As much as Weiss’s death is a mystery, its location is even more baffling. Miles from nowhere. No tracks, no maps, no gear. What was he doing way out here? A murder victim is the last thing Stetko expected to find after two years of arduous but uneventful duty, and certainly the last thing she wants to deal with now. Nevertheless, passing him off to the nearest U.S. authorities at McMurdo Station 900 miles away is not an option. Kate Beckinsale, who stars as Marshal Stetko, understands her position. “She realizes that this man needs her to figure out what happened to him. Like it or not, her sense of responsibility and her law enforcement instincts take over and she’s in.”

Unfortunately for a woman whose bags are already packed, this doesn’t look like the kind of case that can be wrapped up easily. Instead, it becomes immediately more complex as Stetko turns her attention to the two remaining members of Weiss’s team, men who could be either prime suspects or the next victims of a killer whose motivation she has yet to discover.

Meanwhile, amplifying the tension is the extreme weather, says Silver. “You feel the raw force of Antarctica impose itself as an ever-present character in the story. Things are more intense when every move you make is potentially fatal. Even investigating a crime scene is a more dangerous proposition here than it would be anywhere else—the transportation, the exposure, the possibility of being stranded. You take a risk every time you step outside.”

“Though it’s part of our world, it looks like it could be outer space,” producer Susan Downey attests, noting that sub-zero temperatures at the South Pole “can drop lower than numbers recorded on equatorial Mars. With this as our setting, it allowed us to put images onto the screen that have never been seen before in this genre, like the whiteout sequences, which are really dynamic, the aerial photography of the base or the Twin Otter coming in for a landing in weather that’s already getting too choppy to support a plane.”

Once the filmmakers committed to depict Antarctica, Downey confirms, they were explicit in their intent. “We wanted to lay out clearly what the temperatures are, how quickly a person can get frostbite or die from exposure. It’s all there and it’s all true.”

The producers selected Manitoba, Canada, to represent exteriors of the frozen Pole; a location frigid enough to give cast and crew a feel for this element of the story and a genuine respect for the whiteout, a natural phenomenon that can literally steal your senses. Says Beckinsale, “There were times when I looked out and couldn’t distinguish where the land and the sky met; it was just one huge whiteness. Totally disorienting. It’s easy to imagine how scary that would be if you were alone. You could turn away from your camp for a moment and not find your way back.”

“Antarctica will kill you. The elements alone tell us we don’t belong there, and ‘Whiteout’ demonstrates this dramatically,” states producer David Gambino. That assessment is born out by the extensive research of Greg Rucka, who, with Steve Lieber, created the original Eisner Award-nominated graphic novel Whiteout on which the film is based, and also served as an executive producer. Declaring the continent “a desert without sand,” Rucka says, “environment as a character intrigues me. So much of what we do and who we are is a direct result of the physical situation we’re in. Antarctica has its own beauty. It’s spectacular, but terrifying. It never allows you to let down your guard. The sun can be out but the wind will suddenly rev up to 130 miles per hour. You can’t afford to be careless and forget what’s beyond the door.”

Sena’s own fascination with these ideas, specifically the power of a severe environment on human behavior, was piqued years earlier. “I was in Lillehammer, Norway, shooting commercials for the 1994 Winter Olympics. At that time of year there were only about three hours of daylight. It was zero degrees at noon and 40-below at night, too cold to go out, so we stayed cooped up in our rooms. After several weeks, it was depressing. We found ourselves sitting around drinking night after night and it began to affect everyone’s mood. My usually mellow producer started screaming if his coffee wasn’t right and threatening to fire people over typos. Grips were fighting in the snow.

“I came home from that experience wondering what could happen to any group of people trapped in a harsh, claustrophobic place, not for weeks but for months,” the director continues. “What if you threw in some dramatic event? What would these people do? I thought it was a great idea for a movie.”

