Tagline: If love is a game, who’ll make the first pass?

Oscar winners George Clooney and Renée Zellweger match wits in “Leatherheads,” a rapid-fire romantic comedy set against the backdrop of America’s pro-football league in 1925.

Clooney plays Dodge Connolly, a swaggering, aging football hero who is determined to guide his team from bar brawls to packed stadiums. But after the players lose their sponsor and the entire league faces certain collapse, Dodge convinces a college football star to join his ragtag ranks. The captain hopes his latest move will help the struggling sport finally capture the country’s attention.

Welcome to the team Carter Rutherford (John Krasinski), America’s prodigal son. A golden-boy war hero who single-handedly forced multiple German soldiers to surrender in WWI, Carter has dashing good looks and unparalleled speed on the field. But if Dodge thinks this new champ is too good to be true, then Lexie Littleton (Zellweger) can prove that’s the case.

A cub journalist playing in the big leagues, Lexie is a spitfire newswoman who sniffs holes in Carter’s war story. While she digs, however, the two teammates become off-field rivals for her affections. As the love triangle grows, Dodge fights to get the girl while he tries to keep his guys together. And if Connolly is certain of one thing…it’s that you always keep one final play from the defense. In addition to his duties as director and star, George Clooney serves as one of “Leatherheads'” writers.

Production Information

Academy Award winners George Clooney (Ocean’s Eleven series, Michael Clayton) and Renee Zellweger (Bridget Jones’s Diary, Cold Mountain) match wits in a quick-witted romantic comedy inspired by the stranger-than-fiction beginnings of America’s pro-football league in 1925.

Long before the days of jumbotrons, Astroturf and cheerleaders, multimillion-dollar paychecks and staggering endorsements, some men played football only for the love of the game. They were rough and crass. They were foul-mouthed and hardheaded. They were Leatherheads.

Clooney is Dodge Connolly, a charming, brash football hero who knows that this burgeoning sport is currently attracting, at best, a smattering of loud, drunk fans who can’t conceive of paying top dollar to attend an event. His games are free-for-alls that devolve into fisticuffs, and the situation is quickly deteriorating. But the captain is determined that it’s possible to guide his team and league to packed stadiums.

After the players lose their sponsor and the entire league faces collapse, Dodge convinces agent CC Frazier (Jonathan Pryce, Pirates of the Caribbean series, The Brothers Grimm) to secure his rising college football star, Carter “The Bullet” Rutherford (John Krasinski, television’s The Office, License to Wed)-who is filling stadiums with every game-for his ragtag ranks. Dodge hopes his latest move will help the struggling sport finally capture the country’s attention.

A golden-boy war hero who mythically (and single-handedly) forced multiple German soldiers to surrender in WWI, Carter has dashing good looks and unparalleled speed on the field. This new champ is almost too good to be true, and Lexie Littleton (Zellweger) aims to prove that’s the case.

A cub journalist sent by her editor to play in the big leagues, spitfire newswoman Lexie suspects there are holes in Carter’s war story. But as she digs, rookie Carter and veteran Dodge start to become off-field rivals for her fickle affections.

As the new game of pro football becomes less like the freewheeling sport he knew and loved, Dodge must fight both to keep his guys together and to get the girl of his dreams. Finding that love and football have a surprisingly similar playbook, he has one maneuver he will save just for the fourth quarter…

Clooney has double duty on Leatherheads, serving as both one of the stars and the director of the comedy, working from a script by first-time screenwriters Duncan Brantley & Rick Reilly. The film is produced by his partner in Smokehouse Productions, Grant Heslov (Good Night, and Good Luck., Intolerable Cruelty), and Casey Silver (Ladder 49, Hidalgo).

Down. Set. Hut. Leatherheads is Greenlit

Sports Illustrated reporter Duncan Brantley was researching the birth of the pro-football league in the late ’80s when he came up with the idea for Leatherheads. The journalist was digging into a story about star player John McNally, who ingeniously used the alias of “Johnny Blood” so he could play for the Duluth Eskimos in the burgeoning National Football League. This allowed McNally to play for the NFL without losing his eligibility for college sports.

The more he dug into the background of McNally and the other players of the era, the more colorful the characters who populated the sport became to Brantley. Indeed, their outlandish escapades fascinated him. After working on the script for several years, he brought colleague Rick Reilly on board the project, certain his humor would lend much to the script. Having spent many years together as S.I. colleagues, the friends felt they make a fine match as writing partners.

