Tagline: The only thing that could come between these sisters… is a kingdom.

Based on a novel by Philippa Gregory, “The Other Boleyn Girl” revolves around the ferociously ambitious Boleyn sisters, Mary (Scarlett Johansson) and Anne (Natalie Portman), who are rivals for the bed and heart of 16th century English King Henry VIII (Eric Bana).

A sumptuous and sensual tale of intrigue, romance and betrayal set against the backdrop of a defining moment in European history, “The Other Boleyn Girl” tells the story of two beautiful sisters, Anne (Natalie Portman) and Mary (Scarlett Johansson) Boleyn who, driven by their family’s blind ambition, compete for the love of the handsome and passionate King Henry VIII (Eric Bana). While both women eventually share the king’s bed, only one will ascend to the throne for a brief and turbulent reign that ends tragically with a swing of the executioner’s sword.

When rumours begin to circulate that King Henry VIII (Eric Bana) is no longer intimate with his wife who has been unable to give him a male heir, Sir Thomas Boleyn concocts a plan to bring his family back to prominence: his daughter Anne (Portman) shall seduce the King and provide him with a son. However, the scheme goes off course when the King takes to the other Boleyn girl, Anne’s younger sister and best friend Mary (Scarlett Johansson).

Although married already, Mary gives in to family pressure and reluctantly provides the King with a boy, but along the way, she finds herself falling in love with the surprisingly tender monarch. Of course, this love affair is no obstacle for Anne whose hunger for the throne now overpowers her sisterly love, and she enacts a plan that eventually tears her family and her country apart while leading to her legendary demise.

About the Production

Based on the best-selling novel by Philippa Gregory, The Other Boleyn Girl is an engrossing and sensual tale of intrigue, romance, and betrayal set against the backdrop of a defining moment in history. Two sisters, Anne (Natalie Portman) and Mary (Scarlett Johansson) Boleyn, are driven by their ambitious father and uncle to advance the family’s power and status by courting the affections of the king of England (Eric Bana). Leaving behind the simplicity of country life, the girls are thrust into the dangerous and thrilling world of court life — and what began as a bid to help their family develops into a ruthless rivalry between Anne and Mary for the love of the king.

Initially, Mary wins King Henry’s favor and becomes his mistress, bearing him an illegitimate child. But Anne, clever, conniving, and fearless, edges aside both her sister and Henry’s wife, Queen Katherine of Aragon, in her relentless pursuit of the king. Despite Mary’s genuine feelings for Henry, her sister Anne has her sights set on the ultimate prize; Anne will not stop until she is Queen of England. As the Boleyn girls battle for the love of a king — one driven by ambition, the other by true affection — England is torn apart. Despite the dramatic consequences, the Boleyn girls ultimately find strength and loyalty in each other, and they remain forever connected by their bond as sisters.

About the Story

To their father, Sir Thomas Boleyn, Anne (Natalie Portman) and her younger sister Mary (Scarlett Johansson) are precious commodities whose personal lives must be carefully managed so as to yield maximum financial and social benefit for the family. Convinced that Anne has the potential to attract a suitor of superior standing, Sir Thomas turns down a marriage proposal from a merchant family and offers them Mary instead.

Sir Thomas soon sees a golden opportunity to exploit Anne’s beauty and wit when his brother-in-law, the Duke of Norfolk, arranges a visit to the Boleyn household by King Henry VIII. Aware that Queen Katherine has been unable to produce a male heir and Henry is on the prowl for a mistress, Thomas instructs Anne to do her best to make a favorable impression on the monarch. Henry is immediately intrigued by the brazen young woman, but Anne proves too headstrong for the ruler,who turns his attention instead to the sweet-natured and equally lovely — though recently married — Mary.

Deeply enthralled, the king summons the entire Boleyn family — including mother and father, Norfolk, both Boleyn sisters, and their brother,George — to the Royal Court for the express purpose of making Mary his lover. Sir Thomas and the Duke of Norfolk are delighted at this turn of events — and even Mary’s passive husband dutifully agrees to the dubious arrangement — but Mary, a simple country girl at heart, has no interest in the life of a courtier. Anne, still stinging from the king’s rebuff, seethes with silent anger toward her sister. , Taking her future and fortune into her own hands, Anne elopes in a forbidden, secret marriage, but this is quickly discovered by Mary, who informs the family. They send Anne to France, banishing her from Henry’s court.

