Greece has always looked toward the sea and lived by it. Of necessity she must continue to do so. Because of her geographical position and because of the limited resources of her land, the Greeks have been a maritime people since the earliest times. The mountains which break up the land seem to push the people into the sea, and indeed they make land travel and land communications so difficult that by comparison sea travel has always seemed simple. The land itself is so lacking in fertility that extensive agriculture is impossible. Thus the Greeks have been forced to import a large part of their food and to turn to the sea to gain their livelihood.

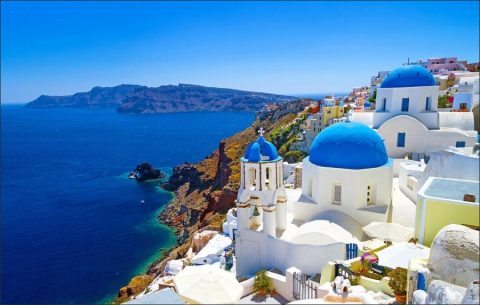

In Greece, the sea seems to be everywhere. The Aegean, the Ionian, and the Mediterranean all wash Greek shores, and these shores are so cut up and so strewn with islands that the sea penetrates everywhere. The coastlines and islands in turn shelter the sea and do away with the fear men have always had of vast unbroken stretches of water.

The Greeks are not such a people as would fear the sea, no matter how far it stretched. By nature they are adventurous and enterprising. Their love of adventure makes them good sailors, and added to this their capacity for enterprise makes them the best of sea-merchants.

Seamanship is an old Greek tradition. Children have been trained from the cradle to become expert sailors. It has been customary for seamen to take aboard ships and sailboats children ranging in age from 6 to 13 so as to accustom them to the sea. When an island was sighted, the children were called on deck, told the name of the island, its ports, and the most navigable routes around it. If, on the next trip, they had forgotten, they were punished. In like manner, children were thrown into the sea to teach them to swim. Nothing was overlooked in an effort to make them skillful and brave seamen.

The skill of Greeks at sea includes not only seamanship but also trading. The Greek was and is a sailor-merchant. There has never been absentee ownership of Greek ships nor have Greeks put their money in enterprises involving ships run by others. Even today, when there is a class of rich Greek shipowners owning sometimes large numbers of ships, such owners have nearly always been identified with ships and are in general successful sailor-merchants.

Nor has shipping been for the Greeks a speculative enterprise only. The Greek is a navigator in the true sense of the word. He possesses ships not only when profitable; he keeps and buys them even when shipping is passing through economic crises and is operated at a loss. The Greek has a great attachment for a ship. He looks after it, cherishes it and is grieved by its loss. He names it after those he loves best: his mother, his wife, his child.

Shipping has been important to Greece from the dawn of history since through it Greece was provided with food. The scantiness of arable land and the overcrowding of the cities, have always forced the people to turn to the sea. Out of this arose the instinct of the Greeks to colonize.

The seafaring Greeks at the dawn of history had colonies. We know much of the period beginning about 750 B.C. when the Greeks settled both shores of the Aegean, as well as the coastline of the Black Sea, and the littoral of Southern Italy and Sicily. Pushed by their enterprising and adventurous spirit, the Greeks sailed as far as the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf. Jason and the Argonauts left the shores of Greece more to explore the commercial possibilities of the Black Sea trade than to search for the legendary Golden Fleece.

After the founding of Constantinople, the Greeks dominated the commerce of the Black Sea and the area about the mouth of the Danube. Similarly, their success in the Trojan War enabled the Greeks to push their trade in the Near East. Greek ships in time sailed to the English Channel, to East Africa, to Spain, to the East Indies, and to Southern and Eastern Asia. The Greeks established a colony at Marseilles and sent boats up the Rhone and down the Loire.

The rise and fall of the Greek power have been closely associated with the changing fortunes of Greek shipping. The advice of the Delphi Oracle that wooden walls would save Greece expressed a national conviction no less than a counsel of defense against the enemy. “From the very beginnings of history that particular type of culture which for convenience we call Greek . . . has been maritime.”

The Greek merchant marine has always been of two categories: tramp boats and boats that followed fixed routes with regular cargo and passenger service. Through both, it served to spread Hellenic culture and, by the aid of Greek shipping, the Greek Colonies were able to ward off the Barbarians. Byzantium and later Constantinople remained Greek for 2,300 years and during all these years through the Bosporus, under Greek domination, there flowed a free traffic of goods between the countries on the Black Sea and the Greek Mediterranean ports.

In particular the Mediterranean traffic remained in the hands of Greek seamen throughout the classic era as well as under the Roman Empire and the early days of the Byzantine Empire. Even the establishment of the Arabs as a naval power after the middle of the 7th century did not stop it. It is only after the 9th century that the Arab pirates, masters of Crete, began seriously to threaten Greek shipping. Subsequent to the 12th century, Venice, Genoa, and other Italian cities, as the Byzantine Empire grew weaker, took over more and more of the Mediterranean commerce.

When Byzantium fell to the Turks, the Greek shipping industry was destroyed and the merchant marine of the Italian cities and Portugal took its place. But the Greeks were not altogether driven from the sea. Left with tiny boats only, they continued to shuttle between the islands and the mainland and after the fall of Constantinople, they rebuilt, as soon as possible, their ships and again traded across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

Visits: 204