The nation is recasting itself as a glamour and eco-tourism destination, but its African-inflected culture is what lulls you.

I was trying not to slip as I traipsed over the stone pavement in the drizzle at the old fort at Port Royal in Kingston, the “wickedest city in Christendom,” a warren of iniquity and plunder, a den of pirates and buccaneers and the core of British naval power in the Antilles for 200 years.

As a retired coast guard captain who was born there and lived nowhere else in his 60 years led me around, conjuring up scenes of mayhem, killers, whores and smugglers, I scanned the remains of the fort, nearly deserted that morning, and saw nothing that remained of the glories past. Ruminating about the eerily quiet grounds, the captain sighed and recalled the historic turning point of the Port Royal story, the midday hour on June 7, 1692, when an earthquake toppled most of the city and 2,000 people into the sea, the day Port Royal became a ghost town.

On some islands, the tale would be a defining one, but here, it was just a slim chapter in a dramatic history. Jamaica was born out of conflagration. Fire and brimstone, slave rebellions and insurrections, pirates and buccaneers, hurricanes and earthquakes. It was inhabited by Taino Indians, who named it Xaymaca, and shaped by European conquerors, first the Spanish, then the English.

The British turned the island into a huge sugar plantation, its wealthiest colony in the Caribbean and the hub of slave trade in the Americas. Planters built magnificent houses high above their sugar cane fields, and lived lives of idleness, gorging on drink and wanton sex with slaves.

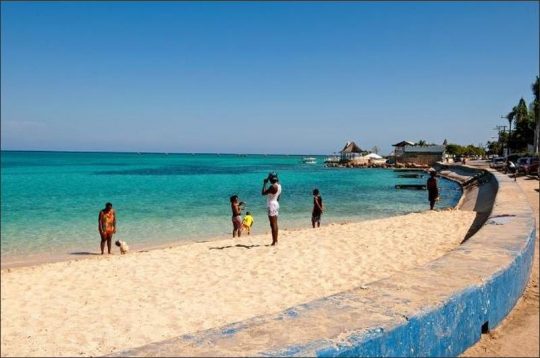

At the center of Jamaica’s ethnic and political complexity is race. As in Antigua and on other Caribbean islands, the social and economic division between mostly white “haves” and mostly black “have-nots” runs deep. Like other Caribbean countries, Jamaica is demanding reparations for slavery. Old grievances and injustices drive much of the political violence, gang crime and economic problems that have bedeviled the island.

But it seems something is changing. The government is stable after long periods of tumult, and it is pushing to rein in crimes against foreigners, gang-and-drugs shootings, and evangelist-reinforced homophobia. The economy is still wobbly but showing some signs of health, and tourism, the island’s No. 1 industry, on which many Jamaicans depend for a living, has risen to at least 1.5 million visitors a year.

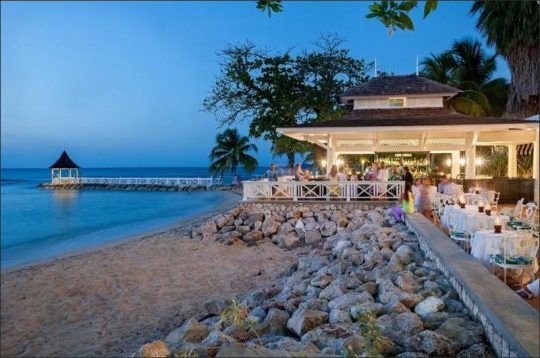

With such high stakes in tourism, the island has begun looking beyond its traditional market, the sand-and-sun visitors and the stable of honeymooners who reliably fill the giant middlebrow Jamaican-owned Sandals and Couples resorts. Jamaica has been promoting celebrity and Hollywood, like the seaside villa “GoldenEye,” onetime retreat of the James Bond creator Ian Fleming and now a resort where one night in the least expensive cottage can set you back $1,400 in the high season.

Glossy videos and magazine advertising showcase a paradise island of multiple attractions including eco-tourism, bohemian tourism, spa and wellness tourism, even small-bore niche tourism like Jewish Jamaican Journeys. It’s an all-out campaign to drum up travelers to Jamaica’s alchemy of nature, adventure, night life and sensuality.

