Tagline: Welcome to the suck.

“Like most good and great Marines, I hated the Corps. I hated being a Marine because more than all of the things in the world I wanted to be-smart, famous, sexy, oversexed, drunk, f***ed, high, alone, famous, smart, known, understood, loved, forgiven, oversexed, drunk, high, smart, sexy-more than all of these, I was a Marine. A jarhead.” Anthony Swofford, Jarhead.

In the summer of 1990, Anthony Swofford, a 20-year-old third-generation enlistee, got sent to the deserts of Saudi Arabia to fight in the first Gulf War.

In 2003, his memories of that time in that place became the best-selling book Jarhead. Swofford wrote with the urgency, immediacy, honesty and humor that could only come from someone who had lived through the experience itself.

Swofford’s book spent nine weeks on The New York Times list of best sellers and was hailed in that same publication as “some kind of classic…a bracing memoir of the 1991 Persian Gulf War that will go down with the best books ever written about military life. A wild passage familiar to millions of young men but rarely so well revealed.”

The Times’ Michiko Kakutani noted that Jarhead was “an irreverent but meditative voice that captures both the juiced-up machismo of jarhead culture and the existential loneliness of combat. He makes us understand the exacting and deadly art practiced by a sniper…the rhythm of boredom and terror of preparing for an enemy attack and the terrible physical and psychological costs of combat and the emotional bonds shared by the soldiers.”

Here was the unvarnished story straight from the mouth of the then 20-year-old kid, who told of a very different war from the one delivered in print or over the air. Here was the war from the ground up with images of burning oil wells shooting flames into the night sky, like comets that had fallen to the earth; rowdy, horny, dusty recruits, exhilarated and also terrified that at any moment, over the next hill, the war might begin; young men, suddenly dropped down in an unforgiving terrain, seeking diversion in a game of gas mask football, awaiting care packages of letters and porn, betting on staged scorpion fights and getting blind drunk to celebrate a Christmas away from their families. But out of this hellish situation ultimately arose unlikely friendships, fierce loyalty and do-or-die camaraderie-a brotherhood of jarheads sworn to be always faithful…semper fi.

Mendes and the filmmaking team now collaborate on the next generation of war movies with Jarhead, an unforgettable view of war as seen through the eyes of one Marine-as if J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield had been deployed to the Gulf.

Recruiting the Filmmakers

“When I first read the book, what I responded to was the fact that the war was viewed through the prism of a very specific kind of person: one who was trying to deal with and discover who he was. I was enthralled by the mixture of machismo, comedy, surrealism and wry observation,” director Sam Mendes recalls about first reading the Gulf War memoir Jarhead. “It was a war book like no other, about a war like no other, that might possibly be a war movie like no other.

“Every Marine has a different experience, every platoon has a different experience, every battalion has a different experience-even of the same war. I was interested in making a movie about this particular fascinating individual and how his experiences in this war shaped him.

“What we remember about the Gulf War,” continues Mendes, “were these clean little images of these tiny little bombs perfectly hitting these toy towns, bereft of any sense of human life at all. A soldier on the ground has absolutely no idea of what’s going on. To me, the interesting thing now is to enter it through a person on the ground, because that’s where we weren’t allowed to go in this particular war. Tony’s experience in the desert took what we consider normal about war, on its head-as if Salinger were dealing with the Gulf War.”

Swofford’s best-selling and critically acclaimed book about life as a Marine in the early 1990s had been praised for many things, notably the painful honesty and irreverence with which the narrator viewed his world-a first-person observation from a third-generation soldier (Swofford was conceived in 1969 when his father was on leave from Vietnam) of the war machinery that surrounded him. In place of the classic imagery of scrubbed, uniformed heroes dedicated to a cause were young recruits in sweaty desert gear with a passion for rock music, a predilection for pornography and a growing and unfulfilled bloodlust.

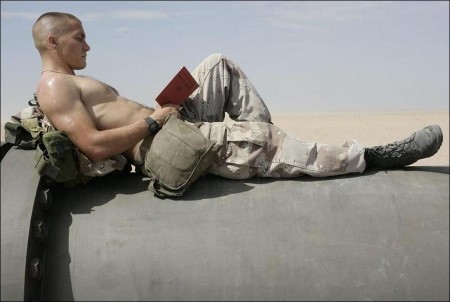

Having been trained for the kill and then stationed in a barren, inhospitable, surreal landscape, the testosterone-charged crucible produced alpha-male infighting (since there was no enemy in sight), debauched behavior and general disrespect for everyone from their commanding officers to the people they were sent to liberate… and all of it narrated by a soldier who is, at first, more at home reading Camus than adjusting to the harsh realities of jarhead life.

