In the early ’70s, police corruption was rampant in New York City. The Vietnam War was taking a devastating toll overseas and at home. Soldiers were brought back to the U.S. either in body bags or addicted to an imported opiate called heroin-which they shared with curious experimenters who became instantly hooked. With the assistance of law enforcement, the mafia operated with relative impunity in this noncompetitive market, selling thousands of kilos of smack to addicts hungry for their product.

A privileged and untouchable class of white men paid hundreds of millions to New York’s judges, lawyers and cops to keep quiet about this mutually beneficial relationship. La Cosa Nostra and their underlings were unbeatable. Until a black entrepreneur named Frank Lucas (Washington) took over the game.

Nobody used to notice Frank, the quiet apprentice to Bumpy Johnson, one of the inner city’s leading postwar black crime bosses. But when his boss suddenly dies, Lucas exploits the opening in the power structure to build his own empire and create his own version of the American success story.

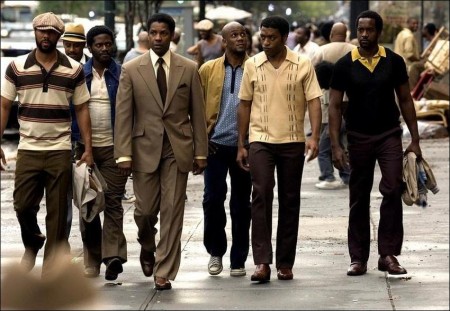

Though he had never been to school, Lucas had years of knowledge gleaned from the streets. He applied this-along with ingenuity and a strict business ethic-to come to rule the inner-city drug trade, flooding the streets with a purer product at a better price. Lucas outplays all of the leading crime syndicates and becomes not only one of the city’s mainline corrupters, but part of its circle of civic superstars.

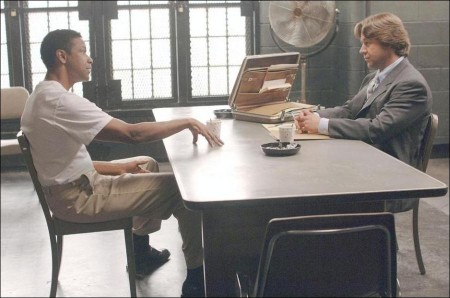

Hard-nosed cop Richie Roberts (Crowe) is close enough to the streets to feel a shift of control in the drug underworld. Roberts believes someone is climbing the rungs above the known Mafia families and starts to suspect that a black power player has come from nowhere to dominate the scene. Both Lucas and Roberts share a rigorous ethical code that sets them apart from their own colleagues, making them lone figures on opposite sides of the law. The destinies of these two men will become intertwined as they approach a confrontation that will not only change their own lives, but alter the destiny of an entire generation of New York City.

Academy Award winners Russell Crowe (Gladiator, The Insider) and Denzel Washington (Training Day, The Hurricane) join Oscar-winning producer Brian Grazer (A Beautiful Mind, Cinderella Man), director / producer Ridley Scott (Gladiator, Black Hawk Down) and Academy Award-winning screenwriter Steven Zaillian (Schindler’s List, Gangs of New York) for a cinematic event that tells the true juggernaut success story of a cult superstar from the streets of 1970s Harlem who rose to the heights of power by becoming the most ruthless figure in his business…and was taken down by an outcast cop driven to bring justice to the streets: American Gangster.

Filmed on location in New York and Thailand, American Gangster spans the years during the height of the Vietnam War, 1968-1974. Lucas and Roberts’ efforts in the post-Boomer society-separately and, eventually together-would mark the beginning of the end of an era of complicit lawlessness that claimed thousands of lives. And in one corrupt city during one turbulent time, two men living on different sides of the American Dream had no idea they would move from mortal enemies to reluctant allies on the same side of the law.

The Return of Superfly: American Gangster is Created

“My company sells a product that’s better than the competition at a price that’s lower than the competition.” – Frank Lucas

The legend of heroin smuggler/family man/death dealer/civic leader Frank Lucas was first chronicled in a New York Magazine article by journalist Mark Jacobson seven years ago. In 2000, executive producer Nicholas Pileggi-who co-wrote the screenplays for Goodfellas and Casino with Martin Scorsese-introduced Jacobson to Lucas, thus beginning a journey in which Lucas recounted his outrageous rise and fall to the journalist. From watching his cousin murdered by the KKK in La Grange, North Carolina, to earning mind-boggling figures in drug sales to facing a lifetime in prison, Lucas had one stunner of a true tale.