Despite her initial reluctance, Mary soon finds herself deeply in love with the tender and attentive Henry. She becomes pregnant with Henry’s child, and all is well, until her difficult pregnancy confines her to bed rest and the king’s romantic interest in her wanes. When Sir Thomas summons Anne to return to court to entertain the king, it is the moment Anne has been waiting for. Just as Mary and George find their positions at court starting to slip, Anne, still bitter, plots to seduce the king and to exact revenge for what she sees as her sister’s unforgivable betrayal.

First, Anne taunts her sister over the long-held grudge and persuades Henry to cast Mary and the newborn child out of court and back to her destitute husband in the country. With Mary out of sight, Anne begins to play out her clever scheme to become not only the king’s mistress, but his queen. She withholds sex from Henry, demanding that the king annul his 20-year marriage to Katherine, send her away, and marry Anne. Henry demurs — because divorces are not allowed within the church, such a move would require a split with the Pope and likely spur an invasion.

When news of Anne’s brief secret marriage surfaces, that one loose thread threatens to unravel the entire plan. The calculating Anne calls upon the only person she knows she can count on, summoning Mary back to court. Mary, seeking peace with her sister, tells Henry that he can trust Anne, and the king, convinced by the other Boleyn girl, marries Anne, who is now pregnant with his child. Anne has won — she is crowned Queen of England.

But Anne’s victory comes at a high price. Henry’s controversial marriage to Anne proves more than simply a scandal in court; the repercussions of Henry’s split with Rome push England to the brink of war. The king is left feeling disgusted with himself and his new bride, and with the eyes of the world on his court, Henry knows he can avoid humiliation only if Anne produces a son.

When Anne’s first pregnancy results in a girl and she covers up the miscarriage of a second pregnancy, the king’s patience with the Boleyn family reaches an end. Anne, Mary, and George, at the mercy of a vengeful king and a pitiless court, are stunned when their father and uncle sacrifice the children in an attempt to save themselves. In the end, with the executioner’s sword waiting for Anne, there is no one but Mary willing to speak for her, and this time, even Mary’s words cannot save her sister. Nevertheless, it is the unending bond between sisters that becomes Anne’s final solace.

About the Film

In her bestselling novel The Other Boleyn Girl, Philippa Gregory spins a new take on a very old story: the ill-fated romance between King Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn. With a twin focus on Henry’s relationship with Anne as well as his illicit affair with Anne’s sister, Mary, Gregory’s novel portrays the court of the Tudors as a home for sex, intrigue, and power games.

“I think before I wrote the novel, hardly anyone knew about Mary Boleyn,” Gregory says. “She was a character hidden from history, maybe because historians weren’t interested in her, because she made no difference to the historical record. But I saw her story as a contrast between sisters, and that contrast was fertile ground. It becomes a parable for the way women make use of their opportunities.”

For director Justin Chadwick, the central relationship in The Other Boleyn Girl is not necessarily the famous one between Henry and Anne but the one between Anne and her sister, Mary, who vied with her for the king’s attention. “Anne and Mary do some terrible things to each other, there’s rivalry and jealousy between them, but ultimately, they’re sisters,” he says. “You have a relationship with your sister that’s different from any other person. You have conversations behind closed doors, talking to her in a completely different way. You can be completely open and honest with her. Like Mary says, it’s like being two halves of the same person.”

Of course, sisters can be horrible to each other, as well. “This is like a mafia story in the court of the Tudors,” says producer Alison Owen. “It’s got sex, rivalry, jealousy, ambition, scandal — with sisters at the heart of the story.”

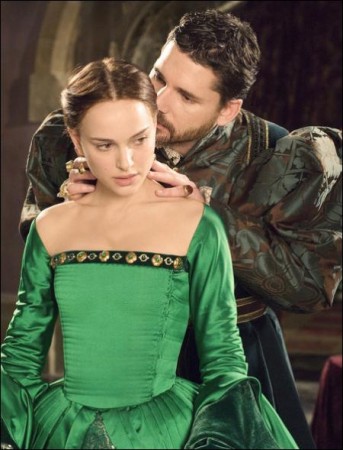

Chadwick found his Boleyn sisters in two award-winning actresses, Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson. “They brought something to the roles, some sibling intimacy, some closeness, that meant we could take scenes further than the written page,” he notes. “During the course of the film, the sisters’ relationship changes, but they remain tied together as sisters. Natalie and Scarlett portray that beautifully.”