“We had covered college football for years at Sports Illustrated, and we were fascinated by this story of Johnny Blood,” recalls Brantley. “He was a wild man who loved to drink… and really did ride a motorcycle with a sidecar, as we wrote for Dodge Connolly.”

“The team played 31 games that year, and 29 of them were on the road,” Reilly continues. “Their owner was so cheap that he literally made them shower in their uniforms and then shower without them; then they hung the uniforms from the train windows to dry.”

It amazed them that often the teams would play four or five games a week, stopping the train if they saw a group of 10 or 20 guys that they could play for money. Though Brantley and Reilly had never penned a screenplay, the two veteran sports reporters had characters and a subject they loved, so they persevered. To add obstacle to their interest, however, Brantley lived in New York and Reilly in Colorado.

“At first,” Brantley recalls, “we locked ourselves in a room for about week and worked out an outline. Then we figured out which scenes each of us were dying to write and completed those. Rick would edit my copy, and I would edit his. Next, we literally leapfrogged through the rest of the script.”

“We knew the characters were so rich-like Red Grange and Ernie Nevers,” Reilly adds. “Plus, it was such an interesting period of sports history. For some reason, college football was really popular in the 1920s-they packed hundreds of thousands into those stadiums. But nobody cared about pro football-it was scandalous to play it, almost like, ‘How dare you play pro football? It’s not for gentleman; you’re supposed to go out and get a real job.’ Nobody really covered it before 1925, so we thought it was a unique and intriguing setting for a film.”

In the early 1990s, Reilly and Brantley brought the script to filmmaker Steven Soderbergh, who in turn gave it to producer Casey Silver, then president of production at Universal Pictures, who bought and commissioned it. “I was friendly with and a fan of Steven’s,” Silver recalls, “and had worked with him before and I liked the script- particularly in that it was a romantic comedy set in an arena that hadn’t been particularly explored in Hollywood.”

As the script went through various phases of development, Soderbergh would go on to direct Out of Sight, starring George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez. At this point, Silver had left Universal to become an independent producer, and the project went with him. “There were different iterations, different attempts to get it made, and it came together right after Out of Sight,” Silver recalls. “Steven wanted to do it with George. Steven showed him the script with my consent, approval and support and George responded.”

Clooney enjoyed Brantley and Reilly’s “premise of taking the star of college football out [of the university world] to make professional football big.” While he liked the story created by the writers, Clooney-a longtime fan of the comedies of ’30s and ’40s directors such as George Cukor and Lewis Milestone-felt the best version of Leatherheads would be “the Howard Hawks kind of comedy.”

Leatherheads would have to wait as the writer / director / actor focused on dozens of other projects for the next decade. In summer 2006, Clooney again turned his attention to Leatherheads and had another look at football star Dodge Connolly. By this time, Soderbergh had amicably withdrawn from the project, and Clooney considered it for his production company, Smokehouse Productions. The director offers: “About a year after Good Night, and Good Luck. and Syriana, I pulled out the oldest draft of Leatherheads.” He took a polish at the script, offering, “I basically used John Kerry’s Swift Boat as a routine-not in a political sense, but it was suddenly an idea of how to give this character a storyline.”

Clooney looked to the story arcs and comedy of “Philadelphia Story, of course, Front Page, Slap Shot and other films that I really love,” he adds. “Because it seemed like if you were going to do it, you really wanted to have those older themes-you needed a construct that we recognized from that era. Anything modern didn’t seem to work.”

With an ideal script and the time for him to complete the project, Universal greenlit Leatherheads, with Clooney agreeing to take the director’s chair and star in the comedy. The story that had started all those years ago on two sports reporters’ desks was now ready for production in spring 2007.

Commends Silver, “Despite making it look very easy for everyone else, George works very hard. His preparation is incredible. I thought Good Night, and Good Luck. was not only a very fine movie, but also a very well-directed one. It didn’t take much imagination to see that he could pull this off and handle it exceptionally well,” Silver says.

Of the challenges of deciding to direct himself in the film, Clooney reflects, “It’s a part literally written for me, and it’s a character that I knew exactly how to do. When I wrote Good Night, and Good Luck., I wrote the Murrow part for myself. Then as a director, I looked at it and thought, ‘Murrow always has this sense of sadness to him, this weight-burden on his shoulders-no matter what he does, even if he’s laughing.’ That’s not something people necessarily ascribe to me, and it’s not something you can act. It’s something you either have or you don’t.

“I realized fairly quickly that I wasn’t gonna be able to play the part I wanted, because I couldn’t play that part,” he continues. “I would have done it a disservice.

David Strathairn always had that quality. Dodge was one where I thought, ‘I’m dead-on the right guy to play this part; it’s square in the middle of me.'”

