Pediatric Alex, devasted since his wife margot was savagely murdered in the early days of their marriage eight years before, receives an anonymous email: when he clicks on the link indicated, he sees a woman’s face standing in a crowd and being filmed in real time. margot’s face…. is she still alive?

And why does she instruct him to tell no one? so many questions that our hero will not have time to consider: he barely even has time to raise the lid of this pandora’s box before the police reopen the case. and, eight years down the line, the cops are determined that he will take the rap for murder.

An interview with Guillaume Canet

After the success of his début feature My Idol, Guillaume Canet brings to the screen his adaptation of Harlan Coben’s bestseller Tell No One (translated into 27 languages, over 6 million copies sold worldwide). Canet co-wrote the screenplay with Philippe Lefebvre, his co-writer on My Idol.

This is your second feature and first book adaptation. Why this novel in particular?

Books people suggested to me or ideas of my own never aroused enough enthusiasm or passion in me to devote myself to the harrowing process that is making a film – writing, preparation, shooting… It takes two years out of your life. Just when I finally settled on an idea, I came across Tell No One, and for the first time I felt invested by the story. It contained many strong characters, which was perfect for me because I have a particular weakness: each time I meet an actor or actress I like, I want to work with them.

With this story, I had lots of parts to hand out! I also liked the accumulation of genres – thriller, love story, suspense – and I soon identified what I wanted to tweak in the characters to add the little offbeat touch that I was after, the nervous tics of Berléand’s character, for example. It was truly the first time I read something I hadn’t written that I could see myself directing. As I read the book, I could picture the film in my mind’s eye. I knew exactly what I wanted to do with it and, after we had written the script, as we were getting ready to shoot, I tried to ensure I never lost sight of those initial emotions.

Does adapting a novel create any particular constraints when writing the script?

I refused to accept any constraint. I told Harlan Coben right away why and how I wanted to adapt his book. I think that’s what won him over. He wasn’t at all happy with the US adaptation because they changed so much. I changed the ending but he loved what we came up with. He was very moved and told me that each change we made added something that wasn’t in the novel! It was very important for me that Harlan should like the movie. Philippe Lefebvre, my co-writer, and I constantly chose what was most credible for the characters and the plot. The only constraints sprang from the story itself.

There were things that were too easily resolved in the book and that wouldn’t work on film, like a character who says, “I heard that…” In a movie, that’s impossible. It has to be more grounded and that involves changing certain aspects of the plot. As for the rest, I gave myself a lot of freedom. I changed a lot of things, like introducing the character of Zach, the female torturer, who replaces the Asian guy in the book. I thought we’d seen plenty of guys like that in films. It’s more surprising to have a woman in that role – a woman torturing another woman has more impact in my view.

It feels like you inversed the codes of the genre. Instead of tacking a love story onto a thriller, it’s the love story that takes precedence here.

That was vital for me from the very beginning. It’s also what I told my producer, Alain Attal. What appealed to me about this movie was the love story. As a result, I didn’t aim to shoot it like a thriller. I wanted it to be sunny, for the action to take place in summer, with beautiful light. I didn’t want it to be anything like a thriller, full of sinister characters and music, where it’s raining the whole time. On the contrary, I wanted a real contrast between what Alex is going through and what is happening around him – sidewalk cafés, people having fun, a totally laidback ambiance. It’s summer, people are on vacation… I found it more interesting that the world around him should be at odds with his emotions and feelings.

In terms of the music, the restraint of Matthieu Chedid’s guitar playing contrasts with an otherwise romantic soundtrack.

It’s important to point out that the music was laid down in a single day. That’s what we had decided with Matthieu Chedid. When I called him, I knew I wanted something very simple. I had the songs in the back of my mind while I was writing the script but it took me a long time to realize what I wanted for the original score – something very cerebral, music that would follow a lone hero, which resulted in this single electric guitar with a kind of distorted sound. Matthieu’s initial reaction was that he didn’t have the time. He was planning a long recording session.

