Tagline: Prepare for Awesomeness.

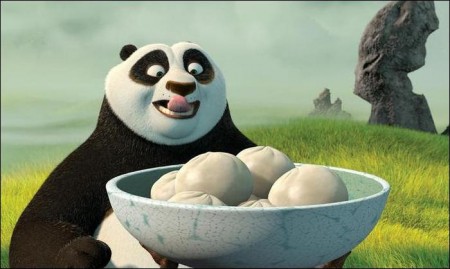

Enthusiastic, big and a little clumsy, Po is the biggest fan of Kung Fu around… which doesn’t exactly come in handy while working every day in his family’s noodle shop. Unexpectedly chosen to fulfill an ancient prophecy, Po’s dreams become reality when he joins the world of Kung Fu and studies alongside his idols, the legendary Furious Five — Tigress, Crane, Mantis, Viper and Monkey — under the leadership of their guru, Master Shifu.

But before they know it, the vengeful and treacherous snow leopard Tai Lung is headed their way, and it’s up to Po to defend everyone from the oncoming threat. Can he turn his dreams of becoming a Kung Fu master into reality? Po puts his heart – and his girth – into the task, and the unlikely hero ultimately finds that his greatest weaknesses turn out to be his greatest strengths.

Jack Black heads the voice cast as Po the Panda, the laziest of all the animals in the Valley of Peace. With powerful enemies at the gates, all hope has been pinned on an ancient prophesy that a hero will rise to save the day. But among all the martial arts masters who come forward, none has shown the mark of The Chosen One… until now. When Po unwittingly shows up in the midst of the competition, the masters are shocked to see that this unmotivated panda bears the mark. Now it is up to them to turn this gentle giant into a kung fu fighter before it’s too late.

About the Story

Enthusiastic, big and a little clumsy, Po (Golden Globe nominee Jack Black) is the biggest fan of kung fu around… which doesn’t exactly come in handy while working every day in his family’s noodle shop. When he’s unexpectedly chosen to fulfill an ancient prophecy, Po’s dreams become reality and he joins the world of kung fu to study alongside his idols, the legendary Furious Five: Tigress (Angelina Jolie); Crane (David Cross); Mantis (Seth Rogen); Viper (Lucy Liu); and Monkey (Jackie Chan) – under the leadership of their guru, Master Shifu (Dustin Hoffman).

But before they know it, the vengeful and treacherous snow leopard Tai Lung (Emmy / Golden Globe winner Ian McShane) is headed their way, and it’s up to Po to defend everyone from the oncoming threat. Can he turn his dreams of becoming a kung fu master into reality? Po puts his heart into the task, and the unlikely hero ultimately finds that his greatest weaknesses turn out to be his greatest strengths.

Also joining the international cast of “Kung Fu Panda” are Randall Duk Kim as Oogway, the wise leader and inventor of kung fu; James Hong as Mr. Ping, Po’s father and noodle maker; Michael Clarke Duncan as Commander Vachir, the proud mastermind behind the seemingly inescapable Chorh-Gom Prison; and Dan Fogler as the nervous palace envoy Zeng.

Becoming Your Own Hero

Whether it’s an ogre trying to regain what is rightfully his or a group of displaced zoo animals finding their way back home, audiences – of all ages – love to root for the underdog. Anyone who has ever struggled against the odds empathizes with the heroes in these entertaining and morally resonant tales.

So how about a panda who dreams of becoming a kung fu master? That’s right, a plump, drowsy, huggable black-and-white bear who has one, and only one, aspiration in life – to become an expert in a martial art that relies on agility, mental prowess and lightning-fast reflexes. It’s a formidable, some would say foolhardy, quest. But isn’t that what heroism is all about?

When directors John Stevenson and Mark Osborne and producer Melissa Cobb were presented with this unlikely storyline, they immediately responded. The obstacle- strewn journey of Po, the “Kung Fu Panda,” touched a chord in each of them.

Director John Stevenson begins, “We’re all parents, you know? I have two daughters and Mark and Melissa have kids. We wanted the film to have something that our kids could take away. `Be your own hero,’ which means don’t look outside of yourself for the answer. Don’t expect someone else to make things right. You are empowered to achieve anything you want, if you set your mind to it. Be the best that you can be.”

“It was important to all of us, from the start,” Osborne continues, “that `Kung Fu Panda’ would have a theme, a positive message that we really believed in. We wanted it to be a fun experience loaded with comedy and great action. But we also wanted there to be a takeaway that we all believed was a good one.”

Stevenson picks up, “So, in essence, we knew where we wanted to go, but perhaps even more importantly, we also knew how we wanted to get there. We were really aiming to craft a film that had a timelessness to it – while the story is set in our version of ancient China, the tale doesn’t only apply to those characters at that time. The greatest stories are timeless. And we clearly wanted ours to have that quality…a classic hero’s journey. Of course, the film would be entertaining, and fun, and the fighting will be cool. But our goal all along was not just to make one of those bright, shiny summer movies – we think Po and his journey, along with all of these appealing characters and inventive visuals, well, we were always striving to take it beyond that kind of film.”

In deciding that the tale of a panda pursuing his dream would provide both entertainment and a message, filmmakers were actually out to create a fable of sorts – and even the genesis of “Kung Fu Panda” sounded like the beginning of some ancient Chinese fable.

“I was directing a TV show at DreamWorks called `Father of the Pride,’” says director John Stevenson, a seasoned story artist and illustrator who previously worked with Jim Henson and joined DreamWorks in 1999. “While I was prepping the season finale, I was asked if I wanted to work on a project called `Kung Fu Panda.’ So, I went to look it over. I loved kung fu movies from when I was growing up in the `70s, as well as the `Kung Fu’ television show with David Carradine. I thought it would be an interesting challenge, so I immediately said, `Yes.’”

Stevenson says he was looking for an alternative to some of the more formulaic `talking animal’ movies of recent years. Something about the concept of “Kung Fu Panda” struck a chord with him. In many ways, it reminded him of the feelings that stirred inside him a decade earlier, when he was working on another project at PDI/DreamWorks – a film few had paid attention to (at first), but which also inspired a passionate commitment from its talent and filmmakers. That little movie was called “Shrek.”

A few years before “Shrek” was released and made animation history, another filmmaker named Mark Osborne had created a sensation at numerous film festivals with his stop-motion short film “More,” which garnered an Academy Award nomination and opened doors for the aspiring auteur. Notes director Osborne, “One of the doors that opened was at DreamWorks. I came in here as a director looking for a project and worked in development for a few years, making notes on projects and developing stories they weren’t sure what to do with. Then, I heard about `Kung Fu Panda.’ And I thought it was a great concept. I wrote some notes on the project and, after a while, they brought me in when they began to seriously shape the project. We already had the characters, some locations and some major concepts in place, but they weren’t quite sure the direction it should take. I saw it as a thrilling opportunity to jump into feature filmmaking and explore working with CG and a larger crew for the first time.”

That alternative storytelling point was also key to the film’s producer, Melissa Cobb. “We really wanted to do something different with `Kung Fu Panda,’” she says, “to make it stand apart from the other recent animated films. We loved a lot of those movies, but we wanted to break with what had become a trend and make a film that was more timeless. So, there weren’t going to be any pop culture references in this movie. Of course, it most certainly was going to be a family comedy, as well as an action-packed kung fu movie that was respectful of the genre.”

A Writing Pair on Extended Assignment

The journey to make the hoped-for timeless fable of “Kung Fu Panda” resembled somewhat the tale of the panda at the center of it all. The film had spent years in development, hardly piquing anyone’s interest. But with the production team’s zealous efforts, filmmakers had begun (metaphorically speaking) mining a rich vein – so rich, in fact, that the mine was overproducing. With this abundance of material, what was needed was a little specificity of product.

Enter two miners, um, writers, the talented duo of Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger. Jonathan Aibel explains, “Originally, what they had was great stuff. We just came on for a week to story consult, to help shape it. What scenes are needed and which ones aren’t? Are they in the right order? How can we focus the story? So, we looked at what they had and made some suggestions. That week became a month, and that month became three months, which became another 19 months – we just got so involved in the process.”

