Tagline: If you look close enough, you’ll find everyone has a weak spot.

When Ted Crawford (Anthony Hopkins) discovers that his beautiful younger wife, Jennifer (Embeth Davidtz), is having an affair, he plans her murder…the perfect murder. Among the cops arriving at the crime scene is hostage negotiator Detective Rob Nunally (Billy Burke), the only officer permitted entry to the house. Surprisingly, Crawford readily admits to shooting his wife, but Nunally is too stunned to pay close attention when he recognizes his lover, whose true identity he never knew, lying on the floor in a pool of blood. Although Jennifer was shot at point blank range, Nunally realizes she isn’t dead.

Crawford is immediately arrested and arraigned after confessing – a seemingly slamdunk case for hot shot assistant district attorney Willy Beachum (Ryan Gosling), who has one foot out the door of the District Attorney’s (David Strathairn) office on his way to a lucrative job in high-stakes corporate law.

But nothing is as simple as it seems, including this case. Will the lure of power and a love affair with a sexy, ambitious attorney (Rosamund Pike) at his new firm overpower Willy’s fierce drive to win, or worse, quash his code of ethics? In a tense duel of intellect and strategy, Crawford and Willy both learn that a “fracture” can be found in every ostensibly perfect façade.

About the Production

The genesis of a seamless thriller is never simple. Its growth from inspiration to the page to production usually follows a long, circuitous route. Fracture is no different. “Thrillers are tough,” says producer Charles Weinstock. “And when they start with a nice twist, as ours does, they’re particularly tough – because at the end of the movie, you need to top that. We didn’t want to close with some witless car chase, or a fight to the death on an abandoned pier. Throughout, we tried to construct a story that was grounded in character, which is always the solution: keep your characters honest, and sooner or later they’ll give you the next twist.”

Fracture began its lengthy gestation at Castle Rock Entertainment, where Weinstock had an overall deal in place and was working with the studio’s head of production, Liz Glotzer. For years, Weinstock had wanted to do something with writer Daniel Pyne, and when they finally met, Pyne told him he had the beginnings of an idea. “Daniel said he wanted to make a movie about a guy who represents himself in court,” Weinstock says, “but with this catch – as a writer, he didn’t want to be in the courtroom much.”

Weinstock spent another six years working on the story and eventually the project picked up speed with the addition of screenwriter Glenn Gers, director Gregory Hoblit and New Line Cinema, and together with Weinstock they continued the painstaking process of refining the story through to production.

“I was attracted by the notion that Chuck Weinstock and Greg Hoblit intended to make a ‘courtroom thriller’ in which most of the fight between the antagonists is not in the actual courtroom,” says Gers.

“The hard work for me was getting out of the perfect crime because Dan Pyne made it a little too perfect,” Gers laughs, “and we had to protect that at all costs, even while working on character development and strengthening the plot. Dan’s triangle of Crawford, Jennifer and Nunally, the clever set up, the crime, this intense puzzle that starts the story – that’s what made me want to work on the film.

As luck would have it, Gers’ sister was working as a prosecutor in the Kansas City D.A.’s office when he began working on the project. A year later, life imitated art and she took a job in the private sector at a corporate law firm. Gers took the opportunity to use his sister as a reference guide, asking procedural questions and running story ideas by her.

“It was a strange little side light into Willy’s moral quandary,” says Gers, “so I probed to learn what it was like making the transition into the private sector. But Willy is so wrapped up and enthralled with getting what he’s always wanted in terms of this new job that he doesn’t notice Crawford, so Crawford takes advantage of that weakness and sets his trap.

Director Gregory Hoblit is well known for keeping the screenwriter within arm’s reach during production, and Gers was no exception, spending months on set with the cast and crew.

“The script is the blueprint for the movie,” asserts Hoblit. “Once it gets on its feet in the hands of gifted actors, it becomes organic and takes on a life of its own. If the blueprint is good, you stick to its intentions pretty closely, making sure you hit every specific point.”

“This script is also a puzzle piece in terms of the emotional life of the characters,” Hoblit continues, “so we had to be very careful, yet still give the actors room to move. Glenn was great at understanding that. I don’t think going in he anticipated that a scene could take such a left or right turn, but he quickly realized the special things that can happen with a story with when you let the moments happen with good actors. Our blueprint was first rate.”

Hoblit read more than 100 scripts before agreeing to direct Fracture. “It was the surprises you don’t see coming,” he says when asked what made this script outshine the many others. “I knew this one was going to be fun and I knew what to do with it, how to make it,” he says succinctly.

Similar to Hoblit’s debut film, Primal Fear, the director likens Fracture to such smart murder mysteries as Jagged Edge and The Verdict, calling them “brainy popcorn thrillers.”

