About the Production

Remember Woodstock? Well, if you do, as the saying goes, then – you probably weren’t there.

While Woodstock itself is a great subject, it’s one not readily able to be captured in a film – and, furthermore, it’s been done definitively; Michael Wadleigh’s threehour 1970 documentary feature Woodstock won an Academy Award. Taking Woodstock producer James Schamus, who adapted the film’s script from Taking Woodstock: A True Story of a Riot, A Concert, and A Life, written by Elliot Tiber with Tom Monte, explains, “What we’re doing is telling a tiny piece of that story, from a little corner of unexpected joy that happened almost by accident and which helped this incredible event take place.”

It was almost by accident that Tiber’s tale happened to come to Schamus’ longtime filmmaking partner, Academy Award-winning director/producer Ang Lee. In October 2007, Lee was booked on a San Francisco talk show to discuss their film Lust, Caution, which was about to open locally. Tiber was booked on the same show to discuss his book, which had been published. While waiting to go on, Tiber struck up a conversation with Lee, and gave Lee a copy of his memoirs. Lee remembers, “A few days later, an old friend from film school, Pat Cupo, called. He told me he had heard that Elliot had given me the book, and encouraged me to read it.”

Tiber enthuses, “Getting the `yes’ from Ang Lee was truly the ultimate trip. I have found in my life that whether you find the action, or the action finds you, the crucial thing is to act – and always now.”

Lee saw Taking Woodstock as following naturally from his previous work. If his 1973-set movie The Ice Storm was, as he says, “the hangover of 1969, then Taking Woodstock is the beautiful night before and the last moments of innocence. “After making several tragic movies in a row, I was looking to do a comedy – and one without cynicism. It’s also a story of liberation, honesty, and tolerance – and of a `naïve spirit’ that we cannot and must not lose.”

Schamus also cottoned to the project immediately, and saw bringing the film to audiences as an opportunity for “a new generation to go back and visit Woodstock and get a feel for what it must’ve been like when you could have hope, and really move some mountains and enjoy it.

“Because we embraced that ethos, Ang actually enjoyed the hard work on this film. This is Ang’s and my eleventh film together; he keeps raising the stakes for himself and meeting new challenges.”

To make Taking Woodstock, the pair was joined by two-time Emmy Award-winning producer Celia Costas. She notes, “Ang Lee was going to be making a movie about when I came of age, almost in my backyard – an opportunity I couldn’t pass up! “In the late 1960s, the world was your oyster, whether politically or socially. We were in the middle of a war, but despite that it was such a positive time and we felt that if we got together we could do anything. That’s something which has sorely been missed, and perhaps we are trying to begin to recapture that now.”

Costas found that “with his script, James created a smart and funny world that Ang can flourish in; he’s able to give Ang situations and concepts that Ang, as a unique humanist filmmaker, can – and does – run with.”

Schamus notes, “Underneath all the comedy in this movie are emotions, and meditations on what it means for people to transform themselves.”

In those respects, this latest work harkens back to the Lee/Schamus team’s earliest collaborations, while also continuing Lee’s career-long exploration of familial/generational dynamics. For Elliot and his Jewish immigrant parents Sonia and Jake Teichberg (portrayed in the film by acclaimed U.K. actors Imelda Staunton and Henry Goodman), getting unexpectedly caught up in the preparations for Woodstock gifts them all with a learning experience, and then some; “For the first time in their lives, they have the opportunity to emotionally reveal themselves to one another,” notes Costas.

Schamus adds, “In the midst of a great cultural moment, Elliot comes to fully accept who he is. His gay identity is part of the story, and so is his identity as his own man – not just as his parents’ son. Woodstock is freeing and transforming for all three of them, but it’s Elliot’s life that’s the most positively impacted.”

Demetri Martin, of the hit cable series Important Things with Demetri Martin, makes his feature starring debut as Elliot Tiber in Taking Woodstock. His and Jonathan Groff’s casting are just the latest examples of Lee’s eliciting breakout performances from fresh talent in his movies; Martin had been brought to the attention of the filmmakers by Schamus’ teenaged daughter, who had urged her father to watch a clip of one of Martin’s comedy routines (“The Jokes with Guitar”) on YouTube.

