The author fleshed out his idea further by imagining various reasons people would have for using a surrogate. “My idea was to create this persona that would go to work and earn money for you, a practical reason for having a surrogate. I looked at the idea of self-improvement, where these surrogates represent plastic surgery to the extreme where you could maintain yourself as forever young, or be more muscular—look like your dream self.”

“The story has always spoken to me about technology versus humanity,” producer Hoberman says. “I am someone who has come very late to computers, the Internet, email and iPhones. Until recently, I knew nothing. This story addressed, in a compelling manner, what would happen if everybody basically lived inside a computer, and their lives were being lived by someone else out there. It just spoke to where technology is going. I think it also spoke to plastic surgery and things people do to their bodies. I thought it was an interesting idea to explore in a film.”

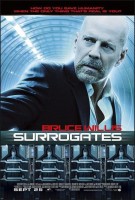

Bruce Willis (“Die Hard,” “Twelve Monkeys,” “The Sixth Sense”) and Radha Mitchell (“Man on Fire,” “Melinda and Melinda,” “Pitch Black”) star as FBI agents Thomas Greer and Jennifer Peters, newly teamed partners charged with investigating a murder. It’s the first murder in years for their utopian society, and one that triggers questions about the ethics of surrogate technology and the future of society.

Says Mostow: “This movie is a mystery, a detective story, with Bruce Willis as an FBI agent whose investigation into the mysterious murder of a surrogate finds the hero confronting a conspiracy that calls into question the very definition of humanity.”

In the film, Dr. Lionel Canter is a reclusive billionaire and M.I.T. genius whose groundbreaking experiments have led to the creation of the surrogate population. Confined to a wheelchair, Canter began experimenting with prosthetic limbs while at M.I.T. His research led to a new technology for decoding brain impulses, which he discovered could be transferred as signals to synthetic humans. These remotely operated “surrogates” are distinguishable from their flesh-and-blood counterparts primarily by their physical perfection. Each surrogate is linked directly to a human being, blocks or hundreds of miles away, who control their replicants neurally. Without a human mind sending and receiving impulses while sitting in a special device called a “stim chair,” these robotic doubles are completely inert.

So, the world of surrogacy was born—to the applause of millions—and the regret and contempt of others. Ving Rhames (“Pulp Fiction,” “Mission: Impossible,” “Con Air”) portrays The Prophet, the selfstyled leader of a group of disaffected citizens who passionately oppose the inhumanity of this technological lifestyle.

“The core idea of ‘Surrogates’ is how we retain our humanity in this increasingly, relentlessly technological world that we live in,” says Mostow. “Technology is great. The fantasy of technology is that it frees us to be creative, productive and to do all these wonderful things. The flip side to that is that we wind up being servants to it in a certain way. We’re tethered to our cell phones, to our BlackBerries. It’s great to have email, but when you spend hours a day returning emails, it becomes an obligation. So, these new opportunities and possibilities in life also restrain us in certain ways.”

“Technology becomes a lifestyle,” says producer Todd Lieberman. “That seems to happen with a lot of technology. It pervades society and people then depend on it in their lives. What would we do today without the Internet? Without cell phones? It’s hard to imagine. In this world, what would they do without surrogates?”

“The story’s just meant to raise such questions,” Venditti concludes. “I don’t know the answers to the questions. When I wrote the story, I wanted people to see the good uses surrogates would present to society, as well as the bad ones. Ultimately, I wanted the readers to make determination themselves.”

Sending “Surrogates” to the Big Screen

Producer Max Handelman, a lifelong comic book aficionado, optioned the graphic novel from Venditti. He found the story’s themes compelling. “The story really moves along at a great pace and allows you to imagine something that could impact our society someday. Are we all going to have surrogates? Probably not. But it’s a metaphor for our society’s increasing reliance on technology and increasingly virtual communication.”

Handelman brought the comic to a college friend, veteran producer Todd Lieberman, who is partnered with longtime industry producer and studio executive David Hoberman at Mandeville Films.

“I was looking for something with an edge, a film noir-type story and I found that in Robert’s story,” says Lieberman. “The movie starts with two really attractive people outside of a club. All of the sudden, some guy approaches and they fall dead. You have no idea what’s going on. In comes a detective, Bruce Willis’ character, and his partner. And you realize pretty quickly that we’re living in a world that’s not our world.

“The two people who’ve been killed are actually surrogates,” continues Lieberman. “Not only are the surrogates getting destroyed, but the people controlling them at home have been murdered, which is something that’s never happened in the history of surrogacy. The entire world of surrogates is at risk because the fail-safe of not harming the user is the cornerstone of the technology.”

