Who Watches The Watchmen?

New York, 1985-a world darkened by fear and paranoia. Where regular human beings who once donned masks to fight crime now hide from their identities. Where the ultimate weapon-an all-powerful superbeing-has tilted the global balance of power, pushing the world implacably closer to nuclear time midnight. Where desperate men conjure desperate measures in the stark face of Armageddon.

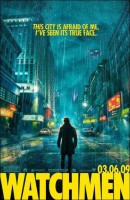

This is the world of “Watchmen,” the big-screen adaptation of the most celebrated graphic novel of all time, brought to life for the first time by visionary director Zack Snyder.

Spray-painted across a wall in the shadows of a dark, gritty placeStateNew York alley is a question that pervades “Watchmen”: “Who watches the Watchmen?” Snyder offers, “Who has the right to say what’s right and what’s wrong? And who monitors those who decide what is right and what is wrong?”

Watchmen first appeared as a 12-issue limited comic book series. It was originally published by DC Comics from 1986 to 1987, then republished as the now-legendary graphic novel. The blood-stained “smiley face” on the cover, the image of a clock face advancing one minute closer to midnight, and the twelve-chapter structure are all emblematic of the richly complex work that has long been credited with elevating the graphic novel to a new art form: Watchmen is the only graphic novel to win the prestigious Hugo Award or to appear on Time magazine’s 2005 list of “the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to the present.” It also earned several Kirby and Eisner Awards.

When it was released, Watchmen resonated with a generation raised with the prospect of nuclear war, not as an abstraction but a palpable reality. It has been praised for giving voice to the anxiety and unease of the times, the fear and awe of power and its abuses, and the cloud of paranoia and impotence experienced every day by average people considered insignificant to the power brokers. In the decades since its publication, it has garnered a legion of diehard fans from all walks of life that continues to grow.

“In the ’80s, there was a lot of paranoia about the Cold War-was it going to escalate and what would happen if it did-and how fragile our society was, how very little would have to be done to completely wipe out everything that we had,” the graphic novel’s co-creator and illustrator Dave Gibbons comments. “That was very real to me. And though it has receded a bit, there are new fears of mass destruction, so I think that paranoia is always going to be there.”

Subverting and deconstructing the concept of superheroes, the story introduced a handful of characters that have been called “more human than super”-real people who deal with ethical and personal issues, who struggle with neuroses and failings and who, aside from Dr. Manhattan, are without superpowers. The original team of heroes, the Minutemen, was comprised of The Silhouette, Silk Spectre, The Comedian, Hooded Justice, Captain Metropolis, Nite Owl, Mothman and Dollar Bill. The next generation of masked adventurers-those at the heart of the graphic novel’s mystery-are Silk Spectre II, Nite Owl II, Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias, and The Comedian, who is the only holdover from the Minutemen. Each is a symbol of a different kind of power, obsession, and psychopathology. A different kind of superhero.

Adding to the book’s mystique-with its intricate, multi-layered storytelling and dialogue, symbolism and synchronicity, flashbacks and metafiction-Watchmen has long been considered both in a class of its own… and virtually unfilmable.

For over a decade, producers Lawrence Gordon and Lloyd Levin held the faith that it wasn’t the latter, nurturing the project and waiting for the right moment and the right filmmaker to bring the book to life in a manner worthy of the work itself. “I read Watchmen when it first came out,” Levin relates. “I was a big comic book fan, but I had never read anything like it. It was the first time that I really connected with a graphic novel, just in the sense of feeling that it was my world, the world we all live in. It’s a great piece of literature. The clockwork nature of the storytelling, how profoundly it deals with the human condition, the epic nature of the story.”

The project fully came together when filmmaker Zack Snyder, while still in production on what would become the blockbuster “300,” expressed to the producers his affinity for the graphic novel and desire to direct it. “With Watchmen, there has always been an element of serendipity, coincidence, and timing,” says Gibbons. “It seemed to be that this was a good time for it to happen, and Zack was absolutely the right person to do it properly. But none of this would have ever come to pass without the patience and passion of Larry and Lloyd, who wouldn’t do it until they could do it right.”

Lawrence Gordon offers, “After having worked for over 15 years to get `Watchmen’ made, I couldn’t be more thrilled. In every aspect of the production-from developing the screenplay to assembling our creative team, from directing the wonderful cast to realizing the film’s look-Zack Snyder did an incredible job.”

Snyder’s goal was to bring Watchmen to life as it was, not updated to the present, not substantially altered, but to be as true to the work as possible with a motion picture. “Zack respected the source material so much that he knew the only way to adapt it was to hew as close to the source as possible,” says the director’s wife and producing partner, Deborah Snyder. “Changing the time period, or emphasizing any of the characters over the others, would never serve the story that’s told in the graphic novel, which has always been more than the sum of its parts. There were aspects we knew we couldn’t include entirely-like Under the Hood, which was Hollis Mason’s chronicle of the Minutemen, the first masked adventurers from the 1930s, and Tales of the Black Freighter-but we knew we could do something with these ancillary bits on the DVD. For Zack, the key for doing this massive project was to always stay true to the graphic novel.”

“People always said Watchmen was the unfilmable graphic novel,” says Zack Snyder. “The story itself is a pretty straightforward mystery, but inside of that, there’s this huge plot that has international intrigue and a super-villain and everything you want from a superhero story. There is a tonal quality to every bit of it, from the interaction of the characters to the design structure, whether it be a flashback or a flash forward, or a parallel story being told. It’s at once very traditional and also unusual in the way that it’s structured. It doesn’t owe anything to any specific genre; it’s just its own, true to itself and all of its characters.”