Viewing additional routines and footage, Schamus had liked what he saw, which was a presence conveying “a ferocity of intelligence, coupled with a non-assaultive style and vulnerability that is unusual in a stand-up comic.”

Just as the story had suddenly found Lee, Martin’s audition and screen tests convinced the director and Schamus that they had found their leading man. “I’d never worked with a comedian,” muses Lee. “But we made a very good choice. You want to see more of Demetri; you like him, he’s a fresh face.

“In his demeanor and his disposition, he is very close to the characterization in the script. Plus, he’s genuinely funny.”

Martin says, “In stand-up I’m trying to be myself. Doing this meant I would have to be someone else, and interpret another writer’s words and storyline.”

The actor was immediately intrigued by the emotional arc of his role. He notes, “When we first meet Elliot, he doesn’t have a real relationship with anybody. He seems kind of stuck between obligation to his family and cutting the cord. Guilt seems to be a big part of what keeps him in the kind of behavioral patterns he’s in. “For me, this was an exciting opportunity to work with Ang Lee and learn about acting.” Martin did just that, logging three weeks of rehearsal prior to the start of filming and also spending time with Tiber “to ask him about some specific details.” Costas assesses Martin as having “great timing and great instincts. He’s perfect for Elliot, like Dustin Hoffman was perfect for The Graduate.”

By the spring of 2008, the project was quickly coalescing. As always, Lee went to great lengths to marshal research. David Silver, hired as the film’s historian, was given a mandate to put together what became known as the “Hippie Handbook,” a compendium of articles, timelines, essays, and a glossary of “Hippie Lingo,” from “freak out” to “roach clip.” (Selections from the glossary can be found on page 18 of this document.)

Even words that had long permeated the culture were re-investigated. Silver reveals, “The first hippies were 19th-century German immigrants who came to Northern California and lived a communal agrarian lifestyle. Some decades later, the term `hippie’ derived from `hipster’ and `hip,’ the idea being that these people as a whole were cool.

“The word has a light feeling, and did not necessarily mean someone was radical, or an activist. They were more interested in smaller, interactive changes between and among people.”

Lee clarifies another point, noting that “Woodstock didn’t happen in Woodstock. But we don’t think of it as `White Lake’ or `Bethel,’ we say `Woodstock.’”

Location filming was set for New York State’s Columbia and Rensselaer Counties, as well as a couple of days in New York City. Taking Woodstock was one of the first films to take advantage of the enhanced (by 300%) incentives and tax credits that the state now offers; the production boosted the local economy with millions of dollars. So it was that Taking Woodstock moved rapidly towards production – on a parallel summertime track to the three-day Woodstock Music and Arts Festival of peace and music’s own trajectory 39 years prior.

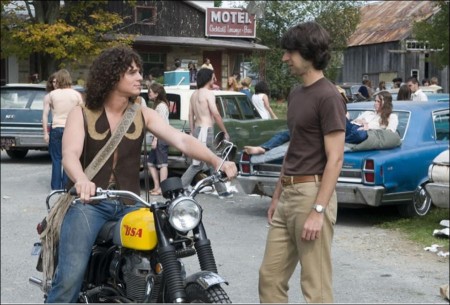

In 1969, the dream-into-action was being realized by Woodstock Ventures’ Michael Lang (played in Taking Woodstock by Groff), Artie Kornfeld (played by Adam Pally), Joel Rosenman (Daniel Eric Gold), and John Roberts (Skylar Astin). Lang had emerged as a memorable figure in the documentary Woodstock, and no less so in Tiber’s account of his own encounters with him. From one producer to another, Schamus praises Lang – who visited the set, met with the filmmakers, and spent time with Groff – as someone “who sometimes put being a businessman first, as he had to – yet he never seemed cynical. It must have been incredibly exhausting; he had to maintain this aura of a beautiful hippie. “Jonathan – whose first movie this is – precisely caught the wave of all of those nuances in Michael’s character.”

Lee worked with Groff to get a performance from the actor capturing, as Groff puts it, “the vibe of Michael – which I had experienced firsthand – while also freeing it up and finding my own version,” while Groff continued to watch the documentary’s scenes showing Lang over and over again each day on the set before filming began.