“If I was going to tell any story about the Gulf War, the one that I needed to tell was my own,” says Swofford. “I was 18-years-old when I joined the Marine Corps in December of 1988. The Marine Corps itself is very seductive for certain young men. Once I was in the infantry, I saw a group of guys who carried better rifles and had better gear. I found out they were the snipers, and there was a mystique about them.”

Swofford was then given the opportunity to advance from being a “grunt” to becoming a scout/sniper in the elite STA (Surveillance and Target Acquisition) Platoon. “The grunt fights for 15,000 poorly placed rounds; the sniper dies for that one perfect shot-I was hooked.”

Producing partners Lucy Fisher and Doug Wick, who purchased the book just as it was hitting the streets, believed in the timelessness of the material and the singularity of the author’s painful, funny and observant voice. Their faith was confirmed by screenwriter William Broyles’ own experiences as a Marine in Vietnam.

With a son in the military, Broyles identified with Swofford’s story, as both a father to a young soldier and someone who’d seen combat first-hand. He says, “Tony’s generation had a more clear sense of purpose. For whatever reason, they all wanted to be there. We were drafted. And by the time I got there in 1969, we had no idea what we were there for.”

“When I first spoke with Bill about adapting the book, he started explaining to me, from his own experiences of serving in Vietnam, that it’s a club you never leave,” says producer Doug Wick. “I was kind of surprised to hear this sophisticated writer-whose time in the service was nearly four decades ago-talk about how he was a Marine forever, how those guys who knew each other so briefly, so long ago, felt linked forever. It struck me that this was a story worth telling.”

Broyles adds, “When I got back from Vietnam, I missed having my weapon. There’s some kind of primal connection you have with your rifle-it’s like a cowboy and his horse. You take the cowboy off his horse and he still walks bowlegged because they are one thing, just like you and your rifle.”

As told by Swofford and echoed by Broyles, soldiers in wartime experience something outside of the realm of understanding of most civilians-that adrenalized high that comes from the relentless intensity of everything the soldier does, from the seeming monotony of training and drills to the actual time in battle. For them, the viewing of such now classic films as Apocalypse Now, Platoon and Full Metal Jacket works as an aphrodisiac, whetting their appetites for the coming conflict and celebrating the beauty of their fighting skills. These themes, combined with Swoff’s own unique story of growing up in this hothouse environment, would make a screen adaptation a tricky feat to pull off.

Lucy Fisher comments, “The book is unique in both style and content, and we knew it would require some extraordinary talents to make it cinematic. It’s a very literary work, a coming-of-age story in the midst of chaos that’s alternately funny and terrifying. Once Bill had a first draft screenplay, we set our sights on the one director we believed had the vision to put it all together: Sam Mendes. We wanted somebody with the intelligence to deal with the actual seriousness of the topic and yet know how to make it funny-Sam does that brilliantly.”

Wick adds, “American Beauty was `Sam Mendes Goes to the Suburbs.’ Jarhead, which has some of that same sensibility, is a little bit `American Beauty Goes to War.’”

Fisher picks up, “Sam is such as stylist and such a humanist that the fact we saw so little of the human side of this war was a unique creative opportunity for him. What was unusual from the public’s perspective is that so few images from this war were ever shown on television, in newspapers or in magazines. So, this movie will contain imagery that you will never have seen in any other way.”

“I think you need time, you need hindsight, to begin to understand what you have lived through, particularly if you’re going through something as seismic as a war,” observes Mendes. “As often happens with huge historical events, you need a bit of distance to fully understand them. The Gulf War is certainly a different event now from what it appeared to be then.”

As viewed through the lens of mass media at the time, Operation Desert Storm seemed like the perfect war-if one can apply such an oxymoron. And as such, it proved to be a brand new experience, even for the most seasoned soldier.

Mendes offers, “It’s fascinating to me that it took ten or twelve years before a lot of the guys wrote memoirs about this first Gulf War. You’ve got to ask yourself, `Why were there so few in the immediate aftermath of the war? Why did it take this much time?’ And I think the answer is that what seemed to them at the time almost a non-war now, in retrospective, seems much more interesting. I think we realize now what it was part of, historically speaking. The intensity of that experience has a huge amount to tell us about what’s going on now.”

Mendes and Broyles worked on many drafts of the script, pulling Swofford’s story out of the non-linear episodes chronicled in the memoir and concentrating on his time while in training and in the desert. (Swofford was deployed on August 14, 1990, just two days after his twentieth birthday. His battalion, the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Marines, was one of the first units to reach the Gulf and was instantly dispersed into the desert. They immediately dug in and waited for the fighting to begin…)

Mendes explains, “Immediately after a war is finished you get the factual accounts, the details. What we’ve tried to do is take the feelings, the impressions, the subjective version of events to create a different account of this war.”

Broyles adds, “Our story is unromantic and apolitical. It’s about young men who join the Marine Corps trying to find a place for themselves in life.”