“You find out a lot about characters when you put them under unusual stress. It forces them to reach deep and reveal their best and worst qualities,” offers screenwriter Jon Hoeber, who worked on bringing “Whiteout” to the screen with his brother and writing partner Erich Hoeber. Adds Erich, “Sometimes people can be so bound up with surviving that they lose their moral compass.”

When the graphic novel was published in four installments by Oni Press in 1998, Sena followed it with avid interest. He tried unsuccessfully to secure film rights to the property, which were already spoken for. Then, he relates, “One day my agent mentioned, ‘Joel Silver has a script called Whiteout; are you interested?’ I said, ‘Are you kidding? I’ve been trying to get ahold of this thing for five years!’ So I called him. I said, ‘Joel, I know this project. I’ve been making this movie in my head for years!’”

Indeed, screenwriters Chad Hayes and Carey W. Hayes suggest that the film’s capacity to shock is rooted in “the way that Dominic captures this unbelievable and unpredictable world that so few people know, and the way in which he leads you to realize that being in a whiteout is very much like being lost in the dark.”

It’s no surprise to Sena that South Pole workers undergo psychological evaluations prior to long-term assignments. “The place can definitely get to you. What it comes down to is that some people can handle it and some can’t. People who aren’t necessarily bad end can up doing pretty bad things and that’s one of the themes this movie explores.”

As Beckinsale observes, “All that confinement can create a real powder keg. Explosive emotions are ready to blow and you don’t always know what’s coming. That’s why I love thrillers. I love trying to figure things out and wanting to see what happens next.”

“’Whiteout’ is every inch a thriller, but it’s character driven. It’s very much Carrie Stetko’s story interwoven with the action, like two mysteries unfolding simultaneously,” says Joel Silver. “She’s smart, she’s tough, and it’s a toughness that’s not just physical but a fundamental part of her personality. She commands respect in a predominantly male domain. But she’s also carrying a burden from her past that could complicate the work she needs to do. I have always appreciated strong female protagonists, and particularly in these kinds of stories.”

Caught between the cold and a cold-blooded killer, the troubled marshal’s history is revealed in fragments through the escalating drama around her until it becomes clear why she sought what Gambino calls “a metaphoric purgatory” in such a lonely place.

Says Sena, “We learn she was originally based in Miami. Something happened there that made her question her instincts and wonder if she’s good enough at her job. So she retreats to the middle of nowhere and as far away from Miami as you can imagine, a place where nothing ever happens and she doesn’t even have to carry a gun. She doesn’t expect to be challenged here and, more importantly, her compromised judgment—if, in fact, it is compromised—won’t put anyone’s life in jeopardy.”

Sena believes Stetko’s decision to dig in and investigate Weiss’s murder is a significant turning point for her. “In that respect, it’s kind of like a classic Western and she’s the marshal in a one-horse town, forced to pick up her gun again.”

“What I found intriguing about the story and about Carrie Stetko is how human and flawed she is,” says Beckinsale. “Because you don’t know her backstory, you don’t know what she is capable of until you see events unfold. How damaged is she? Are her instincts still good and will they carry her through or will they fail her again?”

Stetko’s first lead takes her to Vostok to speak with one of the victim’s former partners. Claiming to be terrified and on the run, he has inexplicably taken refuge at the Russian outpost. There, Stetko encounters U.N. investigator Robert Pryce, played by Gabriel Macht. Pryce has been sent to help expedite the case and control the flow of information about the crime—the first of its kind in a continent with no central government, loosely controlled by a multi-national treaty. In many ways, Pryce could prove to be the right man in the right place. But from Stetko’s point of view, his arrival only means that she now has something else she wasn’t looking for: a partner.

Says Macht, “Pryce offers his help but finds her disinterested to the point of hostility. From that beginning, it’s interesting to see how he attempts to gain her trust. What develops is a kind of cat-and-mouse element between them that mirrors the cat-and-mouse of their tracking the killer.”