Beyond sporting the fringed leather vest and long brown curls, the actor aimed for capturing the way Lang stood for “the magical quality of Woodstock while also dealing with the nuts and bolts of putting together a concert and hiring a staff and getting everything done,” representing Woodstock in more ways than one.

“They really launched it on a wing and a prayer,” marvels Costas. “That weekend, there was rain and heat and confusion and traffic and hunger – every element you can possibly think of, except maybe a plague of locusts. But a legacy was beautifully defined in a single weekend.

“So, while the organization of the festival is integral to the comedy at our film’s heart, the festival is still very much a backdrop to our central story of Elliot and his family and friends’ epiphanies.”

The uphill quest undertaken by Lang and his team of festival organizers complements the underdog story of Elliot and his transformation over the course of the summer of 1969. Yet, as executive producer Michael Hausman notes, “literally and figuratively, the festival remains just over the hill from the motel and the people there.

”

As Schamus points out, “If anyone is coming into the movie waiting to see who plays and lip-synchs Janis Joplin at the festival, well, that’s not in Taking Woodstock and was never going to be.”

Instead, a transformative human story is placed in the context of a transformative cultural event. As comedy icon Eugene Levy reflects, “The timing was right for Woodstock; it was at the end of probably the most dynamic decade of the 20th century. I have to admit I didn’t know a lot about Woodstock before it happened, but on the weekend it was underway, it started hitting the news in a major way.”

Martin marvels, “I’ve been a fan of Eugene’s since I was a kid. The role of Max is one different than people are used to seeing him do, and in my scenes with him I felt like I was lucky to have a front-row seat.”

“Ang wanted me to look and sound like Max as much as I could,” reveals Levy. “I read up on Max and looked at what little footage exists. Ang described Max to me as an old-school Republican – the Abe Lincoln kind, who respected the freedoms that the party stood for initially.

“Woodstock was a business venture for him, and Max grew to love what it turned into. He had suffered a serious health crisis about a year before, and after that he decided that nothing seemed quite so scary or intimidating. He stood among the townspeople and said, `There’s nothing wrong with these kids.’”

In counterpoint, Jeffrey Dean Morgan is cast as Dan, whom the actor describes as “a community leader, seemingly happily married but not. The town he’s part of is set in its ways, and the residents are none too happy that thousands of hippies are coming to town.

“But the world, and their world, is about to change. Who would have thought that a concert could do that…”

…even a concert whose attendance organically grew and grew and grew, benefitting the town and its people. Levy acknowledges, “Yes, Max bumped his price up when he heard how many people were coming, but he told the promoters that he would back them up – and he did. So, he was a man of his word and a good businessman.” The “good businessman” description could not be applied to the Teichbergs, but, as Levy notes, “Elliot and his parents made a lot of money in a short time. It’s a turning point for them.”

Goodman, as the Teichberg patriarch, sees the family’s benefits as more than financial. He emphasizes, “Each person, in their different way, moves forward in positive steps through the course of the movie.”

Martin remarks, “At first, the family’s lives are joyless; Jake and Sonia feel kind of stuck with each other.”

While Goodman had known Staunton from having starred together onstage years prior, he was gratified at how “Ang worked to start a dialogue among our on-screen family. He was keen for Imelda and Demetri and I to come together for over a week. That way, by the time of filming, we could connect to each other and get to places very quickly as actors.”

Costas lauds the actor’s ability to convey “how Jake, who is so unhappy, comes alive and opens up like a flower. Henry is wonderful in the role.”

Schamus states, “By the end of the movie, he and his son have made a real connection – and it’s not at the expense of Mom.”

With her nature forged by her immigrant history, Elliot’s perpetually disapproving mother Sonia is the source of comedic moments in the film. But, as Staunton notes, “Those come from a very dark place – which, of course, most of the best comedy comes from. Ang and I discussed how I would not be playing it for laughs. What Sonia grew up with in Russia has never left her.

“Therapy-speak doesn’t exist in her and Jake’s lives. They haven’t got a large emotional vocabulary. There’s nothing better for an actor than to get hold of a good character; I do what’s right for the part.”

