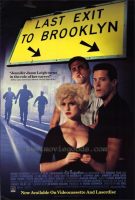

Last Exit to Brooklyn movie storyline. Taken from Hubert Selby, Jr.’s controversial novel set in early 1950s Brooklyn. During a bitter strike by workers against a local factory, a gallery of struggling characters are crushed by their squalid surroundings and selves: an unhappily married union strike leader discovers he is gay; a jaded prostitute falls in love with one of her clients, a naive young sailor; a union negotiator attempts to peacefully resolve the strike while desperately hiding the fact that he’s a communist ; the family of a striking factory worker cannot cope with the fact that their teenage daughter is illegitimately pregnant.

Last Exit to Brooklyn is a 1989 German-British drama film directed by Uli Edel and adapted by Desmond Nakano from Hubert Selby Jr.’s novel of the same name. Starring are Jennifer Jason Leigh, Stephen Lang, Burt Young, Peter Dobson, Jerry Orbach, Stephen Baldwin, Maia Danziger, Sam Rockwell, Camille Saviola, Ricki Lake and Rutanya Alda.

There had been several attempts to adapt Last Exit to Brooklyn into a film prior to this version. One of the earliest attempts was made by producer Steve Krantz and animator Ralph Bakshi, who wanted to direct a live-action film based on the novel. Bakshi had sought out the rights to the novel after completing Heavy Traffic, a film which shared many themes with Selby’s novel. Selby agreed to the adaptation, and actor Robert De Niro accepted the role of Harry in Strike.

According to Bakshi, “the whole thing fell apart when Krantz and I had a falling out over past business. It was a disappointment to me and Selby. Selby and I tried a few other screenplays after that on other subjects, but I could not shake Last Exit from my mind.” Some scenes for the film were shot at Montero’s Bar and Grill, which was owned by Pilar Montero and her husband.

Film Review for Last Exit to Brooklyn

Love stories are about people who find love in happy times. Tragedies are about people who seek love in unhappy times. “Last Exit to Brooklyn” makes a point of taking place in the early 1950s, when all of the escape routes had been cut off for its major characters. The union official cannot admit to being left wing. The strike leader cannot reveal he is homosexual.

The father cannot express his love for his child, the prostitute cannot accept her love for the sailor, and the drag queen is not able to love himself. There isn’t even any music to release these characters – rock ‘n’ roll is still in the future, and the pop ballads of the era mock the passions of everyday life. The characters drink and some of them do drugs, but they don’t get high – they simply find the occasional release of oblivion.

The movie takes place in one of the gloomiest and most depressing urban settings I’ve seen in a movie. These streets aren’t mean, they’re unforgiving. Vast blank warehouse walls loom over the barren pavements, and vacant lots are filled with abandoned cars where mockeries of love take place. When Hubert Selby Jr. wrote the book that inspired this movie 25 years ago, it was attacked in some quarters as pornographic, but it failed the essential test: It didn’t arouse prurient interest, only sadness and despair.

Why do I respond so strongly to movies like this – and “Barfly,” “Taxi Driver,” “The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover” and “Christiane F.,” which was the previous film by the makers of “Last Exit to Brooklyn”? Most people hate movies like this. I think perhaps it is because no attempt is being made to force the characters and stories into comforting endings. The movies don’t let me off the hook.

These are fellow human beings who suffer, who are limited in their freedom to imagine greater happiness for themselves, and yet in their very misery they embody human striving. There is more of humanity in a prostitute trying to truly love, if only for a moment, than in all of the slow-motion romantic fantasies in the world.

The movie takes place in a Brooklyn neighborhood torn by a bitter strike; most of the men work at the factory, and are unemployed by the dispute, but for Harry Black (Stephen Lang), a worker who has been hired to run the strike office, these are good times. He has an expense account to stock kegs of beer in the office, he has a telephone, and best of all he has an excuse to spend long hours away from the wife he does not love or understand. He is a homosexual, and he doesn’t understand that, either, but strange feelings fill him when the neighborhood drag queen sashays by.