Enlisting the Platoon

“I’d read the book on a plane and came away really moved by it-it was purely emotional and without any of the clichés of other war stories,” says Jake Gyllenhaal. “When I got the script, I was told by Sam [Mendes] that Bill [the screenwriter] had served in Vietnam and, to be honest, I had some concerns about that.

“To me, Vietnam was a different generation, a war that everyone of that generation was involved with in one way or another. I was 11 when the Gulf War started. There is a kind of weird distance from it. We don’t have the same experience of it that the Vietnam generation had of that war.”

Gyllenhaal’s concerns were alleviated once he read Broyles’ adaptation of Swofford’s memoir. He was instantly eager to take on the challenge of portraying the author-but found he would have to wait a bit.

After his first reading for Mendes, Gyllenhaal got the ominous feeling that he didn’t nail the audition. After a few months had passed and the actor heard that the director was meeting with other actors, Jake left an impassioned message on Mendes’ voicemail (“I’ll do whatever you want me to do, but I’m the guy to be in this movie!”). A month later, the director informed him he had the part.

In addition to downplaying his chances of securing the role, Gyllenhaal underestimated the physical-and mental-transformation the role would bring about.

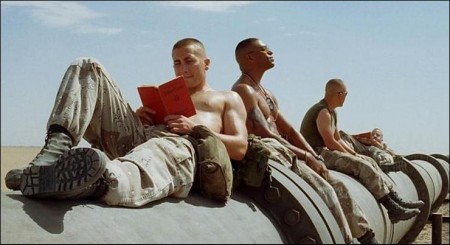

“When the other guys and I first got our jarhead haircuts, I was really into it-and then, as soon as it happened, it was odd to me,” Gyllenhaal recalls. “But I think that feeling was appropriate. I think that Swoff likes to stay apart from the group. He’s an observer as well as a team player, and Sam created an atmosphere in which I could observe and be a part of a group simultaneously. I always felt an interesting juxtaposition of feeling like I was an integral part of the platoon while simultaneously feeling apart from it. I think that was Sam’s intention.”

Peter Sarsgaard-who plays Troy, Swoff’s friend and spotter / partner in the STA-offers, “The main reason I wanted to do this film was because I felt like it acknowledged the hardships of what it means to be in a war. We just got a little touch of it through being in this movie. I mean, in the end, we’re just actors.

“What was the most difficult for us were the elements, mostly. We were either freezing our asses off-being soaked in the rain for 12 hours or out at night in the desert-or we were frying-working in the sun in full combat gear or making our way through a sandstorm. But it’s a little obnoxious to complain about things like that when there were guys over there who did just that for months and had to face live ammo.”

Another aspect of military life for the first Gulf War soldiers-and all soldiers who served prior to the gender integration of the armed forces-that presented a period of adjustment for new actor/enlistees was the absence of women in their midst.

“I’ve gone through real bonding experiences working with groups of actors, but there’s something about being around a large group that’s almost exclusively male that’s totally unique,” Sarsgaard explains. “I mean, there’s the script supervisor and a camera loader, and maybe only one or two other women on the crew. Even the hair and makeup people were nearly all men.

“Frankly, I think we all got sick of it,” he laughs. “Male banter gets really raunchy, and you get a little tired of it. There’s something about the banter that’s tied in with the violence, and it’s usually always centered around sex. Sex and violence-there you have it. Factions form, too. I think of all the movie sets I’ve been on, this one has had more bickering-and more love-than any other.”

Staying appropriately out of the grunt grappling was platoon leader Jamie Foxx.

“I think it’s very appropriate that Jamie Foxx plays our staff sergeant,” says Gyllenhaal. “Everyone respects him as an actor. He keeps himself apart from the guys, quietly playing chess between scenes. We all play him, and he always wins. There’s a pecking order in the Marine Corps just like there is on a movie set. And it’s just so easy to look to Jamie as our leader. I instinctively and naturally look up to him.”

Foxx comments, “One of the first things Sam told us was, `Read the book, but don’t take it to heart, because the movie is going to be something different.’ The book was just one man’s thinking of how he was affected by the war. The movie lets you see everybody’s side of the thing. My side is with the Marines.”

Prior to filming, Foxx also spoke with a friend who happens to be a Marine: “He’s African American, so he’s always had to work harder and be sharper. But he said once you become a Marine, that’s your family. There’s no color except the color of your uniform. You’d never survive without the camaraderie.”

Another Academy Award winner, Chris Cooper, was charged with bringing the zealous, smart and charismatic Lieutenant Colonel Kazinski to life. Kazinski wields his leadership skills like a sideshow barker or Vegas M.C.-he is a motivator who knows how to whip up a crowd. But beneath the huckstering is a shrewd soldier with battle scars and medals to back up his rank.

