This fall, our vision of the world will change forever.

An outbreak of blindness sweeps an unidentified town. Ruffalo will play a doctor who loses his sight along with everyone else in town, except the doc’s wife. When a sudden plague of blindness devastates a city, a small group of the afflicted band together to triumphantly overcome the horrific conditions of their imposed quarantine.

It begins in a flash, as one man is instantaneously struck blind while driving home from work, his whole world suddenly turned to an eerie, milky haze. One by one, each person he encounters – his wife, his doctor, even the seemingly good Samaritan who gives him a lift home – will in due course suffer the same unsettling fate. As the contagion spreads, and panic and paranoia set in across the city, the newly blind victims of the “White Sickness” are rounded up and quarantined within a crumbling, abandoned mental asylum, where all semblance of ordinary life begins to break down.

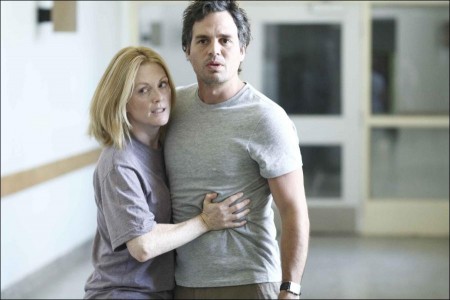

But inside the quarantined hospital, there is one secret eyewitness: one woman (Julianne Moore) who has not been affected but has pretended she is blind in order to stay beside her beloved husband (Mark Ruffalo). Armed with increasing courage and the will to survive, she will lead a makeshift family of seven people on a journey, through horror and love, depravity and beauty, warfare and wonder, to break out of the hospital and into the devastated city where they may be the only hope left. Their journey shines a light on both the dangerous fragility of society and the exhilarating spirit of humanity.

About The Production

“I don’t think we did go blind. I think we always were blind. Blind but seeing. People who can see, but do not see.” — José Saramago, Blindness

In 1995, the acclaimed author José Saramago published the novel Blindness, an apocalyptic fable about a plague of blindness ravaging first one man, then a city, then the entire globe, with devastating fury and speed. Though the story was about a stunning loss of vision, the book opened the eyes of its readers to a new and revealing view of the world.

The book was celebrated by critics as a classic-in-the-making, a magnificent parable about our disaster-prone times and our metaphoric blindness to our sustaining connections to one another. It became an international bestseller, and also led, along with an accomplished body of equally thought-provoking literature, to Saramago garnering the 1998 Nobel Prize for Literature.

As the novel rapidly gained millions of fans around the world, many filmmakers were magnetically drawn to its intricately created world, one that had never been seen on screen before. After all, how does one make a compellingly visual film in which almost no one can see? It called for a grand vision and one filmmaker who had such a vision right from the start was Fernando Meirelles, who, at the time, was an up-and-coming Brazilian filmmaker with a passion for big, intense, all enveloping cinema.

But at the time, Saramago rejected all his suitors, saying he was uninterested in a movie version of Blindness – and Meirelles went on to make another heartfelt movie, his groundbreaking, electrifying, yet lyrical tale of life among the young, fearless gangsters in Brazil’s slums, “City of God.”

Meanwhile, multitalented Canadian screenwriter, actor and director Don McKellar was also trying to win the rights to Blindness. McKellar, whose films include the end-of-the-world drama “Last Night,” was grabbed by Saramago’s themes as soon as he read the English translation of Blindness, and he knew they weren’t going to let him go until he wrote his vision of the adaptation. He approached producer Niv Fichman of Rhombus Media – with whom he had collaborated on both “Last Night” and as a screenwriter on the Oscar®-winning “The Red Violin” — with the idea of securing the rights. As soon as Fichman read the book, he was equally fervent about it but there remained that one major obstacle in their way: convincing Saramago.

“I always resisted (giving up rights to the Blindness),” Saramago told the New York Times Magazine in 2007, “because it’s a violent book about social degradation… and I didn’t want it to fall into the wrong hands.”

But Fichman and McKellar were not going to give up. All they wanted was a chance to meet with Saramago and present their case and, after months of persistent calling, convincing and cajoling, they finally received word that Saramago would meet with them . . . so long as they were willing to travel to his far-away residence in Lanzarote, one of the Canary Islands. Fichman’s immediate response was, “Excellent. Yes. Where’s Lanzarote?”