The screenplay, adapted by David Hayter and PersonNameAlex Tse, maintained the graphic novel’s depiction of superheroes as very human characters subject to the same social and psychological pressures as anyone else. Snyder observes, “With all these characters, you feel that they are deeply loved by their creators, regardless of their flaws or how they’re viewed in a real-life context, or what they point to in other icons of superhero mythology.”

“Watchmen is more complex in that it doesn’t just create an archetypal character; it goes through all the variations of why you would put a costume on, why you would want to fight crime,” Gibbons states. “Are you slightly mad? Are you altruistic? And what would happen if you did get super powers and you couldn’t care less?”

The Masks of “Watchmen”

“Watchmen” unfolds in a world at the brink of war, in which costumed superheroes, called Masks, have been outlawed, driven underground by a society that once revered them but then grew to fear and despise them.

The uniqueness of the project attracted many talents. “We read a lot of actors for the movie,” Levin affirms. “Ultimately the cast that emerged were, of course, talented, but also they absolutely believed in the words that they were saying and in the characters they were playing.”

“`Watchmen’ studies these characters’ politics, their sexuality and their philosophy, their deviances and inadequacies,” says Patrick Wilson, who plays Nite Owl II. “That’s something you haven’t seen before in this genre.”

Carla Gugino, the film’s Sally Jupiter, notes that the prospect of embodying the characters of what she calls “the `Citizen Kane’ of graphic novels” was both daunting and exhilarating. “There was a great amount of responsibility to do it justice,” she says. “There was not one person who felt the need to shine more than anybody else. It was a wonderful true ensemble.”

Cast as Rorschach, Jackie Earle Haley was struck by the opportunity to portray “the humanity behind the mask,” adding, “It explores what the world might be like if people really did dress up in costumes and went into the vigilante business. What are their weaknesses, their morality, the beliefs driving their behavior?”

They also quickly found that Snyder’s enthusiasm was infectious. “I’ve never seen someone more passionate about a project in my life,” says Jeffrey Dean Morgan, who plays The Comedian. “How passionate he is about this novel and making this movie true to it was a sight to behold and it invigorated everybody.”

Even before Snyder selected the cast, fans were trying to select it for him. “About three years ago,” recalls Haley, “people on the `Net were suggesting me for the role of Rorschach. At the time I didn’t know the novel. I looked it up and was fascinated by it. So when I heard the film was going ahead, I was very pumped and fought like hell to win the part.”

The only Mask to openly defy the Keene Act, which outlawed costumed heroes, Rorschach remains vigilant, continuing to haunt the gutters of New York, hunting society’s “vermin”…his mask the last thing they see before he metes out his judgment. Rorschach’s moral compass has only two directions: right and wrong.

“We live in a complex world of shades of gray, but for Rorschach, the world is black and white,” says Haley. “For him, complexity makes no sense. Complexity simply justifies the victimization of himself and everybody who is made to suffer from someone else’s special interest.”

Rorschach’s psychology and sense of honor alike are reflected in the mask he wears, with shifting, mirror image patterns of black and white, like the inkblots of a Rorschach test. “Rorschach has this noirish quality about him,” says Snyder. “He is the detective of the story, but at the same time, he is almost psychopathic in his uncompromising pursuit of justice. He’s a very fascinating character. He comes from a broken family and grew up on the mean streets, and then gradually, through events both in and out of the mask, he became Rorschach.”

The mystery unfolds following Rorschach’s discovery that Edward Blake, also known as The Comedian, has been murdered, thrown from his 30th-floor apartment window. A disenchanted killing machine who has spent his years doing unsavory jobs for the government in both war and peacetime, The Comedian sees the world as a dark place where small acts of brutality or heroism alike make little to no difference.

“The Comedian is as American as can be, but he is also the dark side of what America has the potential to be,” remarks the director. “He rides that edge; he’s always doing some dark job for the government, but he’s doing it as a superhero would do it.”

To Rorschach, he’s nothing short of a super-patriot, an American hero who died in service to his country. Tonight, a Comedian died in New York, Rorschach writes in his journal. Somebody knows why.

Rorschach believes someone is picking off costumed heroes, of which The Comedian is only the first. He sets out to warn the members of the interconnected group that in past years fought by his side-six souls tied together by fate and the desire to make their own brand of justice. His first visit is to Dan Dreiberg, who, as Nite Owl II, was his partner in the glory days of the Masks.

“Dan was probably the closest friend that Rorschach has ever had on the planet,” says Haley. “The police don’t like Rorschach. The citizens don’t like him. None of the other Masks like him. When he stumbles upon this murder, he is going to pursue it all the way to the end. But I also think there’s a little piece of him that sees the murder as a reason the guys should get back together.”

Unlike Rorschach, however, Dan has moved on. Prior to assuming the identity of Nite Owl, Dreiberg had been “rich and bored, with this romantic fantasy of fighting crime, being a superhero, of saving and getting the girl,” says Patrick Wilson.“He has an old-fashioned sense of values. He sees the good in people. When he went out and fought crime, it was about justice and helping people.”