But I convinced him by explaining my idea, which he really liked, of recording the music like Ry Cooder did for Paris, Texas. I wanted him to play live over the movie, improvising totally. I screened the film for him in a studio. He sat down and played along. The music you hear comes from that single take. We wrapped it up in a single day’s work, going by instinct, and Matthieu’s genius and talent. The amazing thing is that the music is an integral part of the movie. You hardly notice it but it’s the most vital element. It builds raw emotion without being omnipresent. That was one of the best artistic encounters of my life.

Did you also choose François Cluzet by instinct?

Yes, I’ve been a fan of his for years and, like François Berléand not so long ago, I always thought he never got enough parts. I wanted someone who was as straight-up and spot-on as Patrick Dewaere – a real livewire. François doesn’t act, he lives things. This movie was made for François Cluzet. When I watch it now, I can’t imagine anybody else playing the part. I am eternally grateful to him for the energy he put into the film, and his patience, affability and availability at all times. He was throwing himself nude into a lake at 5 in the morning while the whole crew was huddled up in fleece jackets.

Then, I had him running for ten straight days and he never complained. He also has the most expressive eyes. When he sees Margot on the internet, the camera holds on him. He doesn’t move but his eyes reveal a whole range of emotions: surprise, doubt, suspicion and fear. For me, that’s huge. François nails it every time. He is always open to suggestions and he trusted me enormously. I have to say that, overall, I had only the very best on this film. All the actors gave me everything they had. Directing actors is one of the things I most like about filmmaking.

With such a great cast, the editing process must have thrown up some difficult choices.

Extremely difficult, which is why we edited for so long. Hervé de Luze, the editor, and I had to cut the movie down quite a lot and find its rhythm. The difficult thing was tying together all the leads that make book so good. If you take too many out, it becomes a process of deduction and the end-result is explicative, with no emotion. If you’re not lost in the plot, it’s pointless. After you’ve seen the movie so many times, you tend to want to simplify it, but you have to remember the emotion you felt first time round when you wanted to follow each and every lead.

On the other hand, the advantage of watching the film over and over is that you are able to cut out actors you admire, even in scenes you really liked, because you know there are plenty of others. It does them a favor, by the way, because you only keep the best scenes. One evening, I was talking with Matthieu Chedid, who said that the reason why Beatles songs are so short and so good is that they are so condensed. All that’s left is the best. I’ve always worked with music, so that really meant something for me. The next day, in editing, I took out quarter of an hour of the film. I understood what Matthieu was talking about. But it is very difficult and Hervé was a great help in making the necessary choices. He found a rhythm that I really liked for the film.

How did you manage to create the sense of intimacy in the opening scene?

Actually, that’s the only scene that wasn’t scripted. When Philippe Lefebvre and I started work on it, I sensed that we were slightly off. I didn’t like it. So I told all the actors not to pay any attention to the first scene in the script because we wouldn’t shoot it the way it was written. The night we shot it, we had a drink and I told them it was up to them to improvise. It was the first scene with them all together and we shot it in the first week, but I find that there’s nothing better than improv to get a handle on a character.

So I had a Steadycam moving round the table and told them to talk among themselves. They were free to say what they wanted. I wanted it to be alive, and for people to cut into each other’s conversations, like they do in Claude Sautet’s movies. You don’t get a sense of lines being spoken, just a bunch of friends shooting the breeze. That was my way of making the scene as credible as possible. At the beginning, they panicked, but they wound up having a lot of fun. Seeing Kristin Scott-Thomas rolling a joint was pretty memorable!

On set, you seem very “protective” of the actors.

“Starstruck”, I’d say! I was hugely grateful to them for giving so much energy to my picture and so I was as attentive to their needs as possible. I know how actors work and I knew that if I wanted them to give me what I wanted, I had to let them into my way of thinking. I had a very clear vision of the range of each character, so I could be very precise with the actors. For example, I wanted François Berléand to do the exact opposite of what he did in My Idol, where he just never stops talking. This time, I wanted him to talk slowly and express himself calmly and thoughtfully, but with a hint of a slightly obsessive nature. That’s what I had in mind, and as I’m pretty obsessive myself, I just don’t let up, even after several takes, until I get what I want.

The framing and camerawork in the film suggest you gave great thought to each shot.