Portman takes on the role of Anne Boleyn, who would replace her sister as the king’s mistress, becoming his queen. “It’s easy to see the story for its place in history, but at its heart it is a family story, a story between sisters,” says Portman.

Johansson plays the “other” Boleyn girl, Mary, who would happily fade into history. “Sibling relationships are complicated,” she says. “Everyone can understand that jealousy and competition. The bond is very strong; only your siblings can read you so well and know instinctively how you feel.”

Of course, when a sibling rivalry is placed at a pivotal moment in history, the stakes are raised and the risks and rewards are both great. Chadwick notes, “We start with three innocent children, Anne, Mary, and George Boleyn, and chart their journey from a country field to the throne to the scaffold. Their lives go horribly wrong through ambition and greed. The nastiness and intrigue will speak to a modern audience, as a reflection on obsession with celebrity and a warning to be careful that you don’t lose your head, in their case literally, over your ambition.”

Peter Morgan, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his screenplay for The Queen, was eager to adapt Philippa Gregory’s novel for the screen. “Though I’d already tackled Henry (for an award-winning television drama starring Ray Winstone), I became hooked when I realized that this was a story from a completely different perspective,” he says. “It’s written with such energy and gusto and the two sisters are such fantastic polar opposites. Anne is a proper 16th Century diva — strong minded, stubborn, and manipulative — who accomplishes one of the great historical seductions, and manages to withhold her favors from the most powerful man in her world till she gets what she wants. She is the family favorite, in pole position, and needs the limelight. Mary is much more complicated; she has a higher emotional intelligence, an inner spirituality and is quite feisty and unbending in her own way.”

“Whichever sister becomes the more successful in their rivalry for the king’s affections, the other one becomes the `other’ Boleyn,” Portman says. “Anne totally buys into the whole competition, while Mary chooses a way to be happy without life in the court, and she ultimately wins by allowing Anne to have the victory that destroys her. It’s a family story, with love and intrigue, about children who are corrupted by a world which pushes them to compete rather than support each other. Mary, the survivor, is the one who rejects that world.”

Joining Portman and Johansson are Eric Bana as King Henry VIII, Kristin Scott Thomas as Lady Elizabeth, rising star Jim Sturgess as George Boleyn, Mark Rylance as Sir Thomas Boleyn, and David Morrissey as the Duke of Norfolk.

To bring the motion picture to life, Chadwick called upon a team of specialists, including Emmy-winning production designer John-Paul Kelly and two-time Oscar-winning costume designer Sandy Powell. The film also employed an etiquette advisor, Noel Butler, to give special insight into the customs and mores of the royal court.

Summing up his experience, Chadwick says, “I want the audience to believe that there might be hope for Anne, even though everyone knows her fate. I hope they’ll follow the twists and turns of the story and wish that Anne gets a reprieve.”

About the Cast

Oscar nominee Natalie Portman says she first approached the role of Anne Boleyn with research. Relying not only on the character as written in the novel but also on historical sources, she found that Anne was a woman both of her time and ahead of it. “Anne had a sense of self-respect that was uncommon for a woman of her time. She thought she deserved a status she was not born with, and this ultimately led to her demise,” she says. “Marriage then was not about love; it was about uniting families to increase their power. Anne accepts this, but the unexpected thing is that Henry is charming, handsome and educated. She finds him an intellectual companion, and her way of attracting his attention is to challenge him.”

As an only child, Natalie relied on her co-star for insight into sibling relationships. “Scarlett is one of four children. I felt like I had a co-conspirator — she’s a wonderful actor and a very playful person. Peter Morgan agreed that in every scene there were 20 things going on between the girls — loving, fighting, feeling guilty, rivalry, but above all closeness.”

Johansson also researched the period before playing the role. “It’s interesting to read about life at the Tudor court,” she says. “As the rest of the world was suffering, fighting religious wars and wars for land, the royal court was its own little world.”

Still, Johansson’s main research tool for background on her character was the novel. “Not much is known about Mary’s life,” she explains. “You can read different versions of how the affair with Henry came about and nothing is known about her personality. There were no articles written about her, no public interest in her. She was just another of the king’s mistresses. So the best research material I had was Philippa Gregory’s imagining of this person, and that was incredibly helpful to me.

