Marjane Satrapi’s critically acclaimed memoir, “Persepolis,” comes to life in the witty and heartfelt animated feature directed by Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud.

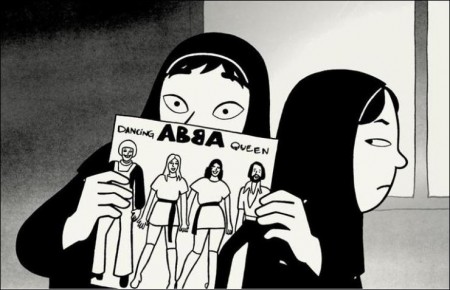

“Persepolis” is the poignant story of a young girl coming-of-age in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. It is through the eyes of precocious and outspoken nine-year-old Marjane that we see a people’s hopes dashed as fundamentalists take power – forcing the veil on women and imprisoning thousands. Clever and fearless, she outsmarts the “social guardians” and discovers punk, ABBA and Iron Maiden. Yet when her uncle is senselessly executed and as bombs fall around Tehran in the Iran / Iraq war the daily fear that permeates life in Iran is palpable.

As she gets older, Marjane’s boldness causes her parents to worry over her continued safety. And so, at age fourteen, they make the difficult decision to send her to school in Austria. Vulnerable and alone in a strange land, she endures the typical ordeals of a teenager. In addition, Marjane has to combat being equated with the religious fundamentalism and extremism she fled her country to escape. Over time, she gains acceptance, and even experiences love, but after high school she finds herself alone and horribly homesick.

Though it means putting on the veil and living in a tyrannical society, Marjane decides to return to Iran to be close to her family. After a difficult period of adjustment, she enters art school and marries, all the while continuing to speak out against the hypocrisy she witnesses. At age 24, she realizes that while she is deeply Iranian, she cannot live in Iran. She then makes the heartbreaking decision to leave her homeland for France, optimistic about her future, shaped indelibly by her past.

Interview with Marjane Satrapi – Director / Author

Did you adapt your graphic novel for the screen because you felt you weren’t finished with this story?

I suppose it’s my collaboration with Vincent (Paronnaud) which made things possible. When the graphic novels were first published, they had immediate success and I got several offers to adapt Persepolis, especially when the books were published in the US. I even got offered projects like a Beverly Hills 90210- type TV show and a movie featuring Jennifer Lopez as my mother and Brad Pitt as my father – things like that! It was just crazy.

To be completely honest, it had been four years since I’d written and drawn Persepolis, I felt the work was finished. It was when I started talking with Vincent about the film project that I realized I not only had the opportunity to work with him, but also the possibility to experience something completely new. After having written graphic novels, children’s books, comic strips for newspapers, murals, etc, I felt that I’d reached a transition period. I didn’t want to make a film all by myself and I felt if I was going to do it with anyone, it should be with Vincent and Vincent alone. He was game for it, and I was excited by the challenge. I thought we’d have fun… Sometimes, it’s the little things that lead to decisions. And I already knew (Producer) Marc- Antoine Robert, it was finally time for us to work together. That was it!

Did you know from the beginning that it was going be an animated feature rather than live-action?

Yes, I think we’d have lost the universal appeal of the storyline. With live-action, it would have turned into a story of people living in a distant land who don’t look like us. At best, it would have been an exotic story, and at worst, a “Third-World” story. The novels have been a worldwide success because the drawings are abstract, black-and-white. I think this helped everybody to relate to it, whether in China, Israel, Chile, or Korea, it’s a universal story. Persepolis has dreamlike moments, the drawings help us to maintain cohesion and consistency, and the black-and-white (I’m always afraid color may turn out to be vulgar) also helped in this respect, as did the abstraction of the setting and location. Vincent and I thought the challenge was all the more interesting for this and an aesthetic standpoint.

What drove you to ask Vincent to share your studio six years ago?