Jacobson’s subsequent “The Return of Superfly” unfolded the complex story of a desperately poor sharecropper who moved to Harlem and slowly bypassed the usual suspects of its burgeoning heroin scene to rule a New York City empire. Through selling a purer product at a cheaper price to thousands of addicts in the Vietnam-era streets, Lucas amassed a fortune calculated in the tens of millions-and the eventual attention of the law. Had he not been pushing an illegal, deadly substance new to this country, Lucas would have assuredly been celebrated as one of the keenest businessmen of the decade, if not the century, for his family-run enterprise.

Growing up penniless in a small Southern town, Lucas arrived in New York in 1946 as a self-described “different sonofabitch.” For two decades, he worked side-by-side with Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson (the inspiration for the black godfather of the ’70s Shaft films), serving as the kingpin’s right-hand man until Johnson’s death in 1968-tutored in the ways of gangsters like Frank Costello and Lucky Luciano. And upon Johnson’s death, Lucas seized the reins. He changed the name of the game to the hot new import heroin and immediately put his stamp on the city-with a gun to the head of anyone who dared challenge him.

Fascinated by Jacobson’s article, Academy Award-winning producer Brian Grazer optioned the project for Imagine Entertainment and met with Pileggi and Lucas to discuss the gangster’s exploits. Many of Grazer’s recent celebrated films have been inspired by real-life subjects overcoming the seemingly insurmountable-from 8 Mile and Friday Night Lights to A Beautiful Mind and Cinderella Man. Grazer viewed Lucas’ story as a metaphor for the greediness of white-collar capitalism and had, admittedly, never heard anything quite like it.

Grazer was fascinated by the cautionary tale of a man with “the dream of corporate America who found a way to make a deal with individuals in Southeast Asia that could lead him to the highest grade of heroin.” He continues, “After he had this heroin, he would make a deal with U.S. military officers to import it in body bags of U.S. soldiers traveling from Vietnam back into America [the so-called Cadaver Connection]. I thought that was a remarkable, inescapable and interesting idea.” The producer would take this option and turn to veteran screenwriter Steven Zaillian to pen a script based on Lucas’ life.

Oscar winner Zaillian-responsible for such landmark cinematic interpretations as Steven Spielberg’s directorial masterpiece Schindler’s List and Martin Scorsese’s lauded Gangs of New York-would spend months with Lucas and his former pursuer (now retained attorney) Richie Roberts to give shape to their improbable tale that spanned decades. Zaillian would also become fascinated with the unlikely relationship between this multimillionaire thug/entrepreneur and this complicated cop-turned-prosecutor. He was certain to weave a shattering parable that didn’t just dramatize Lucas’ rise and fall but told of the juxtaposed path of his chief tracker and nemesis.

Roberts, who spent the late 1960s to early ’70s as an Essex County, New York, detective, was the man ultimately responsible for bringing down the folk hero. Grazer and Zaillian thought that what made this story especially compelling was not just Lucas-who lived by a strict code of family and community as he pushed poison into thousands of lives in the very community in which he lived-but also Roberts, who found his own destiny interwoven with that of the drug kingpin.

The officer of Zaillian’s screenplay was a purported ladies’ man who struggled to keep his personal life in check, while he lived and breathed the strong arm of the law. One of the few lawmen at the time not pulled into the temptation of a life on the take, Roberts (or at least Zaillian’s incarnation of this hardened cop) needed to face the exact opposite issues of the writer’s Lucas.

First attached to the project was director Antoine Fuqua, who had directed Denzel Washington in his 2001 Oscar-winning portrayal of corrupt LAPD narcotics officer Alonzo Harris in Training Day. Washington, initially resistant to portray a man whose complex rise to power meant the death of so many, was captivated by the script and came aboard for the lead role. He was intrigued by the intricate story of Lucas’ life, and believed the businessman who had hurt so many was, in fact, trying to redeem himself through years of penitence. The actor would have to wait a few more years to take the role to the screen.