When I write a scene, I visualize it immediately. I know exactly how I’ll shoot it, down to the nearest detail. On top of that, I operated the camera this time, which I couldn’t do on My Idol because I was also acting in it. I was lucky that we could afford to shoot with two cameras so I carried the handheld camera, which offers huge freedom to express yourself. By going right where you want to go, it allows you to be very fluid in your handling of the actors. There is no barrier between actors and camera, which was essential because the characters are the foundation of this movie. We only storyboarded one scene – when Alex runs across the Périphérique (Paris Beltway).

We had one day with eight cameras to get it in the can. We were incredibly lucky. No one was hurt and we got exactly what we wanted. Every scene in the rest of the picture was carefully broken down into shots. I’d arrive in the morning with the shot breakdown for the day and I’d hand it out to the heads of department. It didn’t always make them laugh, especially at Parc Monceau where I had 54 shots lined up in two days, which means shooting faster than on a TV movie.

We were full-on all day, but I was lucky to have an amazing crew of people who were willing, motivated, passionate and confident about the movie. My DP, Christophe Offenstein, is like a brother to me. We have worked together since my first short film. We’re very close. We like the same style, which helps with the framing. We each had a camera and it was very organic, like being two arms of the same body. That was particularly useful for a scene like the search of Alex’s house. We shot it without rehearsal – just blocked the actors and went for it because I wanted it to feel disorganized.

For once, we get the real Paris not the postcard version. Was location scouting an important phase for you?

Yes. With the production designer, Philippe Chiffre, I chose each location for the story it told. It’s no more expensive to find a place that tells a better story than another place. It’s very important to me. Parc Monceau, for example, was an obvious choice because of the lines of sight between the gates and the heart of the park, and also because it’s full of families and children. Also, the road layout made it easy to shoot the scene with the van just outside the park.

Also, I like to show different aspects of Paris -suburban housing projects, flea markets, the Beltway, Alex’s rundown neighborhood, and then swanky Avenue Montaigne, for the attorney, and Parc Monceau. You sense that he doesn’t quite belong there. When he turns up wearing Bruno’s jogging pants, he’s out of place in this uptown neighborhood. It’s also very exciting trying to film a location in order to bring to life the vision you had when you wrote the script.

Was it hard to find funding for the film?

I can’t say that it was hard, no. First reactions were generally positive because of the book, the story’s inherent quality. Also, feedback from my first film was good. For example, the TV channel M6, which coproduced My Idol, was very keen to be involved in this project. The only problem came in finding a distributor. Despite being a crucial part of the industry, some think there are only three actors in France! I hope that my choices will open their eyes and imaginations, so that they understand that audiences will go to see other actors. It would be a real tragedy to make films with the same actors every time.

François Cluzet

François Cluzet has worked extensively on stage and screen for major directors, such as Alain Françon, Jean-Michel Ribes, Claude Chabrol, Bertrand Tavernier, Bertrand Blier, and Claire Denis. He is equally at home in mainstream or arthouse pictures. L’été meurtrier (Jean Becker), Association de malfaiteurs (Claude Zidi) and Force Majeure (Pierre Jolivet) were among his first major successes. In Tell No One, he brings the wealth of his experience to the part of Alex.

In every shot

I like playing flawed characters – it makes them more human – so I appreciate it when they have a lot of screen time. It means you can really build the character. Even if, in this instance, Alex is a doctor who becomes a hero out of love, I always try to grasp every facet of the character, even the darker ones, and give him the necessary energy, enthusiasm and emotions so that the audience can see where he’s coming from.

Nobody is totally one-dimensional. I also liked the fact that a young director was given the means to succeed. The fact that the shoot was planned over fifteen weeks was a sign that the director’s vision was going to be very important, that Guillaume wouldn’t be easily satisfied and that he knew exactly where he wanted to take the picture. I knew we would have a lot of time and that we would be shooting a lot of footage. And as Guillaume wanted to be sure he had all he needed in editing – he who can do more can do less – we did indeed shoot a lot of footage.