Per Glenn Berger: “It was an embarrassment of riches – amazing fight sequences, a lot of wonderful comedy. We were brought in to cut back the forest, to find the heart of the movie they were always aiming to make. But with such a beautiful world and fun characters, stuff had naturally grown out of that…the central story had gotten covered up. So we were there to help focus and tell the story everyone wanted told.”

And that story, all agreed, was about Po. So filmmakers convened several times to forge the story: Who is Po? What does he want? How does he get it? What happens? And how does it end? And all of this was to be decided without dependence upon a particular sequence or joke or set piece, to keep storytelling options fluid. And once that was agreed to, according to Berger, “That became the final say every step of the process. So at any time during the making of the film, and there came a disagreement on a certain element, no matter who it came from, we were able to ask some key questions.”

Aibel continues, “`Is it telling the story?’ If it is, great. So then, `Okay, can we expand on it-make it funnier, more dramatic, more action-packed?’ If it wasn’t telling the story, whether or not it’s funny becomes moot. This has happened on nearly every project we’ve worked on – they think it’s a great bit, and it is, but it doesn’t advance the story at all, so, it’s cut.”

And unlike Po’s belief in himself, the studio’s belief in the film remained constant throughout the lengthy development process. Bill Damaschke, co-president of production for feature animation and the film’s executive producer voices, “We knew that the film could be special. Throughout its development, we were frequently amazed by the talent and tenacity of the filmmakers in their pursuit of making `Kung Fu Panda.’ In a nutshell, we always believed in the film and in the filmmakers behind it.”

Producer Cobb asserts, “Jonathan and Glenn were a tremendous addition to the crew. They helped us to refine the story, make it really solid, and helped us find the characters and the tone of the project. They had a deep understanding of the characters early on and dove into the project with abandon.”

The film’s somewhat panda-paced development track changed when the studio experienced a momentous “a-ha!” breakthrough – of the big, light-bulb-above-your-head kind. Head of Character Animation Dan Wagner took a few sound bites of Jack Black’s and animated Po saying them. The marriage was an unqualified success.

Per Osborne: “Jack Black sort of tied everything together. He was ideal casting. I’m a huge Jack Black and Tenacious D [Black’s band] fan. I’ve always been really inspired by his work; he’s incredible. When he signed on, I thought, `That’s it!’ We said in the beginning that we wanted this to be a vehicle for Jack, and we really let him be the best version of Jack Black possible…which, you know, ties in thematically to the movie. It’s all about being the best version of yourself.”

Stevenson offers, “Jack’s a wonderful person – he’s just a great guy. And I think that you get that in his previous movies – even when he’s playing a very abrasive character. He’s always very funny and, despite how irritating his character may be, immensely appealing. And while he plays those kinds of characters exceedingly well, we wanted Po to be enthusiastic, likeable, eager…all of the best things that are almost always at the heart of Jack’s characters.”

One could have easily assumed that casting the accessible and hilarious Black for the project meant that “Kung Fu Panda” would move somewhere in the vicinity of a parody. But that was definitely not the case.

Director Stevenson explains, “One of the things that was important to me – and, I think, to everybody who ended up working on the film – was that we definitely didn’t want to do a parody, because everybody involved really admired martial arts movies. We all wanted to respect and honor those movies.”

“Kung Fu Panda” – which serves as the feature directing debut for both Stevenson and Osborne – was to be an exciting, animated kung fu movie, albeit one with plenty of laughs.

Osborne affirms, “An animated film is a huge labor of love, but it also is a huge labor, period. It takes years of work, probably about five years for `Kung Fu Panda,’ when all is said and done. So, it’s very helpful to have someone with whom to share the load. John and I work well together. And we actually ended up figuring out ways of taking different aspects of the project, to help split up the workload somewhat.”

Adds producer Cobb, “John Stevenson is a fantastic director. He’s been in the animation business for many years. He started out actually working with Jim Henson as a puppeteer, and has worked extensively as a storyboard artist on some amazing films. He came to `Kung Fu Panda’ with a commanding understanding of and a great attitude about the animation process. Having been through so many movies, he was always saying, `Trust the process. Trust the process.’ And that was really helpful. He had that sort of Zen attitude about directing the movie. `It’ll all work out in the end, and we just have to keep doing a great job.’ He was really very involved in the look of the movie and the design of the characters and constantly pushing the design team to challenge themselves, to take things further and to really explore where animation could go.

“Before Mark Osborne directed `Kung Fu Panda,’” the producer continues, “he had directed an Oscar-nominated short called `More,’ which, if you haven’t seen it, you absolutely should. It’s a spectacular stop-motion animated movie without dialogue, with amazing acting and an emotionally heartfelt story. `Kung Fu Panda’ is the first animated feature he worked on. Because of his stop-motion background, he really gravitated towards working with the animators and spent a great deal of his time on the movie working hand-in-hand with them. He understood, frame-by-frame, what they were doing in the animation process, and he became a great collaborator.”

From Cobb’s perspective, the two directors became the consummate team, melding their different backgrounds and tastes into a balanced sort of `yin and yang’ working style. The result? Per Cobb: “We went to great lengths to bring together the most talented writers, actors and artists that we could. Putting John and Mark at the helm resulted in one of the greatest working processes I’ve ever experienced. We put everything that we could into this film, and we hope that audiences love it as much as we do.

Screenwriter Berger observes, “There are a lot of different voices on a film, and it’s about getting everyone to share the same vision. It takes writers to write the scenes, expressing what needs to be expressed. It takes artists to render the scenes, actors to record the voices, animators to bring the characters to life, lighters, editors, composers to score…so at DreamWorks it really isn’t an autocracy, it’s about bringing all of these voices into unison.”

Aibel says, “And sometimes, that process is truly democratic. A town hall meeting with every say equal. The directors’ and producer’s job is then to listen to all of those voices and make sure they are telling the same story. It’s always a process of weighing what is being said and checking it against the unified story, and always keeping the audience’s experience in mind.”

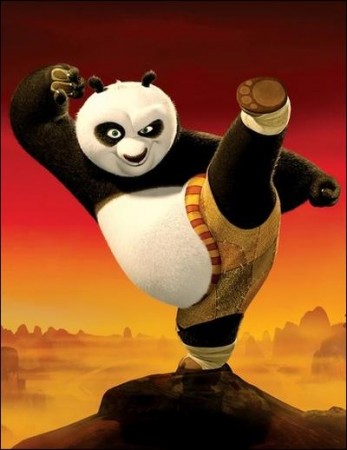

From the outset, the producer and the two directors set out to create “one of the best-looking movies this studio has ever produced,” which was less hubris than a goal inspired by the first two words of their title – kung fu. Though inexorably linked (in the Western mind, at least) to martial arts, `kung fu’ also refers to the excellence of self and its attainment through hard work. At its heart, “Kung Fu Panda” is about being the best `you’ that you can possibly be…to be your own hero.

This message underscored an important part of Mark Osborne’s life. The future director’s father had run car dealerships. It would have been easy for the young Osborne to head for the same career. “But instead, my father encouraged me to pursue a path that would make me happy, and paid to send me to art school. When I wanted to make my first animated short, my dad paid for it. My Academy Award-nominated short `More’ was funded by and produced by my dad’s employer, who saw an opportunity to help me achieve my dreams. So, the idea of being your own hero really resonates deeply with me.”

Once Stevenson and Osborne signed on to the project, they made a promise to themselves and the crew: “We were aiming as high as we could with this project-to make it everyone’s best. We set that as our goal and figured we’d see how close we could get. I think the animation in `Kung Fu Panda’ is some of the finest we’ve ever done, and Mark played a huge part in raising the bar when working with the animators, trying to go for a heightened level of subtlety, nuance, sophistication and reality,” says Stevenson. (One of their mottos was “If it’s easy or obvious, it’s not in the movie.”)

Osborne adds, “One of the things we thought would be interesting was to create broadly designed, somewhat `cartoony’ animal characters. But we didn’t want them to act in the usual `cartoony’ style. We wanted stylized characters who acted in a believable way…but could also be involved in some slapstick, `cartoony’ things – like dropping a character hundreds of feet and it wouldn’t die.”