Dan now lives a quiet life and makes weekly visits to his predecessor, the original Nite Owl, Hollis Mason (Stephen McHattie), to reminisce over a beer. “Dan has gotten soft physically, politically, sexually…” Wilson notes. “Without the costume on, he doesn’t have an identity. He has no place in society and feels impotent in the face of its problems. He’s terrified to put the suit on, but you also get the sense he can’t live without being Nite Owl.”

“It’s only when he is confronted with this mystery that’s unfolding-his colleagues being murdered-that he begins to see the potential of putting on the old costume,” adds Snyder. “Once he gets the costume back on, he realizes that that’s who he really is. He’s this sort of Everyman who is lost until he rediscovers his purpose.”

Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias, has already established a new purpose beyond his previous life as a Mask. The world’s smartest man and now one of its richest, Veidt retired before the Keene Act and made his fortune exploiting the masked vigilante era in the form of action figures, cartoons, perfumes, books and movies. Nevertheless, he believes he has a higher calling. Obsessed with the exploits of Alexander the Great and the Egyptian pharaoh Rameses II (Ozymandias is the Greek name for Rameses II), Veidt seeks to perfect the human condition.

Where Rorschach seeks to punish the guilty, Veidt considers those efforts pointless when everything they know could be obliterated at any minute. “Adrian has a bit of a god complex,” explains Matthew Goode, who plays the gilded magnate. “He has this idea that the world needs to be fixed because humanity seems to be broken. We are constantly warring with each other and he believes that no price is too high to get the world to unite in brotherhood.

“That philosophy is in many ways the spine of the movie,” Snyder asserts. “How do you reshape humanity and make it peaceful? Can anyone really have that kind of control?”

“They’re all just fundamentalists, in a way,” says Billy Crudup, who plays Dr. Manhattan, the only Mask with true superpowers. “They see a threatening world where their only recourse is to take matters into their own hands, and their desire to order a disordered world overcomes morality. But Jon believed in the goodness of his country, in following the designs of his leaders.”

Before the accident in a nuclear lab that forever altered his life, Dr. Manhattan was Jon Osterman, the son of a watchmaker, a brilliant physicist and “a quintessential `50s male,” says Crudup, the actor behind the blue light that emanates from Manhattan’s body. Though Manhattan chose to join the informal group of Masks, the others are, by comparison, “people who play dress up,” Crudup states. “They are vigilantes. They don’t believe in the stability of the government. They don’t believe in the community’s capacity to take care of itself. Osterman was the exact opposite: someone who was by the book, believed in the stability of his country and the morality of his government. He did whatever they wanted. And initially after he becomes Dr. Manhattan, he continues to do it.”

The accident transformed Jon Osterman into a superbeing, who experiences past, present and future at once and has the power to control matter itself. “He didn’t put himself back together as mortal; he put himself back together as a deity,” says Crudup.

Comparing Dr. Manhattan to the existence of a nuclear bomb, Snyder remarks, “It became a force in itself in that its existence changed the way we looked at everything. I think in some ways that’s what Manhattan represents-this ability to save us or destroy us at the same moment. The implications of this new power are tremendous: Is he truly on our side? What if that power goes away or turns on us? How do you relate to that as a person? He brings into question so many things about our own way of thinking.”

As Manhattan moves further into the limitless dimensions of time and matter, he commences a gradual disconnection from humanity and ambivalence about its existence. “He has apathy for almost everything, except for the inner workings of the atom,” attests Crudup. “He sees the way the universe works. Humanity has a variable that physics doesn’t seem to have. Physics is an ordered world to be discovered. And human interaction is a chaotic world to be taught through harsh experience. It becomes frustrating and burdensome to the point that I think he just doesn’t care anymore.”

“He longs for a relationship in a sense, but at the same time he’s outside of his ability to connect to humans,” describes Snyder. “He can see your subatomic particles; therefore you become an abstraction to him and it’s hard to relate to that abstraction.

“What would that do to you as a person?” Snyder asks. “What does that do to your relationships with other people, with humanity?”

The one human being with a genuine connection to Dr. Manhattan is Laurie Jupiter, aka Silk Spectre II, who fell in love with Manhattan as a teenager. Laurie is played by Malin Akerman, who offers, “Laurie was head over heels in love with him, but as he grows more and more distant, there’s nothing left for her in the relationship. His work comes before her in her eyes. She feels him falling out of love with her and the more he drifts away, the more she loses her identity.”

After the murder of The Comedian, Laurie reconnects with Dan Dreiberg, who shares her inchoate sense of loss. “Reconnecting with Dan gives Laurie back her sense of being a woman,” Akerman affirms. “Someone is looking at her, for the first time in God knows how many years, as one human being to another. That reconnection reignites the fire that used to be there as Silk Spectre, the need for the adrenaline rush.”

“Their common bond is that they have the same memories of fighting crime,” adds Wilson. “They’ve since become regular human beings just trying to muddle through life without any special powers, moral certainty or superhuman brilliance. Laurie opens Dan up to putting the suit on again. It’s the thing that he’s most terrified of and the thing he wants more than anything. He just needed somebody to look him in the eye and say, `Let’s do it.’”

Laurie had been pushed into the role of superhero as an adolescent by her mother, Sally Jupiter, who had been the first Silk Spectre. “As Silk Spectre II, Laurie learned to fight like a man,” says Akerman. “She was this strong, powerful woman and, in spite of her reluctance to be a Mask, somewhere inside she loved it.”