At the time I hadn’t met him. I’d seen his drawings at a friend’s place and thought to myself “you’d have to cut this guy’s fingers off to stop him from drawing!” his work was just fantastic. There is something totally off-the-wall and over-the-top about it, and yet it also has dignity and decency. I’d also seen two short films he’d made with Cizo [Lyonnel Mathieu]: O Boy What Nice Legs and Raging Blues which I liked very much.

How do you complement each other?

When we shared the same studio, we did drawings together. We have different styles but they match so well. We come from totally different countries, cultures and backgrounds, yet we’ve always been on the same wavelength. You could say that together we shattered the notion of “the culture clash”. I’m an outgoing kind of person, he’s rather introverted, but when it comes to drawing, working together, it’s the other way around. When we worked like madmen for three years, we never had a single row, although we were always honest with each other.

Did you have difficulty choosing the material from the four novels you wanted to keep in the movie?

When I was writing the books, I had to remember sixteen years of my life, including things I definitely wanted to forget. It was a very painful process. I dreaded starting the script, and couldn’t have done it on my own. The hardest part was the beginning, and distancing myself from the existing narrative. We had to start from scratch, to create something altogether different but with the same material. It’s a one-of-a-kind piece.There was no point filming a sequence of panels. People generally assume that a graphic novel is like a movie storyboard, which of course is not the case. With graphic novels, the relationship between the writer and reader is participatory. In film, the audience is passive. It involves motion, sound, music, so therefore the narrative’s design and content is very different.

Did you both agree on the look of the film from the very start?

Yes, I guess it could be defined as “stylized realism,” because we wanted the drawing to be completely life-like, not like a cartoon. Therefore, unlike a cartoon, we didn’t have that much of a margin in terms of facial expressions and movement. This was the message which I was determined to convey to designers and animators. I’ve always been obsessed with the post-war film schools of Italian neo-realism and German expressionism and soon understood why. In post-WWI Germany, the economy was so devastated that they couldn’t afford to shoot films on location, and so they were shot in studios using mood and amazing geometrical shapes.

In post-WWII Italy, the same happened, but things turned out the opposite – they shot films in the streets with unknown actors because they had no money. In both schools, you find the kind of hope in people who went through the war and experienced great despair. I am myself a post-war person having lived through the 8 year war between Iraq and Iran. The film is a combination of sorts; of German expressionism and Italian neo-realism. It features very down-to-earth, realistic scenes, and a highly design-oriented approach, with images sometimes bordering on the abstract. We were also influenced by elements of movies we both loved, like the fast pace of Scorsese’s Goodfellas.

When it came to the filmmaking, how did you split the work between you, Vincent and artistic director Marc Jousset?

We needed someone with an overview, someone who could control all stages of the filmmaking process. Vincent suggested Marc Jousset because he’d worked with him on Raging Blues. Marc was the only one who understood what we wanted to do. I wrote the plot and Vincent and I wrote and discussed the shooting of the script. Vincent then took care of the production design, the actual shooting, the props, the characters, and what was going on within each scene. However, we all had a say on every stage of the filmmaking. Now I can barely tell where his work begins and where mine ends and visa versa. We complemented each other so to speak.

This is an animated film with a lot of characters… 600 different characters altogether! It’s unusual to have so many! I drew them all, their fronts and their profiles. Afterwards, the designers and animators drew them from every angle developing their facial expressions and motions. To help them out, I was filmed acting out the scenes. It was the key to keeping the emotion intact, and finding the right balance between sobriety and fantasy. I also had the dreadful job of choreographing the “Eye of the Tiger” scene…

Was it hard for you to see other designers reinterpret your drawing and also drawing your face constantly?

It’s a peculiar feeling. Your drawing is like your baby, and all of a sudden, it belongs to everybody! They didn’t only reinterpret my drawings and my characters, but my face and life story. Unlike Vincent, I had always worked on my own. I even had my own corner in the studio, so you can imagine how I felt when I saw my face everywhere, In small, medium and large, as a little girl, a teenager, a young girl, a grown-up, front, back, profile, laughing, vomiting, crying etc. It was just unbearable! I had to say to myself “it’s just a character.” It was the same for the other characters because their stories are also real.