The characters jumped off the page into Hoblit’s consciousness, especially the scene in which Crawford and Willy first meet. Crawford has confessed to his wife’s murder, and Willy, feeling all the power of his position as an assistant district attorney, questions Crawford believing his case to be a neat slam dunk. “When I read that scene, I couldn’t wait to shoot it,” Hoblit acknowledges. “Everything else just radiated from the confrontation between them. Being able to shoot the creative dynamic of that sequence was probably the single most exciting day I’ve had in 25 years in this business.”

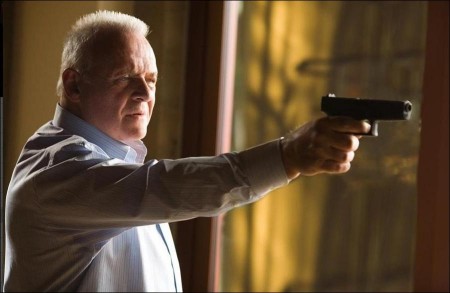

Anthony Hopkins portrays Ted Crawford, an engineer and scientist who specializes in fracture mechanics, analyzing aeronautical malfunctions and plane crashes. He prides himself on being able to spot even the smallest defect or weakness in any system, mechanical or otherwise.

It took only one read for Hopkins to sign onto the project. “It’s a smart, sophisticated, well-written script,” explains Hopkins. “You don’t get many of those today. Being asked to participate was a stroke of luck.”

But do not ask Hopkins about his character’s motivations – he’s quick to direct you elsewhere for an answer. “I’m not a film scholar, so I never analyze the ingredients of a good film. I never go into a character’s subtext,” he says. “Ask the writer for the reasons why someone does something. I just let it emerge.”

Producer Charles Weinstock laughs at the ease with which Hopkins dismisses any attempt to psychoanalyze his character. “Tony just plunges right in,” he says, describing his take on Hopkins’ acting style.

“This was one of the most enjoyable experiences I’ve had on a movie in a long time,” says Hopkins. “The part is very wittily written. Crawford is like Iago, he’s got cards hidden up his sleeve. If it’s written well, it’s easy to play.”

“I’ve played two criminals in my life,” he continues, “Hannibal Lecter and this guy. He’s a control freak. He’s fascinated by precision but that’s the very flaw in his nature. He likes to toy with people, he likes walking on the edge, and he’s a little too smart for his own good, which eventually undoes him.”

“People make a big deal about acting,” Hopkins says, “but I never treat it like a mathematical formula. The character is an engineer – OK, I’m a smart criminal; they put me in nice clothes and give me an expensive car to drive – OK, I’m a rich criminal. It’s as simple as that.”

“The character of Crawford has all kinds of colors,” Gregory Hoblit says. “From being a cold sociopath, to a charmer, to a game player, to being funny, to being deadly. There aren’t many actors who can cover that territory with ease. Anthony’s an interesting guy; he doesn’t mind going to that dark center he has tucked away, and he’s able to convey bitterness more elegantly than any actor I know.”

Given that Hopkins only appears in six or seven scenes for a total of about 25 minutes of the film, “the cumulative impact of those scenes is imperative,” explains Hoblit, emphasizing the actor’s impact. “His delivery of those scenes is what makes the movie.”

The filmmakers were determined to avoid the pitfalls of the robotic, one-dimensional antagonist. “Ted Crawford could have been a one-note, heartless bad guy,” says Hoblit.

“But Tony being Tony – a man with such depth you don’t know where it will end, or even if you want to get to the bottom of what’s lurking beneath the surface – he’s graced with such intelligence and his gifts are so formidable, you can imagine Ted Crawford is the type of man who would love to have a normal relationship, but just can’t do it. He’s blocked, and so we find Crawford jammed, with a cold, mechanical look at the world and a need to abuse. Even when he shoots his wife, as ruthless a moment as that is, you get the feeling that he’s conflicted and confused. He’s a sad character.”

Producer Charles Weinstock agrees. “Ted is wounded and because he’s so intelligent and complicated, he’s been able to dress and hide those wounds.”

“He’s the classic tragic character,” agrees screenwriter Glenn Gers. “He thinks he can step outside the law and the bounds of decent human behavior, and for a while he’s astonishingly successful at it, but then his crime haunts him and in the end he’s brought low by his own arrogance.”

“I’d written a few notes that were very ‘Hannibal Lecter,’” adds Gers. “But to his credit, Tony’s response was that he’d already done it before and wanted to make this guy different; Tony brought humanity and grace to this character which made for more than just a cold, nasty villain.”

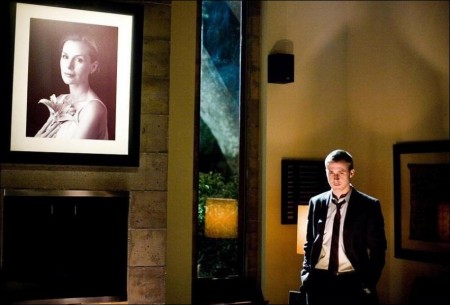

Ryan Gosling admits that an actor’s reaction to any script depends heavily on their frame of mind at the time they read it. “I was living in a tent for two months, so when I talked to Greg Hoblit from my tent, it definitely sounded interesting,” he laughs. “But I honestly wasn’t sure what I could bring to the table,” he says on a more serious note. “I just knew it was something I should do. I liked the suspense, I liked that I couldn’t figure it out when I first read it, and I liked that Anthony Hopkins was playing Crawford. It’s not every day you get to work with one of your heroes.”