Downey explains, “She’s not sure what to make of him. He appears unannounced on site and essentially forces his way into the case. It seems to her that an awful lot of high level attention is being focused upon the death of one unremarkable geologist.” “Pryce has an interesting background, too, some of which is high-level military, but he keeps his history as close to the vest as Stetko does. Gabriel lets the details emerge subtly in a way that seems very natural for that kind of a personality,” says Sena.

Meanwhile, alleviating some of the tension between the two is the young pilot Delfy, pulled from evacuation detail to fly Stetko first to the murder site and then to Vostok, and who will remain with her as needed. Or, as long as he can keep his plane’s engine from freezing up. Columbus Short stars as the optimistic Iraqi War vet on his first civilian assignment, transporting personnel and equipment through the volatile conditions at the Pole.

“This is Delfy’s second desert, with ice in place of sand,” says Short. “He has an interesting view of the world. He sees the beauty in things, even in this desolate frozen wasteland. No matter how strange or difficult the circumstances, Delfy looks for the positive and the challenge and tries to meet it. To him, it’s all an adventure.” “Columbus was outstanding,” the director declares. “He conveyed, through Delfy, a different perspective on what they were facing, not just with his dialogue but his whole approach to every new threat, as if to say, ‘OK, let’s just deal with this.’”

Not one to stand idly by, the keen-eyed pilot becomes increasingly involved in the investigation and more valuable to Stetko than she could have known when she commandeered his plane. But if Stetko places her faith in Delfy, it will be a rare thing. During her service at the Pole she has come to count very few of her colleagues as friends. On that short list is Sam Murphy, the Amundsen-Scott’s dedicated station manager, played by Shawn Doyle, and Dr. John Fury, its only medic, played by Tom Skerritt.

Stetko and Murphy may have been more than friends at one point but, if so, that situation appears to have evolved into an unsentimental but nuanced working relationship by the time the story opens. In truth, it’s Doc with whom she has forged the closest connection. A first-rate card shark, the good doctor is also an excellent conversationalist— partly for the stories he has accumulated in his many years of Antarctic service, but mostly for the fact that he knows when to keep quiet, not ask questions and let things go.

Skerritt offers his perspective, saying, “Doc is a friend. He knows Carrie came to Antarctica to put distance between herself and some complication or betrayal back home, some things that become partially revealed in time. Doc has had his own difficulties. In some ways they’re a lot alike.”

Acknowledging that neither character is particularly open, Downey says, “There’s a great deal of depth that Tom and Kate bring to their scenes together, as kindred spirits who seem to get an awful lot out of a card game or just shooting the breeze over drinks at the end of the day.”

By contrast, most of the men with whom Stetko has been confined there fall into a category best typified by pilot Russell Haden and his rowdy comrades, who spend their off-hours drinking and pulling harmless pranks like frat boys—an understandable tension release after pushing themselves and their planes to the limit. “The pilots in this part of the world are an extraordinary breed. On the one hand, as most would readily admit, they have to be a little crazy to take this gig. On the other hand, they have to be phenomenally skilled and competent to navigate in this treacherous terrain,” says Greg Rucka, who confirms that many of the workers’ onscreen antics, like using million-year-old ice cores to cool their drinks, are authentic and served as comic relief to the story’s darker themes.

Alex O’Loughlin, who stars as Haden, admits, “He’s a pretty audacious personality. He has a lot of energy and confidence, and is a bit of a smartass. He does okay with the ladies, although not with Carrie, and rather than be discouraged by that unfortunate fact, he just tries harder and more shamelessly every chance he gets.”

“Alex was a real find, such a natural, charismatic actor,” says Gambino. “A good portion of his dialogue was ad-libbed.” To which O’Loughlin responds, “The role called for a cheeky Aussie pilot. I thought, ‘I don’t know how to fly but I’m a cheeky Aussie,’ so I figured I could handle it.”