On the way to visit the octogenarian author, they developed their strategy. They would not discuss the book or their vision for the film, but rather try to impress upon Saramago the creative freedom their team, based in Canada, would bring to the picture. “I think Saramago was afraid that a studio would turn this into a zombie film and lose the fundamental underlying politic of the story,” says Fichman. “So we explained that control would remain in the hands of the filmmakers – and that we wouldn’t have to send our rushes to anyone. We explained that we would have the freedom to cast who we want, to shoot how we want, and do whatever we felt was right for the film.”

The strategy paid off. “I think Saramago was impressed by our commitment,” recalls McKellar, “I think he trusted that we had the integrity he was looking for and that we wouldn’t compromise the film.”

At last, Saramago agreed and McKellar began tackling one of the most exhilarating challenges of his career. “I knew that that the tone of Saramago’s book would be very hard to achieve on film,” explains McKellar, “None of the characters even have names or a history, which is very untraditional for a Hollywood story. The film, like the novel, directly addresses sight and point of view and asks you to see things from a different perspective. For me, as a screenwriter, I saw that as very liberating.”

McKellar also understood that the film would have to diverge from the book in several key ways. Most importantly, he had to consider the idea that in a movie theatre, the audience was going to develop an unusually voyeuristic relationship with these characters who can be seen but can’t see back. In the book, only the Doctor’s Wife can see all the harrowing events that take place, but in the film, the audience would join her in bearing witness. The burden of sight would be shared between them, and that was a delicate situation that McKellar had to carefully navigate.

“Like the Doctor’s Wife, the audience is watching people and that calls into question the humanity of observing and not acting, which becomes a major theme of the film,” notes McKellar. “In some scenes, especially the rape scene, you are seeing things you don’t necessarily want to see. You want the freedom to look away, to turn your head, but it’s not being allowed. I wanted the audience to be sharing in the perspective of the Doctor’s Wife as her field of responsibility widens.”

The Doctor’s Wife helped to lead McKellar deeper into the story. He continues: “I even asked Saramago why the Doctor’s Wife took so long to take action in the hospital? Why didn’t she act faster? Why, when she saw what was happening, didn’t she grab her scissors and kill? He said she became aware of the responsibility that comes with seeing gradually, first to herself, then to her husband, then to her small family, then her ward, and finally to the world where she has to create a new civilization. It was a responsibility that she didn’t know was in her. She becomes aware of it through actions and circumstances, and that is something I wanted to be strongly felt in the film.”

Ultimately the power of the script entranced all who read it and also brought on board two additional producers: Andrea Barata Ribeiro of O2 Filmes, which had produced “City of God” and the recent sequel “City of Men” and Sonoko Sakai, founder of LA/Japan-based Bee Vine Pictures, who recently served as a producer on Francois Girard’s adaptation of “Silk.”

Flying Blind

Once Niv Fichman read Don McKellar’s suspenseful, illuminating and, stunningly visual screenplay for BLINDNESS, he knew they would need a director with a matching sense of pace, scale and creativity, as well as an intense interest in the spectrum of human nature. This led them full circle back to Fernando Meirelles, who in the intervening years, had become an internationally acclaimed director.

He had broken ground for an exciting new era of global cinema with “City of God,” his intoxicating and inventive journey into Brazil’s crime-ridden underground, which was filled with visual panache and action yet also scenes of unforgettable poignancy. The film was nominated for four Academy Awards, including a nomination for Meirelles as Best Director. Meirelles then moved on to Hollywood to direct the heart-pounding screen adaptation of John Le Carré’s Africa-set political thriller “The Constant Gardener,” starring Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz, which received another four Oscar nominations.

His ability to invite audiences into new and perspective-changing worlds with his ambitious sense of style was a major deciding factor. “When I would dream about what would be perfect for BLINDNESS, I’d dream of the kinetic energy and naturalistic performances in `City of God,’ combined with the elegance and very subtle politics of `The Constant Gardener,’ so I knew that Meirelles was the right choice,” says Fichman. “We had started with a book from a Nobel Laureate, we had an adaptation from one of the great screenwriters of the world, and now with one of the most innovative directors, we had created a package that gave us incredible strength.”