My grandmother of course, actually existed and lived and died, as had my uncle. I couldn’t let emotion get in the way, or else it would have become intolerable for everyone. If they’d seen me with tears in my eyes, they wouldn’t have been able to continue with their work. We needed them to feel free so that they could do their best, so I had no choice but to talk about myself and the people in my life as fictional characters: “Marjane does this, her grandmother’s like that…” otherwise it would have been impossible. This doesn’t mean that at times I wasn’t overwhelmed by emotion, (notably the time when the designers were drawing my parents). It was only after the script was written that this story became fiction and went public. It wasn’t exactly me anymore, and yet, paradoxically, it was still me…

Why did you choose Chiara Mastroianni for “your” voice?

We wanted to record the voices prior to the shoot so that the animation, motions and facial expressions could match the actors’ dialogue and acting. The first name we thought of was Danielle Darrieux’s as my grandmother. She was the only one who could do it justice; she’s funny, intelligent and full of wit and sass. She loves to have fun and doesn’t shy away from absurd situations. I’ll always treasure the time we spent recording her voice. I dreamed of Catherine Deneuve for my mother’s voice. Back in Iran, the two most famous French actors at the time were Catherine Deneuve and Alain Delon. She was perfect for the part. When she was Chief Editor of Vogue, she picked twenty artists to work on the issue, including me. I was so proud. When I asked her to lend her voice, she said yes right away. I must say I was impressed when I directed and played opposite her. At some point in the script, I was supposed to say: “Women like you – I just want to fuck them against the wall and throw them in the trash!”

Fortunately it became easier after gulping down a few glasses of cognac! It was only after I picked Chiara that I realized I was adding a new chapter to a glamorous film mythology, as they’d already played mother and daughter on several occasions. As far as Chiara was concerned, she had actually heard about the film through her mother, and called me to do a voice test, after which we immediately connected. I loved her voice, her talent, her personality, her generosity. We worked hard and rehearsed for two months… She’s a workaholic and perfectionist, like Vincent and myself. She followed every step of the filmmaking process and often dropped by the studio to visit us.

What was the most memorable moment of the whole experience?

The first screening for the whole team in a theatre on the Champs-Elysées. At the end, I was crying, and so was the whole audience. Iran is still in the headlines today. Even though you want the film to be universal, you can’t stop people from seeing it in this light… True. Although in my eyes the most exotic section takes place in Vienna. The film is not judgmental, it doesn’t say, “this is right and that is wrong” it just shows that the situation has many layers. This isn’t a politically oriented film with a message to sell. It is first and foremost a film about my love for my family. However, if Western audiences end up considering Iranians as human beings just like the rest of us, and not as abstract notions like

– “Islamic fundamentalists”, “terrorists”, or the “Axis of Evil”, then I’ll feel like I’ve done something. Don’t forget that the first victims of fundamentalism are the Iranians themselves.

Do you miss Iran?

Of course. It’s my homeland and always will be. If I were a man, I’d say France is my wife, but Iran is my first love and will always linger with me. Obviously, I can’t forget all those years when I’d wake up with a view of an 18,700-foot high, snowcovered mountain that dominated Tehran and my life…

It’s hard to think that I’ll never be able to see it anymore. I miss it. Then again, I have the life I wanted. I live in Paris, which is one of the most beautiful cities in the world, with the man I love, doing the job I like – plus, I get paid to do what I like to do. Out of respect for those who have stayed there, who share my ideas but cannot express them, I’d find it inappropriate and distasteful to be complaining. If I had given in to despair, everything would have been lost. So up until the last moment, I’ll hold my head high and keep laughing because they won’t get the best of me. As long as you’re alive you can protest and shout, yet laughter is the most subversive weapon of all.

Interview with Vincent Paronnaud – Director

Do you remember your first meeting with Marjane Satrapi?

Six years ago she asked me to share her design studio. I had heard of Marjane, as she was beginning to get a name for herself. I was a bit wary at first, but I reluctantly accepted her offer.

Why?