O’Loughlin’s first scene in “Whiteout” introduces Haden and his buddies in a naked sprint patterned after a genuine South Pole tradition known as The 300 Club. Screenwriter Erich Hoeber explains. “It’s called that because it involves soaking in a sauna at 200 degrees, then running outside naked at 100-below for a few seconds, touching the South Pole marker and then racing back inside before you freeze to death.” Doing their own research, the Hoebers unearthed a wealth of such stories about how people in Antarctica cope during extended assignments. Citing Greg Rucka’s initial investment in local lore, Jon adds, “He wove so many interesting details into the story. The more we got into it, the more we discovered additional angles and, since we had a bigger canvas to work on, we were able to build on that and fill in some more of the color. It’s all part of the background of the movie and the action.”

In this relatively tight-knit community, Stetko has lived and worked for two years and has developed a certain level of ease, but that ease evaporates as Weiss’s murder now calls into question every association and casual contact. How well does she really know any of these guys?

“With everyone on the ice wearing multiple layers of protective gear, it’s impossible to differentiate one face from another even if she knew who she was looking for,” Gambino adds. “Most troubling is the timing. With most of the South Pole workers either on route home or preparing to leave before winter prohibits all air transport, Stetko faces the discouraging possibility that the killer might already be gone. Or, he could be right beside her.”

Working and Fighting for Your Life

Seeking a practical location that would evoke the cold, the barren spaces and utter remoteness of the South Pole, the filmmakers relied upon executive producer Don Carmody, a veteran of nearly 40 Canadian-based productions, who says simply, “I know where the snow is.”

Carmody adds, “The first lesson about snow is that it generally doesn’t stay where you want it. It can be hard to find a place that will be iced over for the time you need it. Since this was meant to represent Antarctica, we not only needed snow but an expanse of flat surfaces to recreate those incredible South Pole vistas and a frozen lake that would support a set.” Following an encounter with an inquisitive polar bear while scouting locations in Churchill (“It was as big as a Volkswagen,” he swears), Carmody and production designer Graham “Grace” Walker found what they needed outside of Gimli, Manitoba.

Arriving on set to shoot the exterior scenes of the film was a bracing experience for the cast. Says Tom Skerritt, “It didn’t have to be Antarctica. Manitoba is plenty cold. Everywhere you look, the ice is endless.” At times during the shoot, the mercury at the Northern Canadian locale dropped lower than numbers logged that day at the South Pole.

Having worked in Budapest, Prague and other parts of Canada, Kate Beckinsale believed she had a fair tolerance for cooler climes, but concedes, “This was a whole new level of cold. My first breath outside made me cough like my throat was seizing up. People were walking around with frost on their eyelashes and in their beards.”

To allay anxiety and help protect the cast and crew, production managers provided everyone with what Beckinsale jokingly calls “a telephone directory on all the different ways to die or be injured from the elements: frostbite, hypothermia, exposure. It was terrifying. Columbus and I were convinced we’d never get out of there alive.” “Yeah, the smart people on set didn’t read that,” Macht teases.

Aside from the camaraderie it fostered, one practical advantage to the weather was how it allowed for protective padding under clothing for the high-impact stunt scenes. At the same time, that posed its own challenge. Says producer Downey, “It takes a lot of effort to move around with all those layers. The logistics of just getting from point A to B, let alone staging an action sequence, can be exhausting.”

Beckinsale rises to the challenge physically in “Whiteout,” in which the action unfolds not as superhero fantasy but as a series of gritty life-and-death struggles between people desperate to survive. In that respect, notes Joel Silver, she brings credibility and tenacity to the character. “She makes you believe that she will use her gun and her fists and anything else that is available to her when she has to.”

Says Beckinsale, “The action is based in reality and I think that will make it more intense for audiences because they might imagine what they would do in the same situation. Stetko is not some fearless, invincible being with superpowers, scaling walls and fighting off 14 attackers simultaneously; it’s not that kind of movie. She’s often taken by surprise and reacts on a gut level.”