Their aim was to find a visual language from which the filmmakers could transition from something as subtle as looking into the eyes of characters and sensing that they were conflicted, to a broadly comic situation, where someone gets whacked in the head and tumbles down a flight of stairs. The true challenge was to render both of these aspects believably in the same film, sometimes even in the same sequence. “Mark was a huge part of figuring out how to do that. And the fact that the animation is so good is, in large part, due to his leadership,” states Stevenson.

All involved are quick to point out that while “Kung Fu Panda” is a family comedy, it also boasts the same kind of action and adventure that made the martial arts films of the `70s such a pulse-quickening genre. Stevenson comments, “The basic comedic premise of our movie is in the title, `Kung Fu Panda.’ As a martial art, kung fu is extremely athletic and requires lots of self-discipline and physical ability. And pandas, well, everybody thinks of them as this soft, sleepy, roly-poly animal – probably the biggest, funniest and most cuddly creature you can imagine. Almost everyone involved in this project is a fan of those kung fu movies, and we all wanted to do a real kung fu movie… but we wanted it to be funny – the kind of funny that came out of character rather than from crafting a parody that made fun of the genre. With a panda learning kung fu, you get that. And each one of the Furious Five, Shifu, Tai Lung – are truly compelling characters. I think it’s funny and fast-paced, and tells a wonderfully touching story.”

Osborne continues, “There is a huge amount of heart in this project and it all comes directly from Jack Black. Early on, we were trying to understand why Po loved kung fu and wanted to be a kung fu hero, but kept his desires a secret from his father and the world. I found the inspiration from Jack’s band Tenacious D in their song `Cosmic Shame,’ since it’s about how important it is to follow your heart; that the key to true happiness is to pursue your dreams. Yet, the ultimate irony is that if you fail at your dreams, you fail big time. This was a perfect basis for Po’s inner conflict; he’d rather keep his kung fu dreams as a safe haven to escape to, than risk the `Cosmic Shame’ of trying to realize it and fail. If you go out on a limb, you can fall (especially if you are a fat panda) and Po doesn’t believe in himself enough to think he can make his dream come true. His accidental hero’s journey, however, ultimately takes him to a place where he must try with all his heart.”

Who Wants to Be A Kung Fu Panda?

When it comes to motion pictures – both animated and live-action – there is little doubt about Jack Black’s talent. He’s a gifted actor with enormous heart and he’s funny…really funny. Such hits as “Shark Tale,” “School of Rock,” “Nacho Libre” and “The Holiday” are evidence that his comic acting skills fit comfortably into a wide variety of projects.

So after his turn as Lenny the shark in DreamWorks’ “Shark Tale,” Black found that he had a voice fan in DWA head Jeffrey Katzenberg. Black relates, “I had a lot of fun working on `Shark Tale.’ One day, Jeffrey came to me and basically said, `Hey, let’s make another one.’ I had done a character voice, more of a nebbishy, New Yorker, kind of a Woody Allen-type of voice as Lenny. So I assumed I’d be getting back into the character voice thing. But Jeffrey said, `This time you’re the big cheese, and it’s called “Kung Fu Panda.”’ So, it was like, they wanted me… they wanted to hear the real me. So I thought, `Sure, I can do me.’ It was sorta like falling off a log into a recording studio.”

As for the character Black would be taking on, Stevenson observes, “If being a kung fu master is the highest pinnacle of achievement you can experience, Po’s right at the very bottom. He’s the exact opposite. Though he loves kung fu, he works in a noodle restaurant as a sort of waiter.”

Black explains, “Po’s father is a noodle chef and he loves noodles. But Po finds that all a little bland – he wants more excitement in his world – so he fantasizes about being a kung fu master. He idolizes those great kung fu artists like they were rock stars – they’re legendary in his mind. He’s ashamed to tell his father about his aspirations, because he knows how much it means to him that his son follow in his footsteps. So, he keeps it as a little secret. Also, Po’s a bit embarrassed, because he doesn’t think he really has what it takes to be a real kung fu master. So, he doesn’t want people to know about secret wish, because he thinks they’ll make fun of him.”

For Osborne, Black’s inherent qualities are carried through to his onscreen panda persona: “There is an innate sweetness and goodness about Jack that we really wanted to show through Po – a gentle, good-hearted innocent soul, someone who’s funny, appealing and charming – and we wanted the character to have all those qualities. It’s hard to imagine anybody more like Po than Jack.”

For Black, voicing a panda who’s crazy about kung fu isn’t too off the mark: “Kung fu has always fascinated me. The graceful gymnastics of a martial arts master are a thrill to behold. So when Jeffrey [Katzenberg] asked if I’d be interested in voicing the character of Po in `Kung Fu Panda,’ it was a very tantalizing offer. When I was a kid, I took karate and judo classes. It was fun and good for my muscles. I even won a trophy in a judo tournament… but I must confess I outweighed the competition by a good 20 pounds. Although I never took any kung fu classes – I just saw it on TV and in the movies – it seemed to me that it was the most spiritual form of martial arts. And Po reminds me of myself as a kid – he’s an innocent, chubby dreamer on a quest to find his destiny. There are so many wonderful characters, especially the little mousey kung fu master and instructor Shifu, voiced by my hero Dustin Hoffman. And the scariest villain since Darth Vader, Tai Lung, portrayed by Ian McShane. I was sold.”

Following the successful early voice/character test, Black was brought in to explore the character of Po. The first session was eye-opening, Osborne recalls. “During the first meeting Jack ad-libbed a lot and added things – all in the spirit of the sequence – that we had been playing around with. He brought this soulful and realistic quality to it. We took the session and started animating it. Right away, we saw we had a character with a great deal of appeal and likeability, someone truly genuine. The design of the film is beautiful and Jack brings so much as the central voice. The animation closes the deal by bringing his attitude and energy to the character.”

Casting Black was wish fulfillment for the screenwriters, but it also kept them on their toes. Jonathan Aibel explains, “We had come up with the idea of Po and then Jack Black was cast – so the character then evolved even more. We didn’t sit around and think up jokes. What we did was look back at the work we had done on the character and then watch what would come out of the sessions with Jack. Then we’d say, What did we learn about Po in that session?’”

Glenn Berger: “We’d go back and change the lines, based on this new aspect of the character that had started to emerge. And then poor Jack would have to record the scene for the 900th time, but maybe with subtle changes to reflect these new things we had learned about Po. So we were always in the `character development’ stage, because the characters grew with the actors’ performances.”

On working with his two directors, Black says: “Mark is kind of the arty one -he’s got arty roots, having gone to art school, he’s really well versed in…arty things. And John is really great with coming in and helping me focus on the emotional aspects of the story. He’s got mad chops when it comes to envisioning animal behavior, animal voices and characters. He’s got a lot of experience. And they both have great brains and great hearts and, together, they make a great team.”

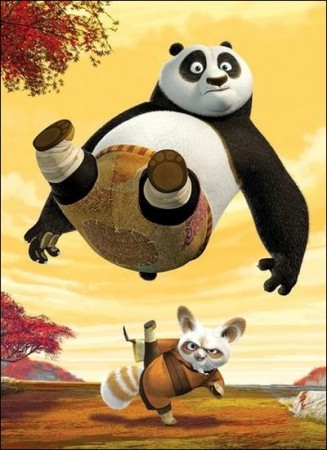

When the Student Is Ready, A Teacher Arrives

A great team is not what master trainer Shifu envisions when Po is plopped in front of him as the prophesied Dragon Warrior – that honor should have gone to one of his prize students in the Furious Five. So, the small red panda immediately sets about doing everything he can to get rid of the flabby panda. Melissa Cobb relates, “But because of Po’s great zeal with simply being where he is – in the presence of his idols, the Five, in the Jade Palace – he is too enthusiastic, too thrilled to give up. Their relationship is combative from the start. However, that ultimately changes when they realize that the stakes of the role of Dragon Warrior are much higher than Po had first anticipated. And so, we find two characters who really need to solve a problem together, but they just don’t know how.”

Shifu is not only short in stature, but also short on patience. To bring their two-foot-tall kung fu master to life, the filmmakers approached one of cinema’s finest actors, two-time Oscar® winner Dustin Hoffman.