I’m distrustful by nature! What’s more, when she rang me up, although we had never met or talked, she sounded overly enthusiastic!

What had your career been like until then?

After dropping out of school at 17, I dabbled in quite a few things; drawing, music, etc… I began publishing graphic novels [under the penname Winshluss], writing serial storyboards and working on animated shorts.

When you read the Persepolis novels, what was your reaction?

Amazed. I was in the studio when Marjane was completing the second volume. In the beginning, I was afraid of her ethnic ” Not Without My Daughter” style, and of the girly comic aspect, which, according to the media, characterized Marjane’s work. It was in fact, just the opposite; I was swept off my feet. Her work has a strong, genuine power; the content is as valuable as the design, and it combines humor and emotion, which is quite rare.

Do you remember when she first asked you to make an animated feature based on the Persepolis books?

When Marc-Antoine Robert offered to produce Persepolis, she asked me to make the film with her. She was reassured because I had already directed black and white animated shorts. I couldn’t refuse, I loved the book, and I loved Marjane. It was a wonderful opportunity for me to do something I had never done before, to work on such an artistically challenging project. It was both appealing and risky.

What sources did you draw upon when you started to think of the film?

We knew we had to keep the energy of the novels. We couldn’t be content with filming one panel after another. In fact our sources were live-action films. I had seen a lot of Italian comedies because my mother loved them. Marjane is very fond of Murnau and German expressionism, so we drew our inspiration from that and then put together what we both liked. Marjane’s book is about family life, so the film was going to be based on a central family theme also. The usual codes in animation didn’t seem to fit, so I used movie-style editing, with a great many jump-cuts. Even from an aesthetic viewpoint, we drew our sources from cinematic techniques.

Did you watch films together before starting to work on Persepolis?

I did watch a few films like The Night Of The Hunter and Touch of Evil, and some action films like Duel which taught me a lot about editing.

When films are well-made, whatever the genre, there are always things to learn. More specifically, how did you manage to write the script together?

For three months, we met everyday for three to four hours. Neither of us can type, so we used a pencil because it can be erased. We’d read what had been written, crossing out, rewriting, cutting, etc… We had to strike the right balance between the crucial moments and the insignificant details of everyday life; it was hard to choose what had to be kept and what to leave out. After a while we forgot about the book and worked on the script.

Unlike the books, the film is a long flashback. How did you come up with the idea of the opening scene in color?

Marjane had told me that one Friday (Friday is the day for flights to Tehran), she was feeling so low that she went to the airport with the intention of leaving. She spent the whole day there, crying and watching the planes taking off. We thought it would be a great opening scene. It conveys a sense of distance, of nostalgia for the story. It was all the more obvious as the film was about exile…

What do you think of her wish to deal with the story again, from a different artistic approach?

Apart from the artistic challenge, Marjane is leading a fight, so naturally she wanted to make it into a film. But she’s a demanding person, with an honest intellectual purpose. It’s rare to find autobiographical books like Persepolis, written with such modesty, and such little self-indulgence. She wants to make a statement, and hopes for people to get a different view from the one they watch on TV or read in the papers. Furthermore, she wants to address the meaning of exile, and what it means for a young girl to be thrown into the midst of historic events that she cannot comprehend…

Given the personal, autobiographical aspect of Persepolis, was it hard to find your place when you were writing the script?

It was not only hard, it was horrendous! Tinkering with somebody else’s work is difficult but this was also somebody’s life. Somebody sitting opposite me, somebody I know and love. I could see it was affecting Marjane, so I had to tread carefully, but she was extremely encouraging. The same for the visual aspect of the film; artistically speaking, she gave me free rein. We complemented each other, and there was always a moment when you needed the other’s viewpoint or opinion.

What were your main concerns when you started making the film?

As Marjane’s characters couldn’t be anything but sheer black and white, we focused on the production design. As we couldn’t have a black or white background we had to start from scratch. I used pictures of Tehran and Vienna to as inspiration, without being totally dependent on them, and integrated various grey shades. At the same time we had to bear in mind not to soften the graphic strength of Marjane’s universe. We focused on fluent lines, talked a lot with Marc Jousset, and finally came up with a classic design.