Clooney’s partner in Smokehouse, fellow producer Grant Heslov, says that the project interested him primarily for its originality. He notes, “I like period pieces in general, but what appealed to me was that Leatherheads was something we haven’t seen on film before. It’s such an intriguing period with such fascinating, larger-than-life characters; it certainly offered some unique cinematic possibilities. George and I both love all those Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder movies, and this certainly felt like it had elements of those great screwball romantic comedies.”

Heslov adds that three other films became touchstones for Leatherheads: The Sting, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Bound for Glory. The producer explains, “Those movies always felt authentic to the periods they depicted. They didn’t look too pretty or Hollywood, but they also felt very contemporary-in terms of the relationships and their stories.”

Script polished, director signed and lead male on board, it was time for Clooney and the producers to cast a number of thuggish football players and one gorgeous newswoman who could take everyone’s eyes off the ball.

Spitfires and Knuckleheads: Casting the Film

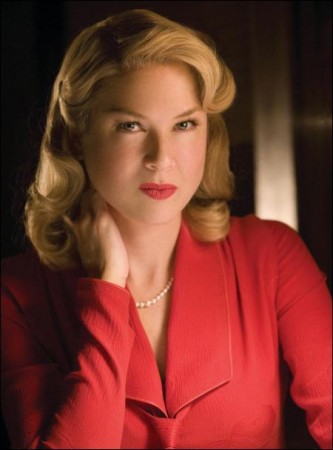

Choosing the comedy’s principals fell into place fairly quickly. Renée Zellweger, who plays sportswriter Lexie Littleton, caught in a love triangle between Carter Rutherford and Dodge Connolly, was one of the first actors to come onto Leatherheads. “George already had Renée in mind-her name was at the very top of the list,” says Casey Silver. “It was easy to get excited about her, obviously, because she is so perfect at romantic comedy.”

Grant Heslov adds, “She handles this rapid-fire dialogue brilliantly, and we knew she could play this feisty, smart character with savvy, sexiness and sophistication. What’s so great about Renée is that she also captures Lexie’s vulnerability, which comes into play when she has doubts about what she’s doing…and when she starts to fall for Dodge.”

Zellweger was attracted to the part because she found Leatherheads to be “the kind of movie you keep your fingers crossed for.” She responded to the fact that “it’s a throwback to those great old romantic comedies where the dialogue is sharp and witty, the story is compelling and interesting and the characters are full of color.”

The actor adds that what appealed to her about Lexie was the fact “she’s witty and smart, clearly a sharp girl who thinks on her feet. Lexie’s a bit of a spitfire, ahead of her time-but I also appreciated that she was very likable and, at the end of the day, has real integrity.”

Zellweger quickly discovered that, for much of the screwball comedy, the loquacious sports reporter utters mouthfuls of dialogue; the banter practically gallops among Lexie and Dodge and Carter. She liked that Clooney’s accommodating directing style made the rapid-fire lines much easier to manage. During rehearsals, they agreed that they wanted to catch each other off guard, and not become stuck in particular rhythms.

Zellweger offers, “We discussed the dialogue, the scenes, what the subtext was and how it worked in the story. But we didn’t over-rehearse; we never blocked out the scene to a great extent or ran lines too much. With these lines, that was easy to do, as there were pages and pages of dialogue. There was homework and memorization every night. But it was addictively fun, because the lines were so rich and we could take them in so many directions.”

Clooney expands upon his leading lady’s assessment of the script: “It’s like riding a roller coaster; it can’t all be brrrapppp, really fast. Going down is rapid-fire, and then you stop. You have to find those moments, and you find it through running the scene a couple of times and getting a rhythm for it. But Renée is the perfect actress for this; I can’t think of another that could’ve done it.”

John Krasinski came next, cast as football star Carter Rutherford. Producer Heslov felt that Krasinski understood Carter’s conflict as a war hero who might not be as valiant as first reported. The screenwriters had created a decent fellow not merely caught up in the hoopla of celebrity but, in fact, trapped by it. Heslov states, “We always saw Carter as basically a good guy-an innocent, smart man who got in over his head. John really got that and played it beautifully.”

Although Krasinski, best known for his work on the hit television series The Office, had been in a few feature films, he was impressed by the Leatherheads read. He says, “I read the script eight months before shooting, and I just loved it. I said to my agents, ‘This is the best script I’ve read in a long time. Let me know who gets it.’ But I met with George in his office, and we just talked; I didn’t audition, so that was amazing. About a month later, I went on tape. Two days later, they called; it was surreal.”