Hoblit believes the stars were in perfect alignment for destiny to seemingly guide the casting process as it did. “We cast by dent of some good luck and persistence,” he says. “There is not a single role I would cast differently had we the chance to do it all over again.” Good fortune for the filmmakers because every actor felt exactly the same as Hoblit, expressly mentioning time and again their respect for him and their enthusiasm at being able to work with the director of Primal Fear.

Hoblit first noticed Gosling when he saw The Believer, which premiered at the 2001 Sundance Film Festival. “What’s perfectly clear right off the bat is that Ryan has an abundant talent,” declares Hoblit. “The kind of focus and intensity he has can’t be taught – you just have it or you don’t. That, coupled with his off-beat good looks and natural charisma, made it a pretty easy call.”

“The minute you lay eyes on the character of Willy, you know he’s a smart guy,” says Hoblit. “Ryan embodies that. His intelligence is completely apparent and because he’s such a facile actor and has so many gears, I find him compelling to watch. I honestly can’t name another actor in his age range who’s as engrossing. Shooting was endlessly interesting because nothing was ever the same from take to take because Ryan tries to find the truth in each moment. I knew he’d be a beautiful foil for Anthony.”

Gosling sees his character in a simple light. “Willy wiggles like a worm on Crawford’s hook,” he says. “He basically tortures Willy, and Willy gets caught up in something totally out of his control. There’s no relationship between them from Willy’s perspective; it’s all created by Crawford.”

“But Willy can’t lose this case because it will jeopardize both of his jobs,” continues Gosling. “Either the job he has or the one he wants to have. So losing is not really an option. And on a fundamental level, he doesn’t want to see a murderer set free, especially someone who’s enjoying outsmarting the law, and him, as much as Crawford seems to be.”

“This story is about growing up and growing a soul,” says screenwriter Glenn Gers. “Willy’s a little slick at the beginning, but he has no choice but to mature as he encounters tragedy and real loss. He’s a little careless with other people and he discovers the cost of that carelessness.”

“The movie is like a chess game,” says Gregory Hoblit. “It’s got moves and countermoves and finally a checkmate. Crawford is the chess master who’s thought out every possible move, from beginning to end, and Willy is like one of those speed players you see in Central Park, an Energizer bunny up against this stolid, methodical guy. I liked the striking difference between their physiognomies; one is grown up, and clearly, the other is not. But Willy goes from being a callow youth to being a man at the end of the day.”

The differences were not only apparent between the characters, but also between the actors and their approach to the material. The cast and director rehearsed for two weeks before start of production.

“Tony is extremely precise and economical,” describes Hoblit. “There’s no wasted motion anywhere, while Ryan’s engine wants to warm up and get going in order to find itself. He goes from being good to being quite extraordinary when everything clicks.”

Hopkins appreciated the director’s economical style of shooting using several cameras at once to get the most out of every moment, rather than making his actors shoot take after take, in effect draining the scene of its very essence and flavor. “Greg is smart and very prepared, which is always best for the production. But he also has good instincts.

We didn’t do a lot of takes, which was a relief,” says Hopkins. Acknowledged for a wicked sense of humor, Hopkins would tease the assembled crew by barking like a dog and then sit innocently as a production assistant frantically searched to quiet the errant hound.

“He really does sound like a dog,” declares Gosling. “He just one of those people who’s good at everything – he paints, he writes music, he directs and he does great imitations of cats and dogs. He’s a lot funnier than I thought he’d be, just a regular guy.”

“You’ve got to have some fun,” Hopkins says mischievously, “otherwise it’s not worth getting out of bed in the morning.”

“Tony is very collaborative,” says Charles Weinstock, “and he doesn’t exploit the anxiety that most people feel in his presence. He just isn’t interested in that.”

Weinstock reports that Hopkins has the energy and stamina “of a 20-year-old at four or five in the morning, just roaring to go.”

Billy Burke, best known for his role as Firefighter Dennis Gauquin in Ladder 49, plays Detective Rob Nunally, a married man in the midst of a torrid affair with Crawford’s wife, Jennifer.

“Nunally falls in love with the wrong woman at the wrong time,” says screenwriter Glenn Gers. “And the sad thing is, it’s real love. They’re trying to find a way out, even if it’s going to be difficult, and once Crawford mixes in, Nunally is just doomed. You really feel for him.”

“I knew going in that Nunally was going to be the hardest role to cast,” says Gregory Hoblit. “He’s a guy who goes from A to Z. Happy in love, optimistic and then in despair, and not a whole lot of scenes to get there. The role demanded a range that was considerable. I also needed to believe he was a cop who could attract a woman like Jennifer Crawford, who comes from a lofty station in life.”