“In a life-threatening situation, a group of young men are looking toward someone for leadership. They can tell when they’re being fed a line,” shares Cooper. “Kazinski is a motivator who gets how to energize a crowd, and he understands that a good commanding officer must wear many different hats. He knows when it’s time to be a best friend, when to be a father figure and when to drive his men into the ground. Because this soldier is responsible for the lives of his troops, he believes he must have the smarts and the skills to back up his zeal. It was this dynamic that made Kazinski an interesting character to me.”

Foxx’s Staff Sergeant Sykes represents the lifer, the type of soldier whose unshakeable belief in the Corps way of life is all consuming-the compass by which he steers his course; Cooper’s Kazinski, the same. For the Marines under their command, however, life has many more shades of gray than the black and white way of life lived by their leaders. For them, the party line is a lot harder to swallow.

Lucas Black plays Chris Kruger, company rebel, who seems to be one of the only ones in the troop with any concern of the politics that got them into the war.

“My character likes to joke around, and he tries to get on some people’s nerves by asking a lot of questions,” says Black. “He knows a lot about what’s going on, and he likes to put questions in people’s minds-why are we here and what are we doing here?” Kruger’s questioning nature is made evident in a scene where the platoon is issued additional pills to protect them from potential chemical and biological weapon attacks-issued as back-up to their NBC (nuclear / biological / chemical weapons) suits. After ascertaining that the military has yet to test the experimental drugs, Kruger is the only one in his unit who does not swallow the meds.

The other soldiers in Swofford’s unit run the gamut from rebel to rank-and-file: Evan Jones, as the loudmouthed, cocky Fowler; the shy social misfit Fergus O’Donnell, played by Brian Geraghty; Jacob Vargas’ committed fighter Cortez; and the imposing Cuban American Escobar, played by Laz Alonso.

It was Mendes’ intention that all the actors experience as much of Marine life as possible. With the reality of time constraints and filming schedule, however, the director knew that the best he could hope for was a somewhat superficial transmutation. Yet he was determined to at least give the actors a taste of the “real thing.”

Prior to the start of principal photography (which itself was preceded by a thorough three-week rehearsal), the platoon of 13 actors/soldiers attended a four-day boot camp at George Air Force Base, led by military advisor Sergeant Major James Dever (who has assisted large-scale filmed military operations in projects such as The Last Samurai and We Were Soldiers).

“We lived in tents-the exact kind of tents that they would be using in their camps out in the desert-and we slept on cots,” Dever explains. “And we made sure the training they received was the same as what the Marines receive before going to the desert. It was basic Marine Corps training, albeit sped up. The actors were very motivated.

“We issued equipment to them the first day. We showed them how to put on their combat gear, where to put the canteens, the magazine pouches, things like that so they would understand the equipment. No walking-they had to run everywhere. We went on forced marches carrying full packs. Every morning we went through physical exercises and drills. We gave classes at night on the NBC suits and protective masks. They worked hard, but there was no complaining. And everything was very quick.”

“I wanted them to have some idea of what it felt like,” says Mendes. “But it was nothing compared to what Marines go through. I’m one of those people who gets bored of hearing actors say, `We went to boot camp, and we know what it feels like to be Marines.’ They have no idea what it feels like to be Marines, and neither do I. What I wanted them to have was a physical knowledge of certain things so they could accurately portray Marines.

“Did I push them physically beyond the point that I normally would with an actor?” he continues. “Yes, absolutely, because they’re acting physically. They’re experiencing the pain, the exhaustion, the heat. I wasn’t going to push them to the point where I had collapsed actors on my hands, but I wanted them to go a little further than they would go normally.”

Mendes notes that the combination of the subject matter, the setting, the testosterone and commitment made for an intense experience for everyone involved: “I feel like there’s something that went on between all the actors in this production that they’ll carry with them back into their private lives. I think they were affected deeply by the depersonalizing influence of being in the military. I think there’s a certain type of human being that seeks that-to be part of a team, to be part of something bigger than themselves, to lose themselves in something with a grand objective.

“But I think you’ll find that they are opposite to the types who want to be an actor,” he continues. “I think the friction between those two has led to a lot of what has gone on on-set. It’s made each performance a struggle for individuality within the context of a group. I wanted to take the actors by surprise-I wanted it to be a journey of discovery for them. Coming from the theatre, the process, the journey is its own end result. And I think here, this journey has been a fascinating experiment-for all of us.”

Mendes concludes, “I think it’s very difficult for most human beings to sublimate where they stand in the world, put that on hold and just be a body-because at the end of the day, that’s all you are when you’re in a war situation. There’s a reason why everyone looks the same, because fundamentally, they are the same. You have to be well trained to spot any insignia anywhere on a Marine uniform: no names, nothing. Everyone looks the same. It’s deep in the psychology of the Marine Corps. It’s beyond my comprehension on some level. But it’s also something I hugely admire and respect because it’s very, very selfless.”