Jamaica has, of course, been a player in the Caribbean tourist game, but competition is stiffer and so are the stakes now that Cuba has opened up and inched ahead of Jamaica in the number of visitors in 2015. Jamaica already lags well behind the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, but it hopes that new mega-resorts and other investments will create badly needed jobs and energize the private sector.

With a per-capita income estimated at $9,000 (it’s $15,200 in Puerto Rico and $9,700 in the Dominican Republic) and an approximate 16 percent unemployment rate, Jamaica is grappling with the steady exodus of thousands of its 2.9 million people to New York, Miami and London.

With few options but to expand tourism, which makes up about 27 percent of the nation’s revenues, the government passed development and casino legislation that will bring the first casino-hotel resort to the island, Celebration Jamaica Hotel and Resort, a 2,000-room, 90-acre project set to open in a year or two in Montego Bay. The resort has a Canadian company behind it, but much of the new tourism investment comes from Spain and Mexico, posing a challenge to longtime Anglo-American dominance.

For all the three centuries that Britain ruled Jamaica, though, the island’s deepest influence is not English. It is African. It is folk magic, spiritual and superstitious. It is musical, the poetry of the hills and the streets, the rhythms you hear in the way Jamaicans speak, the imploding pulse that runs from east to west, from the resort-strewn north coast to the rougher south, through bamboo-shaded foothills and cloud-covered peaks and the wind-driven tides that roll up on this island of old myths and spiritual power.

Folk magic out of West Africa, not unlike Haiti’s voodoo and Cuba’s Santeria, feeds the Jamaican belief in superstition, witches and ghosts. Magic runs through a pervasive fundamentalist and evangelical Christian society that breeds revivalist cults that speak in tongues and believe in spirit possession. Rastafarians are something else. Born out of poor and black Jamaicans, they worship inner divinity, hold ganja smoking as a sacrament, and are as essentially Jamaican as reggae.

“Reggae is synonymous with social consciousness,” a young Jamaican woman told me. “It means black empowerment. It means Marcus Garvey (the father of the black power movement). It means Rastafarianism.”

Folk magic out of West Africa, not unlike Haiti’s voodoo and Cuba’s Santeria, feeds the Jamaican belief in superstition, witches and ghosts. Magic runs through a pervasive fundamentalist and evangelical Christian society that breeds revivalist cults that speak in tongues and believe in spirit possession. Rastafarians are something else. Born out of poor and black Jamaicans, they worship inner divinity, hold ganja smoking as a sacrament, and are as essentially Jamaican as reggae.

“Reggae is synonymous with social consciousness,” a young Jamaican woman told me. “It means black empowerment. It means Marcus Garvey (the father of the black power movement). It means Rastafarianism.”

This was the Jamaica that I wanted to get to know better. So after lunch at the historic Devon House in Kingston, the former estate of Jamaica’s first black millionaire, I made the rounds of several history museums with the chairman of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust, Ainsley Henriques. As we browsed through rooms of ancient artifacts, pictures and other paraphernalia, Jamaica’s heroes came to life. There was Paul Bogle, hanged after the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865, and Nanny of the Maroons, who led slaves to freedom in the Blue Mountains, and Sam Sharpe, hanged after the Christmas Rebellion of 1831. More recently, there was Norman Manley, the Oxford-educated nationalist who helped bring about independence in 1962. His face on wall-size posters in airport corridors greets Jamaica visitors.

And there’s Bob Marley. There’s a museum outside Kingston for the reggae icon. He’s the myth, the mystic, who spoke to God, they say, who conquered the world. But I didn’t have to go look at the museum. All of Jamaica is a Bob Marley museum. A stream of gifted Jamaican musicians cycled through mento to calypso, jazz, rhythm and blues, and ska. Then came Marley, son of a white British officer named Norval Marley and a black woman, Cedella Malcolm Booker, and with Bob Marley came reggae, and reggae took everything in its path.