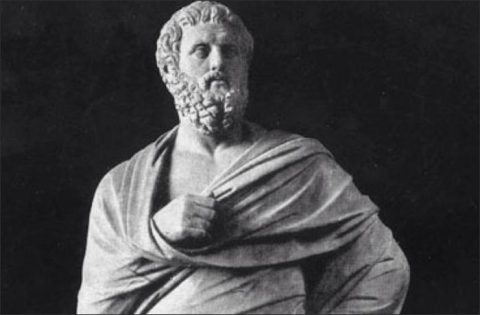

Aeschylus was born at Eleusis, near Athens, in 525 B. C. He began to exhibit tragedies at the age of twenty-five, but did not win the first prize till 485. The Persians came in 490 and 480, and Aeschylus fought against them–his epitaph mentions Marathon, and his celebrated description of Salamis in the Persae makes it clear that he was present. On the invitation of Hiero, the Syracusan king, he visited Sicily soon after 470, and wrote a play to celebrate Hiero’s new city, Etna. After the production of the Oresteia ( 458) he again went to Sicily, where he died. It is said that as he was sitting on the hillside near Gela an eagle, mistaking the poet’s bald head for a stone, dropped a tortoise upon it and killed him.

His works comprised at least eighty plays, of which seven survive, with some hundreds of fragments. Three– Agamemnon, Choephoroe, Eumenides–form a complete trilogy, often called the Oresteia. Tragedy so-called existed before Aeschylus, but it was he who made it a truly dramatic form: we are told by Aristotle that he ‘first introduced a second actor; he diminished the importance of the chorus, assigning the leading part to dialogue’. Each actor could, and often did, sustain more than one role, by changing his dress and mask. Aeschylus’ two actors made possible that collision of personalities and aims which is the essence of drama; and the gradual restriction of the lyrical part left more and more room for strictly dramatic development.

How the Attic drama originated in Doric dithyrambs and in ‘goat-dances’ performed at vintage festivals in honour of Dionysus, the wine-god, has been told, and we have seen how dialogue was introduced (perhaps by Thespis) between the chorus and its leader, and also how the performances were transferred from the vintage gatherings ‘in the marshes’ outside Athens to a primitive theatre on the south-eastern slope of the Acropolis, where later the great theatre of Dionysus was constructed.

In the time of Aeschylus (525-456) various innovations were made, some of them doubtless by him. A second ‘hypocrite’ (i.e. ‘answerer,’ or speaker) was added, so that the narrative and the ‘drama’ (action) became much developed and more independent of the chorus, which now fell more into the background. Masks and costumes were improved and the high buskin (cothurnus, like the Elizabethan chopin) introduced.

Statues, houses and temples, curtains, painted rocks and groves and other scenery, doors for exits and entrances, and other such stage apparatus, began to take the place of the central thymele (altar) round which the old dances had been performed, and, by about 430, movable platforms, wheeled or revolving on pivots, cranes, and other machinery for the descent and ascent of deities, became common. But to the end the classical Attic drama retained much of its original scenic simplicity.

It was always more sculpturesque than pictorial. Sophocles introduced a third, perhaps a fourth, actor; but this number was seldom, if ever, exceeded. Spectacular effects seem to have been almost entirely disregarded, and nuances of by-play and facial expression were made impossible by the great size of the open-air theatres and by the masks of the actors. The one thing of importance–and it must have been exceedingly difficult needing mechanical aids–was audible and effective recitation both of dialogue and of chorus, for text-books were unknown, and the vast audiences would doubtless be eager to hear and criticize the new versions of the familiar legends that generally formed the subjects of these dramas.

It has already been mentioned that Aeschylus fought at Marathon, where his brother Cynaegeirus was killed. Probably he was present also at Salamis and at Plataea, and some believe that the ‘Ameinias of Pallene’ who at Salamis first attacked the Persians was the youngest of his brothers. He first competed for the tragic prize about 499, and first won it in 484.

He is believed to have invented the ‘trilogy’–a group of three connected, or unconnected, tragedies, followed usually by a semi-comic ‘satyric’ play. In 468 he was defeated by the young Sophocles, amidst great public excitement. Cimon in this year brought the bones of Theseus from Scyros, and he with his nine fellow-generals were asked to act as judges, and decided in favour of Sophocles.

It has been said that either on this account or because he was beaten by Simonides in the composition of the Marathon epitaph (which, however, was in 489!), or else because he was accused of revealing the Eleusinian Mysteries or of impious language (perhaps in his Prometheus, where Zeus is blasphemed), Aeschylus withdrew to the court of Hiero at Syracuse. It seems, however, that he had already been in Syracuse (about 475-470), where he must have known Simonides and Pindar. Hiero died in 467, and the poet, who was again in Athens in 465, returned to Sicily after the production of his Oresteia at Athens, and died ( 456) at Gela–killed, it is said, by being struck on the head by a tortoise dropped by an eagle, in fulfilment of a prophecy that he should perish by a ‘stroke from heaven.’

Of the seventy or more tragedies attributed to Aeschylus we possess only seven complete, but these seven are more than enough to prove that in dramatic power and sublimity he is, with perhaps the one exception of Shakespeare, the greatest of poets, and in majesty and might of language unrivalled. His plots are simple, and in the earlier dramas there is a want of movement, the chorus sometimes being unduly prominent and using exceedingly obscure language; but the dramatic effect is often overpowering.

“Terror,” says Schlegel, “is his element, and not the softer affections. He holds up a Medusa’s head before the petrified spectators.” His mind seems to have been deeply imbued by awe of mysterious powers–such powers as we hear of in the old religion of Greece and the Orphic and Eleusinian Mysteries. There is constant reference to expiation and purification and the averting of evil, to dreams and oracles and portents and spectral apparitions and to the ancient chthonian (infernal) deities, especially to the primal Earth-Mother. In some passages, says Paley, there is scarcely a word that does not involve some mystic doctrine.

In splendid contrast to this background of gloom, with its sinister Fates and terrific Furies, stand the figures of the gods of Olympus, the benign sunlight deities–Zeus and Apollo and Athene. To these also Aeschylus pays reverence, but rather perhaps as personifications of Nature and agents of those supreme spiritual powers of good and evil the manifestations of whose irresistible will are intimated under such names as Fate and Destiny and Justice and Retribution, and that Infatuation that maddens a man and goads him on to. insolence and impiety and tempts him to “kick against the altar of Righteousness.”

Aeschylus is said to have belonged to the aristocratic anti-popular party of Aristides and Cimon, and to have opposed the innovations of Themistocles. But his glorification of the battle of Salamis seems scarcely consistent with a bigoted anti-naval policy, and his Eumenides is not, as is sometimes imagined, directed against the action of the party of Ephialtes (p. 292), but is rather a recognition of the Areopagus as the supreme court for cases of homicide.

His reverence for the divine rights of kingship is very perceptible, and he seems to have been much impressed by the magnificence of the Persian court. Indeed, one may perhaps trace an Oriental influence in some of his imaginings, which at times are scarcely Greek in their audacity and grotesqueness–a quality noticed by Aristophanes, who makes Euripides ridicule the ‘horsecocks’ (griffins) and ‘goat-stags’ of Aeschylean drama.

No translation can reproduce the splendours and sublimities of the verse of Aeschylus, but some idea of the greatness of his dramatic power may be gained by reading even an unpretentious prose version, not of selected passages, but of an entire play, or, still better, of the great Trilogy–perhaps the mightiest drama in all literature. The pages of a volume on Ancient Greece could scarcely be better filled than with such a version; but I shall have to content myself with giving a brief account of the seven extant plays.

Visits: 284