Prior to the start of principal photography in 2004, Universal Pictures stopped the development of the project. Remembers producer Grazer: “Everything just flatlined, and I was devastated for about a week. But I still really believed in this project.”

Grazer offers, “I charged forward with all my energy and full commitment to get it made. I’d taken the script to Ridley Scott seven or eight times, and he always liked it, but the timing was never right for him. This time-the ninth or tenth time-he said, `Yes.’”

The British filmmaker-known for his four decades of creations from science-fiction films Blade Runner and Alien to dramas Black Hawk Down, Gladiator, Thelma & Louise and Hannibal-was drawn to the muddy ethics and ultimate paradox of the two protagonists in Zaillian’s story.

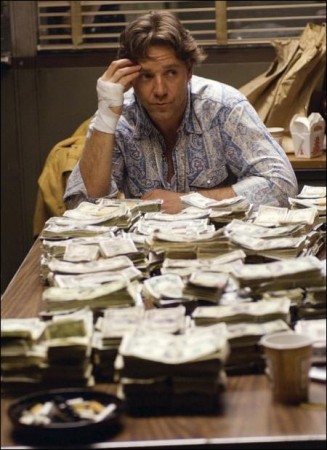

Indeed, Scott had encouraged Zaillian to flesh out more of Richie Roberts’ tale in the previous versions of the script he read. Scott was quite interested in the paradox that, while Lucas was dealing drugs-yet reportedly had a sterling home life-Roberts had a personal life that was “shot to hell” and “he became infamous fairly early on in his career within the police department when he found a million dollars in the trunk of a car on a stakeout. After he turned it in, he could no longer be trusted inside the department.”

The director felt the double-helix dynamic was worth investigating, and, that if he were to tackle the project, he would “explore two universes-hopefully making them both fascinating and gradually bringing them together. They’re carefully intercut, because every time you intercut between these two worlds, they’re getting closer together.” He would do the picture if his frequent partner joined him in the effort, proposing that Crowe play the part of Richie Roberts and that Washington rejoin.

With Crowe and Scott on board, Washington found he couldn’t say no to preparing to play Frank Lucas one more time. The actor states, “Brian came to me and said, `I’ve got Ridley.’ Well, Ridley’s one of the great filmmakers of our time, so you can’t say `No.’” He would finally begin playing the man who had grown from chicken thief to the king of Harlem.

To prepare for the role, Washington acknowledges that he, “got in a room with Frank, turned on the recorder and talked with him. I didn’t try to imitate him, necessarily, but Frank’s such a charmer; that’s key to his character. I played Rubin `Hurricane’ Carter and did the same thing with him-just hung out with him, got him alone and got the truth-or, hopefully, got some version of it. But with Frank, I said, `Don’t tell me anything I don’t need to know. I don’t want to have to testify.’”

In his research, the New York native learned more than he ever thought possible about the drug trade, specifically, the Country Boys’ Blue Magic. “In those days, as the story is told, heroin was sold for $50,000 to $60,000 a kilo at 50 percent, 60 percent purity,” he comments. “Frank found it 100-percent pure for $4,200 a kilo and sold it on the street at a higher purity and lower price than his competition. You can do the math. He made an incredible amount of money, at one point claiming about a million dollars a day himself.”

Continues Washington, “What interested me in the story was not to glorify a drug dealer, and I told Frank that when I met him.” Interestingly, Washington wrote the biblical passage Isaiah 48:22 [“There is no peace, saith the Lord, unto the wicked”] on his shooting script to remind him of Lucas’ journey and quest for redemption.

Game for a third collaboration with the director and a third with producer Grazer, Crowe signed on for the part of the complicated and hardened police officer Roberts. He was interested in how Zaillian’s story captured the time and place in which the corrupt New York City, the borough of Harlem and the slightly simpler world of New Jersey operated as satellites for one another in the drug-fueled era. Corruption had become so rampant within the Narcotics Special Investigations Unit (SIU) community, according to journalist Mark Jacobson in “The Return of Superfly,” that “by 1977, 52 out of 70 officers who’d worked in the unit were either in jail or under indictment.” Roberts was the exception to the norm, and Crowe admired what he learned of the man.