Guillaume Canet, director

I soon got an insight into his dream of making a multi-faceted movie – an entertaining thriller that would also reflect his directorial vision. We’ve seen Guillaume the actor, but few people know what drives him. He’s a wonderful director, firstly because he offers the actors great scope and also because he possesses great vision. He gets things into the frame that other directors don’t even see. He’s also a perfectionist – the first on set and last to leave – and he gives it everything he’s got. He shows great leadership. He knows how to get the best out of his crew and give people confidence in their own ability. It’s an important asset for a director to be able to give, not just take.

A love story

Part of the reason that Guillaume chose this story is that, rather than being a thriller about drugs, money or power, it is a love story that takes you into the protagonists’ secret garden. I think he chose me because he thought I would be more sensitive to that aspect than some other actors. He was right. I make films to tell love stories, to love and be loved. And I’m not alone. Everything revolves around love.

Even though the film constantly juggles between action and emotion, with the possibility of Alex being reunited with his wife, on set Guillaume, as only the best directors can, was able to grasp the central dynamic of the picture. And that dynamic is the actors. Guillaume chose a cast, if not of tormented souls, at least of very sensitive actors. When he was directing me, even though he’d prepped everything, it was obvious where the film was going. He was divesting himself of it so that it became our film and not just the one he had on paper or in his mind.

The character

What appealed to me, since this was fiction, was that the guy’s love was completely out of the ordinary. It’s impossible to measure love, but let’s say that most humans love at 100 kilobars, and that for people who are really in love it reaches 260 kilobars, well, this guy loves at 1,000 kilobars. He can’t live without the woman he has lost because it’s more than a relationship, it’s his whole life, which he built with her and around her. When he loses her, it’s like he loses part of himself and could come crashing down at any moment. It’s beautiful to realize that because of his love for Margot he is the only one who believes she could still be alive. He still has so much love for her that he can explore that possibility. He can open his heart up again, even if it hurts.

The ultimate film role?

This film was an added extra. I had projects lined up, but when Guillaume offered me this part, I could see in his eyes that it was the part and I wanted to bring everything I had to the table, using all the experience I accumulated playing thankless supporting roles. I like that because I believe that actors must show what it is to be perverse, cowardly and mediocre and still be likable and entertaining, of course. That’s where things get difficult. That was my approach to Alex even though he was very present and a particularly gratifying character to play.

Preparation

I read the script twice and, as usual, jotted down questions that I talked over with Guillaume later. For example, we were on the trail of constant emotion, so that the character has a kind of restraint that makes him grow in stature. Alex is a graduate. He doesn’t show his feelings and finds it hard to talk about them. It would have been wrong to see him breaking down or weeping all the time. Guillaume and I were on the same wavelength. Guillaume is very open. He’s one of those people who is able to listen and make people listen to him.

Method

Once we’d talked through the script for three days, I let it simmer for a whole month, and I began the shoot with my whole curve in my mind. I always work that way. It’s kind of an innate logic that comes from my background in theatre. I must be aware of the character’s personal development so I can hit the right notes for each scene. Since we weren’t shooting chronologically, I had to know where Alex was at in each scene.

After a few days, I said to Guillaume, “I have a good sense of how you direct, and the crew and the overall atmosphere. It’s up there with the best experiences I’ve had in the business so far. I want to really push the envelope, so I need to be instinctive because the character doesn’t stop to admire himself. He’s damaged and keeps moving forward. He doesn’t look back. He’s the opposite of narcissistic.”

Anti-virtuosity

I wanted to avoid putting on a show. I hate virtuosity. It’s the opposite of acting because it’s not how people are, it stops people identifying with the character. You need to have an organic, irrational relationship with the character, or that’s what I think, at least. You have to let the audience glimpse their own potential, through you. You must never get trapped in the caricature of being “one in a million”. On the other hand, the film is a performance. Tell No One is very important to me because I had long dreamed of playing a guy who’s having a hard time of it. There’s always a tendency to over-act. Personifying a character doesn’t mean putting on a display, it means enriching from within. That’s the hard part. The rest is easier. The frame gives three-quarters of the character’s presence.