“Five minutes of talking was all it took to convince Meirelles to take the helm of BLINDNESS,” recalls producer Andrea Barata Ribeiro, “Fernando could have made any type of film, but he and everyone who has worked closely with him knows of his concern with making the world a better place and this story was always important to him.”

Meirelles began with his eyes closed – literally. He spent hours with them tightly sealed, thinking about how the world would feel and sound, what it would really be like from the inside, if you suddenly lost your vision. For further inspiration, he read the book over and over, six or seven times, letting Saramago’s multilayered portrait of humanity under siege wash over him.

He understood the story could be interpreted in any number of ways – as a metaphor about the personal and political reactions to recent natural disasters; as an allegory about the perils of the future; as a commentary on choosing not to see what is happening around you; as a meditation on primal instincts; as a probe into the human conscience in all its desperate weaknesses and astonishing strengths – and he wanted the movie to be all these things and yet none of them explicitly.

“This story does not have one truth, and all the different interpretations make sense,” he says. “There are many moral dilemmas and I think the film goes even further in this direction than the book, where things are a bit more black and white. I have added a lot of grey. This is a story that must create a lot of questions, but give no answers. It raises issues about man’s evolution, makes us reflect critically, but points in no specific direction. As in the story, each one will have to discover their own road by themselves.”

But when it came to the film’s visual style, Meirelles eschewed the grey. He wanted to emphasize the unexpected kind of blindness specified by Saramago, not a lights-out darkness but an impermeable, radiant fog that obscures, but does not blot out, the world. “My first instinct was to take this dark story and make a very bright film, with an almost oppressive brightness,” he comments. Thus, even as all sight, civility and societal structure falls away for the characters, the film maintains a glaring luminosity that suggest a light on just the other side of the darkness.

Meirelles is renown for making visually arresting, high-energy films out of challenging subjects and in challenging places, but with BLINDNESS he faced perhaps the biggest challenge of them all: how do you shoot a story in which none of the characters, save one, has a point-of-view? To address this, Mereilles took the risk of switching points-of-view throughout the film. He begins the film with a director’s omniscient vantage point, but then, inside the hospital-tuned-gulag he shifts to the interior POV of the Doctor’s Wife, because she is the only one can see. Once the audience has settled into that world, the POV changes again, this time to the Man with the Black Eye Patch who connects those being quarantined to stories from the outside world and to their own inner worlds.

The result is a kind of building multiplicity of voices and perspectives -one that echoes Saramago’s prose style and hints at a different way of seeing. To enhance this further, Meirelles divided the story into what he sees as three distinct stylistic sections. “The first act is when everybody is going blind, and that all moves very fast and is almost like an action film,” he observes. “I felt it was important for the audience to experience the oppression of not knowing what is going on at the beginning.”

Then, once again, everything changes. “For the second act when the doctor and his wife come to the asylum and experience the blindness,” he continues, “we used a lot of abstract images to convey the feeling of really being lost. This act also introduces the Man with the Black Eye Patch as and the Bartender who declares himself the King of Ward Three, and the story goes in a different direction with one group fighting against the other group in a kind of gang warfare. Then, after the fire in the asylum, a new door opens, people leave and it becomes a new film again.”

Though his vision was complex, once on the set Meirelles became known for his wide-open sensibilities, allowing for improvisation and creative accidents. Meirelles also added to the already global flavor of the production. “Fernando has a way of putting everybody at ease. There are no boundaries. On set we’d hear Portuguese, English, French, Spanish, and Japanese and yet we all spoke one language – the language of making a beautiful story,” summarizes producer Sonoko Sakai.

The Doctor and His Wife

At the heart of BLINDNESS are the Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife, two ordinary people plucked from their ordinary lives into a maelstrom of disorientation and confusion. The Doctor’s Wife, the only person in the story who, through luck of the draw, is immune to the infection and can still see (despite pretending she is blind), becomes the audience’s eyes in a sense and their conduit to everything that is happening to those whose vision is a blank. She guides the audience into the terrifying and threatening world of the abandoned sanitarium, where anyone can be killed at any time – whether by the frightened guards or the frantic inmates themselves. Surprising herself, with her back pressed to the wall, she becomes a true leader among her blinded fellow human beings, spurring them on to learn to live in the midst of their anguish and uncertainty.