“The Boleyn girls are written as two halves of the same person. I think that is always true of sisters of a similar age, even if they don’t always want to admit it,” Johansson says. “What Mary admires and is repulsed by in Anne are traits that she wishes she had herself. Similarly, Anne comes to realize at the end of the story that she wishes she had some of Mary’s traits.”

Johansson was also gratified by the opportunity to work with Portman. “This can be such a competitive business, and it is rare to have two such strong roles for women in one film,” she says. “Natalie is kind and generous, personally and in her performance. She is inspiring to work with.”

For Chadwick, one of the exciting prospects of The Other Boleyn Girl was the opportunity to show King Henry VIII as Anne and Mary see him — powerful, charming, and sexy, so different from the way he usually appears, as an older man. “Philippa Gregory had written about Henry as the handsome and intelligent man he was before the madness set in,” he says.

To portray the young king, Chadwick looked to Eric Bana. Bana has a well-established Hollywood career, but surprisingly, it was his background in improvisational comedy that appealed to the director. “Eric is a handsome movie star, but his improv experience allows him to show the warmth and humanity of this man who was king of England.”

“My wife had read the book, as had many women I know, as I later discovered,” Bana says. “I think women are so attracted to it because it shows two very strong sides of the female psyche: in modern terms, Anne is the professional, ambitious woman, while Mary wants love and family. I love Philippa’s writing — it is very vivid, full of tasty and unsavory characters.

“What appealed to me was the complexity of the man,” Bana continues. “I felt that even when he behaved badly, there was logic to it that I could understand. By the end of the film we can see where he is headed — he’s becoming a spoiled brat, unpredictable and dangerous. In a sense, he’s leading a double life — he’s one man in full view of the court, but behind closed doors, he is mesmerized by Anne.”

Bana has high praise for Portman and Johansson, calling them “two freakishly great actors. They are two incredible wells of ability and emotional range. I was in awe watching them work. Having watched their careers progress, it seems bizarre that they are both so young. The sisterly relationship evolved so effortlessly.”

Oscar nominee Kristin Scott Thomas plays Mary and Anne’s mother, Lady Elizabeth Boleyn, who tries to protect her daughters while also ensuring their success in life. “The question of survival, for women, came down to marriage,” she notes. “How `well’ you married meant that you would have somewhere to live, somewhere to get food from. At the same time, in the film, she’s a religious woman — she wants the best for her daughters and fears to see them losing their way. She becomes a moral compass and stands in for the audience as the girls both get lost in the court.”

“It’s strange to describe the time, because the words we have are all modern. On the other hand, human beings haven’t changed that much,” she continues. “Obviously, behavior has changed, but feelings, emotions haven’t changed at all.”

David Morrissey plays the Duke of Norfolk, uncle to Anne and Mary Boleyn. A man who would be the power behind the throne, the Duke plots to raise his family’s profile in the court by any means necessary.

Morrissey notes, “Not only does he put both Mary and Anne in the king’s path, but — and the film doesn’t deal with this — the Duke of Norfolk was also the uncle of Katharine Howard, Henry’s fifth wife. He was an operator, ambitious, ruthless, shrewd, and quite unscrupulous, at least as far as his nieces were concerned. Although now it’s outrageous for us to think of somebody who would treat his relatives this way, at the time, women were a currency.”

Jim Sturgess, who plays George Boleyn, describes his character as “a loveable rogue, with an energetic, wide-eyed love for the court and everything it has to offer. He immerses and indulges himself, but he’s also as ambitious as his father and his uncle. He understands that he has a role to play in this strategic game, even if he’s just a pawn.”

In addition to the chance to work with Portman and Johansson, Sturgess was intrigued by the film Chadwick intended to make. “He really wanted to get to the grit and reality of what life was like in the court — showing the filth and madness that went on behind the gates,” he says.

“George and Anne and Mary are definitely a group, those three,” Sturgess says. “George is very much the mediator between the two girls. He has a very loving relationship with both of his sisters. I think he would side with Anne slightly more as she’s the more mischievous of the two girls, but he loves both of his sisters dearly. In fact, his love and his loyalty for Anne is, in a way, what kills him in the end.”

About the Shooting

The Other Boleyn Girl was shot in high definition. Says Justin Chadwick, “We shot `Bleak House’ on HD and really appreciated the different quality it gave to the final look of the film, so I was pleased that Sony was interested in us working on HD again. The huge advantage is that nothing is hidden — you can see every detail. In a close-up you feel you can reach in and touch the actor; you can see into the actor’s eyes. It’s not the obvious thing for a period movie, but I wanted to capture performances, not do wide shots of the beautiful locations we were using. The film will have its own unique look.”

