The prime difficulty in most city planning until the 20th century was due to the fact that too few trained individuals had given specific thought to such problems as the regulation of traffic, control of the ingress of food stuffs, and the elimination of waste material. No one had considered the city as a greatly magnified human being which needed light, air, and exercise, as well as protection from the smoke and noise of the machine.

As cities simply grew, with the great concentration of population in the slums and with the advent of the skyscrapers, daily drawing their thousands of occupants from suburban areas, the problems of congestion and health control eventually forced the architects to think in terms of the efficiently planned metropolis. In the 20th century, a few enlightened industrialists also began to perceive that well-housed, healthy workers are a necessary part of the long-range planning for a stable industrial civilization.

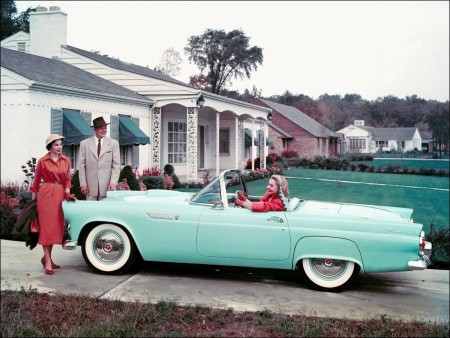

In the America of the 1950s, it has been said, “each householder was able to have his own little Versailles along a cul-de-sac”. For the first time, many middle-class American families could afford to buy their own house, set in its own plot of land with an integrated garage.

The growth of suburban living brought with it a new lifestyle, in which leisure took on a new significance. A wide range of new domestic artefacts appeared as symboIs of this “affluent society”.

Desire for the new lifestyle goods was created and communicated by the mass media in magazine and television advertisements. As well as the readily available mass-produced additions to the household there was a growing tendency in interior decoration for householders to “do-it-yourself” to achieve a luxurious “modern” interior at a fraction of the price which it would cost to bring in an interior decorator.

The suburban “dream house” had its roots in Iate 19th-century America: Frank Lloyd Wright’s turn-of-the-century “Prairie” houses provided a model for later developers to emulate. By the early postwar years the “dream” had been made available to a new sector of the American populationý through improved methods of building cheap standardized, pre-fabricated houses and mortgage schemes provided for former members of the armed forces. A major justification for suburbia was the fact that it was safe for the children of the postwar baby boom. lncreased automobile ownership also helped to make suburban living a practical proposition.

The kitchen was the most important room in the suburban home of the 1950s as appliances began to take over from the automobile as the prime symbols of living in the modem age. The automatic washing-machine, the deep-freeze and the dishwasher were essentially products of the postwar era. They faciIitated living in the new settingý provided consumers with the latest technology in their own homes and filled the ever expanding space that constituted the kitchen area in the new suburban house.

Hostess Housewife: For the American housewife of the 1950s the “fridge” constituted an important status symbol. The kitchen became a living space for the whole family – a place for entertainment as well as a practical working environment. It no longer resembled the all-white “laboratory” of the interwar period. Color and decoration were introduced to the postwar “live-in” kitchen. This dramatic change coincided with, and indeed helped form the new role for the suburban housewife as “glamorous hostess” rather than mere servant substitute.

By 1950 Frigidaire were manufacturing a refrigerator and an electric range, created by Raymond Loewy, boasting details owing their origins to the world of automotive styling. The refrigerator handle operated on a press-button principle which had first been introduced in automobile design and the control panel on the back of the range had much in common with the complex chrome-finished console of a highly styled automobile.

This evocative, transportation and technology linked imagery disappeared at the end of the decade, when a more minimal, angled “sheer look” was introduced, allowing appliances a much more integrated and anonymous role within the general kitchen environment. Appliances ceased to be free-standing monoliths dominating the space around them and became instead elements within the new, increasingly efficient, modem kitchen.

One explanation for the move towards color and decoration in the mid-fifties, American kitchen was the need for personalization within what were standardized suburban environments. Property developers attempted to inject a degree of variation into these pre-fabricated homes, but inevitably there was a high degree of similarity among them, and the inclusion of colour and pattern – albeit within the limited range of those suggested by such magazines as Ladies’ Home Journal or Good Housekeeping, and those supplied by the appliance and plastic laminate manufacturers – went same way towards providing a necessary degree of individualization.

Since each community represents a tremendous capital investment owned by countless individuals, many of whom will be affected adversely by any change proposed, the problem of city planning in the towns already built becomes primarily one of a social and political nature. New laws must be passed enabling local governments to condemn unsafe and unsanitary areas.

New funds must be voted to buy land on which to construct high-speed roadways or the necessary parks to accommodate great populations. The chief problems of city planning for the latter half of the 20th century continue to be those of slum clearance, adequate housing for the lower salaried classes, more rapid and efficient means of communication for traffic and commodities, and the making available of adequate healthy recreational centers for anemic city dwellers.

The practical city, of necessity, looks well. The grouping or zoning of the city’s various functions necessitates that those buildings which have to do with government and the commercial life be arranged in the center, like the medieval Rathäuser and the guildhalls. From this center the brain of the city can most easily control the industrial and transportational developments that connect it with the outside world. Naturally, the problems differ somewhat between seaport and inland towns. Residential facilities must be regulated by the presence or absence of nuisance factors, such as smoke, noise, and poisonous fumes, connected with the city’s industrial plants.

Related Link: View more Popular Culture stories

Views: 384