The vampy Sally Jupiter now lives in a retirement community in California and spends her time reminiscing about the limelight she once enjoyed as a rare female crime fighter. “Sally is from the old school of superheroes, the same as The Comedian,” says Snyder. “She represents to me the golden age of superheroes. They were almost like movie stars then. So, in a lot of ways, she’s like a faded movie star who was never able to recapture that same glory and spotlight that she had in her heyday.”

Carla Gugino describes her character as someone who “likes to think of herself as a little more polished than she really is. Sally definitely wanted to fight crime but she also wanted the attention. As she aged she foisted that upon her daughter. Sally’s a very complex character who has been through a lot, but much of the drama was self-induced. This is a woman who in her heart of hearts is in love with The Comedian, even though they were never really able to be together.”

Sally and Edward Blake, aka The Comedian, were intensely attracted to each other during the golden years of the Minutemen, the original group of superheroes. But their relationship was irreparably marred by an encounter that changed both their lives. “That was the moment that everything changed for Edward Blake,” asserts Jeffrey Dean Morgan, who plays the role. “That’s when the true lone wolf came about. He realized he didn’t have the skills to convey his feelings; instead, he hurt the woman he’s in love with. After that, his whole life is spent virtually alone. I don’t know what kind of existence that would be for somebody. I think there’s something incredibly sad about The Comedian. I think he wants so much more than he’s been able to have in his life. He’s a lost soul. The only time he isn’t alone is in the midst of a war, with his buddies behind him. He laughs through the worst of it because the little things don’t matter for him. Even death doesn’t matter to him – until that moment when he realizes what’s really going on.”

Morgan provided at once the charisma and the brutality of his character. “There’s duality in every role, but particularly in The Comedian,” says Deborah Snyder. “When he’s firing on a mob during riots, it makes you wonder, `Who’s better, the angry mob or The Comedian?’ The way Jeffrey plays him, you shouldn’t really like this guy and yet you do.”

From New York to Mars, plots and conspiracies are unfolding with the fate of all life on earth suspended in the hands of a few. As the Doomsday Clock moves to near-midnight and humanity falls into its shadow, these masked heroes-lonely or megalomaniacal, compassionate or disturbed, loving or outcast, human or superhuman-must decide if they can make a difference, if the world is theirs to make or if, in the end, their fate is to simply find comfort in their mission or each other as the pieces of history fall into place around them.

“Who makes the world?” muses Dave Gibbons. “I guess it’s the people in it. It’s planning, because people do nothing if not plan. But, at the end of the day, I believe plain luck and happenstance are much more important factors than any of us thinks; they’re woven throughout the fabric of reality. No matter how carefully you plan or however many people want something, it still doesn’t mean it’s going to happen. I think in the end, you have to bow to the greater power of the universe.”

From Panels to Frames

Snyder’s goal, and that of the cast and filmmaking team he built around him, was to create an experience true to the feeling of the graphic novel and unlike anything put to screen before. “There’s massive spectacle in this movie,” says the director. “It’s that mix of hard emotional reality with Dr. Manhattan on Mars in this giant glass palace, floating above the Martian landscape, or Manhattan 200-feet-tall walking through the jungles of Vietnam. It goes back and forth between action and what that action means to the characters. We tried to push the storytelling to the very edge, and to push the look as far as we could to truly bring to life the experience of the graphic novel.”

Using the graphic novel and the screenplay as a starting point, Snyder storyboarded the entire film to lay out his vision for all involved in what would no doubt be an epic undertaking.

Production designer Alex McDowell remembers, “Zack opened his books of storyboards and that in itself was revelatory. Then, on the opposite page, he had picture references and extensions of the ideas contained inside the boards. So, we had two incredible volumes that we constantly referenced: the graphic novel and Zack’s bible.”

But where the visual landscape of “300” was created almost entirely on a computer, for this film Snyder wanted to set his characters on solid ground. “With `Watchmen,’ the sets are so intimate,” he notes. “As we started to build New York City, we realized these characters are going to be walking down these streets. You might as well build the whole thing. So, we ended up having something like 200 sets in the movie.”

But the film also encompasses less earthly vistas. “`Watchmen’ is this gritty, real story, but yet a quarter of the film takes place on Mars,” Snyder continues. “And other scenes take place in placeAntarctica, at a retreat built by a millionaire ex-superhero. So there are operatic aspects to it as well. I’m naturally interested in those big thematic visions of reality. That’s not to say Rorschach doesn’t walk down a seedy 42nd Street world, but at the same time, there is this giant glass palace that’s built on Mars. There are flying machines, huge blimps hanging over the placeStateNew York skyline, and other things that we were able to layer in. I think that that’s part of the strength of this visual approach.”

One set among the many created for the film would be entirely digital: Dr. Manhattan’s Glass Palace on Mars.“The design is a combination of quantum physics and a clock,” comments McDowell. “There are layers and layers of references to clocks and watches in `Watchmen’-the ticking clock of the nuclear countdown, the watch Osterman wears and then leaves behind, setting off the chain of events that leads to the creation of Dr. Manhattan. So, there’s some idea that the Glass Palace is an elaborate clock mechanism that he creates in reference to his father.”

With so many sets, including an entire city, needing to be constructed, the next step, says executive producer Herb Gains, was “to figure out where we could shoot this movie. As Zack continued to draw the boards and I started seeing more and more of his vision, I realized that even under the best of circumstances any single location was going to fall short of what he required. It became obvious that we had to control our own destiny, to build everything and create the environments with very little location work, which is essentially what we did.”

