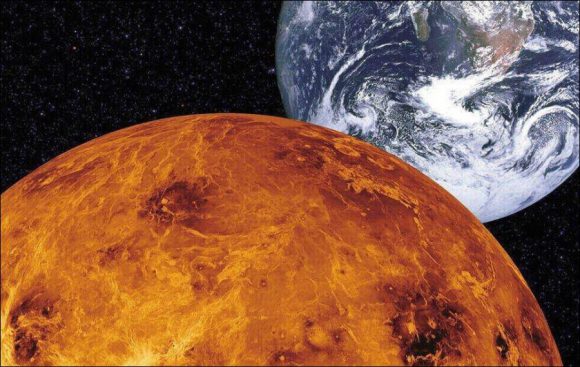

This hot and acidic neighbor, whose surface is covered with thick clouds, cannot take its toll from Mars and the Moon. However, Venus can give us an idea of the fate of the Earth.

The planet, which is right next door, is, in astronomical terms, almost like a twin of Earth. Made of the same materials, the same size and formed around the same star. He would appear almost indistinguishable from our own planet to an alien astronomer who was at light distance from us and observed the Solar System through a telescope. However, one who knows the surface conditions of Venus atmosfer the atmosphere of a self-cleaning oven and saturated with sulfuric acid clouds and carbon dioxide da will also know that this is not something similar to Earth.

How can two such planets be so different in terms of location, formation and composition? This is a question that is busy with a growing number of planetary scientists and encourages a large number of Venus discovery activities. If scientists can understand why Venus is like this, we will understand better whether this Earth-like planet is a rule or an exception.

I’m a planet-based scientist, and I’m fascinated by how other worlds form. I am particularly interested in Venus; because it allows us to look at a planet that was not so different from ours at one time.

Once upon a time was Venus blue

The current scientific view of Venus suggests that at some point in the past, the planet has much more water than today’s bone-like dry atmosphere, and perhaps has enough water to fill the oceans. But as the Sun became warmer and larger (as a natural consequence of aging), the surface temperatures of Venus rose and eventually evaporated the oceans and seas.

As time passed, due to the water vapor accumulated in the atmosphere, the planet came under the influence of an illegal greenhouse that it could not escape. So far, it was known that there was a Earth-like plate tectonics operating in Venus (the outer layer of the planet was cut into large, moving parts). Water plays a vital role in the operation of plate tectonics and effectively terminates this process when an illegal greenhouse effect occurs on the planet.

However, the discontinuation of plate tectonics would not end the earth’s activities: the high internal heat of the planet continued to produce magma that resurfaced and reshaped most of the planet in the form of dense lava flows. Indeed, the average surface age of Venus is around 700 million years; it is certainly very old, but much younger than the billions of years of Mars, Mercury, or the Moon.

Discovery of the second world

The wet planetary view of Venus is just one hypothesis: Planetary scientists do not know what caused Venus to be so different from Earth, or whether the two planets began life under the same conditions. Humans know less about Venus than they do about other inner Solar System planets; because it creates greatly unique challenges at the point of planet discovery.

For example, you need a radar that can penetrate matt sulfuric acid clouds and see the surface. This is a much more challenging issue than the effortlessly visible surfaces of the Moon or Mercury. And the high surface temperature of 470 degrees Celsius means that traditional electronic devices will not survive for more than a few hours. This makes a big difference between the research tools that can work on Mars for more than a decade. Partly due to heat, acidity and the invisible surface, Venus has been deprived of a sustainable exploration program for the last few decades.

In the 21st century, however, two special Venus missions took place: the European Space Agency’s Venus Express, which operated from 2006 to 2014, and the Akatsuki spacecraft of the Japan Aviation Research Agency, which is currently in orbit.

People didn’t always ignore Venus. Once upon a time, it was the heart of planetary exploration: between the 1960s and 1980s, 35 vehicles were sent to the ‘second world’. When NASA’s Mariner 2 probe reached Venus in 1962, it was the first spacecraft to be successfully sent to a planet. The first images of the surface of this ‘second world yol were sent by the orbiting Soviet Venera 9 vehicle after being processed in 1975. And the Venera 13 research vehicle was the first spacecraft to send information from the surface of another world. On the other hand, NASA’s last mission for Venus was Magellan in 1989. This spacecraft, almost before the planned death in the atmosphere of the planet in 1994, radar imaging of almost the entire surface.

Return to Venus?

Over the last few years, several new NASA Venus missions have been proposed. NASA’s latest research tool is a nuclear-powered probe called Dragonfly, sent to Saturn’s satellite Titan. However, a more advanced technology proposal was adopted to investigate the composition of the Venus surface. Other tasks considered include a tool produced by ESA to map the surface in high resolution, and a plan of Russia, which wants to preserve its heritage as the only country successfully landing on the surface of Venus.

About 30 years after NASA set out for our hell-like neighbor, the future of Venus discovery seems promising. In contrast, a single task – an orbital radar and even a long-lived surface exploration tool – is not enough to solve all of the planet’s extraordinary mysteries.

Rather, we need a sustainable exploration program to bring our knowledge of Venus to the same level as Mars or the Moon. This business will take time and money, but I believe it’s worth it. If we can understand why and when Venus came into being, we can better understand how a Earth-sized planet could evolve in a state close to its star. Moreover, under a constantly shining Sun, Venus can even help us understand the fate of the Earth itself.

Visits: 114