“Shooting in HD gave us a lot of options,” says Kristin Scott Thomas. “We could do a lot of takes. Justin was a very generous, very sensitive director, and he gave us the opportunity to make a very passionate film.”

Chadwick was determined to shoot as much as possible of The Other Boleyn Girl on location. “If the characters are at home in their real surroundings, it adds to the performances,” he explains. In the end, the majority of the film’s exterior shots were filmed in real castles and estates throughout England, but for some interior shots, the realistically weathered look that Chadwick envisioned required building sets in the studio. “We did visit lots of the real locations, such as Hever Castle where the Boleyn family lived for a time, but most of those places are now part of the tourist heritage industry and have been cleaned up for visitors. They just don’t have the atmosphere they would have had during Henry’s reign.”

For John-Paul Kelly, the production designer, the initial approach to determining the design of the film was to do research on the Tudor period and to visit potential locations. “At first, I went on the road with Justin and Kieran McGuigan, the director of photography. We drove around possible locations and talked about how the film might look. Justin wanted the look to be relevant, modern, and alive. The Tudor period was incredibly energetic, a time of massive change in the world, and Henry’s court was the beginning of the modern Britain we live in now. We wanted to keep the backgrounds alive and vibrant and interesting. Our starting point was to balance period accuracy with creating a modern and exciting story.”

To create this unique mood, Kelly searched through old photographs from around the world for inspiration. He found ideas for his representation of the Tudor court in such diverse pictures as street scenes from India and nightclubs from Berlin. Kelly says that while it was important to the filmmakers not to have anachronistic elements in the film, at the same time, they looked for the film to “give you the essence of the period without bogging you down in details. I wanted to reflect the flavor and the excitement of the images that excited us.”

Two of the critical settings in the film are the Boleyn family home and Whitehall Palace, the home of Henry’s court. To shoot the Whitehall ball sequence, Kelly and his team built large areas of Whitehall Palace across two stages in the George Lucas Building at London’s Elstree Studios. The scene is key, according to Kelly, because this is when “the Boleyn sisters experience the full exhilaration of Henry’s court for the first time. And of course they both react in different ways; Anne totally buys into that world, and Mary would rather not be there.”

Kelly’s set highlights the moment. “We wanted a massively long corridor, which gives the scale of the Palace. We wanted the ball to feel more like a party, where you can ramble between rooms, with action in various corners, rather than look like one of those big set piece balls you often see on film. It looks nothing like a Berlin nightclub, but hopefully has that sense of excitement.”

Kelly’s favorite set was Henry’s bedroom, also built on stage. He says, “I thought it would be interesting for Henry to bring Mary into a forest-walled room, so I decided to paint a mural all the way around, using colors which might have been used on a tapestry. Also, because there is very little furniture remaining from the period, we designed and made much of it. It was a fantastic moment of excess for me, to design and make a bed for King Henry VIII.”

Whitehall Palace was burned down and then rebuilt, so there was little reference available for the original 1530s palace. “In reality, the palace probably had lots of long dull corridors, with bits of brown furniture. The challenge on a period film is to find a kind of reality that is true to history, but allows you to tell your story in the way you want to,” says Kelly.

Both Kelly and costume designer Sandy Powell relied on the color palette used by portrait painter Hans Holbein. “When Holbein painted Henry’s court, he worked in a completely different way from his contemporaries,” Kelly says. “His palette was very particular, including a lot of turquoises, strong blues, and deep greens. We’ve based our color schemes on that palette and coordinated with each other, so that the furnishings and the clothes are complimentary. They tell the same story.”

About the Costume Design

For Costume Designer Sandy Powell, who has been nominated for a total of seven Academy Awards, winning Oscars® for her work on Shakespeare in Love and The Aviator, the chance to work on The Other Boleyn Girl represented a great challenge: Powell and her team were responsible for designing and making hundreds of original costumes true to the Tudor era.

Like her colleague, production designer John-Paul Kelly, Powell turned to the paintings of Hans Holbein for inspiration for the costumes of Henry and the Boleyns. “He was the only artist of the time painting the Court of King Henry, and in such detail. The accepted image of Henry today is from Holbein’s painting that hangs in the National Gallery, with the king standing hands on hips, his legs astride. Of course, in our film, we are depicting Henry at a younger age, so we have our own Henry.”