Staunton’s modesty belies her commitment to fleshing out the character; as costume designer Joseph G. Aulisi remembers, “I spoke to Imelda on the phone from London. She said, `You’ve got to give me some help because I move much too quickly,’ and we all saw Sonia as a more rotund woman. So I designed a body pad, which we filled with birdseed and adapted to some actual early 1960s housedresses so that it would move with her body. It worked well enough that most people didn’t recognize her without her body pad and her wig.

“Now, most actresses will not wear something sleeveless, but Imelda wanted the housedresses that way. She gets so into the part that everything she does is made believable, with her wonderful physicality.”

In contrast to the petite Staunton stands 6’3” actor Liev Schreiber as Vilma, the cross-dressing ex-Marine who joins the Woodstock preparations by becoming security detail at the El Monaco hotel. Vilma’s mere presence helps cue an essential realization for Elliot that he must live his life as a gay man “and he ever so gently encourages Jake and Sonia to live their lives, too,” notes Costas.

Lee sees Schreiber’s character as “someone who has found peace within himself, though not without struggle, and is therefore a role model for Elliot.

“We are all very complicated creatures. How can all these elements – wartime experience, cross-dressing, goodness – coexist in one person? But they do, and it’s not Vilma’s problem; if it’s anyone’s, it’s yours. This was a true acting test for Liev.” Schamus adds, “As played by Liev, Vilma is a force of nature. Like all of the other characters, she has her own transformations that happen.”

Schreiber, in his research, “found that the whole gender-bending movement was very active by 1969. Vilma embodies contradictions, not only of sexuality but also in her own character. Those contradictions were the most interesting part of the role for me. She hasn’t stopped being masculine, and hasn’t stopped being feminine; she just is, she doesn’t worry about judgment, and she is generous and protective. “Since I’d done it before, I had no real concerns over playing a man in a dress. Well, there is always the concern that you might not look good in a dress.”

Aulisi remarks, “We capitalized on Liev’s height and biceps, and made it work for us. Headbands helped give Vilma a female aura. Ang and I had initially sparked to a scrapbook I found which showed men who went to the Catskills in the late 1950s and dressed up as women. Then, with Liev’s input, we updated Vilma’s wardrobe to the late 1960s and made it more casual and comfortable – reflecting the freedom that was starting to happen.”

More freely expressive from the get-go are the local avant-garde theater troupe the Earthlight Players. Aulisi laughs, “I got a lot of horrible yellows together for them, and since they have no money we did very easy costumes that could have been made by them – and could come off easily!”

Dan Fogler, cast as Earthlight Players leader Devon, calls the group “very serious actors who do very silly things with their bodies.” To make sure that the actor would be a credible troupe head, Lee encouraged Fogler to work closely with choreographer Joann Jensen on coordinating the group’s surprising turns. Fogler remarks, “I was told how particular Ang is, and he’s an incredible captain of the ship, but he also brought a sense of trust and a sense of play – he would get up there and do the troupe’s moves to show us what he wanted!”

Production designer David Gropman notes, “The wonderful thing about Ang is how he undertook to completely understand the world and the culture and the time that the story took place in.”

Lee remarks, “Working on Taking Woodstock, I began to feel a passion for the `60s.”

But even this pales in comparison to the director/producer’s passion for detail. Weeks before filming began, Lee gave Groff – who was then in the midst of performing in a revival of Hair – a binder of assembled research as well as 10 mix CDs of important music from the late 1960s and DVDs of some 20 movies from and about the period.

Emile Hirsch, cast as Vietnam vet Billy, offers, “That attention to detail is what makes Ang’s films so rich. Ang sent me probably 30 DVDs; Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter, Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, Hamburger Hill, the documentary Winter Soldier…not just Vietnam-themed films but World War II movies as well – and Fantastic Voyage, which was amazing!

“Another key assignment that Ang had me do was to go to a shooting range to get some experience. I also met with an Iraq War veteran who took me through his own experience and discussed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with me, since that is something that Billy has.”

Veteran costume designer Aulisi marvels, “I have never worked with a director who has done so much homework, and who has such an incredible vision of what he wants to achieve. He remembers every photograph you have ever shown him. He knew the material so well and cared about it so much that it was impossible for us not to care as much and share his vision.