To play the Doctor’s Wife, the filmmakers recruited four-time Academy Award® nominee Julianne Moore, who is known for her subtly nuanced and deeply emotional performances in such films as “Far From Heaven,” “The Hours,” “The End of the Affair” and most recently Alfonso Cuaron’s vision of a dystopian future, “Children of Men.” Moore felt an instant link to the character, who she views not necessarily as a heroine but rather as someone driven, like all of us, to survive, a drive that takes her to dark places but also to a strength inside her she had not understood was there.

“The Doctor’s Wife is just a normal human being and I think that’s one of the great things about the novel. She is fallible, and a lot of what she does initially just skims the surface of what she really could be doing, keeping things clean, tying up wires. Her biggest concern in the beginning is simply her husband. But her ability to see ultimately both isolates her and makes her into a leader,” comments Moore. “I think with this character, Saramago poses the idea of responsibility. He asks who are we and how responsible are we for one another, for the world we live in and for what we do in it? You have to consider how aware you are of the consequences of your actions, which really comes into play with the Doctor’s Wife.”

Moore had long been yearning to work with Meirelles when she received the script for BLINDNESS. “When I heard he was making this movie, I really wanted to do it. He’s a brilliant director with an astonishing point of view,” she says. “Then, after reading the script, I also felt that BLINDNESS was massive and important and a story we need right now.”

The actress delivered a shock to the filmmakers when she arrived on set as a blonde. Meirelles had asked Moore to cut her hair for the film, but she took the transformation a step further, an idea that occurred to her while reading the screenplay. “I just had an instinct that it was right for the character,” she explains. “Red hair makes you stand out because you are in the minority. I wanted the Wife to be a majority figure.”

On the set, Meirelles was astounded by Moore’s combination of skill and emotional tenderness. “Technically, she’s like a machine; you say something and she responds immediately, she perfectly understands the story, the moment, the plot, and she knows precisely how close to be to the camera. At the same time, she is pure cinema. She has something, and I’m not even sure what you call it… Charisma? Expressiveness? Whatever it is, every day I was overwhelmed by her performance.”

Contrasting with the Wife’s upward swing of gaining courage is the tumbling descent of her husband, the Doctor. He begins the story as a strong, responsible community leader but, once blinded and interred in the hospital, he must grapple with a growing sense of powerlessness and despair that leads to subjugation. To play the Doctor, the filmmakers chose Mark Ruffalo, whose career took off with his charmingly vulnerable role in the hit indie “You Can Count on Me” and has gone on to give memorable performances in a string of films that include “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” “Collateral,” “All The King’s Men,” “Zodiac” and most recently, “Reservation Road” with Joaquin Phoenix. Ruffalo was a perfect match for this pillar of the community who plunges into a nightmare beyond his imagining.

As soon as he read the screenplay, Ruffalo could not resist wanting to explore the Doctor’s intense experience in the strange land of the newly blind. “What I found interesting is that the Doctor comes to find out that he is not who he thought he was and then, in one heartbreaking moment, he also finds out that his wife is not who he thought she was. The interesting truth of the matter is his wife is who he had hoped he would be under these circumstances. And he is the type of person he assumed his wife was. And that’s a very difficult moment for anybody, to have all their perceptions completely shattered,” he says. “But I think the Doctor finally comes to a peace about his inabilities and his downfall, and admits to an admiration for his wife’s strengths.”

Ruffalo had first met with Meirelles in Cannes in 2007 to discuss playing the Doctor, but then it looked like the production would overlap with the expected due date of Ruffalo’s third child. Despite how much he wanted the role, Ruffalo made it clear he needed to be with his wife for the birth. Meirelles however, was convinced that Ruffalo was right for the role, and as a result BLINDNESS’s wrap date was moved up to free Ruffalo in time – and fortunately, the baby cooperated.

Summarizes Meirelles of Ruffalo: “Mark has this quality of raw honesty, not only in his characters, but personally. He brings great warmth to the Doctor and I think his performance is brilliant.”