As time went by, what was the most difficult hurdle to clear?

Keeping the enthusiasm going. Being under pressure for nearly three years, and trying to sustain our overall vision of the project was difficult. Marjane and I had a rather atypical approach to the codes, and even the work habits of animation. Marc-Antoine knew exactly what we wanted and he had been fighting hard on our behalf. So had Stéphane Roche who was in charge of the compositing.1 Nothing was ever definitive. We were constantly changing things, testing new ideas, relentlessly improving what had been done. To keep things moving along, a lot of people helped us carry out our project because they understood our goal. The big plus was that everything was within reach at the one point where we worked all together in the studio. If I needed to change something I just went to the office next door and told the person in charge of the sequence. Even if it doesn’t sound very original, I think human relationships are key when you make a film.

What surprised you most during the making of the film?

First and foremost, Marjane and I never had a row, despite there being a lot of stress. Marjane was under a great deal of strain. People didn’t notice, because she’s so enthusiastic and so full of passion and energy, while I’m a bit of a pain in the ass! Marjane has often told me that. Nothing is ever quite right for me. That’s the way I am. What also surprised me was the way I became emotionally involved. I used to think I was rather detached from the subject matter of my work, but there was something so intrinsically emotional about this story. Marjane manages at once to convey these emotions and to remain modest. I wonder how she does it.

Why did you pick Olivier Bernet to write the score?

We understood what we wanted and he was there with us from the very beginning. I even changed some images in accordance with his suggestions. In Persepolis, music plays a crucial role; it connects the sequences and gives unity to the film.

What particular memory will stay with you from this experience?

Perhaps the first screening of the rough cut. Marjane was sweating, and nearly passed out when she saw herself on screen. She tries hard to forget it’s her life being told. It’s better that she forgets, otherwise it would be unbearable, both for her and me.

Interview with Chiara Mastroianni — Voice of Marjane as Teenager and Young Adult

You called Marjane Satrapi to be part of Persepolis…

Yes. I had read all four Persepolis novels and loved them. The combination of design, humor, hindsight and self-mockery, with no trace of self-indulgence or victimization was irresistible. I’d been thinking about doing a voice in an animated feature for quite some time, so when my mother mentioned Persepolis to me, I called Marjane and asked to do a voice test.

How did you first meet?

We met at my place. At the time, her voicemail message was quite off putting. I thought “Considering all she’s been through, she must be very tough!” When I saw her large glasses and her smile, I thought there was something punkish about her, and I knew we’d get along fine. I’d only thought about Marjane’s adult voice, but she told me she wanted the same person to do Marjane as a teenager. All the more reason to do the tests! I became even more afraid when I realized I had to do the voice-over with no visual back-up. We worked together and then did a recording session. Thankfully, she found my voice convincing enough to carry on with me. During rehearsal we tried to hone my voice, to make it sound more subtle and rich.

Was it stressful or inspiring playing Marjane?

Both! At the beginning, it was a bit stressful. I imagine it must have been strange for her too after having written the books by herself, she suddenly finds strangers interfering with her work. I could tell that certain scenes reminded her of emotional memories, and sometimes I found that testing. Yet, I think she toned them down, both in the books and in the film.

When we recorded the last scene with her grandmother, (where she tells of how she put Jasmine flowers in her bra), the atmosphere in the studio was wholly different to when we did the scene at school where she meant to beat up the little boy! When you spend time with her, you realize she’s vibrant, yet demanding and decent. She was wonderful in easing the tension and the embarrassment you naturally feel when you’re playing her life out in front of her. This was truly inspiring. When heavy moments came, she’d shrug them off with dirty jokes. It was very helpful to be around Marjane between the first and second recording sessions to get a better sense of who she was.

What impressed you the most about her?

