimming pool full of sharks, before being found innocent in 2017.

And our memories aren’t just suspecetable to suggestion. We are all unreliable narrators of our own stories as we go through life.

“Memories are malleable and tend to change slightly each time we revisit them, in the same way that spoken stories do,” says Loveday. They are influenced by our perceptions, state of mind, knowledge and even the company we are in when recalling events, which can lend us a new perspective on a familiar life event. “A memory is essentially the activation of neural networks in the brain, which are consistently modified and altered,” she says. “Therefore at each recollection, new elements can easily be integrated while existing elements can be altered or lost.”

This is not to say that all evidence that relies on memory should be discarded or regarded as unreliable – they often provide the most compelling testimony in criminal cases. But it has led to rules and guidelines about how witnesses and victims should be questioned to ensure their recollections of an event or perpetrator are not contaminated by investigators or prosecutors.

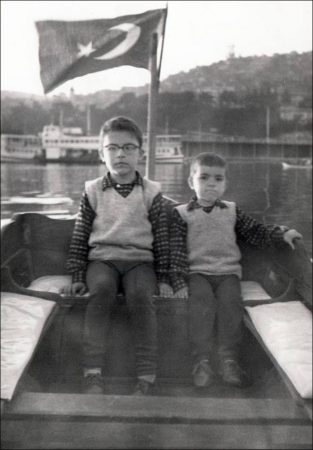

For those of us simply hoping to find out if a cherished childhood memory is true or not, the best solution is to search for proof that it really happened – a photograph, childhood video or diary entry. But not all of our parents documented our every step as a child.

“There is no perfect solution to determining if a memory is real or not because people can have extremely compelling detailed memories that are full of emotions and they feel very confident about but be wildly wrong,” says Wade.

There are, however, some rough rules that can help.

Memories before the age of three are more than likely to be false. Any that appear very fluid and detailed, as if you were playing back a home video and experiencing a chronological account of a memory, could well also be made up. It is more likely that fuzzy fragments, or snapshots of moments are real, as long as they are not from too early in your life.

It’s natural for there to be gaps and things you can’t remember, says Wade. “We shouldn’t expect memories to be clear and coherent like a film.”

Martin Conway also suggests trying to spot implausible details. One of his earliest memories involves him sitting in a nappy digging dirt out of pavement cracks. He came to the conclusion that this cherished snapshot is fictional because he’s wearing Huggies in his recollection. “They weren’t invented in the 1950s when I was a child,” he says. “So it had to be wrong. If you reflect upon the details in these early memories, you’ll often find that they’re just not plausible.”

And we may not want to rid ourselves of these memories. Our memories, whether fictional or not, can help to bring us closer together. Brock Kirwan, director of the MRI research facility at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, explained that the act of reminiscing can act like a social glue, so that “shared experiences could help form the basis for your group identity and solidify group cohesion”.

A memory of a beloved grandparent or long-gone family pet can bring us happiness, whether it is fictional or not.

“I have one of meeting my grandmother and picking me up and swinging me around,” recalls Shaw. “It turns out it’s impossible, but for me it’s a wonderful memory.”

Surely a memory like that is worth hanging on to, even if it isn’t real.

Visits: 91