The Man with the Black Eye Patch: Danny Glover

If the Doctor’s Wife becomes the eyes of BLINDNESS, the character known as the Man with the Black Eye Patch provides access to the story’s soul. An inveterate storyteller who also serves as the movie’s narrator mid-way through, Fernando Meirelles always saw the Man with the Black Eye Patch as the on-screen manifestation of author José Saramago. “For me, it was like having the novelist as part of the cast,” notes Meirelles.

A patient of the Doctor and a man who was already blind in one eye when the “White Sickness” struck, the Man with the Black Eye Patch is in a unique position to navigate the world of the blind, having been half-way there already. He comes to the fore when he brings news – or is it rumors? – of what happened in the outside world in the days after the first blind people were interred, spinning stories of overturned busses, planes crashing into one another and government dissolution. But as the film goes on, he becomes its inner voice, his observations, ultimately floating, disembodied above the proceedings.

The Man with the Black Eye Patch would require an actor of maturity, soulfulness and grace, which ultimately led to Danny Glover, the veteran star who has played an astonishingly broad diversity of roles from the comic action of the “Lethal Weapon” series opposite Mel Gibson to playing Nelson Mandela in the telefilm “Mandela”; from playing Paul Garner in Jonathan Demme’s screen adaptation of Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and Albert in Steven Spielberg’s screen adaptation of “The Color Purple” to his recent turn in the hit musical “Dreamgirls.”

“The Man With The Black Eye Patch comes into this new world of blindness already half blind, so I think he understands where he is within his own truth, within himself. I did feel like this character was very much like Saramago because he is completely unapologetic — he is who he is and he accepts who he is,” explains Glover.

Most of all, Glover was taken in by the depths of BLINDNESS and all the swirling thoughts it provoked. “Our human aesthetic is based on our ability to see,” he observes. “And I think Saramago is saying that when we take that away, the kind of relationships we form and the journey to forming those relationships must be transcendent and sustainable. How people come out of this experience is the key, and I think it all relates to the idea that if we march into the 21st and 22nd centuries without a new ethos, we will be lost.”

The Woman with Dark Glasses: Alice Braga

One of the most mysterious characters in BLINDESS is the Woman With Dark Glasses, played by Alice Braga, who first worked with Fernando Meirelles playing Angelica in “City of God” and who recently starred in another apocalyptic tale, “I Am Legend” opposite Will Smith. Meirelles always had her in mind for the role. “Alice is a very good actress and a very good friend, and I knew I wanted a Brazilian actor in BLINDNESS,” he says. “At first, I had some concerns about having her act in English — a language she learned only 3 to 4 years ago — but I took the risk and it paid off. I think she has the kind of charisma that is something you are either born with or not.”

Braga approached her character as someone who starts off quite secretive and enigmatic but becomes a richer and more open human being, especially as she grows closest to the orphaned Boy with the Squint, who needs her help to survive the dangers of the quarantined “camp.” “The Woman With The Dark Glasses is mysterious,” says Braga. “While she does sleep with men because it is easy money, I did not want to treat her purely as a prostitute. She starts out quite tough, but then she develops very strong maternal feelings.”

Meirelles was impressed with how Braga pulled off the character’s evolution. “When she first arrives at the hospital, covered by her glasses and her cascading hair, you don’t really know who she is or understand her relationship with the Boy. She seems so cold, without warmth or affection. But then she begins to see with different eyes, from inside. Scene by scene, she becomes warmer, like a real human being. That’s Alice’s arc. Because of her blindness, the Woman with Dark Glasses learns to see.”

The Thief and the King of Ward Three

To play the man known as the Thief, who begins BLINDNESS as the Good Samaritan who gives the First Blind Man a ride home, the filmmakers turned to an unusual source: the film’s screenwriter, Don McKellar, who also is an accomplished actor. “I didn’t write the part of the Thief for myself,” McKellar explains, “but I was always very interested in him. You first see the Thief as the good samaritan who gives the First Blind Man a ride home but later proves to take advantage of the situation when he steals his car. I like the trick that you think the Thief is the bad guy. He’s a pathetic character you first believe is the villain of the piece and then you realize that, no he’s not even close to that. There’s something charming about his desperation because after a point, you meet the King of Ward Three and learn what real desperation is.”

The King of Ward Three starts out known as the Bartender, his occupation in life before the “White Blindness” sets in. But inside the quarantined hospital, the Bartender appoints himself the royal dictator of Ward Three and then the rest of hospital, as he begins to control all of the meager resources provided by the government – namely food – by demanding jewelry, goods and ultimately women in trade.