Jonathan Mostow agreed to direct the film; his longtime writing partners, John Brancato and Michael Ferris (“Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines,” the 1991 telefilm, “Flight of Black Angel”), were tapped to tackle the script, marking a professional reunion for the trio of Harvard University alums.

“As soon as Mike and I read the graphic novel, we felt it could make a great film,” says Brancato. “The concept of surrogacy speaks to the modern condition in ways direct and oblique, a metaphor at once for the Internet, plastic surgery, addiction, role-playing games. Not to mention outer versus inner selves.”

To capture the flavor the writers sought to depict in this present-day/near-future universe populated almost exclusively by robots, the pair began to research the technology that reflected Venditti’s ideas in the graphic novel. Their studies led the scripters to a Japanese scientist named Hiroshi Ishiguro, who has been using a plastic version of himself to lecture around the world without leaving his Osaka office. They also uncovered a rhesus monkey in North Carolina that has been wired to make a robot in Kyoto walk, merely by thinking. The technology continues to improve with groundbreaking advances that are already benefiting people with debilitating diseases.

Casting the Film

“SURROGATES’” roster of characters includes idealized robots as well as real-life humans. Most cast members were asked to play both.

To bring “SURROGATES’” conflicted FBI agent to life, the filmmakers turned to global superstar Bruce Willis. “He’s really one of the great film actors of his generation,” says Mostow. “It’s a very specific skill to be able to pull off movies that have a very high-concept idea behind them. Here, it’s an alternative reality, and yet he makes it credible. That’s really his gift.”

“The thing about Bruce is he plays a great cop, but he also plays a great Everyman,” says producer Hoberman. “Both from a philosophical and theoretical perspective, that’s what this character is. As he goes through this journey, he discovers what humanity versus surrogacy is, which leads his character to a great crisis. The movie also has action and all the things you’d want to see in a Bruce Willis movie.”

“In the movie, the humanity comes through in Bruce’s character,” Mostow says. “Like everyone else, he goes about his daily grind using this technology. He’s an FBI agent who stays at home, in the safety of his apartment, and allows his robotic surrogate to go out and perform all the dangerous tasks that are involved with his work. At a certain point, he loses his surrogate and is forced to go out as himself and experience life as a human being again in a world that is completely technological and robotic.

“At the same time, he discovers feelings that have been building up inside of him about his own disconnection from his wife, who’s addicted to using her surrogate,” the director continues. “He’s a man who’s in an existential crisis. As he begins to live as a human being, he realizes how warped the world is. He begins to see the world totally differently.”

“I see Greer as someone who has lived in and embraced the surrogate world for some time,” adds producer David Hoberman. “Once his surrogate is destroyed and he can’t get another one, he’s a man, a human, out there in the world. Eventually he has to make a choice.”

Filmmakers called on Australian actress Radha Mitchell for Greer’s FBI partner Jennifer Peters. “Peters is an interesting character because she is actually three different people in the movie,” says producer Lieberman. “She’s the Peters surrogate who is a slightly newer, naïve cop, partnered up with Greer. There’s the real Peters character, a frumpier version of the surrogate, a painter, more of an artistic person. And, there’s a third Peters that’s part of the mystery. It’s a challenge for Radha because of the subtle changes that happen among these three versions.”

“Radha’s casting was an interesting process,” Hoberman says. “She has a great pedigree. We’ve seen her in ‘Finding Neverland,’ ‘Man on Fire’ and ‘Feast of Love,’ which Robert Benton directed. She’s a really good actor and she’s beautiful. She fit the bill perfectly.” “Through the character of Jennifer Peters, the whole concept of identity is constantly in question,” says Mitchell. “It’s such an interesting character, or characters, to play. Who is Jennifer Peters? She is a character who sits at home in her stim chair, one we never really get to meet as a human. She has brown hair, bad skin, a big bum, funny teeth and stringy hair. She never wants to leave this enclosed reality that she lives in, so she experiences life through this robot, who is an FBI agent. We see her surrogate, who is also Jennifer Peters.

“It’s a little confusing, fascinating and it can be tricky to play a robot with the same voice and the same movement as your human character, even though the intent and motivation of that robot changes the characterization,” Mitchell continues.

“Your surrogate can look like whatever you desire,” director Mostow says. “For the sake of psychological continuity, most users choose surrogates which resemble their real selves in some way, albeit trimmer and better looking. The more adventurous may opt for completely different bodies—a new race or gender. Those with less money to spend can operate generic surries, which lack the facial detail and expressiveness of more expensive units.”