“Billy had the chops to make those transitions,” Hoblit continues. “He’s handsome and believable as Jennifer’s lover, as someone who had some humanity along with the physical power, that kind of ‘don’t mess around with me’ demeanor.”

As luck would have it, Burke had recently completed a project during which he worked with professional hostage negotiators, so the actor was already up to speed when it came to his character’s profession. For Burke, the challenge was keeping up to date with his character’s moods.

“It’s rare in a movie like this, where the audience sees only bits and pieces of a character, yet that character has an entire arc, so it’s a great role, the kind I usually lose to a bigger name,” jokes Burke. “But I was licking my chops at the thought of getting this movie.”

“I don’t often find myself coming to work, trying to figure out what’s going on in the story,” he explains. “I would work for a few days, be off for a few, come back and have to get back into the plot which wasn’t always easy, so consistency was everything. Was this guy in a period of revelation? Depressed? Desperate? Resigned? It was a definite challenge, but it was also fun.”

“Billy had the most difficult part,” concedes Ryan Gosling, “but he handled it beautifully. It was a pleasure to work with him.”

Anthony Hopkins is concise and enthusiastic in his praise for his co-star, calling Burke “a wonderful actor” and “one to really watch.”

Gregory Hoblit, who has a long and respected history with the police genre in film and television, understands the chaos of a cop’s life on the street and at home. He is attracted by the dichotomy of that life and by the dangers they face each day in making life choices.

Although Hoblit was blown away by Burke’s initial audition, he wanted to be sure his performance was not a fluke and asked him to read a second time, making sure Burke could hit every emotional note of this complex character. “He was every bit as good, if not better,” reports Hoblit. ”For me, hiring Billy was a no-brainer.”

“It was the same with Rosamund Pike and Embeth Davidtz,” he says of his two leading ladies. “They were roles that you don’t know quite what to do with. At one point, there were some pretty big names being bandied about. The role of Jennifer Crawford, for example, is small, but it’s a dramatic moment that no one will forget.”

Hoblit had previously worked with Embeth Davidtz on Fallen, starring Denzel Washington, and was eager to repeat the experience. When he and casting director Deborah Aquila came up with the idea to call Davidtz at the same time, Hoblit saw it as another positive omen.

“Embeth has this fragile, butterfly quality to her,” he says. “While she is very strong underneath, she has a delicate demeanor and wonderful, emotional eyes, never mind the fact that she’s very talented. I didn’t expect her to say ‘yes,’ because the role is so small, but her response was immediate. It was gratifying. Bingo! We couldn’t have made a more perfect choice.”

One of the most difficult aspects of the film was introducing a woman who is cheating on her husband, while at the same time, getting the audience to feel for her and care about the adulterous couple.

“Embeth’s quiet grace helped in that regard,” says screenwriter Glenn Gers. “She only has two scenes to become sympathetic and then the audience needs to care about her for the rest of the story. That’s not easy.”

“Jennifer Crawford exists in a stone-cold marriage,” Hoblit says, defending Davidtz’s character. “She’s married to a sociopath, a brilliant but bloodless guy, who is an emotional abuser who shuts her off and belittles her. But this is the back story that we only discover as the movie moves forward. There is only one moment between Jennifer and her husband to convey all the dynamics of their relationship. The audience has to empathize with her and understand that this is not a person who is out having trysts in hotel rooms for fun.”

“I don’t believe for a minute that Jennifer married Ted for money,” says Gers. “She thought he would treat her well and she truly loved his strength. She wasn’t betraying him, she was changing, and he couldn’t stand that. This is not a woman who enjoys her immoral act, she’s simply afraid to leave her husband.”

“The one scene between Crawford and Jennifer took a while to write,” Gers continues, “because we had to make it shorter and shorter, strangely enough. People who have been together a long time have less to say, but each sentence has to have more weight, and Tony and Embeth knew exactly what to do with the scene.”

“She’s very beaten down,” says Embeth Davidtz about her character, “but I loved the fact that Jennifer is trying to make her way back into the world and takes matters into her own hands in a way.”

The actress was delighted to work opposite Hopkins, but the role she thought would be a walk in the park turned out to have unusual challenges. “Of course it was challenging to act opposite Anthony Hopkins, trying to match him line for line,” says Davidtz. “Because his delivery is insanely good. And acting with Billy Burke was great fun – I don’t know where he’s been hiding all these years. But the real work was lying in bed, pretending to be in a coma day after day. I thought it was going to be fabulous and easy, but I found it much harder than I expected.”

On the other side of the female spectrum is Nikki Gardner, played by British actress Rosamund Pike. The polar opposite of Jennifer Crawford, Nikki is intimidated by no one.

“Nikki is a siren,” says Gers. “She tempts Willy. She is the personification of the job that he has wanted all his life and she seduces him away from the Crawford case towards a really attractive alternative, but he has to decide if he can pay the price.”