“Shifu is actually our most emotionally complex character in the movie,” says Stevenson. “He has the biggest back story and probably the biggest emotional arc, because he’s sort of tormented by ghosts from the past. We knew Shifu was going to be a difficult and complex character, and it was going to require a really great actor to bring him to life.”

When Hoffman was approached, he was told he could make suggestions about his character. He remarks, “I liked the fact that they were looking at a collaborative way of creating Shifu. They would ask `How do you like the face?’ Well, I didn’t know much about animation – they put a video camera on you when you’re recording and they watch your gestures, and then construct the character and include little bits of your idiosyncrasies and gestures. I thought that was interesting. I made a couple of suggestions, because I’m very nose sensitive. Why, I don’t know. I wanted a little nose correction. I told them I demanded a nose change – I was just looking for a cheap joke. But they opened up the mouth and widened the teeth. I think that was their idea.”

Producer Cobb enjoyed the difference between Shifu’s size and the power that he wields: “What we loved about Shifu was that he’s really small but incredibly powerful. With a tiny little finger, he can completely stop Po in his tracks. And just to see that dynamic with a very small character exerting power over a giant character, you never feel the lack of that power. You always feel that Shifu’s in control, even against this huge character, Po.”

Hoffman found his job made all the easier by the direction he received from Osborne and Stevenson, who clearly had a specific sense of who Shifu was. “They promised me at the beginning that anything I didn’t like I could re-do – which you can’t do on a regular film. You have to hit it right the first time in live-action, like a high wire act – if you don’t, you hit the net, and they don’t go back, they just keep on shooting. These guys have spent four years on this, and they’ve always said that it’s constantly something you can change, you can re-animate. I allowed myself to be guided by them. Because otherwise, I would come in with some kind of predetermined idea that would be nowhere near as good as theirs.”

Later, when filmmakers showed Hoffman the rough cut, he reminded them of their promise – but Hoffman’s notes were negligible. “I was stunned that they had kept the character in line the whole time.”

From the directors’ points of view, Hoffman was always the perfect professional, always ready. “Every time we did a recording session with Dustin, he brought something extraordinary to the session and found a new way of coming at the lines that we’d never imagined,” says Osborne.

Director Stevenson sees a direct parallel between the actor and the character he voices: “Shifu is somebody that has an innate respect to him. And he’s very powerful. He’s very strong. He’s completely honorable, a disciplined character. At times, he’s pretty relentless and unforgiving. He’s a hard taskmaster. But he’s certainly someone whom everybody respects. So, it was very important that the actor playing Shifu be someone people would honor with respect. Dustin brings that, and also a certain gravitas.”

Hoffman and Black had the rare opportunity to record together (most sessions are solo, and actors rarely get to meet their onscreen co-stars). The mutual respect was palpable, with Hoffman noting that Jack and Po were pretty much one and the same.

Per Hoffman: “Every once in a while, an actor gets a role in life, where the director will say something along the lines of `Just show up and be yourself.’ Jack is perfect casting for Po. He’s very smart to use his comic gifts and not gild the lily. I was surprised when he showed up the first time and he was serious, like most wonderful comic artists you know. He takes it seriously and he’s marvelous in this.”

For Black, it was very much a case of art imitating life: “Shifu is the great master of kung fu, and Dustin Hoffman is the great master of acting. I remember, in high school, watching the video of his production of `Death of a Salesman.’ I watched it tons of times and I was just blown away by him. He’s just great as Shifu because he’s the master and he’s kind of Zen in his approach. He has a spiritual approach to his craft, from what I’ve seen him do in person. He comes from this quiet place inside. He’ll find the truth of the scene and just go after it in a real way…and he’s also just a little bit grumpy, just like Shifu. Perfect.”

Five Fighting Warriors

Po’s idols, the Furious Five, are all students of Shifu. They are superstars in the kung fu world – and Po’s heroes. They are the result of intensive, lifelong study at the foot of their master, and their level of fighting is unsurpassed in the land. They are the coolest, best action stars ever. They protect from harm the Valley of Peace and its inhabitants, who revere them as the incarnations of both power and spirituality, combined in five distinctive creatures.

When it comes time to pick the best among the Five – the choosing of the prophesied Dragon Warrior, a ceremony that happens once in a lifetime – the entire Valley (including Po) turns out to watch. This is a show of how central the Five are to the lives of every citizen in the land.

In keeping with the filmmakers’ reverence for kung fu, they chose their Five as animal incarnations of some actual fighting styles of the martial art. Osborne explains, “So we’ve got tiger style, crane style, snake style, mantis style and monkey style, all represented by those actual animals. Typically, in the past in a kung fu movie, you see a human imitating an animal doing those fighting styles, but this is the first time anyone’s ever actually seen these animals executing the fighting styles from which they derive their names – a fighter imitating a crane’s beak or imitating a viper’s tail. We get to use the actual animals and, needless to say, they do it very differently.”

The Tigress style is very direct and aggressive, and the animators brought those qualities to the character in their realization. Extremely powerful, Tigress uses a lot of upper body strength in her attack. She is a forceful character, opinionated, outspoken and direct. Many of the character’s finer qualities are embodied by actress Angelina Jolie in the role.

Osborne offers, “Directing Angelina Jolie is pretty surreal. I mean, she’s amazing. You have to kind of look away, you know? You can’t look at her directly while she’s performing, or your brain goes to mush. But what’s even more amazing about her is what she brings to the character. I mean – in all of our sketching, in all of our pretending, we were trying to work out the character on our own. But Tigress, on the page, was really a secondary character…but not with her in the role. She was complex and there were solid reasons for every choice. She brought warmth to the character. She didn’t just come off as the jilted contender who is angry at Po for being there and taking her place. She was supposed to be the Dragon Warrior, and because of Po, she isn’t. Her huge spirit and talents as a performer give Tigress all of these layers, and the character really expanded and grew deeper under her touch.”

High praise for an actress who, at first, wasn’t sure what character she would be playing. Jolie recalls, “When I first came in and saw all the characters, and I didn’t know who I was, I was secretly hoping I got to be Tigress. I love her. She’s cool. She’s secretly who we all want to be. If I were half as tough and straightforward as this character, it would be amazing. I have a giant tiger tattoo on my back, and my kids always look at it, so it’s very important that I be the tiger. So when I came in and saw the beautiful snake with the beautiful eyes, and I saw the monkey and all of the characters…they were all very cool. I thought Tigress was a boy when I first saw her and I thought, `I wonder who that is?… must be Jackie Chan. I guess I’m not gonna be the tiger.’ Then they told me and I was stoked.”

Jolie had many reasons for accepting the role of Tigress (in addition to the fact that she was really cool), and chief among them was her family. Jolie had voiced Lola for DreamWorks in “Shark Tale,” which she thoroughly enjoyed. “I just had such a good experience. It was so much fun to do, not just because I have children. That sounds like a really good excuse – `I do it for my children.’ But really, I’m a big kid. Animation has just grown and changed in the last few years and the stories are so good. This film was especially interesting to me because it was a sort of return to the classics. It’s like classic storytelling for children, and there aren’t a bunch of modern references. There are some beautiful messages and some really fun characters. There’s a sweetness to it. At the same time, the setting is absolutely beautiful. I love that part of the world. I have two children from Asia, so the fact that I get to be in `Kung Fu Panda,’ which is set in China, and I get to play a tiger, that is very cool.”

When asked if Tigress and Viper, the two females in the Five, are role models for young girls, producer Cobb muses, “If young girls are tigers or vipers, they’re perfect role models. Actually, what’s really interesting is that they are female characters and they have female voices, but we don’t isolate them in any way in the movie. They’re each one of the Furious Five. They’re just as important as any of the male fighters in the movie. They’re never given any diminished role because they are females. In fact, Tigress is clearly the strongest of the five characters.”

Jolie concurs: “Tigress is very straightforward. They explained to me that there are all different styles of kung fu, and hers is attack. There’s no defense. It’s just attack, attack, attack…so that makes her a very interesting character.”