Krasinski had an affinity for the character caught between the worlds of war hero and football player, and agreed with the filmmakers’ take that Rutherford’s instant fame would make anyone more complicated. “We thought the key to him was that he had to be a really good guy who had a bad hand dealt. It’s not like he’s an evil person who’s been manipulating the situation and using his fame. He’s just a guy who got stuck with this. I focused on his innocence when I read the script, and it seemed like that’s what George honed in on too.”

When Krasinski was able to join the production, however, the company had already been filming in the Carolinas for about a month. Initially, he worked on the weekends; on the weekdays, he flew to Los Angeles to complete that season’s The Office. It was about a month and a half before he could join Leatherheads full time.

Award-winning Welsh actor Jonathan Pryce was cast to play Carter’s manager, the suave and cunning CC Frazier, a man with an equal eye for the ladies and the almighty dollar-initially somewhat of a mentor for the impressionable college player. Clooney and the producers wanted a Svengali who was smooth and sophisticated, a slick operator, but still not too oily. They felt the actor really knew how to walk that line.

On Clooney: “Jonathan makes it easy, because we know exactly who this guy is the minute he walks in the room. CC is slicker and smarter than we are, which Jonathan is; he’s smarter than anybody else in the room and has interesting instincts. And he’s also a professional who knows exactly what’s needed in the scene. When actors understand that, it makes it really easy to direct.” He laughs, “It’s embarrassing to act in scenes with him, but it makes him easy to direct.”

Pryce describes CC as “a guy who sees what he wants, goes in and gets it. He also thinks he has a chance with Lexie…with any woman. It doesn’t matter who it is!”

The performer found inspiration for CC in agents who had previously represented him; he relished the opportunity to channel them. “I’ve had agents in America who were CC figures, who had the eye on their main chance and couldn’t understand why I would want to play Macbeth for the Royal Shakespeare Company when I could do a movie- however crap the movie was,” Pryce states. “It was more important to make some money. Mercifully, those agents are in the past, but it was a lot of fun to play CC, where I could draw on their ruthlessness.”

As the movie is tethered to football, it was critical to cast just the right actors as the Duluth Bulldogs and their opponents, as well as an assorted rogues’ gallery of coaches, officials and reporters. As was the custom back in the day, the WWI vets, farmers and coal miners who comprised the Bulldogs all went by colorful monikers, such as Hardleg and Zoom. Key Bulldogs on Dodge and Carter’s team included Keith Loneker as running back Big Gus; Malcolm Goodwin as wide receiver Bakes; Tommy Hinkley as lineman Hardleg; Matt Bushell as Curly; Tim Griffin as lineman Ralph; Nick Paonessa as Zoom; Robert Baker as lineman Stump; Nick Bourdages as the waterboy with the foul mouth, Bug; and Rocky the English bulldog (a favorite of the director’s) as the laziest possible mascot.

Rounding out the core cast were seasoned character actors Jack Thompson as Lexie’s hard-boiled editor at the Chicago Tribune, Harvey, and Peter Gerety as Chicago Football Commissioner Harkin. Two O Brother, Where Art Thou? alums- Wayne Duvall as Bulldogs’ Coach Ferguson and Stephen Root as the team’s aptly named liquor-soaked sportswriter, Suds-also joined the production.

Suds spends most of the film inebriated or asleep, and Dodge ghostwrites the majority of his pieces about the Bulldogs. Laughs Root, “Suds is pretty much his namesake; he likes a couple. He’s good friends with his pal Dodge, the man who writes most of his stuff. He’s Dodge’s puppy dog-follows him around, does what he wants; they seem to be inseparable.” Of course, when Lexie Littleton appears, ostensibly to cover Carter Rutherford, Suds suddenly has some serious, charming competition-which he welcomes wholeheartedly.

In advance of principal photography, Clooney and the producers held casting calls for the football players and fans needed to populate the stands for games shot in Leatherheads. Hundreds of eager extras showed up, many more than the production required. The selected had to agree to have their hair cut in 1920s styles and, many times, were required on set before sunrise in order to be properly costumed and made up. Throughout production, they never lost good cheer, even when the mercurial weather patterns included wind, rain, freezing cold, glaring sun and blistering heat-sometimes all in the same day.

Many of the extras were high school football stars who had come to the casting call. Though Clooney, Krasinski and the boys knew they were matched with players who could easily best them, they were pleased to know that the screenplay dictated otherwise.