“I don’t think Willy has ever met anyone as narcissistic as he is,” says Ryan Gosling about Pike’s character. “There’s something attractive about that initially, and they recognize a familiar ambitious quality in one another. I wouldn’t categorize Willy and Nikki as a love story; it’s more that they’re challenged by one another. They’re both alpha and the struggle to be on top is what’s more interesting than the two people in the relationship.”

“Nikki is not used to being disarmed by people,” agrees Rosamund Pike. “Willy is not what she expected. He intrigues her and frustrates her at the same time.”

Rosamund Pike first came to Gregory Hoblit’s attention when he saw a trailer for Pride and Prejudice. The actress happened to be in Los Angeles on a promotional tour for the film while making rounds at the major studios at the same time. The filmmakers were thrilled when she was able to find time in her hectic schedule to meet with them, and as soon as she left the room, Hoblit began a tireless campaign to convince production executives that although a Brit, Pike was the perfect choice for the role of the ambitious career woman, Nikki Gardner.

“Rosamund was a find,” says producer Charles Weinstock. “She has that cool blond perfection that Grace Kelly had, which served us well when her character had to be seductive and aloof. Nikki represents temptation in all its forms, romantic and professional. She’s the carnal expression of Willy’s ambition. But the role was harder than that, because Nikki also warms up, and exposes a weakness or two. Rosamund did a wonderful job of straddling those two ends of her character.”

Surprisingly, Pike found the role somewhat disconcerting. “I actually found it difficult because Nikki is someone I don’t personally agree with ethically, politically, or even stylistically. She’s one of those incredibly driven women who have chosen a career at the expense of family, relationships, a love life and anything outside her job, which is admirable in its way, but I can’t relate to her.”

“Nikki goes out on a limb for Willy,” Pike continues. “She’s let him get under her skin and goes head to head with her boss for him and humiliates herself in the process.”

“I did try to humanize her a bit,” the actress admits, “to show a glimmer of the kind of woman she used to be. I went a bit against the script to try to soften her, but when I did, Greg would ask me to drive the moment forward and give it more power and I’d think to myself, ‘well, that’s the sympathetic side gone again,’” she laughs.

Rounding out the cast is David Strathairn as Willy’s boss and persistent conscience, District Attorney Joe Lobruto; New Zealand native Cliff Curtis as Nunally’s partner, Detective Flores; and Bob Gunton as Nikki’s father, Judge Gardner.

The filmmakers were surprised but delighted that Strathairn would consider the supporting role of Joe Lobruto, especially as he accepted the part on the heels of his 2006 Oscar® nomination for Best Actor for his portrayal of Edward R. Murrow in Good Night and Good Luck.

In discussions with Hoblit, Strathairn explained that he envisioned Willy Beachum being tugged in different directions, as though from a series of bungee cords, each held by people in his life pulling from the other end. Always up for a challenge, Strathairn thought it would be interesting to be a character manipulating one of those cords.

“Lobruto is a small part,” says Glenn Gers, “but it’s a powerful one. He is the opposite of Nikki and he’s pulling Willy in the other direction. He is Willy’s conscience waiting to be found.

“David is one of my favorite actors,” says the writer, who was only too thrilled to watch Strathairn interpret his lines. “It’s wonderful to see him being celebrated at last. He brought a real decency to the part, which is what Willy needs to see when he’s dealing with the consequences of taking the wrong path.”

“Lobruto likes to think of himself as Willy’s mentor,” says Strathairn, “not just as his boss. He’s proud he made the choice to be a D.A. and not go for the big bucks at some huge firm, so there’s a flint edge between Willy and him that motivates Lobruto’s behavior.”

“Willy and Lobruto have each other all wrong,” says Ryan Gosling. “Willy thinks Lobruto is a self-righteous public servant and Lobruto thinks Willy is a sellout, a punk. Their relationship is about figuring out how right or how wrong each is about the other.”

Strathairn is another of Gosling’s acting heroes. “I love David’s work,” says Gosling. “It was an honor to work with him. He’s very inclusive in terms of his process, which was great for someone like me. He’s a gardener in real life and that describes exactly how he works; he rolls up his sleeves and really gets his hands dirty.”

“I’ve never done a role like this where you’re essentially a messenger,” says Strathairn. “There’s a lot of exposition brought to bear through the D.A.’s office about the case, about Willy and his journey. The challenge is in adding to the mix and not being a boring, utilitarian information center.”

Cliff Curtis portrays Rafael Flores, the detective on duty fated to catch the Crawford attempted-homicide case. Unfortunately for Willy, the only people Flores dislikes more than criminals are lawyers. Known for his role in Whale Rider, Curtis is used to playing a wide variety of ethnicities and nationalities. A chameleon, Curtis is quickly becoming a master at different regional accents. His dedication to acting and his curiosity to learn more about his character enticed the filmmakers to expand the role.