“Whiteout” placed Macht under the tutelage of stunt coordinator Steve Lucescu for the second time, following their work together on “The Recruit” in 2003. Says the actor, “It was like roughhousing with my brothers, growing up. I had a great time playing around in the snow with the stunt crew. It brought back fond memories.”

During one perilous pursuit, characters best described as hunter and prey confront each other while clinging blindly to rope guidelines, or “storm lines,” to avoid being blown into oblivion by the gale force winds of an Antarctic whiteout. Writers Chad Hayes and Carey W. Hayes orchestrated this sequence, involving multiple colored ropes connecting the various out-buildings of the Amundsen-Scott. “It’s like fishing line, and you have to hook into it to get from here to there. There’s a green line, a yellow line, a blue line… and we have people crossing from one to another, constantly changing course,” Carey explains.

Adding to the risk, Chad cautions, “is not knowing which way to move when one end of the line leads to safety and the other end could deliver you into the waiting arms of a killer. You can’t see. When you feel the rope ahead of you tightening it means someone else has just hooked onto that line. But how far away is he and which direction is he moving in?”

As the characters grapple with one another, some of these lines are severed, propelling them wildly out of control. Lucescu used winches, computer-calibrated to each actor’s measurements, to safely monitor their acceleration and deceleration across the ice. Still, there were moments when Beckinsale fought to remain upright. “She got knocked over several times,” Sena remembers. “Kate has a small frame, so when she got too close to a fan it could blow her off her feet. But she kept getting up; she was a real trouper. We dragged her across the ice. There are many things a stunt double can do but you want audiences to see the actors’ faces and know it’s them as much as possible. I had a fantastic cast. We put them through hell and I couldn’t have asked for more enthusiasm and commitment. I just hope their bruises have healed now and that they’ve forgiven me.”

Building a Set on Ice

An hour’s drive from Gimli and an approximate two hours from Winnipeg, the “Whiteout” set took over a spit of private land jutting into Lake Manitoba that offered multiple shooting angles guaranteed not to catch a tree line or hint of cityscape. Best of all, the shallow lake provided four feet of solid ice. The downside, Don Carmody explains, was that everything had to be brought in, “from gear to steel beams to Porta-Potties. There was no electricity, nothing.” The first arrivals laid roads so the rest of the crew could get in.

Grace Walker, marking his fifth collaboration with Joel Silver on “Whiteout,” notes that the producer is always looking for “something fresh, something that hasn’t been seen before.” This gave him some creative leeway in presenting the American Antarctic base, especially inside.

“In keeping with the almost lunar landscape at the South Pole, the idea was to build a research center that looked a little like you would imagine a space colony to look like,” says Silver.

Thinking “modern but functional and industrial,” Walker used floor tiles on the walls, with exposed piping and stainless steel to get good reflections. “The walls are primarily pinboard, appropriately lightweight and cheap to take to the South Pole. By comparison, Vostok is older and shabbier with a 1960s or ‘70s vibe, which is true to life because Vostok doesn’t have the funds the Americans have for their base. There were no practical locations, every scene in the movie is something we created from scratch,” the designer says, adding that the first floor was a physical set but the upper levels, where no action takes place, were CGI extensions.

“The challenge was timing,” Downey explains. “Gimli gets so frigid at a certain time of year that nails just shatter when they’re hit by a hammer. At the other end of the schedule, beyond a certain period, the lake begins to melt under you.”

“Of course, it was our luck that Manitoba was having the warmest winter on record,” Sena laughs, though emphasizing that “warm” is a relative term. He and cinematographer Chris Soos had to rely on cameras specially oiled to resist freezing, with special heating units attached to each magazine just to keep the film running.

The construction crew—a combined force of set specialists and local carpenters— faced a number of interesting logistical problems: equipment would freeze and stop working, cables would crack, high winds struck down newly raised walls, supply trucks got stuck in the snow and generators seized. In addition, the lake bed was too fragile to support the weight of standard cranes so the visiting team learned from the locals how to rig Bobcats to hoist siding into place.