One of the striking workers is Big Joe (Burt Young), whose daughter (Ricki Lake) is pregnant. “She ain’t pregnant – she’s just fat!” Big Joe insists even in the eighth month, and yet when he discovers it is true he finds it his duty to beat up the responsible boy – beat him up, and then embrace him as a future son-in-law, and then beat him up some more at the wedding. He accepts the boy as his daughter’s husband, and so the beatings are not really intended as hostile acts, you understand – just the price you have to pay in pain for the freedom of sex.

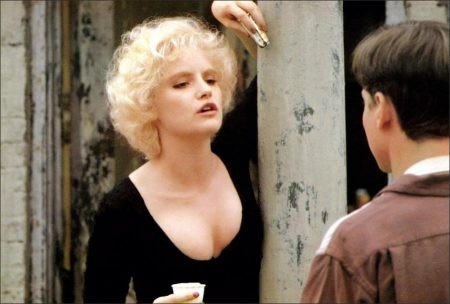

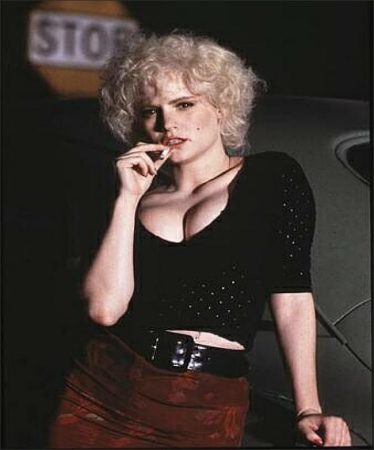

Sex and pain are linked throughout the movie. When Tralala (Jennifer Jason Leigh), the local prostitute, lures the boys from the Brooklyn naval yard into the vacant lots where she works, it’s not for sex – it’s so neighborhood guys can mug the young draftees and roll them. Tralala gets beaten up a lot, too, both physically and mentally.

She has been witness to so many loveless acts of sex that her own body is a thing apart. “I’ve got the best boobs in the West,” she cries, as if they were not a part of her but some kind of award she won in a contest. When one sailor takes her seriously and falls for her, she moves into a Manhattan hotel with him for a few days’ mockery of a real relationship. He’s naive enough to believe it’s love. She’s almost sad enough.

But love and sex do not connect in this movie. When Harry Black, the strike leader, finally admits he is gay and expresses his love for the drag queen, he finds, as the sailor does, that the person he loves cares only for money. Eventually both Harry and Tralala end up in vacant lots, brutally punished, because of sex. The only difference is that Harry is attacked because he tries to have sex, and Tralala is punished through sex – through a horrifying gang rape.

Is there any love in this movie? Yes, in a sense. There is a rather simple-minded boy who wanders through the film, and idealizes Tralala and yearns after her in a goofy way, but she doesn’t know what to do about him. How do you explain to an admirer that his love is misplaced – that really you don’t deserve it? The performances are strong, true, and not a little courageous.

One of the best is by Jerry Orbach (the Mafioso brother in “Crimes and Misdemeanors”) who plays a union leader. At a time when McCarthyism is rampant and strikes are seen as a symptom of communist agitation, he tries to handle hotheads on both sides, and there is the sense that he is successful partly because he sticks to business; his personality doesn’t have a sexual component.

Last Exit to Brooklyn was banned as a book and resulted in several obscenity cases in both the United States and England. Remembering the book and now looking at the movie, I wonder what really upset people: Was it the sex, or just the lovelessness? The drugs, or just the despair? The violence, or its pointlessness? Don’t most books prosecuted for sexual obscenity celebrate sex? This one argues that it’s not worth the trouble – that you’ll end up by breaking your heart.

Last Exit to Brooklyn (1989)

Directed by: Uli Edel

Starring: Jennifer Jason Leigh, Stephen Lang, Burt Young, Peter Dobson, Jerry Orbach, Stephen Baldwin, Maia Danziger, Sam Rockwell, Camille Saviola, Ricki Lake, Rutanya Alda

Screenplay by: Desmond Nakano

Production Design by: David Chapman

Cinematography by: Stefan Czapsky

Film Editing by: Peter Przygodda

Costume Design by: Carol Oditz

Set Decoration by: Leslie A. Pope

Art Direction by: Mark Haack

Music by: Mark Knopfler

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Neue Constantin Film

Release Date: October 12, 1989

Visits: 100