Welcome to the Production

Location shooting in the original setting where Swofford found himself in 1990 was never an option, so filmmakers searched for venues to stand in for a variety of locales where the main action of Jarhead takes place.

Filming began on the soundstages of Universal Studios; principal photography would end almost exactly five months later in the desert of Glamis, California.

“One of the great ironies of the movie,” notes Mendes, “was that the filming of it lasted five months…which is exactly the length of time the soldiers in Tony’s story were in the desert together.”

The first location work took place on George Air Force Base in Victorville, California. Closed during the BRAC (Base Reassignment and Closure) movement of the early 1990s, the sprawling facility still houses military operations and is temporary residence for personnel in transit to more permanent assignments.

One of the scenes shot there depicts troops loading into planes for the flight to the Gulf. On the morning of the filming, real military planes carrying U.S. troops landed near the 747 being boarded by Jarhead’s simulated soldiers. There was some mingling between the movie extras and military personnel, each curious about the business that the other would imminently embark upon-along with an acknowledgement that only one 747 would be leaving the tarmac. The chance encounter allowed everyone involved an opportunity to try on a new perspective-if only for a moment-and view his own job from another point of view. Most involved in the production came away with a new appreciation of the world to which they were returning at the end of the day’s shoot.

George Air Force Base is currently owned by the city of Victorville, which is working in concert with a group of developers to transform it into a mixed-used facility offering private housing and shopping. Though it is still being used for some training and transport, the U.S. military no longer has a say over who utilizes the property. The Jarhead production was a welcomed visitor.

In any re-creating historical event-rather one person’s perspective of the time-film production runs the risk of either constructing a museum piece or modifying the story and / or setting to fit with current attitudes and mores. Neither choice was acceptable to the Jarhead filmmakers and cast, who were committed to filmically depicting Swofford’s personal experiences.

One of the unique challenges for the production team was in the re-creation of scenes showing military action. The Gulf War was uniquely apparatus-driven (none of which would be provided to the movie by a cooperating military), and despite the perception that it had been “covered” by the media, it was a war in which few were familiar with the actual details of what occurred on the ground and one that failed to impart any strong imagery.

“With any work that tries to be accurate in its depictions, there’s the risk of getting every detail right and yet missing the spirit,” says Wick. “We took great care in the details. We had military experts like Sergeant Major James Dever, one of the world’s best production designers in Dennis Gassner and one of the top costume designers in Albert Wolsky. But ultimately, the goal was to re-create the spirit.”

The director says, “These Marines were put through very extreme experiences in 1990. They were subjected to intense training and then shipped off to this moonscape that is the desert-which had the effect of making them feel absolutely and utterly out of touch with the world but, perhaps, more in touch with themselves. And the movie is filled with moments in which they act out what they think the war might be, or how they should be when it starts, or what they might do and what they might say. But the reality is that it’s unlike anything they ever expected. They have a boy’s idea of what war is. The one thing I can guarantee you-even though I’ve never been to war-is no war is exactly what people expect. It is either faster or slower, more violent or less violent. It creeps up on you in the middle of the night or it smacks you in the face at the point when you least expect it. And Tony’s story shows us that.”

The company moved from Victorville to Holtville Air Strip east of the town of El Centro, California, in Imperial County, the southernmost county in the state of California. Little is known about this airfield, including its real name, purpose or date of construction. Despite its 2,400-foot length of asphalt runway, USGS (United States Geographical Survey) topographical maps from 1969-1992 never indicated the presence of an airfield at this location; the only archival evidence of its existence is a single aerial photo from 2002. Its proximity to the Chocolate Mountains Naval Aerial Gunnery Range suggests it may have been constructed as a target airfield or as an “expeditionary” airfield for training use by AV-8 Harriers from an air base in nearby Yuma, Arizona.

At this location, the production built its Saudi base camp, as well as the road between Kuwait City and Basrah-“The Highway of Death,” so-called because of the incinerated Iraqi combatants and civilians whose remains littered the thoroughfare (the only major north-south road in and out of Kuwait, which rendered it a prime target for Allied bombers).

On the other side of El Centro, north of a gypsum manufacturing plant (called Plaster City), lay a section of privately owned land; here the company set down for several weeks on the plains below Superstition Mountain.

One pivotal scene shot in this location showed Swoff’s unit enduring friendly fire from a passing F-14 jet (which was rented by the production), with the aircraft buzzing the Marines a few hundred feet above their heads-obviously, the crew experienced the impossible nearness of the jet as well.

The proximity of a fighter jet was not the only challenging aspect of filming within range of Superstition Mountain. The Navy’s Blue Angels (training nearby) made some unscheduled passes over the area during filming. The production was also beset by violent windstorms that literally sandblasted everything and everyone within miles; a few shots of miserable soldiers enduring sandstorms actually show the somewhat miserable actors enduring real sandstorms while filming.