“Cliff is electrifying,” says Gregory Hoblit. “His presence and personality are unusual, and he has this deadpan way about him, but because his accent is pretty distinct, we had to really work on that. He didn’t really have a frame of reference in terms of being a cop, so he was ferocious about getting it right. No actor was as intent about the process.”

By all rights, Detective Flores and Willy Beachum should be comrades in arms, strategizing to put the criminal behind bars, but they soon find themselves in a stalemate, frustrated at the lack of hard evidence for what should be a clear-cut conviction.

“Flores and Willy are completely different personalities,” explains Ryan Gosling. “They’re from different backgrounds with different life perspectives but they have to work together on this case. They kind of blame each other for the situation they’re in.”

Another small but important role is that of Nikki’s father, Judge Gardner. Hoblit remembered Bob Gunton from his performance as the warden in The Shawshank Redemption and knew that casting director Deborah Aquila was old friends with the actor. “Bob is stolid,” describes Hoblit. “We needed someone who was credible and like Jennifer Crawford, memorable. When Deb brought up Bob, it was an easy choice.”

Since his days working with Steven Bochco on “Hill Street Blues,” Hoblit has strived for verisimilitude when it comes to telling stories about the law. “I want to make it right,” he says plainly. “I want to get all the cop stuff right, the courtroom drama, the law. Over the years audiences have become sophisticated and they know if you are playing fast and loose with them, or not.”

Obviously laws are different in every state, but the filmmakers took great pains to be authentic in their depiction of the action. Not only is Hoblit experienced in crime drama, producer Chuck Weinstock is himself a “lapsed attorney” who worked as a lawyer under Mayor Koch and Mayor Dinkins in New York City. The filmmakers also relied on the services of attorney Bob Breech, who previously worked for Hoblit on the popular series, “Hill Street Blues” and “L.A. Law.” According to Hoblit, Breech has “great story sense.”

“Bob knows the law inside and out,” says Hoblit, “and he understands how to get the best out of a scene dramatically while attending to all the legal aspects at play.”

“The politics, the etiquette of the courtroom, it’s all very complicated,” says Ryan Gosling. “Bob was a big help.”

The filmmakers also took advantage of technical advisor Peter Weireter, a chief hostage negotiator with the Los Angeles Police Department, and his colleague Sgt. Lou Reyes, who helped with several of the opening scenes. While the filmmakers did take some license, Hoblit is quick to point out that bending some rules can work, but only if filmmakers take care not to go so far as to do a disservice to the profession being depicted on screen, which in the end, does an even greater disservice to the script.

A major focal point in the film is the Rube Goldberg-like machines, big and small, which adorn Ted Crawford’s home and office. These brass and wood pieces serve as dramatic metaphors for the story as well as for the intricate workings of the sociopath’s diabolical mind.

Writer Glenn Gers came upon the idea of using a rolling ball machine in the story while playing with his five-year-old son who likes marble mazes. The marbles roll through a labyrinth of confusing tracks only to come out in unexpected places.

According to several versions of Webster’s dictionary, a Rube Goldberg machine is a device that “accomplishes by complex means what seemingly could be done simply;” or something “having a fantastically complicated, improvised appearance.”

“These toys, along with the stunning piece of machinery that’s Crawford’s GT Porsche, even his house, they are all reflections of his personality and his inner wiring,” agrees Gregory Hoblit, likening Crawford to a surgeon or Swiss watch maker.

On the written page, the mention of a Rube Goldberg-like device requires the reader to call upon a vivid imagination, but it is an entirely more complicated endeavor to recreate such an apparatus for practical use. No computerized visual effects here.

“It’s always best when you can find an external sign to show the inner person,” says Gers, “but when I wrote the paragraph, I never really imagined the complex machine they would have to build. When I saw it on stage, I kept apologizing to the guys who had to build it,” he laughs.

Producer Charles Weinstock and production designer Paul Eads began the search for any kind of gadget that might fill the bill by scouring the Internet. To their amazement, they discovered a variety of clubs and rabid fans all over the world whose hobby it is to design and build their own adaptations on Goldberg’s theme.

After long examination and discussion, the filmmakers settled on using Dutch artist Mark Bishoff’s sculptures as Crawford’s work. It had taken Bischoff, a music teacher, over ten years of loving labor to complete his intricate rolling ball machine.

“His work was stupefying,” says Hoblit. “To think he worked after giving cello lessons all day to create the caliber of piece he did, with the size of the tracks, the quality of the wood, the complexity of the pieces, all of us sat in my office, looking at his video, oohing and aahing. But then the question became ‘how are we going to get something that big out of his basement and across the Atlantic?’”

“We asked him to send us some samples of the rings, the balls, anything to use as a template,” recalls Weinstock. “He acted as a consultant through the manufacturing and assembly process. Whenever we had questions, he was there to help.”

The filmmakers and Bischoff reached an agreement in which Bischoff would furnish the movie with his designs in order to construct a smaller version of his much-admired piece. The artist even sent the production a small table-top piece to borrow for the shoot.