Recalling Grazer’s initial discussions with him, Crowe says, “I’d read five or six different versions of the script, and I knew which way I would lean, but it all comes down to the captain of the ship. I’d gotten a call from Brian on Friday, and on Saturday I got a call from Ridley about something else, and I asked if he’d read the latest draft. He said he had, and he’d loved it. So, I said, `Do you think we’d appear greedy if we did another film together so quickly?’ He said, `Who cares?’”

However, making a movie about real people, Crowe notes, is not the same as making a documentary about their lives. “Our script breaks down a period, and the timeline is condensed to tell a story,” says the actor. “There are things we have Richie do in the movie that he didn’t do. Everything about him is contradictory. None of his real story has traditional elements-and he’s not somebody you can easily categorize. When it comes down to it, you’re doing an impression.”

With the two lead talents in place, the production began the search for the cast of actors who would fill out an all-star ensemble with more than 30 principal roles.

Country Boys and Lawless Men

“Judges, lawyers, cops, politicians…stop bringing dope into this country, about 100,000 people will be out of jobs.” – Richie Roberts

To perform opposite Washington and Crowe in American Gangster, Scott and Grazer recruited a top-notch group of actors. For Lucas’ family, they would need to cast a crew of brothers and cousins whom he brought to Harlem to help sell product. For the roles of the cult figure’s heroin-dealing ring known as the Country Boys-so named because of their upbringing in the backwoods of North Carolina-the production looked to a mix of talent with backgrounds ranging from classical training to hip-hop performance. The real names and relations were changed for the film’s screenplay.

The lead Country Boy, Lucas’ younger brother and right-hand man, Huey, was played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, a British actor with an impressive American film resume. “I’d worked with Chiwetel on Inside Man,” says Grazer. “He played Denzel’s partner in that movie, so they already had a terrific working relationship. Even though he’s British, he slips into an American character like he was born in this country. His character is very flamboyant and unpredictable, which makes an interesting contrast to Frank’s cool and low-key personality.”

Other Lucas family members prominently featured in the film include a couple of best-selling artists relatively new to film-rapper Common as Frank’s brother Turner and rising hip-hop artist T.I. as Frank’s impressionable nephew Stevie. Scott, aware that these performers might not warm to the slow pace of making movies, was impressed by how they adapted to the unique demands of film work. He commends, “It seems that acting is a natural step from singing. We see some great performances from Common and T.I.”

Matriarch to the clan is legendary actress Ruby Dee, portraying Mama Lucas. The recipient of the John F. Kennedy Center Honors and Screen Actors Guild’s Life Achievement Award, Dee served as inspiration to many of those on set. For the Harlem native, revisiting the world of her youth proved helpful insight for all with whom she worked. The actress notes, “The time of Frank Lucas that American Gangster is about doesn’t seem as much of a film to me as it does more of a memory. Gangsters played a very important role in the life of the community, because they were part of the community. They controlled the rackets.”

As a child, she lived in an apartment building on 137th Street and 7th Avenue. Of that time, Dee recalls, “People who looked like Denzel would come to the door in twos or threes, and they would give you a greeting and hand you a shopping bag. In there would be a turkey at Thanksgiving; at Christmas there would be toys.” Only later in life would she learn that they weren’t just helpful citizens; there was a “political connection to the gangster element.”

Oscar winner Cuba Gooding, Jr., was tasked to play Lucas’ major rival in the heroin trade, Nicky Barnes. Also a big-time player in the Harlem drug land, Barnes, like Lucas, would eventually turn state’s evidence after his arrest. But until that time, he wanted all that Lucas had and more, once appearing on the cover of The New York Times Magazine asserting that he was “Mr. Untouchable.” Gooding was curious about the role these dealers played in New York City in the early ’70s. He summarizes Barnes and Lucas’ appeal: “These cats were looked upon as the true celebrities. Today we have sports celebrities like the Mets and the Yankees or actors, but back then you had the drug dealers. They were the ones that were directly connected to the inner city and the people.”

Typifying the mafioso of the day, Armand Assante plays Dominic Cattano, the powerful thorn in the side of Lucas who, like everyone else, is shocked that a black power player has usurped the structure and brought less-expensive, purer heroin to the streets. Assante offers, “Cattano is a powerful man who believes that he and his business are above the law and any competition. Shaken by what he’s seen in Frank Lucas, he attempts to work out a mutually beneficial relationship. After Frank declines, Cattano will not stop until he’s brought down the full force of his empire upon him.”