From the southernmost points in California, the company moved across the Mexican border to a 100-mile stretch of salt flats in Baja-the Mexican government had fortunately granted permission for filming. Mendes and his crew chose the area for its flat, wide expanses, where scenes could be filmed in which the vista appears to stretch into infinity on all sides. Specially constructed (and strictly supervised) roads had to be constructed into the barren environs, as the flats are a protected wildlife area of Mexico.

“We went to the salt flats in Mexico to take advantage of about 270 degrees of endless, surreal desert that is very much like a character in the film,” says executive producer Sam Mercer. “We only had two weeks down there and lots of scenes to shoot at a time-and we’d already been on the road for about 10 weeks. There were a number of challenges, from getting 350 crew members across the border to keeping the morale up, not to mention an hour-and-a-half of travel every day…the set itself was located seven miles in from the nearest asphalt road.

“Our biggest challenge, though, was figuring out how we could turn this environment-where there was literally nothing, in the middle of nowhere-into a working film set,” says Mercer. “First, we conducted a technical scout to determine where our guys were going to pitch their tents and build the berms [dirt mounds] that would protect them. Once we pinpointed that, we had to figure out how we could logistically get the company there. We had to create an infrastructure for ourselves, including a road system, water, power, security and lights at night. It became our own military operation.”

But into every such Herculean undertaking a little rain must fall… and in the case of Southern California and Northern Baja, Mexico-in the spring of 2005-it turned out to be a series of downpours.

“We couldn’t have predicted that this was an El Niño year, and we’d run into rain problems throughout the shoot,” says Mercer. “The weather slowed up construction severely at the Mexican site, where the normally hard, dry flats were turned into muddy quicksand. The set kept getting washed away, and the bulldozers kept getting stuck-it was horrendous. But luckily, the sun came out literally the weekend before we started shooting there, dried it up and it all worked out.”

Both creatively and logistically, the filming of Jarhead was a unique challenge. Director Mendes envisioned a movie that would tell the story of what had been mainly an air war from the point of view of the infantry below. In realizing that vision, he collaborated with five-time Oscar-nominated cinematographer Roger Deakins to come up with a photographic style that would convey not only the chaos of combat, but also the intimacy of shared missions, motivations and misgivings amongst an ad hoc fraternity of fighting men.

“This experience has been interesting in that it’s involved my throwing out a lot of the stylistic things I’ve used in my other two movies,” supplies Mendes. “Working with Roger Deakins, we decided that a handheld camera would allow more fluidity and improvisation. Roger is so skilled that he can follow the movement of a scene without relying on blocking and actors hitting marks-that really helped create a flow to the work. I also found that I was better able to react to the changing relationships between actors as they naturally emerged during the shoot.

“For American Beauty I used a series of Magritte-like images and compositions; on this one, I went in with very few compositions already in my head. What I felt coming out of rehearsals was a kind of human energy and life force, and I thought we should respond to that and have nothing pre-determined. I enjoyed it hugely.”

The device Mendes and Deakins most frequently employed is one of the oldest in film lexicon: the point of view. “There is no unbiased view. I’ve deliberately avoided the master shot,” says the director. “My starting point has been Swoff or what Swoff is doing. I’ll start on a close shot of him or enter a scene with him and see what he sees. So my journey has been through the character rather than through an objective, cool, uninflected gaze.”

Reinforcing the idea of a story told at ground level, Mendes and Deakins eschewed any shots that take the viewer out of the realm of what is visible from the soldiers’ viewpoint. Mendes explains, “There are no `God shots,’ no huge crane shots, no ‘copter shots that show us the whole desert and tiny ants crawling across it. Everything’s filmed from eye level and very little of it is on tracks. Camera operators move with the actors, at the same speed as the actors, and there’s rarely an unmotivated move.”

When it came to assembling the feature, Oscar-winning editor Walter Murch was committing to fashioning a visual equivalent of the memorable story Swofford-and now Mendes-wanted told. “I was struck by the peculiarity of the war. I feel the authenticity of the voice, which was both sympathetic and supportive of the predicament in which they found themselves. The film has a great variety of tones in it, which really appealed to me from the start. And I wanted to emphasize all of these-the humor, the violence, the seriousness-and create the greatest range possible.”

Murch also had a distinct feeling of déjà vu during a particular sequence: “There is a fragment of Apocalypse Now both in the book and in the film, which is a film I worked on 27 years ago. The soldiers are watching it, singing along and repeating the lines. It’s a rather interesting concept to be at both ends of the tunnel.”