“Overall, we used as many genuine clothes from the period as we could get, gathering an enormous amount of clothing from over 50 different sources. But on days calling for many extras [a.k.a. background artists], clothes had to be physically executed in a couple of hours. 1969 marked a major turning point in fashion – although the townspeople are slightly behind the times, so their look is more early 1960s/Montgomery Ward catalogue.”

Lee and his team assembled a “war room,” where a massive flow chart/spreadsheet was posted on a 30-foot wall. Post-Its in every imaginable hue chronologically marked both the shooting days and the days of the action in the film, and emotional and physical progress of characters as well as the usual issues of continuity; e.g., what color the water in the motel pool should be from scene to scene. Also marked were what Lee and historian Silver called “vignettes;” little scraps of information and kernels of interest gleaned from Tiber’s book, the documentary feature and other filmed and photographic records, and all the assembled research.

Costas reports, “We were steeped in what people were listening to and reading; what art they were looking at; and what programs and commercials they were watching on television. It was multimedia exposure. Certainly, there was a lot about the festival that we weren’t aware of.”

One cluster of information posted, for instance, centered around food: how, during the festival, it nearly ran out (the few commercial concessions sold out early, and the town’s coffers were nearly depleted) until everyone benefited from the efforts of the Hog Farm, the hippie group from California (founded about two years earlier by Hugh Romney, a.k.a. Wavy Gravy) who cooked and dished out food for free. Another “vignette” was a scene inspired by the documentary, of a man painting a daisy on a woman’s face; Lee wanted it – and many more – re-created in the film, as part of cinematographer Eric Gautier’s capturing the essence of the period and the Woodstock ethos.

Lee reminds that “in all this source material, there can be differing versions of what happened. Eventually, you have to decide at what times to take creative license.”

Indeed, what came up in the “war room” ran contrary to 40 years’ worth of shared perceptions. Schamus reveals, “The people who went to Woodstock were not all hippies with long hair and sideburns smoking joints. Although those are the pictures that ended up being reproduced the most, a lot of the attendees didn’t look that different than young people do today. Our decision was, let’s access the `expected’ look, but also give the reality.”

To further quantify; the team’s research had determined that hippies – who tended to be nomadic in nature, traveling from event to event – had arrived at the festival site first, followed by college kids – some, but by no means all, with longish hair – and then by the other 85% of the attendees, high school students and other assorted “straights” – people who had shorter hair and generally wore nondescript clothing.

Accordingly, the flow chart on the wall was amended by Lee to divide up the background artists into seven “tribes;” among them the Willow Tribe, the Biker Tribe, and the Pool Tribe. Script supervisor Mary Cybulski reports, “This was so that when we actually got on the set and there were hundreds of extras, culled from our open casting calls across five states, we knew who should be doing what and when – and where they fit in.”

Lee points out, “This was also so I could see them better – there were hundreds of people!”

Extras casting director Sophia Costas reveals, “We were so fortunate to find a lot of people who live communally today, and who are committed to living by the tenets that the young people at Woodstock were trying to espouse. Some of these people `looked right’ because they really lived – and live – that life, and were able to present themselves purely and innocently, which shows up on camera.

“Ang took an interest in the extras casting, and wanted to make sure we showed how this event was a meeting place for all different types of philosophies and people, who co-existed peacefully for three days. So you will see everyone from Hare Krishnas to Hasidic Jews on-screen.”

Schamus points out that “there was not one single reported incident of violence at Woodstock. There was just celebration.”

Cybulski adds, “Ang wanted to make sure that we really felt the rush, the flood of all these people and new ideas coming through a small town. So he wanted the background artists to be very specific. Lots of times in movies they’re just people hanging out, but he wanted something more potent.”

Second second assistant director Tudor Jones elaborates, “Ang’s scrutiny is allen-compassing. Even if someone is 300 yards from the lens, he will want that person to be in the right posture with the right attitude and the right look – and he’s very sensitive to someone who’s not at the right emotional level in the scene, so he’ll keep doing it until he finds it to be right.

“You feel like your job is worth it, unlike with directors who don’t notice the hard work you’re putting in.”

Lee also sought the ideal barn for the scenes with the Earthlight Players. The search yielded one – in New Hampshire. So Lee had the structure disassembled piece by piece and trucked to the location shoot – where it was then put back together. Once shooting wrapped, the barn was returned.