A physical part

That’s why it’s one of my favorite parts. I became a film actor to make action movies, not arthouse pictures. I was neither a film buff nor an intellectual. I’m a simple kind of guy and I say that without any embarrassment, quite the opposite. Suddenly, this part brought back my childhood dream. When I was at school, I knew I wanted to be an actor and I soon realized that I was good at fake fights and stunts. I thought that’s what I could expect in the movies. Then, drama school made me appreciate the quality of a text and lured me toward more sophisticated material. Now, I realize that the script isn’t everything. A very slender script can produce a masterpiece, as Buster Keaton showed. He started shooting with only part of the script completed. It’s audacious but it works. There is a kind of grace in being provocative and daring yourself to take risks.

The chase on the Beltway

When Guillaume said I’d be doing a lot of running, I was overjoyed. I did a lot of training but the important thing was to give it everything. The funny thing is that the actor who was chasing me couldn’t catch up with me. I was very pleased because that encapsulated the scene. Alex can’t be caught because he’s running toward the woman he loves.

Guillaume Canet and actors

Guillaume is very considerate and excessively respectful of actors, which is fine by me, of course. My aim is as logical as it is egotistical: I try to lead directors to believe that there is no one else but me for a part. Over time, and with experience and a little confidence, I no longer focus exclusively on my part, but on the need to make the best possible picture and therefore, with the director, find the ideal way of playing a part.

When you read the script of Tell No One, you see right away that this guy, who is on screen the whole time, could easily turn people off by being too virtuous and that we couldn’t allow that to happen even for a second. On the contrary, he had to become more endearing as well as excessively reserved. It is his reserve and emotions that enable the audience to relate to him. So, I was in my element and I also felt a hint of competitiveness. I love that. The best way to captivate an audience is through a kind of collective inspiration. When you have a crew that is right behind the director, a good producer, a good script and good actors, everybody reaches for the same goal: to beat their personal best.

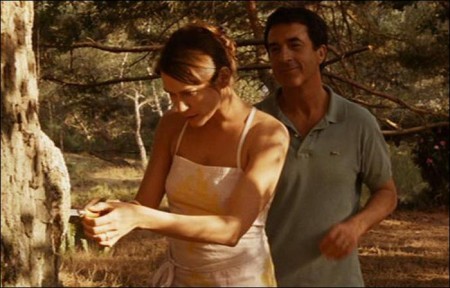

The opening scene

Guillaume wanted to capture the feeling of a group of friends in order to emphasize the openness of their relationship to each other. He told us not to be afraid of going off at a tangent, so we really let it rip. The scene is supposed to be ten years earlier, so I had my hair done differently. I also had a prosthesis in my mouth, which is supposed to make me look younger. All it did was hurt me. I took it out and passed it round the table. Everybody started laughing and we had a blast. Nobody felt superior. We were all pulling together.

Two generations of actors

In thirty years, things have changed enormously. Now, being aware of your “scene partner” is absolutely vital.

The final scene

I prepared for it mentally, like an athlete almost. It was scheduled for quite early in the shoot and Guillaume had to bring it forward even more, but that wasn’t a huge problem. I knew that it all came down to being ready when the camera started rolling. At times like that, my experience comes in handy. The emotion had to be there quite early in the scene, so I made the crew very aware of the concentration level I would need.

Playing pain is easy. You can do it on the subway, but to make the performance instinctive rather than cerebral, I needed a little time. I started walking round the tree in total silence, with everybody waiting for me. I sensed that I couldn’t let anybody down. The emotion gradually rose within. I recalled a few painful moments to capture a kind of vulnerability and the emotion swelled up in me. I had to feel that pain as hard as I could possibly bear, and it had to be ready to burst out and be totally overwhelming. But not before the camera started rolling. The really beautiful moment is the first flicker of emotion. Otherwise, you can just smack a guy around the head and film him in pain. Then, with time slipping by and the sun declining… “Action!”

Production notes provided by Revolution Studios.

Tell No One (Ne Le Dis A Personne)

Starring: François Cluzet, Marie-Josee Croze, Andre Dussolier, Kristin Scott-Thomas, François Berleand, Nathalie Baye, Jean Rochefort, Guillaume Canet

Directed by: Guillaume Canet

Screenplay by: Guillaume Canet

Release Date: June 15th, 2007

MPAA Rating: None.

Studio: Revolution Studios

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $5,674,452 (17.3%)

Foreign: $27,205,761 (82.7%)

Total: $32,880,213 (Worldwide)