Executive producer Hawk Koch hired special effects coordinator Larz Anderson to build several configurations of Bischoff’s designs. Anderson and his team were honored and excited to step outside the normal realm of their duties of pyrotechnics, explosives and mechanical effects to build the 8-foot sculpture along with a same-size “stunt double” version. Together with Eads they designed the kinetic brass sculpture and its wooden base to compliment the dynamic architecture of Crawford’s unique house.

The large sculpture measures 8 feet high x 8 feet wide x 2 feet deep and uses two 12-volt electrical motors operated via remote control. The manual desktop version is about 14 inches x 32 inches x 12 inches wide.

“Working on this project was like being a kid again,” reports Anderson. “Everyone wanted to contribute their ideas. It’s not often you get asked to build a giant puzzle. It wasn’t an easy piece to move, especially once it was assembled, because it weighs about 250 pounds. But the hardest part was keeping people from touching it and playing with it or taking the balls once it was on set.”

But no one could keep Hoblit, his cast and crew from spending long breaks between set ups, staring at the rolling balls as they made their way through the intricate maze.

“Greg would stand in front of any of those machines, start watching and that was it,” jokes executive producer Hawk Koch. “I’d say, ‘Come on, Greg, we have to work,’ but he couldn’t move. The machine has its own kind of rhythm; it lulls you into a meditative state. It’s pretty amazing.”

Hoblit imagined a giant erector set when he first read Gers’ description in the new script, but even he was unprepared for the beauty and immenseness of Anderson’s creation.

Hoblit admits that he decided to “swing for the fences” in making Fracture. In the hope of not “playing it too safe,” he attempted a pace and tone more “daring” than his previous work. In doing so, he has tried creating a contemporary film noir.

“For me it was unexpected,” Hoblit says of tackling a darker, more mysterious style. “As the script evolved my ideas became more pronounced, but I was not interested in doing something strictly noir. I wanted something sleek, to use refracted light, and I wanted to be specific in my use of color.”

Hoblit referenced the work of various photographers he’s admired throughout the years. An avid fan of Bruce Davidson, whose book Subway made a huge impact on the director, Hoblit pays homage to Davidson’s muted backgrounds, the neutral faces of his subjects and the unusual, iconic pops of color he uses in each frame.

When Hoblit began his search for a director of photography, it was imperative to find someone who could think outside the box, but not too far outside so that Hoblit would have to spend valuable time reining the cinematographer back in line. After discussing his ideas with some colleagues he found a daring new talent in Kramer Morgenthau, who had made a mark in commercials and low-budget films. Hoblit also saw a level of frustration in Morgenthau that could work to the film’s advantage.

“His juxtaposition of colors was great,” Hoblit says of Morgenthau’s work, “I had never seen anything quite that bold. And I liked the fact that he was eager to move out of the box he’d found himself in, which happens in our business. But he’s off and running now,” Hoblit says proudly.

“In terms of the look, Fracture is a story about class,” says Morgenthau. “Willy’s world is gritty, in the trenches, more like the D.A.’s office and even the courtroom to a certain extent. Crawford exists in a world of wealth and big, beautiful spaces. So we talked a lot about color versus a gray scale to create a contrast between the two.”

Once Morgenthau and Hoblit met with production designer Paul Eads, set decorator Nancy Nye and costume designer Elisabetta Beraldo, they developed the film’s overall look.

There are a preponderance of low-lit scenes and a good deal of night work both interior and exterior that the filmmakers would light with different hues of color to set the tone of each scene.

“The movie is fairly dark,” Hoblit explains, “but we also used vivid greens, oranges, reds and yellows. I wouldn’t say that there’s a color palette so much as there is a vibrancy of color always cutting through the darkness so that it’s unexpected and we don’t know where the color is coming from. Kramer and I were always negotiating with ourselves to make sure we didn’t tip over the edge into self-indulgence or idiocy,” he jokes.

“Greg is first and foremost about the story,” says Morgenthau. “He wants it to be truthful and logical. I think that’s why he’s been so successful. He doesn’t take anything for granted and feels as though it’s an insult to the audience to cheat or not have the environment or action as it would be in real life; that’s become a stylistic trait of his. Yet, at the same time, he’ll take the lighting to an expressionistic level, which is also my approach.”

Hoblit credits his producing partner Hawk Koch with the ease of the shoot. “Hawk puts together a brilliant game plan for getting a movie done,” the director says.

It was important to the filmmakers to shoot in Los Angeles for a variety of reasons, not only because of proximity to home, but also with the desire to help keep production in Hollywood. Despite a pack of naysayers at his heels, Koch was able to create a costeffective budget without sacrificing quality.

“My challenge was to make our film look like a 60 or 70-million dollar film and not spend anywhere near that kind of money,” says Koch. “I’m proud that we could make a richlooking movie, work decent hours and do it for a good price. We owe thanks to our D.P., Kramer Morgenthau, who can light fast and made every scene look exquisite. He’s going to have a name as one of the best in the business for a long time to come.”