While Tigress is all business, the character of Monkey is a bit of a cut-up. As a fighter, he is very unpredictable and playful. He uses his four limbs and tail in a fluid way, intending to distract the opponent, to trick him. And Monkey can use his limbs and tail simultaneously, plus he’s flexible and agile and, as a result, can lay a series of pummeling blows in a brief amount of time.

Who better to give voice to such a creature than international action star Jackie Chan, who combines flashes of good-humored wit with an undisputed mastery of martial arts? Melissa Cobb states, “We had to have Jackie Chan in our movie. I mean, he’s such an icon in kung fu movies, and the monkey character seemed a perfect fit. We had Jackie come in, and we pitched him the movie and showed him the characters. He was thrilled to see an American animation studio doing a movie about kung fu and he sensed the opportunity to really broaden the audience for kung fu around the world.”

Chan remarks, “For all these years, I’ve liked comedy. I use comedy together with my kung fu. I think it really fits me. And for all these years, jumping around and fighting, I’m just like Monkey. I think the writers and the animators have watched my movements, my characters, my…everything! It seems like they copied me, which is nice. Monkey is acrobatic, playful and confuses the enemy very easily.”

Chan even sees a future for himself combining what he does with an animated persona: “I hope, for the future, I can use animation with my action together – that would kind of make my action more `wow!’ Right now, animation is really something. They can make all these unbelievable things and put them into a fight sequence. And I really hope, someday, my action and DreamWorks’ technology will join together and take my action to the next level.”

While Monkey confuses, the character of Viper stealthily overtakes and overwhelms. Her style features sly, quiet surprise attacks and fierce and violent lightning-fast strikes. In “Kung Fu Panda,” it doesn’t hurt that Viper is beautiful and charming – another way to sneak up and distract her opponent. Then, by wrapping her body around the opponent’s striking limb, she forces the blow back onto the instigator.

Like Jolie, when Lucy Liu first visited the DreamWorks Animation campus, she was a bit uncertain about the project and distracted by the exquisite renderings on display before her – almost like one of her future character’s opponents. Liu remembers, “When I first came onto the project, they showed me a room completely filled with all these incredible animated images. And they had a computer version of what they had in mind for the different characters, including Viper. It all looked so incredibly rich and beautiful. They talked about the story, and I just loved the idea of the underdog having something he doesn’t know he has – great potential. It was exciting just to be part of a project like this and to play this character. When I saw the drawings of Viper, she had these two beautiful lotus flowers on top of her head. They didn’t really have to sell me hard on it, you know?”

Stevenson offers, “Every session we had with our cast, the characters gained depth and grew, even if they were just doing very small sections. It really takes a great and very game actor to be able to just dive right in and do bits and pieces like that. Every session with Lucy Liu was a blast. She’s great to work with and really talented.”

Despite the fearsome reputation snakes have earned, Liu admits that Viper is “quite lethal, but she’s actually quite sweet. She’s the first character to warm up to Po and have some compassion for him.”

Also like Jolie, Liu admits to being a big kid at heart, having grown up watching and loving cartoons. She still enjoys watching them with her godson: “And it’s astonishing, because you see what children see, which like this movie is so fresh and so wonderful. It takes you to a place inside yourself that is childlike, in which these characters become real people, part of your real life. And now animation is so technologically advanced and visually astonishing that, when you walk into the theater you can sit down and enjoy it like a kid would.”

If Viper’s style is compact, coiled and ready, Crane is her fighting opposite. In the traditional crane style, fighters use their hands in a beak-like way. Filmmakers made an early decision that Crane would not employ his beak when fighting – the effect might be a little too violent. Instead, they concentrated on some of the style’s other attributes. Crane is graceful and uses his enormous wingspan to deflect with sweeping gestures. Despite the beauty, Crane can and will still put up a good fight.

David Cross was cast in the role of Crane. His signature dry wit gave the elegant bird a distinctive voice among the Five. Crane also sometimes serves as the unwitting mediator among the group. Cross’s comic timing is wonderfully put to use, playing a slightly perturbed kung fu warrior who tries to keep the peace…even when he just wants to be left alone.

“I think Crane represents the Everyman,” says Cross, “or in this case, `Everycrane.’ Actors usually talk about seeing bits of themselves in their characters, but I have to be honest with you – I’ve never once thought of myself as a bird with skinny legs. An eagle, perhaps, or even an emu, but never a crane. And just for the record, I have great legs. That being said, I would admit that Crane’s voice is distinctly similar to mine. He’s very cool. So, I guess in that way, we’re alike. My kung fu’s far superior, though.”

While Crane is a laid-back dude, Mantis is one tightly-wound insect. Tiny and very, very fast, Mantis is also extremely precise – which renders him almost invisible. He can sneak up and pummel you without your knowing what’s happening to you. Precision with quick strike – meet Mantis, voiced by Seth Rogen.

“When they called me, I thought, `perfect.’ I’ve always wanted to play a mantis, so I thought it was oddly coincidental that they had called. And I was literally just talking to someone that day, saying, `You know, I never played a mantis.’ And then the phone rang and it was kismet, I guess,” says Rogen.

The producer chimes in, “Seth is amazing. We have this character of Mantis, who’s this tiny little bug. And throughout a lot of the development process, we thought no one’s ever gonna even see that guy onscreen. He’s just this tiny, little bug. And then we cast Seth, and his voice is so fantastic, his laugh is so memorable and so hilarious. And that laugh coming out of this little bug, it makes him a really memorable character.”

Rogen describes his first reaction to seeing his alter-ego: “He’s about six inches tall maybe, he’s got six legs and he looks a lot like me. If he had a bigger nose and glasses, we’d be almost identical. You know, I did karate as a youth. I think that plays heavily into my voice work here. I did karate at the Jewish community center in Vancouver for years. And I was good. I don’t know if I should gauge my actual karate skill based on a bunch of young Jews. On the grand scale of fighting, I don’t know where they rank. But I was pretty good at it.”

Rogen had met one of his co-stars before, having worked on writing an HBO pilot with Jack Black. So he feels safe when he proclaims, “Jack as a panda…it made sense when I first heard it. I could see that. I always thought somewhere down the line, one of his ancestors must have been a panda…a great, great, great uncle or something like that. Jack has panda-esque qualities, I guess. Actually, he’s great in the role; you can tell even in his voice that he’s relatable, friendly and open. And I actually think it helps that he kind of looks about 1/18th panda. It looks like there might be some panda blood in him.”

Something Wicked This Way Comes

What would an underdog story be without an antagonist? The beauty and sheer power of the Furious Five in action become evident in their face-off with the bad guy. With such strong good guys, the bad guy needs to be a truly menacing presence….and he is.

Tai Lung is that most dangerous of adversaries – physically imposing, ruthless, manically driven, brilliant and just this side of imbalanced. Take the most powerful fighter the Valley has ever seen and then imprison him for 20 years, where his dark heart can marinate in anger and revenge, and then set him loose to cut a swathe of destruction through the country where the inhabitants once thought him to be the shining hope of all.

Having voiced Captain Hook in “Shrek the Third” (and etched a memorable portrait of Al Swearengen, a villain of the Old West on HBO’s “Deadwood”), fans know that Ian McShane can be as bad as he wants to be.

Director Stevenson says, “Ian can go from zero to 60 in like 2.5 seconds. In life, he comes in as the nicest guy in the world. And then, when he becomes Tai Lung, he’ll just get behind the microphone and roar and make the hairs on the back of your neck stand straight up. He’s an amazing actor to watch.”

McShane can and does understand what Tai Lung’s problem is: “He believes he should’ve been the Dragon Warrior. He’s been denied it for 20 years, because pride comes before a fall, and that’s Tai Lung’s big problem – pride. He wants to reclaim his rightful place. Shifu put him in prison for these 20 years. But then, you know, it’s a moral story about believing in what you are but not ignoring the guy behind you, like the tortoise and the hare.”

Stevenson has been a fan of McShane’s for a while, having watched him over the years in his innumerable appearances in movies and on British television. And it just so happened that about the same time the director came aboard “Kung Fu Panda,” McShane had made the HBO series “Deadwood” an unmissable viewing experience.

And while McShane (as Swearengen) may have been involved in his share of knock-down, shoot-’em-up fights, he is glad that his “Kung Fu Panda” alter-ego does his own stunts: “I always enjoy playing a character that’s full of contradictions like Tai Lung – he’s not really a villain. He’s a complex character and he physically looks very good in the film. I mean, I’d rather I didn’t have to do any of the wonderful fighting that the characters do in this movie. I’d love to say that I could do that in real life. I’m just glad to supply the grunts and the groans.”

The timbre and gravity of McShane’s voice brings layers to the character from the first moment we hear Tai Lung speak. Says Mark Osborne: “What’s great about Ian is that he has this ability to really command the screen. Every line he says is incredibly memorable and powerful. And you get a sense of this really fascinating, angry, emotionally-wrought character, who’s coming to the Valley of Peace to exact revenge – and you get it with every word he says.”

Even if some of the citizens of the Jade Palace are convinced that Tai Lung can and will break out of Chorh-Gom Prison, there is one who does not – even as he’s watching the prison break take place: Commander Vachir designed and oversaw the construction of the one-man stronghold, built with the intention of keeping Tai Lung from ever rampaging through the Valley of Peace again.

“The Commander is a rhinoceros,” Duncan says. “Broad shoulders, big all over, muscular, probably can bench-press at least 5,000 pounds, fears nobody except for Tai Lung. That’s the one thing in the back of his mind he really does not want to deal with. I have a unique job. I have the most fail-safe prison in the world. I only have one prisoner and Tai Lung is his name. And he is very good, extremely good at martial arts. And I have a thousand soldiers on this one guy. One prisoner, nothing else, a thousand soldiers. And like I just told you, the guy is really, really, really good. I wish I could move like that.”

Duck Duck Goose

Mr. Ping, Po’s goose father, has no such kung fu wish. He is content being the owner, proprietor and chef of the most popular noodle restaurant in the Valley – a restaurant he hopes to one day hand down to his son. Mr. Ping is played by James Hong, an actor with a long history of playing a variety of amazingly different roles in more than 600 movies (everything from “Blade Runner” to “Mulan”) and TV shows (“Seinfeld” to “Law & Order”). As Po’s father, he has a great opportunity to create a quirky and interesting character who is so obsessed with making noodles that he really can’t see anything else. He probably doesn’t even recognize that Po is a panda.

As it turns out, Hong himself is actually the son of a noodle maker. Observes Osborne, “In our first session working with James Hong, he told us that his dad was a noodle maker and had a noodle shop. And so, as a kid, he was making noodles, and he totally understood the experience that Po is going through (though his family wanted him to be a civil engineer), and Po’s father as well (having firsthand knowledge of how to run a noodle shop).”

On the page, the character of Mr. Ping could come off as cool, maybe even a bit nasty. He works Po really hard and never takes the time to notice that his successful noodle making dream is not shared by his son. He loves his son, but doesn’t get to really show it. Director Stevenson says, “What James brought to the role is warmth. Po loves his dad and wants to take care of him, so he’s staying in the noodle shop and doing the thing he doesn’t love. He’s following his dad’s dream, because he really doesn’t have the courage to follow his own dream yet. It’s not until later that he finds that. His dad is actually a significant character in the end of the story, even though it seems like he’s holding Po back at the start.”

Po and Hong share a somewhat similar story: “I obeyed my father. I did my work. I went to college and graduated in engineering. And then, I became an actor. But during the engineering days is when the rebellion started. While I was in college, I started to do drama. But since I wanted to please my parents, I took up engineering, because that’s a solid profession. I graduated, finally, from USC as a civil engineer, making bridges. But that’s when my real ambition kicked in, just like with Po. I started to do extra work even when I was going to USC. By the time I graduated, I was getting roles, and I simply dropped engineering for acting. What kind of engineer could I have been? I don’t know. As an actor, though, I did pretty well.”

Just as Hong has had a long and productive career, so has Oogway, the ancient tortoise who invented kung fu as a means for the defenseless to defend themselves. The onetime warrior and now spiritual leader has dedicated his life to protecting those who can’t protect themselves. He has literally seen (and overcome) everything, and knows – deep in his soul – that there are no accidents… despite the fact that he is hanging the hopes of the Valley on the kung fu fighting ability of an out of shape, novice panda.

Master Oogway is played by Randall Duk Kim, an accomplished stage, screen and television actor, who found a whole new base of fans with his role as The Keymaker in the second installment of the blockbuster “Matrix” trilogy. The filmmakers were convinced that the actor could hold his own against Dustin Hoffman and also provide the weight and inner serenity that a 1,000-year-old prophet and spiritual leader would have accumulated.

Kim explains, “Oogway belongs to that tradition of an old, wise sage who helps the young hero – the same tradition that Merlin, in the Arthurian legends, belongs to. What attracted me to Oogway was his great wisdom, his age, his compassion, his kindness and his gentle humor. Having developed a martial arts form so the defenseless could defend themselves, he’s a protector of the small and the vulnerable. That kind of character is always attractive. Oogway is a character I can only aspire to. As I get older, I wish I could become someone like that – so compassionate, so patient, so understanding and kind. In our world, they are qualities to which everyone should aspire.”

Despite the fact that he’s a near saint in his Valley, Oogway also has a fun side, and some of his actions may prompt audiences to question his sanity, as in `is he senile, or just crazy like a fox?’ `Was his choice of the panda a universe-ending mistake, or does he really know more about the universe than he’s letting on?’ Says Osborne: “Oogway would never try to explain his methods, because you’d never understand it. Randall really connected with that. He was a great help in making Oogway significant. He’s an important character. He’s kind of a central anchor.”

“There was one line that reminded me of when I used to do tai chi and our teacher would use it during our meditation sessions,” recalls Kim. “It’s about the mind being cloudy and unable to see things clearly. When the mind is allowed to settle, to be still, things do become clearer and one becomes much more aware. Perhaps answers to difficult questions can be found within. That line made me remember and reflect.”

With Oogway at the top of the Jade Palace pecking order, the nervous goose Zeng is way down at the bottom. Zeng is an exhausted personal assistant to Master Shifu, who could be considered, well, a tough boss. That makes Zeng’s newest assignment all the more nerve-wracking: flying as fast as he can to Chorh-Gom Prison to alert Commander Vachir about Oogway’s vision of Tai Lung breaking free. Dan Fogler gives Zeng his anxious, `dear me, the sky is falling’-type voice.

Fogler enjoyed the mostly comic turn and found inspiration in some very old stories: “What did I like about Zeng? Like a lot of the characters in this film, he’s very classic. They seem to come from some alternate version of `Aesop’s Fables’ with kung fu added. Many draw from various character archetypes – Zeng is like a classic commedia dell’arte servant character, a bumbling servant who’s constantly put upon and sent across the world on errands. He’s always very nervous and trying hard to please everyone. But behind closed doors, he hates his existence, which is very fun to play. He’s also in the fowl family, and I grew up watching Daffy Duck and Donald Duck and all of the other characters who fall into that category. So, in a way, Zeng is close to my heart.”

Gathering such an amazing cast stoked the creative fires of the filmmakers and crew…and vice versa. Mark Osborne claims, “Whether it’s Jack or Dustin or Jackie or Angelina, or any of our wonderful ensemble of actors – they all brought different energies, but they always inspired us every time because of their commitment to their performances and the varied skills they possess.”

John Stevenson echoes the sentiment: “All the actors on our show are amazing. We had great experiences with all of them. And it’s actually good that we were in a soundproof booth away from them when they were recording, because we couldn’t stop laughing. We’d heard the jokes so many times, but often, the actors would bring ad-libs and they’d play around with the material in such a way that completely changed what we were doing. It was a real breath of fresh air in the process. One of the things about animation that is the most difficult to achieve is spontaneity at every stage. It takes great actors to inspire the animators, just as it takes great animation to inspire the lighters, and it takes great lighting to inspire all the finishing touches.”

Melissa Cobb adds, “I think it would be hard to single out just one actor who surprised us. I think there are moments in the recording sessions where each of them surprised us – they went to a place emotionally that we didn’t expect or brought something to a line, a bit of humor, that we didn’t even notice was there. And those are the really big gifts that come from doing those recording sessions and having the ability to really play with the footage afterwards and uncover the best performance.”