The role went to one of today’s most electrifying screen stars, Gael García Bernal, who came to the fore in Alejandro Gonzalez Innaritu’s breakout films “Y tu mamá también” and “Amores Perros” and garnered acclaim and awards for his performance as a young Che Guevara in Walter Salles’ “The Motorcycle Diaries.”

Bernal had long been a fan of the novel. “I always thought it was a transcendent story,” he says. “It is about the inability of people to live together, about what happens when people don’t really see each other. I like that it creates a situation that puts to the test all the social and moral structures we have been taught. The wards become chaotic and corrupt like the world. But in the end, it’s a hopeful story because the only thing that can save us is ourselves.”

Bernal knew he would be taking on an extremely demanding part, a portrait of power’s corruptions yet one that had to maintain its own sense of humanity, that had to be at once comical, savage and true. “I think the King is just very practical, very pragmatic. He appears cold because he is not an idealist and he does not see hope, but he is a survivor, the same as all the others,” observes Bernal. “To say the King is evil would be to go against the point of the story. He chooses practical solutions for the benefit of his ward. And what is so powerful about him is that his actions result in a very heated debate about morals.”

The first man to go blind in BLINDNESS, Patient Zero as it were, becomes the arrow that drives the story forward. The audience follows in suspense as he suddenly loses his vision while waiting at a red light, flails through the now hostile world and as he tries to come to grips with what is happening to him and why. Accepting a ride home from a stranger (later to become the Thief), he soon passes the strange infection to his angry, disconsolate wife and starts off a chain reaction that will quickly grow out of control.

The First Blind Man and his Wife are perhaps the characters who changed the most in Don McKellar’s adaptation of Saramago’s novel. For one thing, McKellar added in a note of marital discord that gives the opening scenes an even greater emotional tension, and becomes another theme unto itself – for the blindness breaks open an invisible rift between the couple, who find themselves uncertain at first of what connects them at all without sight.

Secondly, although the ethnicity of the characters doesn’t enter into the novel, McKellar and Fernando Meirelles made the decision early on to cast two actors of Asian background to add to the film’s mix of cultures, typical of any postmodern mega-city. But having made the decision, they then spent months searching for the right actors. Ultimately, they chose Japanese heartthrobs Yusuke Iseya and Yoshino Kimura, who both starred in the 2007 Japanese hit, “Sukiyaki Western: Django,” a remake of Sergio Corbucci’s 1966 Spaghetti Western, also starring Quentin Tarantino, from maverick director, Takashi Miike.

Both spoke just enough English to make the roles work and most importantly, they had an essential chemistry that allowed them to work beautifully together in silence. “Fernando made the brilliant realization that even though the parts were written in English, the couple could be speaking Japanese amongst themselves, so they didn’t have to be fluent in English,” says Sonoko Sakai. “This allowed us to look for great actors which we found with Iseya and Kimura.”

Once the cast of BLINDNESS was chosen, an enormous task lay at hand: to submerge them all in the experience of being suddenly, inexplicably and irrevocably blind. To do this, the filmmakers brought on board acting coaches turned “blindness coaches,” Christian Duurvoort and Barbara Willis Sweete, who, after doing extensive interviews with blind people, developed their own creative system for teaching the sighted to physically maneuver as if they cannot see.

They began working with the actors in a series of intense “blindness workshops,” that explored space, experimented with smell and sound, and simulated such physical tasks as finding food, setting a fire and assaulting someone while blind. Each actor began with a total immersion, spending hours blindfolded, simply to become accustomed to what it felt like to have no use of their eyes. Eventually, blindfolds were removed, graduating to moving with eyes shut and then performing with eyes open. Key actors also had the option of wearing lenses that effectively blinded them, something they’d often opt for during intense scenes that allowed them to focus on acting rather than on not seeing. “At first I asked for the lenses,” explains Alice Braga, “because there were too many things to think about: not looking and being in the moment, feeling the emotions, and speaking in a different language. But after twenty days of filming, I stopped using them because I had become so connected to feeling the part.”