An even bigger logistical challenge facing the production was staging the so-called S-road scene, in which a state trooper carries Elliot on the back of his motorcycle from the motel towards the concert site. The motorcycle weaves through an enormous line of stalled traffic – and festivalgoers on foot – backed up along a serpentine road almost as far as the eye can see. Calling for hundreds of extras and over 100 vehicles, the scene was successfully filmed in just one day.

“With our great crew, we got it – and without one complaint, from either background artists or townspeople! It was the most challenging scene,” asserts Hausman. “Here, too, we had iconic images we wanted to reproduce. With a recreation of this magnitude, we did rehearse it the day before.”

The majority of the 42-day shoot ended up taking place in the town of New Lebanon, in Columbia County – marking the first time that a major motion picture had been filmed there.

Residents’ vintage cars – from “Love Bug” Volkswagens to panel vans – were back in their element for scenes, some for their last mile; picture car coordinator Philip Schneider reports, “Several of these were just hanging on, and during the S-road scene, a number fell by the wayside.”

A retired but still intact motel, the Valley Rest, was put back into temporary operation and re-dressed and restructured by Gropman and his crew to play the (no longer existing) El Monaco. “True to the actual motel and all of those Catskills motels of that era, everything was painted white,” points out Gropman. “We did put little splashes of color on some of the trim and doorways – working from photographic records and re-creating what Elliot had done.”

Schamus praises Gropman “and his whole team for studying Elliot’s family history, and the history of the Catskills and what it meant to be a Jewish family out there. When you walked onto that location, you were seeing these lives as they were lived.” The Hitchinpost Café met one of the production’s most specific requests by delivering 500 eaten corn cobs for a scene, after making sure that local schoolchildren were given the corn first as a free lunch.

“Without the enhanced tax credit incentive, we never could have filmed in New York State,” asserts Celia Costas. “Rarely have any of us had a better location filming experience. The people from the town of New Lebanon, and throughout Columbia and Rensselaer Counties, were warm and welcoming and became terrific partners in the experience of making the film.”

Throughout the production, environmental steward Nicole Feder oversaw implementation of an extensive on-set recycling program. For the scenes requiring hundreds of extras, water stations and/or stainless steel water canteens staved off use of plastic water bottles and accompanying waste. It was all, as Celia Costas notes, “in keeping with the spirit of the movie.”

Comparing environmental efforts across the decades, Schamus point out that “while there were 600 acres of trash left behind at Woodstock, 400 volunteers did stay and clean it up. So even that was beautiful!

“Woodstock was three days of peace and music, and this was three months of peace and movie.”

Lee concludes, “With our great cast and crew, we felt the energy and the spirit of the Woodstock experience. We had a blast!”

Taking Time: The Road to Woodstock

1935 Eliyahu Teichberg (whose name is later changed to Elliot Tiber) is born in Brooklyn, New York to Jewish immigrant parents

1955 Jacob (Jake) and Sonia Teichberg, the parents of Elliot Tiber, buy the El Monaco Motel in White Lake, New York and operate it with their son December 1960 The birth of “The Pill,” a birth-control method that effectively revolutionizes sex

1963 Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique is published, marking the beginning of modern feminism

August 28, 1963 During the Civil Rights March on Washington, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivers his “I have a dream” speech

Nov. 22, 1963 President John F. Kennedy is assassinated; Lyndon B. Johnson is sworn in as President

February 9 and 16, 1964 The Beatles appear on The Ed Sullivan Show

July 2, 1964 The Civil Rights Act is passed

August 2, 1964 The Gulf of Tonkin incident in southeast Asia, where the Viet Cong are waging war in South Vietnam and the U.S. has been building up troops, spurs the Senate to pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution urging LBJ to wage war against Vietnam without a Declaration of War

February 21, 1965 Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X is assassinated

March 21, 1965 First anti-Vietnam War Teach-In is held

January 14, 1967 “Human Be-In” is held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, drawing @30,000; Timothy Leary coins directive “Turn on, tune in, drop out”