Rosamund Pike was tapped to portray Maggie, Greer’s surrogate-obsessed wife. “Maggie is beautiful, but sees only imperfections,” says Hoberman. “She wants to look in the mirror and see only beauty. For Greer, beauty is about what’s on the inside, not what’s on the outside. He fell in love with her for who she was, not for what she looked like.”

“Greer and Maggie are a very real couple who’ve lost a child, which he deals with by immersing himself in work, so she has to deal with it all on her own,” says Pike. “Because she feels so inadequate, her surrogate offers her perfection. Their interactions become all about two robots meeting, not the two real people.”

“Their relationship is the soul of the movie,” Hoberman adds. “We start off with two people who have gone separate ways in dealing with the death of a child—all during the advent of surrogacy.”

“The whole idea of surrogacy makes for a kind of kooky and original world,” says Pike. “It speaks on many levels about peculiar addictions and paranoia regarding self-image. On another level, it’s a very human story. Maggie and Greer’s relationship is at the heart of that struggle between perfection and reality.”

Pike says she saw Maggie’s surrogate as a “1950s air hostess—you know, Pan Am at its height with those little suits.” Her human counterpart was far less put-together. “You feel pretty vulnerable when you strip it all away to bring out all the imperfections.”

To embody the role of Canter, the mastermind behind the groundbreaking surrogate phenomenon, the filmmakers turned to two actors: James Francis Ginty portrays the youthful version of Canter, while James Cromwell serves as the older Canter.

“The whole idea for Canter is this aging guy with a debilitating disease who lives in a wheelchair, which also doubles as his stim chair,” director Mostow says. “And, the basic story is that Canter, who created surrogacy, believes it has gone beyond his original intentions.”

“Canter is not a messiah,” says Ginty. “In fact, I think his overriding motive was very selfless. Early in his life, he was afflicted with a dreadful condition. From that experience, he focused his energy towards bettering the world. So, he created surrogates to help people who were sick.”

“What an amazing thing to be able to give that gift to people that can’t live life like everyone else,” says producer Hoberman. “Canter thought it would help law enforcement and our soldiers so they wouldn’t have to die—they’d be safe while their surrogates got blown up in battle. But the technology got exploited when a big conglomerate took it over and made it for everyone. Canter feels the surrogacy technology has gotten out of hand.”

On the other side of the surrogate controversy is the mad seer who calls himself The Prophet. “He’s a fascinating character because he’s meant to be this kind of mythological figure that all these human beings follow,” producer Lieberman says. “He preaches pro-humanity, anti-technology, anti-surrogacy.”

The filmmakers called on Ving Rhames to portray the passionate character. “Ving Rhames is such a phenomenal actor and strong presence that he was perfect for the role,” says Lieberman. “He just emotes strength and leadership.”

Adds Hoberman, “Ving is powerful with a great voice. We also thought he would be a good foil for Bruce, too.”

“The Prophet is a cult leader who represents this faction of people who object to the use of surrogates, be it for religious or maybe even economic reasons,” says author Venditti. “These disenfranchised citizens don’t take part in the surrogate culture, so they live on the fringe in a place called ‘The Reservation’ where humans who’ve decided to disconnect from this technological world live.”

Rounding out the cast are Boris Kodjoe as FBI supervisor Andrew Stone, Michael Cudlitz as Colonel Brendon, and Jack Noseworthy as a local thug named Strickland who helps jump-start the story.

“In this fast-changing 21st century, where the technological changes of the Internet and all these things are happening at warp speed, there’s this generalized anxiety in people as to how to adapt in that environment,” Mostow says. “And this story about surrogates speaks to that. It becomes an allegory for life in the technological age. People identify with different aspects of the story immediately because they see it in their own lives.”

Making “Surrogates” A Reality

“SURROGATES” marked a homecoming of sorts for director Mostow, a Connecticut native who graduated from Harvard University 25 years ago.

In addition to mounting the film in several neighborhoods around Boston—the Leather District, the Financial District, the South End, Chestnut Hill, and the home of his alma mater, Cambridge, among them—Mostow also filmed in such Boston suburbs as Worcester, home to the FBI headquarters in the city’s shuttered downtown courthouse; Taunton—its abandoned Dever State Hospital mental institution doubled for The Prophet’s Reservation commune; and Hopedale, where the former Draper Mill loom factory was the site for the film’s more climactic moments.