Trucks delivering bolts or wall panels and larger pieces built in warehouses in Winnipeg often got delayed in transit. “There was always at least one tow truck bringing up the rear when we traveled to the set because invariably one of the convoy would slide off the road and need to be retrieved,” Sena recalls.

Oddly, in a place where cold was taken for granted, one of the biggest issues was spot-thawing, which wreaked havoc on the newly constructed sets. The temperature might be minus-30, but if the sun came out and hit the steel beams they would soak it up. That, plus the weight of the steel itself, would begin to melt the foundation they rested upon just enough to shift the whole structure. Ultimately, the steel was insulated against the sun’s rays, and foundations shored up with gravel.

Striking sets and moving out was another race against the clock with its own perverse humor. Says lead carpenter Tony Parkin, “A day before we got word to pull the set down, the weather changed from minus-15 to plus-2 and it rained. We could have traded our overalls for skin-diving suits for the amount of water that suddenly appeared.

The whole place turned into a marsh and we were constantly sinking. At one point we had three trucks hooked up to each other and a crane to pull the first truck out of the mud.” Volunteers from the nearby communities of Gimli and Eriksdale lent their help, and portions of the set not earmarked for additional filming were left in their hands to be recycled into a planned daycare center. The crew also took care not to leave anything behind that could end up in the lake and be toxic to fish and other wildlife.

Production then moved the outdoors indoors, transporting and recreating the pieces of their set like a giant jigsaw puzzle on soundstages in Montreal.

“We wanted the big whiteout storm scene on stage where we could control it and that meant moving the foundations of four interconnecting buildings—the station and airplane hangar—to Montreal. We then used giant fans to blast them with fake snow, really beat them up with tons of salt,” says Sena.

The special effects crew created a variety of indoor snow: some lightweight for blowing in the background, some in blanket form, some designed for having boots sunk into and some to blow onto the actors. Additionally, 120 tons of sand was mounded up and covered with 12 tons of salt to create giant drifts.

By Gabriel Macht’s estimation, it was the artificial snow that caused more difficulty than anything they had encountered on the Gimli ice, mainly because it tended to adhere to skin. “Some scenes required a lot of physical exertion and that meant heavy breathing, so we needed to keep our passages open. The stuff got into our mouths and ears and up our noses. There was no avoiding it.”

Fellow faux-snow victim Alex O’Loughlin offers his own take on it. “It’s starch and salt, so you felt like you’d been rolling around in pizza dough all day.” Whether manufacturing snow, building sets on a frozen lake or staging a full-scale whiteout, every effort was made to offer entry into a world that few will ever experience.

Says Sena. “Rather than taking a stylized approach, I wanted to bring this story to the screen in a realistic way and present this environment as true to life. Antarctica is such an unforgiving place, and the whiteout is a powerful phenomenon. When those things hit you can’t see three feet in front of you and your life expectancy can drop to minutes. It really makes a compelling setting for a mystery.”

“The idea was to transport audiences to Antarctica. We want them to feel the cold, the fear, the isolation and the will to survive in this extraordinarily difficult and alien environment,” says Silver, before advising with a smile: “Better bring a sweater.”

Production notes provided by Warner Bros. Pictures

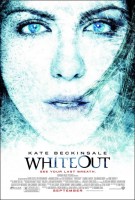

Whiteout

Starring: Kate Beckinsale, Gabriel Macht, Tom Skerritt, Columbus Short, Alex O’Loughlin

Directed by: Dominic Sena

Screenplay by: Erich Hoeber

Release Date: September 11, 2009

MPAA Rating: R for violence, grisly images, brief strong language and some nudity.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $10,159,013 (93.2%)

Foreign: $746,921 (6.8%)

Total: $10,905,934 (Worldwide)