McDowell created a large schematic that incorporated images from the graphic novel, set designs, and other references to keep track of the multiple sets and characters and the timelines that define them. This schematic became a valuable tool for every member of the crew. “As we developed the language of the production, we used this as a way of feeding all the necessary beats back to all the departments, from set dressing, construction and costumes to the actors,” he explains.“It was really a vital part of how we planned the film.”

Building the World of “Watchmen”

Filming was accomplished at several locations around Vancouver, Canada, and a number of sets were constructed on four stages at CMPP Studios (Canadian Motion Picture Park). In addition, a new backlot was built from the ground up on what once was a vast lumber yard on the outskirts of town. There, McDowell and his team built from scratch the New York City that Watchmen fans will recognize-from the Gunga Diner to Rorschach’s alley to The Comedian’s high-rise apartment.

“In `Watchmen,’ there are many subplots and threads layered within the imagery,” observes McDowell. “It’s very, very dense. As a production designer, one of the tasks is to set up an environment that the audience can enter and become completely immersed in, and then your work becomes part of the storytelling process.”

Production utilized mostly local crew, under department heads from both sides of the border. Everyone was provided with a binder of source materials that included extensive clippings and interviews with the creators, and the graphic novel itself, which was referenced daily. “Putting together a crew is just as important as casting the picture,” says Gains. “We often had activity on four stages every day for weeks, different units shooting and Zack going back and forth. It wasn’t just a job; there was passion. We all knew we were working on something magical.”

Under McDowell’s direction, the crew compressed the entire city as represented in the graphic novel into three intersecting streets. The relatively upscale Brownstone Street incorporated Dan Dreiberg’s apartment and also that of the first Nite Owl, Hollis Mason, while Blake Street housed The Comedian’s high-rise apartment building.

Blake Street was eventually converted to Riot Street, where the Owl Ship lands during a scene depicting the Keene Riots. The central hub street, intersecting both Riot and Brownstone and representing the seedier part of town, was called Porno Street. An off-shoot, called Fight Alley, became the site of a major fight sequence between Dan and Laurie and the Knot Top gang.

Also built at an intersection on the backlot was the Newsstand, a key element from the graphic novel containing the overlapping stories presented in the Tales of the Black Freighter novel-within-a-novel chapters. Snyder shot those sequences specifically for a planned feature on the future DVD.

“One of the things that was great about working with Zack,” says McDowell, “is that he was as fanatically interested in finding the Easter eggs in the graphic novel and pulling them into the film. On some films, you make a decision that you’ve gone deep enough; let’s just shoot the thing. But Zack shares my same obsessive interest in the fine detail, so it was great fun to do.”

In the middle of the New York environments, McDowell’s team situated the placeSaigon bar, where Edward Blake has a run-in with a former Vietnamese mistress, with a full exterior and an interior shooting space with a depth of 40 feet. “We created a little piece of placecountry-regionVietnam right in the middle, with Brownstone Street on one side and decrepit New York on the other side,” McDowell notes.

One of the production designer’s favorite sets to create was President Nixon’s bunker at NORAD, which was inspired in part by the War Room in Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove.” A member of the crew added an extra layer of serendipity to the sequences shot on this set. Director of photography Larry Fong remembers discussing how the moving, changing maps in the War Room might have been done. “My hunch was projection, others thought it was painted graphics with light bulbs, and then the gaffer said, `Oh, I know how they did that. That was rear projection.’ I had to ask him: `How do you know that?’ And he answered, `Because I was there. I was doing the rear projection.’ It was crazy. What were the chances? There was a lot of experience on this crew.”

Production also took over placeCityVancouver’s former Riverview Hospital, and remade it into the Gila Flats nuclear testing facility where Jon Osterman becomes Dr. Manhattan.

On soundstages at CMPP, McDowell’s team built the production’s largest set, Adrian Veidt’s Antarctic retreat, placeKarnak, where the film’s climax unfolds. They also created Veidt’s palatial office at Veidt Enterprises in the form of a multi-purpose set that could be his interior office if shot from one angle, and his exterior office if shot from another.

Also built on these stages were the interiors for The Comedian’s and Dan Dreiberg’s apartments. The Comedian’s apartment was comprised of three sets: the living room set, where Blake fights off his assassin; a tall platform set with a trick window for visual effects elements; and a bedroom set, with his closet and the secret compartment where he hides his Comedian memorabilia. Additionally, CMPP held the green screen stages for the film’s visual effects sequences.

Veidt inhabits an environment of extravagant materials, in a palette of royal purple and gold, surrounded by priceless artifacts collected from his travels. “With the set design, we wanted to show what Veidt Enterprises is doing in terms of its connection to airlines, toys, and other endeavors,” says McDowell. “Around his office, you can see the Mask action figures, so he is profiting from his friends. We also wanted to infuse the backgrounds with imagery surrounding the Nostalgia perfume that Veidt created. It became one of the ways of insinuating how pervasive his empire is in the culture of 1985.”

“The guys were so good, it got to the point where I just expected a Veidt aspirin bottle to show up, or a pair of Veidt shoes,” Snyder says with a laugh. McDowell confirms that “the shoes did, in fact, appear.”

A soundstage at CMPP also housed the old subway tunnel, which Dan Dreiberg converts into the Owl Chamber. “Dan’s brownstone leads through a secret passageway down into an old, abandoned subway station. We created three sets: the exterior of the apartment, built on the backlot, and, on the stage, the interior of Dan’s home and the Owl Chamber, which houses the Owl Ship,” explains McDowell.