Says producer Hoberman, “The interesting thing about Boston, from a filmmaker’s point of view, are these historic structures and buildings that were built in the 1800s. It has this classic American brick-and-stone architecture alongside these glass monoliths. And the one thing Boston’s done better than any city in the country is have it fit together. Our story is not really futuristic, but sort of in the present. And Boston, in its architecture, gives you that sense of both past and future, and we rode that line with it.”

To create this imaginative world pitting technology against humanity, Mostow recruited top filmmaking veterans, including production designer Jeff Mann and his art department, notably set decorator Fainche MacCarthy.

“One of the things I really liked about this movie was the wide range of looks and sets and locations and environments that we created and visited,” Mostow says. “In terms of all the looks and designs, we spent six months before we ever started building, just talking and conceptualizing, making sure that things were based in logic, which was satisfying both for myself and for our production designer, Jeff Mann. A lot of thought went into this, and a lot of really talented people did some great work.”

“This world is thrilling and interesting and visceral,” says Mann. “The graphic novel is a very moody, dark story set in this futuristic environment. In the movie, we set the story in a kind of parallel world. This technology of surrogacy is extremely advanced, but the surrogates in our story are tools. Their operators are absolutely responsible for the actions of this machine, just like you would do to any other machine.”

Mann designed several large set builds for the film, notably the DMZ habitat where a renegade band of humans have taken refuge from this technological world devoid of humanity and sensitivity.

There, one of the story’s central action sequences takes place in a mammoth maze of rusted, rotting shipping containers piled atop each other like huge building blocks rattled in a massive earthquake. An apocalyptic wasteland framed against a rotting loom factory abandoned three decades ago that provided a stark backdrop to a society that Mann calls “extremely bleak.” “The DMZ zone is a trashladen slum,” says Mann. “It’s a kind of commerce area for the Dreads, where they’re recycling or stripping copper wire. They use these things to barter with in the surrogate world for the necessities they can’t manifest for themselves in order to live in their isolated state.”

“The DMZ is this kind of war zone that surrounds the Reservation where the Dreads live and disconnect from society,” says Mostow. “It was full of burned-out vehicles and parts where these people try to make their living by manufacturing items that they can live on. This, along with the Reservation, were two sets in the movie that help make for a different experience for the audience.”

In stark contrast to this post-apocalyptic backdrop was the serenity of the Dever State Hospital, a sprawling, abandoned medical campus in far south-suburban Taunton that became the perfect setting for The Prophet’s isolated Reservation commune where the Dreads “sort of live life the way we probably did in the ’30s and ’40s,” says Hoberman. “A simpler life, without any technology, where humans farm their own food.”

“It had this urban quality to it that felt kind of city adjacent,” adds Mann. “It had an overgrown feeling as if reclaimed by nature. We put solar cells on the roofs and created these cisterns to affect the reclaiming of rainwater. We also planted vegetable gardens like public green spaces.”

The place where surrogates actually went for their own robotic facelifts was fabricated in Boston’s downtown Leather District in a chair manufacturing plant that became Maggie’s beauty salon in the film.

“Maggie is a beautician and the beauty in this world involves technology,” Rosamund Pike says about her character. “My beauty shop is almost like an auto-body shop. We’re doing blasting and sanding—industrial beauty is what we call it.”

Fainche MacCarthy’s crew dressed the set with power tools and belt sanders—all with dainty pink flowered handles. “There’s a scene where Rosamund has this beautiful woman who’s come in to get a face replacement,” prosthetic makeup artist Howard Berger says. “We built a replica of the actress that had a face that you could peel off. It was a very thin silicone face that fit over an endoskull over this upper torso of the actress. It’s a seamless blend of the actress talking, while the face is being pulled off, revealing the robot’s endo-skull underneath. Mark Stetson’s visual effects department pulled it all together.”

One of Mann’s eye-catching creations included the “stim chair,” the device from which humans neurally operate their robotic doubles. “The stim chairs were a challenge because I didn’t want them to look too dental,” Mann says. “It’s a comfortable, exposed lounge chair with these sensor devices that are supposed to articulate nerve reactions and other muscle stimulus.”

“The initial concept in the script for the stim chair was this very comfortable seat where you were attached to wires and electrodes,” Mostow adds. “We didn’t want something that felt claustrophobic, so I came up with the idea that essentially you are in something like a massage chair—which already creates a sense of relaxation. And there are lasers reading your skin temperature and reading your body movements and neural impulses. The only thing you have to wear is a very light headset that’s modeled on something like a Bluetooth. The idea was to create something one wouldn’t mind sitting in for 16 hours a day.”