Hoblit likes to make movies that look as though they are set in Anywhere, USA so that audiences can more easily identify with the characters. He credits production designer Paul Eads and location managers Richard Davis and Mike Fantasia with helping to make that happen.

Despite the fact that southern California is home for most of the production team, shooting Fracture in Los Angeles presented many surprises and offered Hoblit and his crew a new look at the city.

“L.A. is an amazing place once you get past the bias about its being flat, sprawling and architecturally uninteresting,” jokes Hoblit. “L.A. is usually shot in harsh light, very washed out, but I loved giving it a three-dimensional, rich quality, even in some of the more rundown sections of town. It has so much color and personality.”

“It’s a bit of a forgotten city for the moment,” says Ryan Gosling. “It’s rundown, but there’s some amazing architecture and beautiful buildings that have been ignored since they were built at the turn of the century. But it’s beginning to be renovated and regentrified, so it’s an interesting time to be down there because it’s still a bit of a ghost town and it will never be like this again.”

Gosling was particularly thrilled to shoot at Disney Hall because, try as he might to find tickets to the any of the sold-out performances since the hall’s opening, he came up empty-handed. “I was so irritated because I could never get tickets,” he says in mock despair, “but not only did I get in this time, I got to walk on stage, explore backstage, sit in the best seats, see the view from the roof,” he laughs. “I got a really unique tour, so I feel pretty lucky.”

Fracture was the first motion picture to utilize the main stage and auditorium of the Frank Gehry-designed performing arts center, where the company filmed mezzo soprano Vivica Genaux and her accompanist, Paul Floyd. They also shot several pieces of the sequence where Willy and Nikki first meet in the foyer area.

The Crawford home was another architectural wonder located in the Encino area of the San Fernando Valley, where the company spent several weeks shooting at a private estate. “The house sits behind these big gates like a cement and glass bunker with a buttressing overhang,” recalls Hoblit. “It must be 80% glass, supported by struts, but you can see from one end of the house all the way to the other, all the way through it, side to side, end to end, anywhere you go. It would be a little unnerving to live in a house like that, but fortunately it’s pretty well-hidden.”

The Sherman estate is protected on all sides by giant hedges, walls, gates, and a formidable hill that leads to a guest house and tennis court which perch high above the pool and backyard. It is also surrounded by a small orchard of orange trees, rose bushes, lavender and blooming flora. It has been used in films before, but has never been showcased to this extent.

Hoblit and Morgenthau particularly liked the reflections and double images that occurred when shooting through the house and its many layers of glass, a circumstance usually considered a mistake in traditional camera work. They frequently placed their cameras outside the house to film scenes going on inside, another rare occurrence for Hoblit, who calls himself a “stickler” when it comes to being close to the action, but in this case took advantage of his ability to use his cameras as the eyes of a voyeur.

Hoblit calls the house “camera-friendly” and says “it was just made to order; a real gift,” while Morgenthau believes the opposite, but attests to how good the house looks on camera.

“It was very film-unfriendly, but it was worth every bit of effort and heartbreak and stepping on top of each other,” the cinematographer says. “It was a classic, Schindlerinfluenced building, where the interiors and exteriors flowed from one to the other, but it was not easy,” he laughs.

Other locations used include the prestigious law firm, Jones Day, The Standard Hotel Downtown LA rooftop bar, Los Angeles City Hall and the now-vacant women’s prison, Sybil Brand Institute. The company also spent time at a private residence in Hancock Park, at RFK Medical Center in Hawthorne, in Santa Monica at the Fairmont Miramar Hotel and at Steelcase Furniture Showroom and Sales Office, and in Long Beach at St. Mary’s Hospital and West Coast Aircraft Charters, among others sites.

Hoblit hopes Fracture entices the same audiences who loved Primal Fear. “I think the film has wide appeal,” he says. “It’s entertaining, it’s got a brain, and it showcases a lot of wonderful actors who will probably expand their fan bases because it’s a different look into what they can do.”

Anthony Hopkins agrees. “It’s a well-made movie of the old school,” he says. “You want to know if Willy’s going to nail Crawford, but you’re more fascinated by the process of getting there.”

And even though executive producer Hawk Koch knows the ending, he vows, “I still can’t wait to sit in the theatre with my popcorn, watch the movie and just escape for a couple of hours. Hopefully audiences will agree.”

Production notes provided by New Line Cinema.

Fracture

Starring: Anthony Hopkins, Ryan Gosling, David Strathairn, Billy Burke, Rosamund Pike, Valerie Dillman

Directed by: Gregory Hoblit

Screenplay by: Glenn Gers, Daniel Pyne

Release Date: April 20th, 2007

Running Time: 113 minutes

MPAA Rating: R for language and some violent content.

Studio: New Line Cinema

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $39,015,018 (42.9%)

Foreign: $51,919,718 (57.1%)

Total: $90,934,736 (Worldwide)