Her freedom. She’s not caught up in conventions; she went through so much at a very early age and remains insatiable. She’s always eager to learn, and never lectures you. With Marjane, I had the feeling of being a teenager again, but at the same time, she’s undoubtedly wise. It’s an interesting combination. When she’s fond of you, she showers you with affection and attention, yet, she has clear-cut ideas about what she wants. She’s afraid of nothing and is a real go-getter. She’s like a magnet both in life and in work.

What was the funniest part of the recording?

Recording the theme “Eye of the Tiger” from Rocky. Marjane asked me to sing it out of tune. I asked her to sing it first, and we both broke loose and had a lot of fun.

What was the most difficult part?

Finding the right tone and rhythm for the voice-over. The scenes with dialogue weren’t a problem, it was the narrating that was more difficult. It was a really different skill, and was hard with no back up. This was the part we worked on most, as soon as the footage was available, as I wanted to be able to hone my voice to match the pace of the scenes better.

Do you remember the first time you met Vincent?

Not exactly, but it had to be at the studio. He’s a shy guy who needs to be won over. At the beginning, he was a bit wary of me, however, it only strengthened my determination to do the voice tests. In the end, his misgivings helped me do a good job. When he was eventually convinced, I knew for a fact it was for good reason. I like Vincent’s hard-boiled personality. I believe they make a great team together because they’re on equal footing. He has a strong sense of propriety too. I looked for Vincent Paronnaud’s graphic novels everywhere, but they were nowhere to be found! It took me weeks before I found out his penname was Winshluss…

How complementary are they?

They couldn’t have managed without each other on this film. They were totally inseparable. They made all the decisions together. They have admiration and respect for each other and are true friends. They’re both very demanding, but for good reasons. Ego is never an issue, all that matters is the film. For the rest of us, nothing could have been more inspiring than such freedom and rigor. Marjane and Vincent wanted to make Persepolis in an “old-fashioned” way, based on actual drawings and not computer images. For all of us, it turned into an amazing challenge, both artistically and professionally.

Your mother has often portrayed Danielle Darrieux’s daughter, but it was the first time you played her granddaughter…

Yes, I liked the idea. The funny thing is, I played opposite Danielle again soon after — on Pascal Thomas’ L’Heure Zero. That was when we really got to know each other. She’s stunning. I can understand why Marjane wanted to work with her. There’s a connection between them. Danielle also has a strong sense of self-mockery and propriety. There’s a spark in her eyes, and she always has a positive and inquisitive approach to others.

What memory of Marjane and Vincent will stay with you?

It was definitely the time when we were recording the voices in the studio with Marc, Stéphane and Denis. They were all working on snippets of dialogue and on the sound effects. Marjane was playing around touching the sound effects console and playing with the props. I also remember Marjane and Vincent having fun making short, crazy films on their cell phones! They looked like whizkids cooking something up!

Interview with Catherine Deneuve — Marjane’s Mother

How did you find out about Marjane Satrapi?

I read her comic strip a while back in Libération. Then I read all four Persepolis novels which I just loved. I like her graphic black and white visuals and the way she uses them, it’s totally surreal and realistic at the same time. I like her spirit. I like her freedom. I like her story which she tells with wistfulness, humor, self-mockery and emotion. The freshness, ambition and success of her work, as well as the strong statement she makes, reminded me of Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Anyway, it’s a unique graphic novel. I loved it so much, I even said in a newspaper that Marjane was my favorite fiction writer. When I was asked by Vogue magazine to act as Chief Editor for a special issue three years ago, I asked her to come on board. She did a wholly unconventional one-page comic strip which I found hilarious.

Do you remember the first time you met?

We had a cup of coffee together, and I noticed that she smoked as much as me! She’s a wonderful person, bright and very funny. I love her oriental charm and her sweetness that’s tinged with self-mockery. She’s both very cheerful and deep. Her take on life is very particular. When she asked me to be her mother’s voice in the film, I instantly said yes because it was her and because I’d wanted to do a voice for an animated feature for a long time.

Can you tell me about the recording?