To complement the stim chair, Mann also fabricated another key set piece—the charging cradle. “When you buy your surrogate, it’s shipped to you in this dual-purpose container that’s both the shipping container and the charging cradle for it,” Mostow says. “So, at the end of the day, you come home and you back into your charging cradle and plug in to recharge.”

The actual robotic look of the main cast and hundreds of extras appearing in the film came to life through the combined efforts of the film’s two makeup departments—the key makeup under the guidance of Oscar®-winner Jeff Dawn (“Terminator 2: Judgment Day”), and the special prosthetic designs courtesy of another Oscar winner, Berger (“The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe”). Because most of the main cast portrays two or more versions of their characters, Dawn and Berger utilized their many years of trickery to distinguish between the perfect surrogates and their rather imperfect human counterparts.

“The challenge for makeup and hair on this film from day one was determining what differentiates a human from a surrogate,” says Dawn. “Surrogates—are they plastic? Are they hyper real? Are they better looking than normal attractive people? The challenge was to make people who are already good looking look spectacular in every shot.

“The idea of surrogates touches on vanity that we all have, especially in this industry,” continues Dawn. “It touches on the technological advancements that we’ve made in the last few decades. You combine the two and you come up with a seemingly wonderful idea—the perfect man. I’ll make myself younger or taller or better looking.”

Dawn says that Willis had no trouble accepting himself in his own skin—even when the artisans added less-than-ideal details. “The human Greer character is a little older, a little rougher, a little more wrinkled,” says Dawn. “And Bruce was very good about that. When I needed to add a little age, some wrinkles, a salt-and-pepper beard, he was game for all of that. Now the surrogate Bruce had to be perfect, which we accomplished using a full head of blonde hair and these blonde eyebrows.”

Prosthetic makeup creator Berger needed to decipher the evolution of surrogates in his approach to designing a wide assortment of makeup applications and animatronic puppets for the film.

“There were a tremendous amount of challenges in trying to figure out how surrogates evolved,” he says. “I sat down with Jeff Mann and Jonathan to work out ideas, which presented us with many questions. Are they more robotic? Are they made of plastic or metal? Are their skins silicone? Are they something organic? Are they carbon fiber? The most important thing was what their endoskeletons were like. What’s inside of a surrogate? They’re all synthetic, made out of plastics and carbon fiber. Completely mechanical. Robots.”

Some of Berger’s unique designs included the crucified corpse of the surrogate Greer after it’s destroyed; shotgun wounds that graphically reveal the mechanical innards of the robotic doubles—KY jelly and green food coloring worked well as the hydraulic fluid that circulates through the surrogates; and eight animatronic “drone” puppets that operate the surveillance monitors inside FBI headquarters.

Casting Boston as the locale of this parallel reality created a challenge for the film’s visual effects gurus, here under the supervision of Oscar® winner (and three-time nominee) Mark Stetson. The film marked a homecoming for Stetson (honored in 2006 as one of Hollywood’s “Digital 50” content creators by the Hollywood Reporter and the P.G.A.), another Massachusetts native among the crew.

Stetson, who began his career 30 years ago, calls his role on “SURROGATES” a supporting one. “Our job was to help integrate the concept of surrogates into the everyday reality portrayed in the film. Because the movie takes place in the present, we tried to integrate some of the more advanced technologies in the story into everyday scenes to make everything look real.”

Making a perfect robotic version of a high-profile actor was a tricky business, he says. “The differences between the surrogate and its human owner/operator were established primarily with costume and makeup, live on the set,” Stetson says. “We enhanced those differences with VFX technologies beyond the limit of practical stage techniques by using a combination of 2D compositing and 3D CG techniques.”

Mostow also called on veteran cinematographer Oliver Wood (“The Bourne” trilogy), the longtime journeyman whose lighting and camera work enhanced the claustrophobic atmosphere of Mostow’s 2000 Oscar-winning WWII thriller, “U-571.” Emmy-winning costume designer April Ferry (HBO’s “Rome”) returned for her third project with the director, one in which she created dual worlds as illustrated by a combination of store-bought threads and custom-made clothing which vividly distinguished the state of surrogates versus that of humans among the film’s cast. The director also tapped veteran film editor Kevin Stitt, who cut Mostow’s big screen debut, “Breakdown,” over a decade ago.

Production notes provided by Touchstone Pictures.

Surrogates

Starring by: Bruce Willis, Ving Rhames, Radha Mitchell, Rosamund Pike, