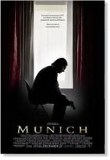

Critics

You never want to be labeled a fan of Israel in today’s Hollywood.

Mimi Weinberg: With Jews like Spielberg we don't need enemies.

Gila Almagor says thriller about Israeli assassinations of Munich 1972 massacre perpetrators will improve country's image.

Spielberg tells Time Magazine ahead of release of upcoming movie about Munich Olympic massacre.

Interviews

Audiences will be challenged by the complex moral issues that it raises.

"We're all kind of directly responsible for you know, most of the pain that goes on in this world."

Reviews

One thing critics agree on about Steven Spielberg's Munich: it will give audiences something more than popcorn to chew on.

A film of uncommon depth, intelligence, and sensitivity, Munich defies easy labeling.

As Steven Spielberg ponders the pointlessness of tit-for-tat retaliation between Israelis and Palestinians...

Steven Spielberg successfully enters Costa-Gavras territory with "Munich".

For aspiring Israeli actor Guri Weinberg, the big break in Hollywood was mixed with heartbreak.

|

Munich widow blasts Spielberg Munich widow blasts SpielbergMimi Weinberg lost her husband in the Munich massacre, but unlike other bereaved families, she's never gone public about the incident. Now, in an exclusive interview, she pulls no punches as Steven Spielberg's take on the tragedy is set to open in Israel.

LOS ANGELES – Mimi Weinberg has never told this story before. She's always left it to the other 11 families who lost loved ones at the Munich Olympics to give media interviews. She's remained quiet.

"My mental health wasn't great," says the widow of wrestling coach Moni Weinberg. Now, she has broken her silence in an exclusive interview with Ynet, ahead of the Israeli release of Steven Spielberg's Munich.

A year-and-a-half ago I got a call from Spielberg's office. They asked me if I could go on camera and talk about what Golda (Meir) told me a few days after we finished sitting shiva," Weinberg remembered.

"At Moni's funeral I asked IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar to arrange a meeting with Golda for me. Then the phone rang, and she sent a private driver for me. She greeted me in the Prime Minister's Office in Jerusalem with a drawn face, fiddling a piece of paper between her fingers.

"'I have a problem speaking to widows, orphans and bereaved families,' she told me. 'This is not for publication, but I have given instructions to do away with all of them, even the commanders.' "

Golda comes through

Weinberg says she thought Meir was just trying to get rid of her. "I couldn't believe it," she says. But a short time later, hints started appearing in the media. It was then Mimi understood that Golda was keeping her promise.

"One day I was going to the supermarket near Golda's house in Ramat Aviv. One of her bodyguards motioned to me to stop and said the prime minister wanted to speak to me. She stuck her head in the window and said, 'I made a promise to you, and I intend to keep it. But don't tell the media.'

To this day, I've never told anybody. Not even the other families," she says.

Spielberg did a lot of in-depth research and managed to unveil this story, and asked Weinberg to talk about her meeting with Golda that day in 1972.

"I demanded the right to read the script before I agreed to cooperate," she says. "They said 'no,' so I said 'no.' I think they wanted to open the film with me and Golda."

Weinberg may have refused to cooperate, but her son Guri, an aspiring actor, couldn't say no. At age 33, he bears a striking resemblance to the father he never met, and who died at the age of 33.

"Moni was at (Guri's) brit (circumcision ceremony), but left immediately for Munich," says Mimi. "I never told Guri about the tragedy. I had a hard time talking about it. My parents told him."

Hollywood-bound

They moved to LA in 1986, to give Guri a chance to realize his dream. He went to high school in Beverly Hills with the likes of Angelina Jolie, Jennifer Aniston, the grandkids of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, and others. Now, he plays his father in the movie and appears in the opening minutes. Moni was the first to be killed. The part has no words.

Mimi: "Nobody really knows what exactly happened in Munich. All I know is that Moni came home from a performance of 'Fiddler on the Roof,' and because of this the terrorists got to him first. They forced him to knock on the doors and he brought them to the wrestlers' and weightlifter's room, thinking they would resist. Moni was killed first."

For years she has been furious that no moment of silence was held for the victims, and she doesn't believe Spielberg's film goes far enough.

"I watched the Golden Globe film awards all tense. When Spielberg and Kushner failed to win anything, I jumped for joy."

Why?

Because they produced a fantasy. That a Jewish producer and director never bothered to call (former Mossad Chief) Tzvi Zamir or anyone else to learn about what really happened. None of us were invited to premiers in Hollywood or Israel, because they were afraid we'd speak out.

"The American media wanted to interview me, but I refused, because anything I had to say, for better or worse, would have plugged the movie. I don't want people to see it, even if my son is in it.|"

Weinberg is critical of Hollywood for equating the terrorists and the Mossad.

"This movie fails to discern between those who murder innocent civilians in their sleep and those who hunt down the murderers. That's what frustrates me about this movie. It drives me crazy. I saw the movie twice. The first time I couldn't believe what I'd seen, so I went again to make sure I understood.

"With Jews like Spielberg and Kushner we don't need enemies. There are so many children who never knew their parents. People are murdered in their sleep, and along comes Spielberg to cause the Americans to believe that this is some sort of reality."

Toughest part

Guri Weinberg's contract forbids him from being interviewed about the movie. But he did tell Ynet about his the difficult feelings of stepping into his father's shoes during the final, dramatic moments of his life.

"I've heard stories about my dad my whole life, but they were just words. When you play him, the whole thing somehow becomes real," he says. "It's like a bad dream. I was on the set and it was as if someone else were there. It's hard for me to explain. Most of the time I was in shock. It was hard to feel my own body."

Guri heard stories about how his father tried to save his own life from a young age.

"I was angry with him for many years," says Guri now. "I thought that if he hadn't tried to fight them, maybe I would have had a father. When we were filming the movie, I understood for the first time that he had to do what he did, and that he had no chance to get out of there alive."

City of dreams

Los Angeles is a city of dreams. For every actor there are thousands of waiters and waitresses waiting for a break.

"It's a very tough business," says Guri. "Until now I've played small roles, a few bigger roles on TV, but as a result of appearing in Munich, I have professional interest. Its funny – this is the hardest role I've had to do - my own, personal tragedy. But now I'm in demand, I've got a ton of auditions. Life is funny."

On the set Guri learned more details of his father's murder.

"All sorts of people told me stories about how he died. For example, I never knew he was shot three times. I'd always heard he was shot twice. It's tough learning these sorts of details about your own father, when you're on the set of a movie and have to be strong, professional. I didn’t want anyone to see me break down on the set. I played my part and went back to my hotel room. That's when I cried."

There is one more thing Guri Weinberg wants the public to know: "The Arab actors were very nice. They told me they abhorred what happened in Munich and they wanted me to know it. The one who shoots me in the movie, Karim Saidi, started crying immediately after Spielberg yelled 'cut,' and came over to hug me."

- Yitzhak Benhorin

|

|