Another thorn in Lucas’ (and ultimately Roberts’) side is the on-the-take NYPD detective Trupo, played by Josh Brolin. The Ridley Scott-termed “badass cop” will let anyone sell drugs on his streets, as long as they give him a hefty kickback. Brolin was curious to examine the mind of this “criminal with a badge” who personified the police corruption of the day. To inform his character, he recalled a conversation with a seasoned police officer, who candidly told him, “All you had to tell a drug dealer was, `All I have to do is shoot you, put the gun in your hand, and I’m gonna get a medal. That’s it. It’s that simple.’ Back then, there weren’t a lot of drug dealers or gangsters who killed cops, that was just off-limits; you just didn’t do it.”

Adding to the ensemble was Lucas’ wife, Eva, the former Miss Puerto Rico whom he gently seduces into his life of crime. Scott wanted a young woman with “pleasant innocence” for the part, and turned to Lymari Nadal, an ingénue from Puerto Rico who had earned her master’s degree in chemistry before venturing into the acting field. Notes Nadal, “I had a chance to go through the script and make choices about Eva before I met the real person [naturally, her name had been changed for the script]. I’m trying to honor the way she sees her life. The most important things for her, I think, are her love story and how much she could buy, or how much money she could have.”

Compliments Denzel Washington of the fellow actors who play Lucas’ family and competition, “When I took a look at the cast list, I said, `Man, these guys are putting this together here.’ Actors like Ruby Dee, who plays my mom…she’s a legend. Fantastic actors like Armand Assante; Cuba Gooding, Jr.; Clarence Williams III; Chiwetel-this was an unusually interesting group.”

On the parallel side of Frank’s universe lived Richie Roberts and the players in his world. Once Richie turns over a million dollars in found drug money to the authorities-much to the chagrin of his heroin-sampling partner, Javier Rivera (John Ortiz)-he is a marked man, distrusted by dirty cops and crooks alike.

Given the chance to run a division of the Essex County SIU, Roberts must select an elite group of undercover detectives who are as savvy and streetwise as the criminals they pursue. For these roles, Scott and Grazer looked to veteran character actors John Hawkes and Yul Vazquez, as well as another music-world luminary, RZA-co-founder of the iconic hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan. RZA, who had made his mark in films such as the Clive Owen-Jennifer Aniston thriller Derailed, had a long association with Grazer; the two worked together on 8 Mile.

It was interesting for the new SIU team to learn that many narcotics officers work this job because of the rush they get from it; some actually describe the work as a drug itself. Hawkes, who plays Detective Spearman, understood that the bureau-headed by veteran character actor Ted Levine as Lou Toback-was “a precursor to the DEA, one of the first federal drug task forces.” The actor explains, “Richie must choose some honest cops, and he finds me, looking like a criminal. I tell him, `I won’t come with you unless you take my other guys, too.’ He doesn’t know them-Jones and Abruzzo, played by Yul Vazquez and RZA. We just look like complete derelict, crazy men and turn out to be really great cops.”

“They’re a motley bunch,” Crowe says of his crime-fighting teammates. “We did a lot of improv with dialogue, because Ridley gives his actors a lot of space to create. He wanted more out of these situations where they’re together trying to figure out how all the pieces fit and who these blokes (in Lucas’ criminal underworld) are. In these performances, you had to be on your toes and know your character and the situation, because it’s all about the interaction.”

While Roberts’ professional life is taking off, his personal one is crumbling around him. Chosen to perform as Laurie, the wife in the process of leaving him, was Carla Gugino. The actress felt sympathy for the tough-talking New Yorker who has had enough of her cheating husband and finally decides to move on. “There’s absolutely a genuine love there,” she says, “but it’s the kind of relationship that’s impossible, because he’s a total philanderer. She’s tried to think that he might change, and realizes that he won’t-and ultimately decides to take her son to Las Vegas to live with her sister.” This was yet another blow to Richie and an even greater reason for him to become obsessed with bringing down the Lucas empire.