Learning the Game: Actors Suit Up

To turn Krasinski, Clooney and the rest of the performers into the Duluth Bulldogs, there would be much training on and off the field. Invariably, the new team would find itself playing football in swamps of mud in Greenville, South Carolina, while wearing scratchy woolen uniforms as the weather took one of her various phases-from blazing sunshine to plummeting temperatures when the skies turned ugly.

During two weeks of football camp, which occurred prior to principal photography, the guys learned to play “period football,” as well as how to execute plays that were both comedic and athletic. Coach TJ TROUP, a scholar of the period, onetime defensive back and longtime high school and college coach, led them through the paces. For the consultant, the trick was to help Clooney accurately depict early football, while also serving the needs of the story and the cameras capturing it.

Troup states that Clooney proved to be as prepared a historian as he was a filmmaker. “George shared some points with me on how he wanted the games to proceed,” the coach offers. “He and Grant had really done their homework on not only early football, but the subtle nuances of that era. My job was to tie all those pieces together. They wanted to ensure the authenticity of the plays, formations and stances, as well as how the game was played, because it was so much different.”

The free-for-all nature of the game in the ’20s made for a brutal experience for players of that generation. Troup explains, “The field had the same dimensions, but the philosophy and rules were different. For instance, there were no hash marks on the field. If a player was knocked out of bounds in 1925, the ball was placed one yard from the sideline. You had virtually the entire field to either your right or your left. And coaches in that era believed it was unmanly to win a game by passing. So, teams basically ended up in a rugby scrum where they would pound at each other, with up-the-middle running plays.”

That worked for these Bulldogs. Adds on-screen coach Wayne Duvall, “Back in the day, coaches were more like the managers of the team. They didn’t give the teams plays. In fact, they weren’t allowed to call them from the sidelines; that was a penalty. The players knew the plays and, in this case, Dodge was in charge of strategizing and executing them.”

The role of team captain was one Clooney took seriously both on-and off-screen. Duvall surmises the experience the whole group had with their director. He tells that Clooney’s style was not micromanaging, but more, “‘do that thing you do.’ If it’s not what he wants, he’ll tell you. But even better, there’s a real safety net with George; he gives you the liberty to make mistakes, but you know he’ll protect you from being a complete jerk.”

The ensuing camaraderie and team spirit that came from Troupe’s camp had its effect on Clooney’s men, with on-screen and off-screen friendships that continued throughout production. Notes the director, “They had plays they understood, so I could come out and step into a play and go, ‘Okay, here’s what we’re doing.’ You had to learn how to play differently, and you had to make it look mean-which is hard to do because you don’t have any pads. The guys all had to learn the plays-how to grapple yank. But we also put them in hotel rooms all together, so it was like a dorm in Greenville. They all spent time together, went to movies, hung out.”

Clooney had worked with several of the actors before, from Tommy Hinkley in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind to Keith Loneker in Out of Sight. While helpful to have familiar faces around when you’re being tackled or sacked during rain-soaked scenes, there was more than one occurrence when the director was hit in the back of the head with an errant knee or shoved into the unfortunately named “safety zone.”

Of all the teammates, the only one who had professionally played the game was Loneker, who portrayed overgrown high school student and formidable force of nature Big Gus. An affable giant, Loneker played for Kansas University before going on to join the Los Angeles (subsequently St. Louis) Rams and the Atlanta Falcons. The trouble for the athlete was “unlearning” his 21st-century football skills to convincingly play in the style of the 1920s.

“The stances are different-who to block, how to hold the ball, everything,” offers the actor. “Luckily, I’ve been gone from football long enough that I could still get in a bad stance. I’ve always played on the line, but dreamed of being a running back, so I was excited about that.” Director Clooney had other plans, however, and the brick wall was used to pound anyone who came near him, including the ref. Laughs Loneker, “Unfortunately, I never got to touch the ball!”

John Krasinski, due to shooting schedules with The Office, came late to football camp. He adds, however, that this already bonded group of actors welcomed him immediately. “I was completely aware of being the black sheep, the last one to come to football camp,” he recalls. “I felt like the evil stepbrother, but they were so incredibly open, very similar to their characters.”

The camaraderie came in handy during filming of the final game, which involved a week of playing football in, alternately, heavy rain and blazing sun on a field saturated with buckets of mud. Once they were in it, they were never out of it. Every day, the Bulldogs donned uniforms caked in muck and proceeded to dive, slide, wrestle, run and slog around. A team of makeup artists-armed with buckets of mud-stood in boots on the sidelines and prepared to run in to reapply to faces, necks and arms for close-up shots.