Nite Owl’s Owl Ship, Archimedes (“Archie”)-an engineering marvel that Dan created and once used to combat crime-is one of the indelible elements of Watchmen. McDowell brought together a team of artisans, starting with sculptor and boat builder Jack Gavreau, to bring Archie to life down to the hull scrapes and turbine exhaust ports. “Everyone, from sculptors and painters to set dressing and props, worked in this tiny little space,” McDowell recalls. “But it proved to be one of the most satisfying sets in the movie for us. The idea with the Owl Ship is that form follows function, and everything is there because it has a purpose. In the Owl Chamber, we also incorporated dents and damage where we assumed he crashed while flight testing. It was very important for the audience to believe that this was a real craft, so it’s covered in scratches and scrapes.”

The other multi-purpose location taken over by production was an old paper mill called Domtar, which was large enough to contain Dr. Manhattan’s government lab and apartment. “We built Manhattan’s apartment based on the idea that Manhattan lives in the middle of this industrial space,” McDowell describes. “But we imagined that the government officials had hired the best decorators to design an elaborate living space within the lab, befitting the most important man in the world.”

At the height of shooting, Dave Gibbons visited the set, an experience he found overwhelming. “I was just bowled over by the level of attention to detail,” he attests. “Careful thought had been given to every little corner, even things I had stuck in the artwork that I hadn’t given a second thought to. When you draw something from your imagination, you have this misty impression of a picture that you then try to interpret. This was like seeing that misty picture crystallized into reality.”

Gibbons, who had previously only seen his Owl Ship on paper, had the rare experience of physically exploring his creation. “I looked at the model of the full-size Owl Ship, knocked on it, stood inside it, moved some of the controls,” he marvels. “It was so fantastic for somebody who lives in their imagination a lot of the time to see these things actually become solid in the real world. It was one of the most exciting experiences I’ve had connected with comics.”

Snyder admits he was as nervous as everyone else about Gibbons’s visit to the set. “When Dave arrived, we were all a little bit afraid, but excited at the same time. We loved the book, we loved the images; we cared to make them come to life as much as we could, and to make it respectful. You can show a set to a fan who says, `The Owl Ship looks awesome,’ but it’s another thing entirely when the creator sees it and says, `Wow, you guys loved that, didn’t you?’ That was what we wanted. It was pretty cool.”

The cast was equally inspired by the world within a world they inhabited for a few months over a Vancouver winter. Jeffrey Dean Morgan asserts, “The details of it were just astonishing in their quality, right down to the smallest detail. I’ve never been a part of anything like this in my life. Every day I came onto the set and I was blown away by the scale of it, the work that so many people put into this thing. The novel literally came to life.”

One of the most subversive elements of the novel, which McDowell sought to incorporate into the film, was “the twisting of the conventional primary palette of comic books into the secondary colors. It immediately made the Watchmen series into an incredibly striking package. People had not seen those colors in this medium before. Watchmen had fantastic graphic decisions throughout, from the smiley face cover onward, so that was key for us.”

What would not work on film were the clean lines of a graphic novel. “To embed these characters in the real world, clean lines don’t translate,” the production designer says. “But we found that if we took a grittier, more textured style, then added the strong secondary palette of the graphic novel to it, it became a way to find a common language of stylization.”

Fabricating the Masks

The use of the graphic novel’s color palette extended to costume design as well. “We wanted to be very respectful to the source material, so that affected a lot of our color choices,” notes costume designer Michael Wilkinson. “We used a lot of greens, purples, oranges and browns…the murky secondary colors that darken as the story progresses.”

With the novel spanning several decades-from 1938 to 1985-and with much cutting back and forth between eras, it was essential to choose clothing that was appropriate for each period to make it clear where in the timeline a scene is taking place. The design team settled on “archetypal pieces that really summed up each decade and gave a sense of period authenticity to the movie,” says Wilkinson. While that sounds straightforward, the task was anything but, especially considering there were, at times, more than 300 extras in a scene. “There is a myriad of uniforms in the film-everything from World War II soldiers and sailors, to 1938 NYPD, to Vietnam War uniforms from both sides-and each one had to be meticulously well-researched. Adding to that, we had diner waitresses, prison cooks, security guards, flower children protesting in the 1960s, Soviet soldiers, astronauts and much more. I estimate there must have been about 150,000 pieces in our costume stock. We had a 600-page manifest, down to every last earring, and that’s a lot to wrap your brain around.”

The costumes for the key cast, like their environments, would need to be intimately designed, particularly their crime-fighting outfits. Wilkinson worked with the specialty costume company Quantum FX to create full body casts of all the major characters, upon which they then sculpted the details of each costume in clay. “We could then take those molds and render them in foam latex so you get a stylized physique-wrinkle-free and with beautiful, sculpted details, while being flexible and breathable for the actors,” he says.

For Dreiberg’s Owl costume, Wilkinson and his team researched 1970s aerospace technology to mimic Dan’s knowledge of birds and aerodynamics. “We looked at interesting NASA-style technology, things like exposed zippers, and air vents that might help him move through the air in a smoother way,” the costume designer offers. “At the same time, Zack wanted Nite Owl to be a little fear-inspiring; it’s important that putting on his costume has a very empowering quality. It helps Dan access a side of his personality that’s different from his very shy, retiring daytime character.”