Key cast members chosen, Scott, Grazer and five-time Scott production-design partner Arthur Max would begin the painstaking process of re-creating Harlem and Vietnam in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Capturing the Vietnam Era: Filming in New York and Thailand

“I have to see everything, because it’s my homework. I see the inside of places; I see the inside of houses…how people live and dress. I glom on to that kind of information.” – Ridley Scott

From imagining the dystopian Los Angeles of 2019 in Blade Runner to Maximus’ ancient Rome in Gladiator, director Ridley Scott has forged a career since his earliest days in advertising as an uncompromising aesthetic master. Re-creating the universe of Richie Roberts and Frank Lucas’ 1970s-era Harlem would prove quite an ambitious task for all involved in the American Gangster team.

To the art-student-turned-director who had spent decades making films, however, nothing seemed impossible-not even lensing in 152 different locations with almost 100 actors in speaking roles. Commends producer Grazer, “Ridley creates worlds, and he gets people on screen to have a tremendous connectivity. He can breathe life into the words on a page and make them become three-dimensional.”

American Gangster is one of the most sprawling tales ever told in and about New York City. And while Frank Lucas operated his drug empire primarily out of Harlem, the production took place in all five boroughs of New York City, primarily in practical locations. There were also a few days’ filming in upstate New York and suburban Long Island.

While there are inherent difficulties in re-creating a city from three decades ago, the director knew New York City quite well; indeed, he had spent much time in the Bowery District in the early ’60s. Scott states, “I knew what to do with Harlem…finding little nooks and corners and crannies of what Harlem must have been.” His imaging for the film was to “take big, wide shots to get a big picture of Harlem.”

Primarily using handheld cameras, cinematographer Harris Savides kept pace with what Scott described as a “guerilla filmmaking” style. Savides rose to the challenge as the director worked with his usual propensity for multicamera setups and shot nearly the entire film on practical locations.

Another longtime Scott collaborator, Arthur Max, turned his production design skills toward exhaustive location scouting to find the parts of New York that could still resemble the city of the early 1970s. He found that Harlem had changed much since the days of Frank and the Country Boys. To capture the look and feel of the neighborhood of the period, the crew shot 20 blocks north of Lucas’ infamous 116th Street, lensing on 136th Street and switching those street signs to complete the look.

For the real Frank Lucas, filming in Harlem was a revisit to his days of glory- though not all his old neighbors were ready to give him a hero’s welcome. On set nearly every day Washington worked, Lucas sat in his wheelchair, surrounded by his immediate family, and reminisced. “Yeah, he looks like Babyface (one of the SIU’s not-so-finest), right down to the leather coat,” Lucas acknowledged while pointing at Josh Brolin in character. “He even got that walk down, and they got him driving that Shelby car like he did.”

Washington, who was born in upstate New York and attended college at Fordham University in Manhattan, felt at home in this historic capital of urban black culture. “I’ve had a chance to film all over this city with Spike [Lee],” says the actor. “In fact, we shot in the same church that we used for this movie. It’s nice to walk some of the same streets I walked as a child; people walk up that actually know me from back in those days.”

Filming in the midst of the 100-degree-plus summer left at least one member of the cast feeling slightly less nostalgic. “Trying to run up and down stairs in ’70s-cut Levis in a New York heat wave,” Crowe says, shaking his head. “I ran 54 steps up and 54 down and another 75 up again, one day. After 10 flights, your jeans are completely wet, and they’re so tight that they cut off your circulation.”

Production began in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, a newly gentrified section of the venerable borough where artists and musicians vie for high-priced lofts and condo-converted warehouses. The filmmakers were searching for an older, seedier section of the neighborhood and found a scrap-metal shop to serve as a site for a money drop in which Roberts and his partner conducted surveillance. Filming would return to this neighborhood, near Myrtle and Broadway, on three other occasions for subsequent sequences involving drug deals and undercover action.

While the production relocated almost daily-if not several times daily-one of the lengthiest stays was at the Governors Island location, to which the crew ferried each morning for almost a week. The island, a few miles across New York Harbor from the Statue of Liberty, is a former army barracks and training base that transferred from U.S. government hands back to New York State in 2003. The high-rise buildings that once housed military personnel have been vacant ever since. These apartments served the production for several interior sets, including Lucas’ infamous heroin-cutting den and the housing projects in which the final drug busts take place.