Marjane’s script was terrific. It was not only very true to the books, but it also included a genuinely cinematic narrative. We met at the studio, and she played and directed opposite me. She was always there for me, paying close attention. She was very specific, yet gave me a great deal of freedom playing the scenes with no visual back-up or specific schedule.

What is your take on the mother’s character?

She’s just like every other mother dealing with their teenage daughter, facing life and its challenges. She’s understanding, caring and concerned. Persepolis also adds a new chapter to a film tradition as I once again play Danielle Darrieux’s daughter. It’s now become inevitable, and Chiara plays my own daughter!

What memory of Marjane Satrapi will stay with you?

She’s a smooth talker. She says one thing with her voice and something different with her eyes…

Interview with Danielle Darrieux — Marjane’s Grandmother

Were you surprised when Marjane Satrapi called you to be the grandmother’s voice in Persepolis?

Yes, nobody had ever asked me to do something like this before. When Marjane came to tell me about her project, I was immediately won over by her energy, her good nature, her wide eyes… She explained that she wanted to record the voices before she started work on the drawings, so that our acting could match the characters’ expressions. She had dreamed I would play her grandmother, Catherine Deneuve her mother and Chiara Mastroianni herself. I liked the idea and said yes right away.

Did she ask you to read the script?

No, but she gave me the books which I devoured and loved! I like her drawing, her characters’ expressions, the way she plays graphically, say, with the headscarves and the way she draws herself with a mole, which she beautifully makes fun of. Her story has the gift of making people laugh and cry. What she’s been through is terrifying. When you’ve gone through so much and can still laugh about it, that’s really unique. That’s probably what gives her that wide eyed look of kindness, energy, and consideration.

What moves you about the grandmother?

She’s an uninhibited character, who’s not afraid of anything. She’s politically incorrect and a straight talker. I love talking dirty, so I felt really comfortable with the character! What moved me most was the kindness with which Marjane described her. Quite obviously, her grandmother meant a lot to her.

How did you want to play the part?

Just as Marjane describes her in her books. Not any differently. When you have a writer that writes so movingly and inspiringly, all you have to do is act. She is definitely a writer through and through.

Can you tell me about the recording?

I recorded my voice before the other actors. When I came to the studio, I’d only read her books, so I knew more or less what it was about, but hadn’t yet been given a script. Marjane sat next to me and before each take, she’d brief me on the situation, giving me my lines and playing opposite me to stand in for the other roles. I don’t like rehearsing much, usually going by instinct, so with Marjane I enjoyed relying on that immensely. Marjane knew exactly what she wanted, I readily did what she asked, and it went very quickly. Later, Marjane and her producers showed me a short excerpt of the film, when I saw the grandmother’s face and heard my voice. It was an odd feeling, but I was really surprised. I thought it matched perfectly!

You once again play Catherine Deneuve’s mother…

It’s become a regular thing to play mother and daughter, although we don’t look that much alike. What may bring us together is our way of handling drama in a light-hearted fashion. Her voice remains calm, she doesn’t indulge in saccharine expressiveness. Her acting is both deep and light-hearted. Her voice and her eyes are so expressive. The three of us have been building a kind of film mythology, passed down through generations. After PERSEPOLIS, where Chiara plays my granddaughter, we were reunited for Pascal Thomas’ upcoming film. I got to know her better and I’ve grown very fond of her.

What memory of Marjane will stay with you?

I once asked her to meet me in a hotel room. It so happened that there were bars on the window. When she left, I thought it would be fun to say goodbye from behind the bars. It felt like a scene from Persepolis. We both had a great laugh.

Interviews by Jean-Pierre Lavoignat, March-April 2007.

Production notes provided by Sony Pictures Classics.

Persepolis

Starring: Sean Penn, Gena Rowlands, Catherine Deneuve, Iggy Pop, Chiara Mastroianni

Directed by: Marjane Satrapi

Screenplay by: Marjane Satrapi

Release: December 25, 2007

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for mature thematic material including violent images, sexual references, language and brief drug content.

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $4,445,756 (19.6%)

Foreign: $18,273,867 (80.4%)

Total: $22,719,623 (Worldwide)