With extra pounds of mud stuck to the players, it was as if suction cups were on their feet. The hated slop would even become a key prop in an elaborate Clooney prank on the football guys-read: a fake shooting schedule, greenscreen, night work and a kiddie pool full of muck. Ah, football.

Locations and Design

Filming for the production began in South Carolina in February 2007. In early April, the company moved to North Carolina, where it completed the remainder of the shoot. Initially, Leatherheads was based out of Greenville, South Carolina, the home of a BMW test track. A cavernous, former BMW warehouse became home to the production office, the wardrobe and art departments and a few sets. Several tiny outlying towns provided locales for the rest of the South Carolina photography. The company was even more mobile in North Carolina, moving from Charlotte to Winston-Salem to Statesville over the course of a month and a half.

The Carolinas offered multiple attractive elements, as producer Grant Heslov points out. The most attractive of all was the production’s interest in not freezing to death. He provides, “The movie takes place in the Midwest, and football is obviously played from the fall into the winter. We needed that skyline, but we were also going to be shooting for a number of months. If we had gone to the Midwest in February to film these scenes, we would have frozen. The climate was more temperate in the Carolinas, though we did have our share of cold days and nights.”

Weather was not the only factor. “We also needed period trains and railroads,” he continues. “That’s how the teams traveled, and we had access to several of those in North Carolina. Additionally, we needed football fields that didn’t look contemporary, and there were several stadiums and schools that provided those settings and afforded us adjacent areas for support vehicles and trucks and trailers. Plus, there are film incentives in both states. All in all, it was ideal.”

The small towns in South and North Carolina generously supported the production. The tiny city of Greer, its storefronts virtually unchanged since the 1920s, allowed the crew to redress façades, even offering up one shop as a set. Leatherheads filmed there for several nights, virtually shutting down the village. In Statesville, North Carolina, where the production ended its journey, the company revamped the historic Vance Hotel, built in 1921; a scene was even rewritten to make use of the hotel’s subterranean swimming pool.

Across the street, the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque-style government building served as a set for several scenes, and the nearby civic center became the base for catering and support vehicles. Some of the sequences shot in Statesville required rain, so the special effects department lugged in rain towers, to the awe of the crowd of fans who regularly appeared to watch the goings on.

Throughout the Carolinas, the filmmakers found several stadiums that were built in the 1920s. The trick was to populate them with fans, especially as Carter Rutherford’s amazing plays and star quality begin to draw respectable crowds to the new pro-football league games. While more than 200 extras signed up to boo and/or cheer, the shots had to be designed with visual effects in mind. As the sport’s popularity increases throughout the film, so does the size of the crowd and stadiums. The art department would build the façade of a huge brick stadium entrance, for instance, but effects supervisor TOM SMITH and his department would augment everything in postproduction. While all this “digital football” was a challenge, it was made much easier by the elaborate storyboards Clooney used and made available to all the crewmembers.

Clooney film veterans, production designer Jim Bissell and costume designer Louise Frogley, were in sync with their respective specialties. This partnership was especially evident in scenes shot at the Calhoun Hotel in South Carolina. This 1920s era hotel was being converted into condominiums until Leatherheads persuaded the real estate agents to delay construction so that the production could film there. The Calhoun provided the setting in which our four principal characters-Dodge, Lexie, Carter and CC-meet for the first time.

Bissell’s selection of muted tones, vintage mahogany furniture and delicate wall murals-based on John Matthew’s illustrations from the 1920s-provided the perfect contrasting backdrop for Lexie’s entrance, arriving as she does in a knockout red dress. The impeccable Frogley designed the wardrobe to be as authentic as possible, and that meant using clothing and fabrics from the era.

On Bissell: “We wanted the look and feel of a classic comedy, as opposed to gritty realism-which meant controlling the palette. And in that set, in particular, the tones were very muted, but still authentic. The colors were of the period, and we tried to use real vintage products-from furniture to newspapers and graphics of the era.”

In all sets, while hues were subdued, there were always pops of color agreed upon by the design team. Renée Zellweger’s crimson dress and hat were reflective of the dyes available in that era and inspired by legendary performer Clara Bow. Adds Frogley, “George really wanted a red dress for that sequence. I worked closely with Jim to make sure the dress would work. It was successful, and she certainly made a memorable entrance.” Because the film was shot with a digital intermediate, Clooney would further be able to refine the contrasting colors of set and costume in postproduction.

Zellweger was well familiar with costumes of this period, as she had recently portrayed Mae Braddock in 2005’s critically acclaimed period drama Cinderella Man. “Louise has embraced a part of American history we don’t necessarily see often celebrated in films,” she complements. “With throwbacks to the ’20s, you sometimes imagine desperation and destitution-people throwing together what they can. She’s really celebrated the Roaring ’20s, where people were thriving and embracing the vivacity of American culture.”