Over time, the main cast as well as several hundred extras, who also had to be completely authentic in their blindness, began to adapt to working without sight. “It takes time to teach not only blindness but more importantly `recent blindness,’” notes Duurvoort. “But with that time, you start to realize certain things. For the blind, space is what your body touches. Also, sighted people hear sounds that they do not pay attention to, but for the blind, all kinds of noises become very important.”

So impressed by these workshops was Meirelles that not only did he participate, but he also urged everyone, including cinematographer César Charlone and other key department heads, to sign up, which would come to influence the very look and design of the film. “For me,” Meirelles said, “the biggest revelation was sound – how you hear things, how sound changes for you, how it changes your perceptions of the world around you. So in this film you will hear much more. We use very clean sound, so the audience will pay attention to every little noise.”

Everyone who participated had their own deeply personal experiences in the blindness workshops. “You come to a situation like this with some anxiety,” says Danny Glover. “But Christian gave me a sensibility about trust and how your body feels things. I learned how you could quickly notice the energy in the room and even the temperature. That gave me a certain level of confidence which I felt I could take to the next level in front of the camera.”

Mark Ruffalo found, to his exhilaration, that being blind gave him new creative options. “The most remarkable thing about being blind was the freedom I felt as an actor,” he muses. “When I couldn’t see, I wasn’t worried about what my hands were doing or how I looked during the scene. It was like little kids say, ‘I’m going to close my eyes and the world can’t see me any more.’ You learned to trust what the director was seeing more than your own eyes.”

He continues: “Experiencing blindness also helped us to understand more about the story. In these workshops we were thrown out, blindfolded, onto a city street with 20 strangers, with only the sound of a bell to lead you. So what happens is that everyone starts holding onto each other and moving as a group. It immediately creates trust and community and I think that’s part of what Saramago was writing about.”

The Production

From the beginning, Fernando Meirelles knew that creating BLINDNESS on screen would, ironically, require truly original imagery that could pull audiences deep into the shock and disorientation of the characters and hold them riveted to this world. To design a film that could do that, the director brought with him many of his trusted and talented artistic crew from “City of God,” including: Oscar® nominated cinematographer César Charlone, who would use his experiences in the “blindness workshops” to help forge the film’s visual simulations of the “White Blindness”; Academy Award nominated editor Daniel Rezende, who worked closely with Meirelles to structure the film’s shifting, sinuous points of view; and production designer Tulé Peak, who turned a prison into the hastily crafted internment camp that critics of Saramago’s novel compared to Dante’s Inferno, and transformed a once cosmopolitan city into a ravaged urban wasteland for BLINDNESS.

Adhering to Saramago’s wish that the film, like the novel, be set in an unidentified city, which lends it a timeless universality, the production of BLINDNESS was shot in three different countries but no identifying signs were used. Most of the early exteriors were filmed in the large, vibrant city of Sao Paolo, Brazil, which also happens to be Meirelles’ home town; the middle section of the film, set in the asylum-turned-quarantine-camp, was shot in a defunct prison in Guelph, Canada; and the film’s climax, which unfolds against the shattered landscape of a completely disrupted metropolis, was shot in both Sao Paolo and Montevideo, Uruguay (a city suggested by cinematographer César Charlone who hails from Uruguay originally.)

A former architect, Meirelles is fascinated by structure but also by creative providence. He notes that his favorite moments in filmmaking are when a simple cut changes the meaning of a scene, when a camera movement suddenly seems to take on a soul of its own, when the music hits just the right tone for a scene, when an actor connects with a powerful emotion – and he is thrilled that all of these things happened on BLINDNESS.

Throughout, he was guided most powerfully by the quotation in the frontispiece of José Saramago’s novel (from the ancient Book of Exhortations): “If you can see, look. If you can look, observe.” After all, this story about blindness, Meirelles summarizes, “is really about learning to see.”

Production notes provided by Miramax Films.

Blindness

Starring: Mark Ruffalo, Julianne Moore, Gael Garcia Bernal, Danny Glover, Alice Braga

Directed by: Fernando Meirelles

Screenplay by: Don McKellar

Release Date: October 3, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for for violence including sexual assaults, and sexuality / nudity.

Studio: Miramax Films

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $3,351,751 (17.3%)

Foreign: $15,987,862 (82.7%)

Total: $19,339,613 (Worldwide)