Much in the same way that filmmakers had to create a functioning motion picture set in the middle of desert salt flats-literally something out of nothing-post production effects artists at the world famous ILM studios were charged with creating effects beyond the scope of what could be accomplished by physical production during principal photography. Visual Effects Supervisor Pablo Helman and his team of 80 were informed by the director that in order to maintain Swofford’s subjective point of view-and keep the viewer from being pulled out of the story by obvious film wizardry-the visual effects were to remain “invisible.” Because there was to be no epic point of view in the film, the effects that Swoff’s story called for-everything from burning Kuwaiti oil wells to dream sequences, scorpion fights to ritual brandings, and even something as simple as a group of soldiers discharging their rifles into the night sky or a horizon that had to be extended-needed to remain in-scale with the personal observances of the narrating Marine sniper.

Helman offers, “Sam’s approach to visual effects is unique in that he’s not thinking about them as being big moments, like `Wow!’ This film, in particular, was about effects used to re-create a specific environment. He’s meticulous about everything, from the placement of smoke to the removal of a shrub. I think that has to do with his theatre background. In theatre, that creation of the illusion of reality is very important-it’s difficult to get people to believe what they’re seeing is real, because it never is real.”

To begin with, the desert locations had been scouted during the summer preceding the start of principal photography…filming then took place the following rainy, winter months. A lot of these formerly brown desert locations were now verdant, so anything that would not be indigenous to the deserts of the Middle East had to be removed.

The scenes showing civilian planes depositing Marines in Saudi Arabia involved more than simple removal work (although a nearby factory, billowing white smoke, did have to be magically eliminated by ILM). The surrounding countryside was replaced with desert, the tarmacs were extended and the scene was filled with planes (all of which received custom digital paint jobs), troops and ground vehicles that didn’t really exist during filming. The final shot was a combination of the original plate shot, some digital map background, stills of the planes and shots of models of the aircraft.

To fashion the Bosch-like hellscape of the flaming oilfields (which shot burning crude 400 feet into the air), a single ignited oil well was filmed from a variety of angles and distances. Those different shots were then turned into a library of fires from varying points of view, which were then used to create three separate types of oil fires. When Swofford’s battalion first comes upon the fields, they are burning in full daylight. Later, as they draw closer, the fires are so big that they produce an imposing cloud of smoke-also, the spewing oil is now raining down-so everything is seen in half-light, as if the troops are nearing an encroaching storm. Finally, after sunset, soldiers are lit by the hellfire glow through the smoke, which hangs over everything like a dense fog.

A variety of techniques aided in building the final scenes of the troops in the vicinity of the burning wells. The day scenes were augmented with flames, along with digitally created electrical towers (to provide scale) and the blackened shells of the burned-out vehicles; the dark, oily sand was also extended beyond the horizon and shimmering pools of oil reflecting the light were added. The half-light scenes were digitally enhanced by imposing a dark canopy onto the film-an enveloping shroud that enclosed the actors in smoke and raining oil. For the night scenes, actors were first shot in a soundstage against a massive orange light array; the instruments themselves were later removed, leaving only the flickering light. The scenes were then composited with elements of smoke, fire and footage shot of night clouds underlit by the actual burning off of the production’s excess fuel (serendipitously observed by effects crewmen returning to their hotels one night, who set up their cameras and filmed the otherworldly view of the glowing horizon the following night).

Additional effects work provided the visuals that on-set safety and humane animal practices prohibited, including: the explosion of an air traffic control tower blown away by fighter jets; the branding of “USMC” into the flesh of a deserving soldier; the to-the-death battle between two scorpions; and the discharging smoke and muzzle flashes of tracer fire from a platoon of Marines shooting their weapons into the desert sky.

In addition to the creation and augmentation of the visual environments featured in Jarhead, an aural landscape comprised of score and soundtrack music was also shaped. The influence of Vietnam is heard in a small group of songs featured on the film’s soundtrack (Swoff even complains at one point, “Can’t we get our own music?”): The Doors’ “Break On Through” and T. Rex’s “Bang a Gong.” But as teenagers/young adults away from home in 1989-90, the soldiers also seek a little comfort by listening, dancing and partying to popular music from that time: Talking Heads’ “Houses In Motion,” C+C Music Factory’s “Gonna Make You Sweat,” Naughty By Nature’s “OPP,” Social Distortion’s “Ball & Chain” and Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” A few, darkly funny music references also appear-Bobby McFerrin’s endlessly upbeat “Don’t Worry Be Happy” plays over Swofford’s arrival at Camp Pendleton, following his less-than-welcoming experiences at boot camp; and when Swoff shows up without an instrument to audition as the unit’s bugler (a non-existent position), Staff Sergeant Sykes requests that he play Stevie Wonder’s “You Are the Sunshine of My Life”…with his mouth.