For her men, the designer gave Clooney a wardrobe that moved from scruffy and “pretty beat up in the beginning” to classic woven fabrics that were “better when his fortunes improve.” Krasinski donned lighter-weight fabrics and slightly sportier styles, indicative of a bit of wealth from the era.

Costume and production design assimilated again on the football field. In the blunt cold of a winter field, the only color came from the scratchy woolen uniforms- often the Bulldogs’ trademark blue and gold-and the advertisements lining the stadiums. As Bissell points out, the signs helped the characters’ throughlines. “Commercial art is very evocative of the period,” he offers. “In Princeton, where Carter first plays ball, there are no commercial signs, because it is a college game. Then, at the Bulldogs’ early games, you see worn-out, local advertisements-even an old poster of Dodge at the entrance of the Duluth stadium hawking MoonPies.” As Carter (and the cash) start coming to the Bulldogs, national advertising starts pouring in and, says Bissell, “the money becomes huge, and the signs become almost cacophonous.”

For the meandering His Girl Friday-type newsroom at the Chicago Tribune, where Lexie reads her colleagues up and down and left and right, Bissell and Clooney made good use of the nooks and crannies, corridors and doorways to comedic and, sometimes poignant, effect. Not only does Lexie get her plum assignment there, she falls hard for Dodge in the office.

Perhaps the toughest production challenge was to build an interior train set (created to scale) that needed to replicate vintage locomotives that would have crisscrossed the country with Dodge, Carter, Lexie and the players. Bissell’s train sat on risers that rocked when Clooney needed to mimic motion on a railroad. It was complete with wild walls that could be moved and rearranged to accommodate a variety of shots and cameras, even one attached to the end of a crane. Toward the end of filming, the crew shot key interiors on moving, period-correct trains, courtesy of the North Carolina Train Museum.

Let’s Play Brawl: Football Camerawork and Sound

Not only was Clooney prepared with shot lists and storyboards, he was judicious with his angles and his takes. The day typically began at 7 a.m. and finished by 5:30 p.m. The pace was rapid, the mood was light and the director often completed impressive amounts of film setups per day. Clooney focused without losing his sense of humor or perspective, as both actor and director. The cast and crew grew accustomed to seeing him set up a shot in costume; often, after running the full length of the football field or receiving a nasty tackle, he’d appear at the video monitor to analyze the shot.

Filming football involved everything from Steadicam and dolly tracks to whizzing around the field on Grip Trix’s Electric Motorized Camera Dolly, affectionately known by the crew as “Trixie.” Much of the action was captured via ingenious rigs, invented on the spot by key grip HERB AULT. This kinetic, boisterous and physical work had to seamlessly meld with the film’s banter of the romantic comedy. Potentially, however, these two different genres could have been at odds. The key, says director of photography Thomas Sigel, was a distinct, unfussy cinematic point of view.

Sigel offers, “We are paying homage to the great, classic comedies of the ’40s- Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday, Preston Sturges-that kind of comedic oeuvre. George wanted to draw on the grammar of those films, yet not in a way that was replication, more as a reference. A lot of the camerawork is fairly static, set, composed frames- straight, lateral dolly moves. There’s not a lot of swooping cranes or cameras from objectives that are not the actors’ perspective. There are no strange oblique angles.

“Today, we have these tools to film football-cameras on the helmet, sky cams on cables that go flying through the action,” the DP continues. “There is an enormous range of what one can do. But we approached the football similar to the way we’ve set out to shoot the overall style of the film, which includes romantic comedy. A lot of the football is done with a fixed camera, or almost as if a newsreel camera was recording it, as in those days. The exception is that we have some tracking shots where we’re moving within the players, mostly when we want to feature Carter or Dodge. Even there, we’re doing tracking with a Steadicam on a car, but it’s not dissimilar to the way you saw them do certain kinds of tracking shots from the back of trucks in that time. It’s very straightforward, and it’s all totally from the characters’ perspectives.”

Production designer Bissell had to craft his sets with not only the camera crew in mind, but also with consideration for the sound mixer EDWARD TISE. The mixer faced sound challenges on the football fields-with the constant action of the game complicated by the expanding stadiums and the vagaries of weather. Tise couldn’t always rely solely on traditional methods to capture the conversations. Fortunately, as he notes, Tise also had good partners in the producers and director. Not huge fans of looping, they provided him whatever he needed to capture the sounds as they occurred naturally.