The juxtaposition of daytime personality against the masked vigilante is also quite dynamic in the character of Silk Spectre. Sally Jupiter had created a sexy costume for her teenage daughter, a yellow and black mini-dress only marginally more modest than Sally’s costume had been. Wilkinson updated Laurie’s costume to be a form-fitting latex suit. “We wanted to keep the spirit of the graphic novel intact; Silk Spectre is in the same colors and has the same graphic silhouette as her costume in the book,” Wilkinson explains. “But we rendered it in latex because we liked the idea of that extreme, hyper-sexualized version of her character. It juxtaposes so beautifully with Laurie’s day-to-day look, which is very stitched together, tailored and precise, wanting to be taken seriously. We enjoyed exploring the two different sides of her personality.”

In contrast to the characteristically extreme costumes of the majority of the Masks is the almost non-descript costume of Rorschach: a simple trench coat. “When you read about the character in the graphic novel, he has a very bleak outlook on life,” Wilkinson observes. “He’s very misanthropic. He just wants to bring a little bit of justice in the world. In terms of his costume, there is the sense that he gave up caring about his appearance a long time ago. He just wears this outfit, not to make a particular impression, just because it’s what he wears. He keeps it in a dumpster. It has years of layers of grime and other encrusted crud on it. The whole litany of his past can be read through his trench coat.”

Transforming the Masks

Nevertheless, Rorschach has one of the most striking attributes of all the costumed superheroes: his mask of shifting inkblots. “The evolution of Rorschach’s mask was a long and complex one,” remarks Wilkinson. “We developed a printing process onto a fantastic four-way Lycra that enabled us to create a rough, canvas-like texture but also had a stretchy quality, so we could achieve that smooth, egg-like silhouette. And then the digital effects team created these beautiful moving inkblots on top of the fabric. It was a great collaboration between costumes and visual effects.”

In order to complete the effect of the perpetually morphing inkblot mask-which Rorschach calls his “face”-the lycra was embedded with motion capture markers. “It was covered in tracking dots, except for my eyes,” describes Haley, who dubbed his mask “the sock.” “Even though Rorschach’s eyes aren’t visible under the mask, I was able to see what I was doing. So, the material and the blots move; it’s just absolutely awesome.”

“It was fascinating how Jackie was able to communicate so much emotion through this medium,” comments Deborah Snyder. “The patterns were designed as a reflection of his performance, and it was amazing how much complexity Jackie brought to Rorschach through his voice and body…how the mask became part of him.”

The visual effects team, under the supervision of John “DJ” DesJardin, animated the transitions between the inkblot patterns at different speeds, according to what Snyder wanted for the given scene. “We tried to model his expressions after the ones Dave Gibbons drew for the graphic novel,” DesJardin reveals. “The inkblots are not just black and white; the edges are grey and animated in a way that makes it look like the ink is coming out of the cloth and sinking back in again.”

Snyder and DesJardin engendered a natural collaboration in ensuring the tone of the visual effects would align with the vision the director was creating on the live sets. “The visual effects are a partner in the movie,” says Snyder. “Whether it was extending practical sets or inserting floating blimps in the skyline, or rendering Rorschach’s mask or Dr. Manhattan’s body-those are all things that have to go into the pipeline. And DJ did an amazing job of keeping this massive endeavor down to a very personal, shot-by-shot approach to the movie.”

Beyond visual effects, the embodiment of Dr. Manhattan hinged primarily on the actor playing him. “Dr. Manhattan was the biggest challenge for us,” says Deborah Snyder, “because we had to figure out how to create this god on earth that glows blue light, who can be 100-feet-tall, then shrink down to human size. At the same time, there was a real person playing Dr. Manhattan, through the medium of performance capture. It takes a really disciplined actor to pull that off, and Billy did such a great job.”

Billy Crudup’s performance would provide both the physical and the emotional anchor for the superbeing. Notes Levin, “Manhattan is an amazing, fascinating character, yet I never made the kind of emotional connection to the character in the book as I did watching Billy play him. It was deeply moving. There are so many moments in the film where the material coupled with the cast’s performances resulted in the kind of alchemy that only great actors are able to conjure when bringing a character to life.”

In addition to his physical embodiment, Manhattan has an effect on the environment around him: a blue glow that emanates from his body. “When I read the graphic novel, Manhattan was the only element that made me think, `How do we do this?’” recalls cinematographer Larry Fong.

Together, DesJardin and Fong found a creative solution. “We ultimately made a suit that had all the tracking markers we needed for motion capture but also thousands of LEDs that put out this nice, diffuse, blue light,” DesJardin explains. “Zack’s idea was that when Jon Osterman pulled himself back together, he made this ideal male form for him to embody. So, while keeping Billy’s face and remaining accurate to his performance, we created a CG character with a powerful, ultra-ripped, perfected body.”

Other cast members, however, could not rely on digital effects to alter their physical appearance or to prepare them for the intense action sequences in the film. Instead, they each undertook an individualized training program under the guidance of veteran stunt coordinator Damon Caro and his team.

“We looked at the characters specifically to determine what would be needed for each of their fight scenes, and all of the actors brought so much energy and enthusiasm to the table” says Caro, who had also worked with Snyder on “300.”

Malin Akerman had never done any kind of fight work so, Caro relates, “We pieced together a series of drills for her and she was so game to learn everything.” The actress also worked closely with her stunt double, Bridgett Riley, whose background is in women’s kickboxing and boxing.