Ultimately, the goal was to have a movie told by the Marines rather than a movie about the Marines. Anthony Swofford summarizes when he says, “The grunt’s life is much different than what the general public supposes. It’s a mixture of boredom, excitement, fear, longing, sadness… And there are details that are really important in the grunt’s everyday life-friends helping each other write love letters, rehashing stories, the need to have listeners. My friend next to me will listen to a story I’ve told 20 times because he knows that it’s important for me to tell that story.

“What the public can learn from these details,” concludes the author, “is that they’re young men off to fight. They’re caring, vulnerable, but they’re also tough and crude. They’re human and they have faults…but they’re also doing good work for the rest of us.”

On Having Jarhead Made Into a Film

“After I’d finished writing Jarhead in the summer of 2002, the possibility of interest from Hollywood was first discussed. Ron Bernstein, my agent in Los Angeles, first read the book in manuscript form, and during November he began distributing the book in Hollywood. While most parties responded positively to the story, the readers were unwilling to take a chance with the book while the country was preparing to go to war. – Anthony Swofford

In April of 2003, interest in optioning the book increased. I met with Doug Wick while I was in L.A. for the Los Angeles Times book fair. He lived around the corner from my hotel, and he arrived for our meeting on his three-speed bicycle. I thought this was super cool, antiestablishment and smart. And I wanted someone super cool, antiestablishment, and smart producing an adaptation of my book. With a script of Jarhead in Doug’s bicycle basket, rather than sitting on the passenger seat of another producer’s sports car, I thought it might have a chance of being made and avoiding high-speed collisions.

Shortly after my meeting with Doug, he and I had a conference call with Bill Broyles. I admired Bill’s work, both his journalism and scripts, and I immediately felt he was the writer to adapt Jarhead. He knew the book extremely well, quoting characters, narrating scenes, naming page numbers as if it had once been his own story. And in a way, this was true. He told me about joining the Corps and going to combat in Vietnam, and I understood that in the men that I’d served with and written about Bill recognized some of his own fellow Marines-the same dark absurdities, the same brilliant moments of despair and love and honor, the life-altering pitch of battle. The three of us agreed that there were certain scenes in Jarhead the book that had to make it into Jarhead the movie.

I was happy to read Bill’s drafts and undertook a self-study of the craft of scriptwriting while reading draft to draft. By May of 2004, Sam Mendes was attached as director, and I was thrilled. Sam’s prior films showed mastery of the form and a deep understanding of storytelling and characters; these earlier films were artful and risky- elements I knew Jarhead the film required. That month, I met for a day with Sam and Bill in New York, and Sam worked like a sponge-soaking up any and all information I told him about events that didn’t make it into the book, or further characterizations of some of the members of my platoon. Sam’s excitement for the film was infectious. He, too, quoted me back to myself, and he knew the book scene-to-scene. I sensed that he would direct the best possible adaptation of Jarhead: a film borne from the source, but still its own work of art and entertainment.

Late in the summer Jake Gyllenhaal was cast for the role of Swoff, and I was pleased with this development. I’d loved Donnie Darko and The Good Girl, and I felt that his onscreen presence was such that he would capture the controversial bloodlust and existential angst of the young jarhead going to war.

I visited the set during the last week of rehearsal and met Jake. He was committed to playing the role authentically and intensely. It was bizarre to meet the other actors and guess who would be playing whom: for certain, they all looked like young jarheads. One morning while waiting for Sam to call a meeting, the actors joked back and forth and insulted one another, and I felt like I was among some of the same men I’d served with-nervous, hungry, lonely and committed to a cause. I visited some of the sets, including my high school bedroom. On watching the swirl of activity, sets being built, young actors being thrashed by Jim Deaver, Broyles looked at me and said, “Crazy to think all of this came from a book you wrote alone in a room, sitting in your underwear.”

I didn’t visit locations or the set during filming, and I think Sam and I agreed this was best without needing to speak about it. I wouldn’t want a book editor visiting me in my office while I’m in the middle of writing a chapter, to say nothing of a reader.

Sam showed me the film in August of 2005. He and Walter Murch were in the room. After a few scenes I got used to an actor on screen being called Swofford. I recognized the story of Jarhead being told, the intense narrative tale and the more subtle and nuanced psychological and metaphysical storytelling strands that punctuate and intensify the war experience for Swoff and his cohorts. War in the real world is about winning, but war in art is about the expansion of feeling and the explosion of emotion, meaning and beauty.”

These production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Jarhead

Starring: Jake Gyllenhaal, Jamie Foxx, Peter Sarsgaard, Lucas Black, Chris Cooper

Directed by: Sam Mendes

Screenplay: William Broyles, Jr.

Release Date: November 4 2005

MPAA Rating: R for pervasive language, some violent images and strong sexual content.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $62,658,220 (64.7%)

Foreign: $34,231,778 (35.3%)

Total: $96,889,998 (Worldwide)