For exterior shots, the Marlboro Projects in the Gravesend section of south Brooklyn provided visuals of the 28 buildings that offer low-cost housing to 1,700 families. It is also home to numerous drug dealers, petty thieves and gangs. The film company spent two days there filming Roberts’ rescue of his drug-addicted partner, Javier (John Ortiz), from a mob after the addled police detective killed his supplier.

Fortunately, not all the locations were quite so gritty. Among the most beautiful was the estate that stood in for the home of Italian mobster Dominic Cattano (Armand Assante) in Old Westbury Gardens, Long Island. The Gardens themselves are 160 acres and surround a mansion built in 1906 for steel-business magnate John Phipps.

The site of Lucas’ own country estate was only slightly less grand. Briarcliff Manor, New York-a suburb about an hour north of Manhattan-was home to such old-money families as the Astors, the Vanderbilts and the Rockefellers. Two properties were used as sets there: one that served as the stately home Lucas buys for his family after he’s brought them north, and the second, a far a more modest spread, that served as the family’s North Carolina farm.

One of the biggest scenes shot in New York was a re-creation of the first Ali-Frazier fight at Madison Square Garden, when Lucas tips off Roberts-by sitting in the best seats in the house and wearing an extravagant chinchilla coat-that he might be the biggest new hustler in the drug game. Filmed at the 16,000-seat Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum on Long Island, the arena was filled with extras in period costumes-along with many famous faces who were actually in the ringside seats that historic night. At least, they looked like the actual celebrities.

“It took us weeks and weeks to find the right people for the celebrity look-alikes,” explains extras casting director Billy Dowd. “We went to celebrity look-alike agencies, put an ad in Show Business and Backstage, newspapers, Craigslist. Some were very hard to find; some walked right into our offices, and we cast them immediately.” Fortuitously, the son of Arthur Mercante, the actual man who refereed the legendary fight, played his father in the ring.

If finding the right people to stand in as celebrity extras was a challenge, outfitting nearly 1,000 extras, dressed to the nines for the fight of the decade, was no less a feat for costume designer Janty Yates. “We used a lot of photos from the real event and made replicas of a lot of those outfits for our featured group,” Yates explains. “We looked all over New York and had to corner the market on tuxedos and cocktail dresses from the period to dress our crowd.”

Stateside filming wrapped in New York and moved to northern Thailand, where Scott would re-create Lucas’ time in Southeast Asia. Ingeniously, the gangster had moved heroin shipments on military planes and then sent them to Eastern Seaboard bases with the help of U.S. Army soldiers whom Lucas had on the take. His crew constructed a scheme in which false bottoms were put in coffins that concealed six to eight kilos of heroin; the first trip alone yielded a take of 132 kilos.

In this area of Thailand, approximately two hours north of the city of Chiang Mai, scenes from Lucas’ trip to the opium-rich poppy fields of the Golden Triangle-also known as the intersection among Burma, Thailand and Laos-were filmed. This region in Southeast Asia is where the majority of the world’s poppy crop was grown 30 years ago.

Production designer Max’s team built a traditional Thai village and rice barn in the middle of a peanut field to represent the opium-processing center where Lucas seals his first deals with military drug suppliers, who were likely members of Chiang Kai-shek’s former Kuomintang army. There, Lucas makes the connections that will allow him to undercut every other drug wholesaler by buying directly from the source and providing a purer product.

In preparation for filming the scenes in which Lucas meets with his military cousin-by-marriage in Bangkok to secure the trip to the opium fields and meet this supplier, Max recreated the market scenes in the city of Chiang Mai. Matters were not helped by the fact that the government had recently been disbanded in a coup d’etat, and the production had to rely on local workers and a changing political structure to create a city with never-ending nightlife that served as a docking station for service members. Complete with pulsing neon, fluorescent lighting and multilayered sets, one doesn’t have to look closely to see the futuristic Asian influences of Blade Runner in this design.