June 16-18, 1967 The Monterey International Pop Festival, held at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in California, showcases many performers who would also play at Woodstock two years later; @200,000 people attend; the documentary feature Monterey Pop is released the following year

Summer 1967 The Summer of Love unfolds in San Francisco, becoming a flashpoint for the full flowering of the hippie movement as thousands of high-school and college-age students head to the city

March 16, 1968 My Lai massacre in Vietnam

April 4, 1968 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is assassinated

June 6, 1968 Robert F. Kennedy is assassinated

January 20, 1969 The inauguration of Richard M. Nixon as President

February 20, 1969 President Nixon approves the bombing of Cambodia

March 11, 1969 Levi’s begins to sell bell-bottomed blue jeans

March 19, 1969 The Chicago 7 are indicted in the aftermath of the previous summer’s violent Chicago Democratic Convention protests

May 15, 1969 University of California officials fence People’s Park in Berkeley despite protests of 3000 people to save it; Governor Ronald Reagan places Berkeley under martial law; one protester is shot and killed

May 23, 1969 The Who release their rock-opera album Tommy

June 22, 1969 Judy Garland dies

June 27-28, 1969 The Stonewall Riots (so named for the Stonewall Inn bar, which was targeted for police harassment) erupt in New York City, marking the beginning of the Gay Liberation movement; Elliot Tiber is among the active participants in the Riots

July 14, 1969 Michael Lang and his fellow producers Joel Rosenman and John Roberts are denied a permit for a music and arts festival in Wallkill, New York

July 15, 1969 Hearing that the festival’s permit has been denied, Elliot Tiber contacts Michael Lang

July 18, 1969 In an accident, Senator Ted Kennedy’s car plunges off the Chappaquiddick Bridge, and his passenger Mary Jo Kopechne dies

July 18, 1969 Festivalgoers begin to arrive and camp out at the festival site

July 20, 1969 The U.S. lands the first man on the moon

August 9, 1969 Members of Charles Manson’s “Family” slay pregnant actress Sharon Tate and four others in California

August 15-18, 1969 “Woodstock Music & Art Fair presents An Aquarian Exposition in White Lake, N.Y.; 3 Days of Peace & Music;” approximately half a million people attend, and more try and fail to get to the site; performers include Joan Baez, Joe Cocker, Country Joe and the Fish, Richie Havens, Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, The Who, and two dozen more acts

September 26, 1969 The Beatles’ final album, Abbey Road, is released

November 15, 1969 250,000 people peacefully demonstrate against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C.

December 6, 1969 The Rolling Stones concert at Altamont Speedway in California, where Hell’s Angels were hired as security, sees violent fighting break out and four people die; footage from the concert is seen the following year in the documentary feature Gimme Shelter

March 1970 Michael Wadleigh’s three-hour documentary Woodstock is released, as is the film’s soundtrack

April 10, 1971 Woodstock does not win the Academy Awards for Best Film Editing and Best Sound, but the picture does win the Academy Award for Best

Documentary Feature: Talking Woodstock

Back in 1969, the following words held meanings beyond their dictionary ones…;

Axe: Any musical instrument, or any tool you use to do your art

Ball: (as a noun) A good time; (as a verb) Sexual intercourse

Bread: Money (“I’m broke – man, can you lay some bread on me?”)

Freak: Insiders’ synonym for hippie (possibly coined by Frank Zappa)

Fuzz: The police

Gas: Sublime (“They’ve never sounded better – that was a gas!”)

Head: Insiders’ term for a member of the counterculture (possibly coined by Ken Kesey)

Lid: An ounce of marijuana

Mike: Microgram

Pig: Hippies’ term for the police

Rap: To speak / communicate in the language of hip

Ripped: Under the influence of an illegal substance

Roach: A small butt of marijuana

Production notes provided by Focus Features.

Taking Woodstock

Starring: Demtri Martin, Emile Hirsch, Liev Schreiber, Imelda Staunton, Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Henry Goodman, Eugene Levy

Directed by: Ang Lee

Screenplay by: James Schamus

Release Date: August 26, 2009

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for crude and sexual content throughout, brief strong language, comic violence.

Studio: Focus Features

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $7,408,607 (92.8%)

Foreign: $577,027 (7.2%)

Total: $7,985,634 (Worldwide)