According to Powell, capturing the authentic look of the period while maintaining high levels of creativity and originality is a balancing act for any designer working in a specific period. “You always have to use artistic license; you can never be strictly authentic, and besides, no one knows what authentic is, anyway,” she says. “We don’t have complete information about the clothes, and we don’t have the same fabrics. I do my research and then do my own version. I do what is right for the character, or the actor, or the scene, or the film as a whole. We have a story to tell.”

One of the keys to the film is differentiating between Mary and Anne Boleyn. Powell explains, “There is not a great deal of variety in the shape or silhouette of a Tudor dress, and the girls shared the same life and moved mainly in the same circles, at home or at Court, so I used a difference in tone and shade to separate them. Mary’s character is slightly softer and more romantic than Anne, who is seen as stronger and more forceful. So, without being as obvious as one girl in red and one in blue, I’ve dressed them in different hues.”

Powell also used the costumes to subtly reflect the politics of the time. “For example, with the girls’ father, Sir Thomas Boleyn, I’ve made each outfit a little bit grander than the last one, and finally a little bit vulgar towards the end. His power at Court is increasing, and with it, his wealth. Like a nouveau riche person today, he’s got money and he wants to show it.”

The designer does have one favorite costume: “Natalie wears the Lily Dress while riding a horse,” she says. “It’s bright green, with embroidered lilies up the front.”

“Costumes are always very helpful,” says Johansson, noting that it’s especially true in a period piece. “The way you hold yourself, how grand you feel when you wear it. For Mary, her character changes as her costumes change. In the country, she has simple cotton dresses that are easier to work with. Later in the film, she becomes very motherly — a child on her hip — and in the huge court dresses, it’s impossible. You feel the change of character.”

About the Locations

The house and grounds of Great Chalfield Manor, near Bath, was used by production as the country home of the Boleyns. The manor served as the location for two key scenes: Mary’s wedding to William Carey and the king’s visit to go hunting with Anne and George. The manor house and the tiny parish Church of All Saints within the grounds were rebuilt in the 15th century and the house has been continuously occupied since then, for the past 130 years by one family. The Fuller family restored the property in 1905 and donated the house and the grounds to the National Trust in 1943. The manor is a splendidly preserved example of the architecture of its time — an amalgamation of medieval features, including a gabled entrance porch, oriel windows, and a central Great Hall, with the “modern” (16th Century!) addition of a parlor.

Nearby, the production used Lacock Abbey as the gardens, cloisters and rooms of Whitehall Palace, where Queen Katherine first confronts the Boleyn sisters and Anne plays with young Henry to remind the king of his desire for a son and heir. Lacock Abbey was founded in the 13th century by the Countess of Salisbury; at any time, it would house 15 to 25 nuns. The local village poor benefited from the Abbey, as the nuns distributed food and money to the needy. Most of the villagers who farmed the land were tenants of the Abbey, and paid their rents in grain, hides, and fleeces. Following King Henry’s split from the Church, Lacock Abbey, like many other religious houses, was sold to a wealthy landowner; it has remained in the same family since the 16th Century.

Saint Bartholomew’s Church in the Smithfield area of London was the scene of both the trial of Queen Katherine and the grim wedding of pregnant Anne Boleyn and King Henry. Adjacent to Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital and Smithfield Market in an area increasingly popular for its bars and restaurants, Saint Bartholomew’s is an active Anglican/Episcopalian Church, built in 1123 when Henry I, son of William the Conqueror, was king of England. It survived the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the bombs dropped during both World Wars.

The executions of Anne and George Boleyn, which took place within the Tower of London, were filmed in Dover Castle. Built high on the cliffs of the southeast coast of England, overlooking the shortest sea crossing between France and England, there has been a fortress in this strategic location since Roman Times. King Henry VIII appreciated the strength of this bastion when a Catholic invasion of England seemed inevitable, following the annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon and the dissolution of a peace treaty between Spain and France. Henry ordered the strengthening of the country’s defenses, commissioning a chain of coastal artillery forts. He visited Dover Castle to check on the progress of the work in 1539.