Sounds of a Generation: Music of American Gangster

“Please don’t compare me to other rappers. Compare me to trappers. I’m more Frank Lucas than Ludacris. And Lude is my dude, I ain’t trying to dis. Just like Frank Lucas is cool, but I ain’t tryin’ to snitch. -Jay-Z, “No Hook” from Roc-A-Fella Records’ album “American Gangster”

Director/producer Scott and producer Grazer were adamant that the soundtrack for their drama was intercut with the great music that was the reality of Frank Lucas’ world. Grazer offers, “I wanted the film to be encased with music like B-sides of albums from the era. As much as I like the songs we recognize, I wanted to introduce a visual and sonic world that is a contained entity of the ’70s.” Likewise, Scott felt it was vital to have “the brand of music that was Harlem at the time.”

As the film’s music supervisor, Kathy Nelson, explains, “This was probably one of the richest eras of music. It was right at the beginning of the whole funk scene. Harlem was as much about music as it was about drugs and whatever else was going on. The music scene was really exploding, particularly in the R & B and funk areas.”

Music of the soundtrack offers an album full of not just funk and R & B, but also classic blues, soul and hip-hop. Tracks from blues originator John Lee Hooker; guitar legend Bobby Womack; rhythm, country and blues greats The Staple Singers; gritty, ill-fated soul duo Sam & Dave; and multihyphenate blues man Lowell Fulson permeate the film.

Drawing upon inspiration from such legends, the first single released, “Do You Feel Me,” written by legendary Grammy-winning songwriter Diane Warren and performed by platinum artist Anthony Hamilton-a musician known for his raw emotions and smooth sounds-reflects a 2007 perspective on the world influenced by Frank “Haint of Harlem” Lucas. It serves to introduce him to his bride-to-be, Lydia, in Small’s Paradise, a nightclub filled with the smooth, dangerous characters one would easily find at the hottest club in town back in the day.

An event no one involved in the production expected was that the film would have such a profound effect on one hip-hop mogul that he would create an album of entirely original material to be released in conjunction with American Gangster. After he viewed an early screening, rap superstar and president of Def Jam Records Jay-Z was deeply moved by Denzel Washington’s portrayal of Frank Lucas. So much so, he felt inspired to create original material that drew upon his past experiences as a hustler and drug dealer, a life somewhat parallel to the ’70s gangster Lucas.

The artist notes that the film sparked an unexpected burst of creativity from him, because it felt like “this guy was looking in my window.” He was so affected by this true story, because where he was from, “we had never seen someone ascend to those heights. It was unfathomable to be over the mob, for people coming from these neighborhoods. I felt a sense of being proud, but at the same time, it was illegal activity with human beings on the other side of this tale.”

The film’s trailer was already using “Heart of the City,” an older song by Jay-Z, when Jay-Z made his decision. For the conceptual album he wrote to accompany Gangster, the singer/songwriter notes that he wanted to go a different direction from previous work. He admits that he is taking the listener on a musical journey that speaks to the harsh reality of the drug trade occurring in our nation. In the songs, the rapper articulates a tale that follows the conflicting lure of a gangster’s life and stands as an example of one who chose to leave the danger of those streets behind for a career in music.

The Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn native has become one of the most successful black entrepreneurs of our day; his difficult journey is not lost in this album. To complement the story of the film, Jay-Z takes the audience into a world rich in family, thrilling in hustling and descriptive in the brutalizing effects of drugs on an inner-city community in which “the game and the life take over.” He, like Frank Lucas, knows all too well the dizzying effects of becoming “addicted to what’s happening.”

****

Principal photography wrapped, editing finished and music scored, Scott, Grazer and the cast and crew find the end of a journey that started with a young North Carolina sharecropper who had risen to the heights of power in New York City… only to have the fruits of his labor taken away by a hard-edged cop who grappled with demons of his own.

Best concluding our story is the American Gangster’s director. Of his hopes for audiences who experience the film, Ridley Scott reflects: “I hope they feel fully engaged by these two great actors and how they suck you into the world and evolution of these two characters.”

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

American Gangster

Starring: Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Josh Brolin, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Carla Gugino, Common, TI, RZA, Ted Levine, John Ortiz, Yul Vazquez, Lymari Nadal

Directed by: Ridley Scott

Screenplay by: Steven Zallian

Release Date: November 2, 2007

MPAA Rating: R for violence, pervasive drug content and language, nudity and sexuality.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $130,164,645 (49.0%)

Foreign: $135,533,180 (51.0%)

Total: $265,697,825 (Worldwide)