“Bridgett trained me so hard, but I loved it,” Akerman states, admitting, “After the first week of training, I was thinking, `What did I get myself into?’ But then it got easier and it was such an amazing experience to learn the fight choreography. It brought out a whole different side of me that I didn’t know was there,” she smiles, “and definitely helped me get more into the character.”

For Rorschach, whose stature belies his strength, Caro offers, “Going in we figured that since Rorschach wears a mask, it would be easiest just to double him. But it turned out that Jackie was so psyched to do it. I looked at his movement and martial arts ability, and it was awesome. We ended up using him a lot.”

Haley adds, “I’ve been working out for a long time, doing different things to stay in shape. When I got this part, I started a new regimen to increase muscle mass and I also started to look at the proper way to eat. It was all about core training, and I started getting results that were off the hook.”

Unlike his partner, Patrick Wilson, as Dan Dreiberg, aka Night Owl II, had to appear alternately mild-mannered and threatening. The actor actually put on a fair amount of weight to reflect the contradiction between his alter egos. “I was in a different place from the other guys because I needed to be in shape to do all this fighting, but I had to gain 25 pounds or so to do the role; there was always an issue of Dan’s weight. I’m a runner but I had to stop doing any sort of cardio. Instead I did weights and more strength training because I needed Dan to be big but a little soft.”

Executive producer Herb Gains remarks, “We put the actors through physical training; aging makeup; wigs; prosthetics; bulky, uncomfortable suits… Everybody had a tremendous amount of pressure put on them and everybody delivered.”

Apart from the cast, the combination of intense action sequences and digital effects, done in such a stylized way, put specific demands on Larry Fong and editor William Hoy. “I tried to get my cues from how Zack wanted to apply his visual style to the film, from the complicated title sequence onward,” says Fong. “The shots he wanted were very precisely designed; they’re very specific, if you look at the storyboards.”

“The whole idea of symmetry plays a big role in the graphic novel, and Zack took that approach in composing shots,” comments Deborah Snyder. “The best way to do that was with a single camera. There’s not a lot of SteadiCam. The action plays out within the shots almost like the frames of a comic panel. It was something we all gave a lot of thought to and worked closely together to achieve.”

Every shot was highly controlled. “There were certain iconic frames that we wanted to stay true to that relate back to the graphic novel,” says Hoy. “These are the images you want to just burn into the viewer’s mind, but not to encroach on what’s happening emotionally among the characters.”

In addition to the characters who are so well known to Watchmen aficionados, the film has glimpses of some famous people of the day. A team of special make-up designers, led by Greg Cannom, created facial prosthetics to bring to life the many historical and celebrity figures that were integral to their respective eras, including Presidents Kennedy and Nixon, and younger versions of Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Annie Leibowitz, and The Village People.

Music also plays a major role in establishing the timeline of the story. Snyder affirms, “Music is really important to me because not only does it set us in a place in time, it has the ability to evoke a flood of images and emotions.”

“Watchmen” features a collection of classic songs from such legendary artists as Nat “King” Cole, Billie Holiday, Simon & Garfunkel, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. In addition, the group My Chemical Romance performs a reinterpretation of the Bob Dylan song “Desolation Row.” The film’s musical score is by composer Tyler Bates.

Snyder asserts, “It’s a history with similarities to the one we all know. The big events-the sounds and sights-are largely the same. It’s the details that are different.”

“All of the different elements of the film made it hugely complex logistically and a colossal endeavor overall. I have to commend Zack, who took the whole thing on his shoulders and never seemed to break a sweat,” says producer Lloyd Levin. “He knows how important Watchmen is to so many people. But he embraced it fully and completely, without any fear.”

Producer Lawrence Gordon agrees, adding, “Perhaps equally as impressive as his exciting vision for the movie was Zack’s ability to remain a nice guy throughout the making of it. And now that the film is finished, I can say it was well worth the wait.”

Deborah Snyder states that everyone involved brought unparalleled passion and commitment to their work in bringing Watchmen to the screen. “Watchmen is not only significant to the comic book community; it has so much significance as a piece of literature. Our hope is that whoever sees the film discovers or rediscovers the graphic novel because there’s so much more than we can possibly get on the screen.”

Zack Snyder reflects, “Watchmen is such a milestone; it was a privilege to direct this film. Deborah and I had so much fun working alongside everyone involved to finally make it happen. For me, the `why’ of this movie is all the small moral questions that lead to a giant moral question, and that question has no real answer. The end of the movie is meant to spark debate. I hope people come out of it thinking about which side of the question they might fall on. The graphic novel makes you question who is a good guy and who is a bad guy, and I hope the movie does the same thing.

“What is it that someone does that makes him a hero, even in real world terms? Those questions aren’t always as cut and dried, or as easy, as they are in movies. I think in the end `Watchmen’ wants to make that really difficult for you. And I think that’s how it should be.”

These production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

Watchmen

Starring: Patrick Wilson, Jackie Earle Haley, Matthew Goode, Billy Crudup, Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Malin Akerman, Carla Gugino, Stephen McHattie, Matt Frewer

Directed by: Zack Snyder

Screenplay by: David Hayter, Alex Tse

Release Date: March 6th, 2009

MPAA Rating: R for graphic violence, sexuality, nudity, language.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $107,509,799 (58.0%)

Foreign: $77,738,261 (42.0%)

Total: $185,248,060 (Worldwide)