Knole House, a stately home in Kent in southeastern England, is known as a calendar house because of its 365 rooms. The house was owned by Henry VIII after he took it from the Archbishop of Canterbury; he used it as a hunting lodge. Henry’s daughter, Queen Elizabeth, gave the house and the 1000 acres of deer park surrounding it to her cousin Thomas Sackville, whose descendents, the Dukes and Earls of Dorset and the Barons of Sackville, have lived there ever since. Portrayed in the film as the exterior of Whitehall Palace, the house rooftops are also featured as the spires of London by night, as Mary Boleyn flees from court to return to William Stafford in the country.

Mary’s journey on horseback takes her through the Derbyshire Peak District, showing the spectacular countryside around Dovedale and beneath Stannage Edge. As she arrives at the home she shares with William Stafford and her children, we see the exterior of North Lees Hall, which is reputed to have inspired Charlotte Brontë’s description of Thornfield Hall, the home of Mr. Rochester in her novel Jane Eyre.

Rooms within Haddon Hall, also in the Peak District, were used as other interiors of the Boleyn home. Haddon Hall is one of England’s finest medieval and Tudor houses, having been described as “the most perfect house to survive from the Middle Ages.” It has belonged to the Manners family since 1567 and, after lying empty for 200 years, was restored by the Duke and Duchess of Rutland in the 1920s.

Penshurst Place, also in Kent, features in the film as the gardens and the grand dining hall of Whitehall Palace. The manor house is the most complete example of 14th Century domestic architecture that survives today. Henry’s son, Edward VI, granted the estate to Sir William Sidney in 1552, and the family has been in occupation ever since. The previous owners were the Dukes of Buckingham, one of whom entertained Henry VIII in the Baron’s Hall in 1519. Two years later, his royal hospitality forgotten, the Duke was beheaded for treason. In fact, three successive Dukes of Buckingham lost their heads during the Tudor monarchies.

About King Henry VIII

Henry Tudor was born in 1491, the second son of King Henry VII of England. His older brother Arthur died, leaving Henry to inherit his father’s throne. He first married Katherine of Aragon, his brother’s widow, a match only permitted under Roman Catholic law of the time because of the claim that Katherine and Arthur’s marriage had never been consummated. With Katherine, Henry had one daughter, Mary. Henry divorced Katherine after falling in love with Anne Boleyn. His need for a male heir played a large part in his desire to marry the pregnant Anne, but Anne gave Henry another daughter, Elizabeth. The marriage lasted only three years before Anne was beheaded for infidelity, a treasonous charge in the king’s consort. Henry hastily married Jane Seymour, who died in childbirth, giving Henry the son and heir he longed for, Prince Edward.

Henry next arranged a marriage with Anne of Cleves, reportedly attracted to her after seeing Hans Holbein’s beautiful portrait of her. But in person, he found her plain, and the marriage was never consummated. Catherine Howard, another niece of the scheming Duke of Norfolk, was Henry’s next wife but she was executed for infidelity within two years. His sixth and final wife was Catherine Parr, who outlived him. Henry died in 1547, at the age of 56.

Henry was succeeded first by his nine-year-old son, Edward VI, whose reign lasted for six years. When he died, he was succeeded by Lady Jane Grey, who was not in line for the throne and was forced to give up the crown after just nine days when Katherine of Aragon’s daughter, Mary, rode triumphantly into London. Mary became known as Bloody Mary because of her intolerant attitude to non-Catholics. Upon Mary’s death, Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth, was crowned Queen of England; she began a long and celebrated reign that came to be called a golden age.

As a young and vigorous king, Henry invaded France, defeated the Scots at Flodden Field and wrote a treatise against the reformation of the Church, for which the Pope rewarded him with the title “Defender of the Faith.” However, his obsession with having a male heir to inherit the throne of England led to his divorce from Katherine, which was condemned by the Pope, who had refused to annul the union. Henry broke from Rome, separating the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church, and asserting the supremacy of the Monarchy, an event that greatly altered the politics of England and the whole of Western Christendom, fracturing the absolute power of the Church of Rome.

Production notes provided by Columbia Pictures.

The Other Boleyn Girl

Starring: Natalie Portman, Scarlett Johansson, Eric Bana, Kristin Scott Thomas, Mark Rylance, David Morrissey

Directed by: Justin Chadwick

Screenplay by: Peter Morgan

Release Date: February 29, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for mature thematic elements, sexual content, violent images.

Studio: Columbia Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $26,814,957 (37.0%)

Foreign:$45,721,198 (63.0%)

Total: $72,536,155 (Worldwide)