Just as the filmmakers praised their cast, the actors were equally surprised by the skills evident in their directors and producer. Lucy Liu sums it up best: “They had this incredible ability to invite all of us into this world they were making, and they brought it while you were sitting there in just a chair, or standing at the mic. That’s all it was – a room, a microphone, a chair, a headset, a glass. They painted this world around you with their voices and their imagination. They have the great talent to push you to get you to live in the movie, in the environment they created. It was special to be part of it, because you got caught up in it. Then the session was suddenly over and it was like, `Oh, no. Now, I’ve gotta go home and I won’t know what to do with myself!’”

Creating An Ancient World

For producer Melissa Cobb, it wasn’t only the film’s content that intrigued her, it was also the way in which Po’s story would be told: “From the very beginning, the directors really saw the film in CinemaScope, a wide-screen format. The CinemaScope frame, with its more expansive view, gave us the opportunity to make a much more epic movie, which was really consistent with the genre of kung fu.

It also really gave us a chance to explore the look of China. Our goal was to make a movie that had a distinct look, taking advantage of the latest technology in animation. One of the principles that we came up with early on was based on Chinese art- beauty in emptiness.’ We tried to be disciplined in the cinematography and the design. We wanted to maintain simplicity in the shots, to allow the eye to focus on the character and the amazing sets that had been created.”

Black wholeheartedly endorsed the filmmakers’ vision. “If you’re setting a film in a certain locale, it’s important to get it right. Not just because the people who actually live there might think, `That’s not how it is,’ but also because it’s interesting. It’s like if you really nail it, then the people who go to the movie are traveling to see that place as well. You want to take them somewhere specific and real and special. The way that they captured the beauty of the Chinese landscape and the architecture and artwork is mesmerizing. I have to admit that I’ve never been to China, but I imagine that when I do go, I’ll think, `Wow, this is just like “Kung Fu Panda,” kind of.’”

Director Stevenson explains, “We wanted the audience to feel they were getting a big story, not just big action, but hopefully big laughs and big emotion. We wanted a big canvas to paint our story on and CinemaScope was the best canvas to do that. The 2.35:1 aspect ratio of CinemaScope is, to me, what movies should be filmed in. Every kung fu movie that I saw growing up was in `Scope,’ because it’s a perfect format to capture huge, dynamic action.”

Director Osborne continues, “The epic kung fu films have all used CinemaScope. It provides a broader view of the world. And you can actually tell a more intimate story in CinemaScope as well, which seems sort of counter to the idea of this very wide, broad view. But you can tell an intimate story because it allows you to get in really close and tight with the character. At the same time, you’re also getting the entire environment around that character.”

Production designer Raymond Zibach and art director Tang Heng began research early in the process to put together the look of the film. Key to everyone was that it be inspired by Chinese art, landscape and architecture and would be, in its own way, true to Chinese culture. In a tale where creatures are dressed and gifted with a mastery of kung fu, it was important to ground the film in some kind of truth. The aim throughout was believability and cultural richness. As a result of these months of intensive research, the film is filled with details that probably only the trained eye may detect.

As production designer, Zibach is in charge of all visuals – from character to location to color to the styling of the whole film. He began exploratory designs about five years ago, mostly with animals and natural structures. He worked with character designer Nicolas Marlet to design the creatures in a somewhat semi-human way, to allow them to do kung fu. The team embraced classic Chinese palace and temple architecture.

Per Zibach “This film has a charm and individuality, which is different from what everybody else is doing in computer-generated film. When we took what we’d done with our characters and put it next to something traditional like the beautiful architecture of China, it actually showed off our characters even more, lending to the whole fantasy of `Kung Fu Panda.’ I think that this contrast created a whole different feel for what a CG animated film can be.”

Zibach shied away from lifting actual Chinese locations and copying them exactly out of respect for the Chinese and their culture. Their aim was to embrace the essential beauty and put it together in a way that felt right for the film. The choice of clothing design for the characters – though Chinese in inspiration – had less to do with historical accuracy than with allowing each character to perform kung fu and fit spatially into the overall design canvas.

As the design landscape began to fill in, some elements began to take on a greater significance. The earlier script dedicated just one line to the Jade Palace, as a room within a larger compound where Po stayed for a night. Once they began to use the “jade” in Jade Palace as an overall design, the richness of the growing design – featuring elements such as jade bamboo – prompted the filmmakers to increase the importance of the environment. The Palace became one of the main locations, which gave the artisans an even greater reason to make the space grander.

The outdoor locations were heavily influenced by the look of the Li River Valley and the city of Guilin on the west bank of the Li. Zibach explains, “We wanted to take the sugarloaf spires which are beautiful, rounded green, lush rock spires from the Li River Valley and crank them up. Tang Heng, our art director, took that idea to a legendary scale. Also, we wanted to try to keep everything very rounded where the villagers appear. So all the villagers and their shapes are heavily based on circles – which creates a nice, rounded, pleasant and happy feel. When the action turns more dangerous, things get more pointy and angular. So, that simple shape theory really ruled the overall design.”

Art director Heng joined the project when the film had begun to find its storyline, and some of his first exploration heavily influenced the look…so much so that those pieces became the equivalent of a `reference book’ that was consulted throughout production. Zibach praises his efforts. “I think of Tang much more as a partner, because what he brought influenced me, and I hope vice versa.”

Visual Effects Supervisor Markus Manninen was responsible for the visuals in collaboration with Zibach. The prospect of a CG action film excited Manninen, as did the visuals and the earthy story. “It’s something everyone can relate to and it’s the kind of movie I like to watch myself.”

Acknowledging the ever-present limitations in filmmaking – resources, budget, time constraints – Manninen was amazed at everyone’s commitment to unearthing the smartest way to tell the story, even if that way seemed impossible at first. Dedicated craftsmen spent time researching whether that hoped-for part of the scene could be done in a smarter way – giving the film a bigger bang for the buck or producing something extraordinary that had never been seen before.

Key to producing those extraordinary onscreen moments was the involvement of Hewlett-Packard, which proved integral to the animated artistry displayed in “Kung Fu Panda.” Says Manninen, “HP is a fantastic partner, to the company and the studio. For us, it was crucial. About midway through production, we discovered that some of the things that we were trying to do were just really difficult to accomplish. Some of the latest HP hardware really saved us. We were at the borderline of not being able to execute some of our scenes and this, actually, helped us achieve the kind of production value we wanted for the movie.”

Heng was given the opportunity (with a team of artists) to assist in creating and developing the look and style of the film. Since the film is set in China, the goal was to create an ancient Chinese world where animals and vegetation, everything, lived in harmony. As a reference point, Heng studied ancient pottery, with much of what he found taking root in his work with the team. “I help visualize the directors’ and the production designer’s visions. After we’ve talked about the setting and the environments I spend two to three weeks designing a visual concept to illustrate their thoughts. Then we look at it together and make the necessary adjustments to finalize it.”

In addition to consulting sources on Chinese mythology and architecture, Heng and others viewed lauded Chinese films, like “Hero” and “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.” Since a majority of the artists came from Western culture, it was important for them to absorb as many Eastern influences as possible.

Some discoveries surprised Heng: “One of the coolest ideas about the Chinese architecture, I believe, is that it is designed after nomadic tents In the ancient days, these tents were designed to keep rain from pooling on the top. The shape of those roofs still has an influence on the shape of the roofs in Chinese architecture today.”

Not only shape, but colors with Chinese significance were incorporated – gold is for the emperor and red is for good luck. They turned out to be the two main colors that were used in the film. The Valley, of course, is heavy with green (green is a color for good), and Tai Lung’s world is awash in blue (a cold color, since he is, after all, a snow leopard).

Heng and his staff also consulted with Xiaoping Wei on both Chinese culture and architecture, on a sort of `fact-checking’ basis; in addition to being a DreamWorks artist, Wei is one of Hollywood’s top experts on all things Chinese. Early designs that featured Asian designs outside of traditional Chinese looks were questioned – and replacement Chinese designs were chosen.