Relates Tise, “One problem with filming football, is that with all the physical contact, radio microphones [usually buried in the actors’ costumes] are not an option. One must rely exclusively on boom-mounted microphones-the placement of which are limited by the shadows they cast-and multiple cameras with wide and tight lenses of the same action that might also see the booms. It’s like having a 10-man sound crew.”

Additionally, Tise and team overcame these obstacles by being as light on their feet as possible. Instead of the bulky, heavy sound cart favored by most sound mixers, Tise used a lithe device he’d invented on a previous show. No bigger than a small laptop computer, the lightweight Aaton Cantar mixer/recorder was affixed to a wheeled tripod; they could now move around the field with dexterity.

The Yanks are Coming: Music of Leatherheads

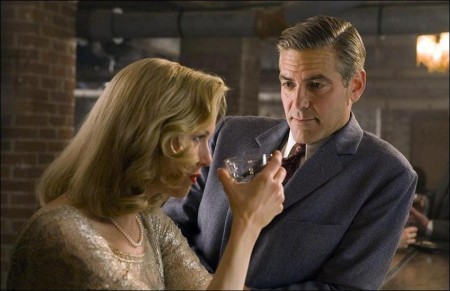

One of the highlights for the cast and crew occurred when filming a scene in a speakeasy. The set, literally underground, was in the basement of a sprawling government building called the Millennium Center in Winston-Salem, NC. The low-ceilinged, dark cavern with brick walls and exposed pipes was dressed with beaded chandeliers, filigreed, bronze sconces and the random deer head…all based on photographs of an actual Midwestern speakeasy, down to the mounted animals. This would be the beginning of the end for Lexie and Clooney’s attempt to fight their affections.

Add a bandstand and an upright piano, and the Roaring ’20s were back on stage for LEDISI YOUNG, a jazzy R & B singer whose vocals became the soundtrack for the speakeasy scenes. As in his film Good Night, and Good Luck., Clooney filmed Young’s live performance-here the classic tune “The Man I Love”-and used that as the playback for the rest of the scene. During the morning hours, the cast and crew crowded in the bar and listened as she performed.

The keyboard was for legend Randy Newman, who played an old-time, bar-room piano man. Newman’s job was to play ragtime as a bar fight raged around him, occasionally taking a break by blasting a roughneck on the head with a beer bottle. It was Newman’s pleasure, as the performer notes, “This period’s music is one of my favorites.”

Clooney also had an ear for serendipitous moments, such as Matt Bushell’s drunken, but heartfelt rendition of the popular WWI anthem “Over There.” For his character, the short-fused, pugnacious Curly, Bushell’s refrain is uncommonly sweet. “We were singing the song in between shots during a big scene where the team goes to a bar,” the actor explains. “Naturally, they get into a big, funny, drunk fight. George heard us and asked which one of us could really sing. One of the guys told him that I was the best singer. George said, ‘Get out of here!’ He then asked me if I could sing. I’m definitely not a professional singer, but I can carry a tune. We shot the scene right after that.”

The result was an unscripted, plaintive solo that caught the flavor of the time and the bond between the teammates. The director recalls, “I said to Randy Newman, ‘What if we just taper everybody out and do the last line with one guy?’ We did it in one take; it’s just stunning. You hear Randy end as the last, beautiful voice [Bushell’s] finishes the song out by itself: ‘We’re coming over, and we won’t come back until it’s over. Over there…’ All of a sudden, you felt like these are guys who were at war together. You hear Randy on the track say, ‘Man that’s beautiful.’ It’s such a great moment, and it came about because there’s something really beautiful about that camaraderie.”

****

Production wrapped, tendons bruised and bruises tended to, the filmmakers know the physical pain that was shooting Leatherheads was worth it. As prepped as they were for the inclement weather, hundreds of gallons of mud and an exhausting shoot schedule, however, they couldn’t plan for the aches and pains that came next. Dodge Connolly/Director George Clooney concludes with a sentiment shared by many of the thirty-and forty-something Duluth Bulldogs: “There’s just no way you could prepare for getting hit by a 21-year-old football player. Nothing you could do. It’s just, ‘Ow. That really hurt.'”

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Leatherheads

Starring: George Clooney, Renée Zellweger, John Krasinski, Jonathan Pryce, Stephen Root, Ezra Buzzington

Directed by: George Clooney

Screenplay by: Duncan Brantley, Rick Reilly

Release Date: April 4th, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for strong language.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $31,230,175 (76.8%)

Foreign: $9,451,474 (23.2%)

Total: $40,681,649 (Worldwide)