Breathing Life Into A World of Characters

Po’s journey is transformative and, in the end, his efforts are revealed to the citizens of the Valley. In a similar vein, the creation of Po and a legion of unique and beautifully designed characters is for Nicolas Marlet a story of recognition. The accomplished character designer and Annie Award winner has been with DreamWorks since the studio’s early days, having worked designing characters for the studio’s animated debut, “The Prince of Egypt,” and on the character design of the subsequent “The Road to El Dorado,” “Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas,” “Madagascar” and “Over the Hedge.”

But with his work on “Kung Fu Panda,” Marlet has been given a singular honor for his designs, the ultimate sign of accomplishment for an artist. Typically, characters undergo countless iterations until they work perfectly within their specially created world. With Po, Shifu, Tai Lung, the Furious Five…Marlet’s initial designs have not been altered since they were crafted – what is seen onscreen is what he originally created. From creation to final touches, the characters remain as Marlet envisioned.

Per director Stevenson: “Nico [Marlet], the character designer, did a great job. He does a very traditional animation style of drawing with these great circles the animators do to follow through on their shapes. It worked perfectly for what we needed for the character design, and his creations stayed as he gave them to us.”

Head of Character Animation Dan Wagner was charged with establishing the style of animation for each character – how they move and how they behave. Part of that meant finding ways to ensure consistency with the characters Marlet created. Wagner smiles, “Having furry animals kick each other’s butt is a fun idea. So, for a start, we brought in someone with zoological training, a bio-mechanist named Stuart Sumida, who’s very knowledgeable on how animals are put together and how they move – he’s helped us on other films in the past. We had a few classes with Stuart, going over each of our specific animals, just how they operate and how they behave – also, their bones and muscles, how they connect and work together to bend and move.”

For characters’ facial expressions, Wagner could look to `lipstick cam’ footage, captured during the actors’ recording sessions, but he usually opted for folding the expressions and mannerisms of the actor into the character, rather than trying to re-create the expression exactly.

What lies beneath the garments and the characters’ features and appearance is the domain of Character TD Supervisor Nathan Loofbourrow, who takes a sculpture of the character in a neutral, standing pose, and then lays in a skeleton, muscles and skin to create a puppet (called a “rig”) for the animators to use.

Working on animals is commonplace for Loofbourrow, but the cast of “Kung Fu Panda” was an altogether different animal: “The mantra we heard at the beginning of the production was that every character had to be able to do kung fu. So, that meant pushing the performance further than we were used to doing – quick moves, strong fighting poses, all the stuff that fans of the genre want to see characters do in an animated kung fu movie. Because of that demand, we really had to push rigs to be able to hit more dynamic poses, to execute really exciting, fast action. And, of course, we wanted every character to look good while doing it, which was our biggest challenge.”

It’s already a tall enough order for the athletic Furious Five and the diminutive Shifu…but a 260-pound, out of shape panda? Loofbourrow solved that problem by using Po’s big torso as a sort of shock absorber that would allow him to retract and extend his arms and legs – when that happens, his belly moves and creates a bit of dynamic motion. By creating volume, Loofbourrow provides Po with the ability to do kung fu maneuvers and yet remain mobile and flexible.

Loofbourrow comments, “It’s really exciting for us to see kung fu done with animals onscreen. It was a unique project for us. We hadn’t been asked to do anything like this before. So, working on such challenging characters was really enjoyable. We had a small team that worked a long time on the film together…and just knowing everybody’s work is up there onscreen makes us all really happy.”

A Prison Break, A Bridge Collapse… and the Ultimate Dumpling

Once production had ramped up and all departments were moving forward, it was time to start on some of the big action set pieces that punctuate “Kung Fu Panda.” First up – Tai Lung’s near impossible escape from Chorh-Gom Prison.

“We knew it had to be special,” says Osborne, “because it sets up the character of Tai Lung, who is this legendary, unstoppable warrior – the most accomplished and feared kung fu master in the world. This sequence was going to serve as our signature, to tell people that we had amazing kung fu in our film. So it had to be good – and cool and exciting.”

The superhuman nature of the escape clearly shows Tai Lung taking on every adversary and beating them all at once. Anyone witnessing this would surely have one question in mind: how is a big, fuzzy, soft panda going to beat this guy? That was the other purpose of the scene, to enable the vengeful snow leopard to cast a fairly long shadow through the second act of the film. His approaching threat needed to remain in people’s minds without filmmakers adding scenes flashing to Tai Lung’s progress.

A super-sized sequence was needed…and meticulous storyboarding went a long way toward ensuring the breathless action it demanded. Daniel D. Gregoire (an expert in pre-visualization who worked on “War of the Worlds,” “X-Men: The Last Stand” and “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull”) developed a “pre-vis” of the sequence, which proved helpful in determining the dynamic camera movement and transforming the feel of the scene from an animated action scene into a cool, live-action set piece.

Per Gregoire: “We had very specific ideas for the scene. It was designed as almost like a video game. We had given it an epic setting. We knew it was going to be a prison break. But then we thought, `Okay, if it’s a prison break, it’s got to be the craziest prison ever seen – it can’t be just a regular prison.’ So, we designed a prison to hold just one prisoner, because that is entirely in keeping with Tai Lung’s character.”

The prison is carved out of a mountain in Outer Mongolia. The design is a blend of influences, notably the 18th century Italian artist Piranesi, who executed studies of fantasy prisons, mixed with battlement designs lifted from the Great Wall of China (the battlements are on the interior of the prison, however). Add to that the video game feel achieved by sectioning the prison into security levels: first level, crossbows; second level, bridges with armies of fighting guards; and the last level, equipped with a ceiling that collapses on the upper tier – a last-ditch effort to contain the prisoner.

As Tai Lung battles upward, more than just the composition of the levels change – so, too, do the color palettes of the scene. While the escape pits snow leopard against innumerable guards, it also pits the colors of blue against red. Blues, grays and purples are Tai Lung’s colors, which give the feeling of a wintry chill perfect for a lethal snow leopard. Reds and other hot colors are traditionally associated – in the Eastern and in other mythologies – with power and strength, the warmth of the sun, the waving of flags over battlefields. As the prison forces are vanquished by the snow leopard, the defeated level shifts in color, from red to blue (as the lights are extinguished). This is a visual signal that accompanies Tai Lung’s progress and telegraphs the possible wintry chill that will fall over the Valley of Peace should he prove ultimately victorious in his quest.

Says Raymond Zibach: “The original concept was of a vertical prison. But because of video game-play, I had to question, `How do you we make it interesting for Tai Lung to get up and out of the prison?’ So, we ended up designing a lot of bridges for the archers and an interesting way to get down. Then I thought that an elevator would be a great way to cut off the lower level from above, and it would give a safety barrier that reassures Vachir that he has an insurance zone, that there is no way that Tai Lung could get up those sheer rock walls. I think those obstacles were interesting solutions, because I had never done a vertical sequence like that before. It ended up being very inventive, plus it built up our bad guy right away. It shows that he’s got smarts and he’s got talent.”

That talent is very much in evidence in a subsequent battle between the Furious Five and Tai Lung. Mark Osborne comments, “I think the bridge fight is one of the coolest kung fu fights ever put on film. It’s really exciting to say that about an animated sequence, because while I’m sure it’s extremely difficult to make a kung fu movie in live-action, in animation it has its own challenges. We have amazing artists and technicians who really helped create, rig and build these characters in such a way that they actually have all the ability needed to make the fight as spectacular as it is. The sequence is complicated for many reasons: our characters have fur, our characters wear clothing, plus they’re doing kung fu and fighting on a disintegrating rope bridge – all of it is extremely complicated.”

Angelina Jolie says she was quite impressed with the sequence: “It’s amazing action. I underestimated what it was going to be. I’m not just pleasantly surprised, I’m really excited. Anytime I’ve done a film where I have to work on a stunt, you practice it and you try to find the best ways to do something interesting. I think the best stunt sequence is when the audience watches it and can understand everything that’s going on – they can really follow the details of the stunt. At the same time, they are seeing things they’ve never seen before. And everything is used in the most extraordinary way. But, to see the bridge fight, and to see everything that they thought to do on this bridge, and all the different styles of fighting from the different animals, and how they put it together in a really clever way…it was so much more than I anticipated, and really well thought-out, really beautifully done, and really funny, in between, too.”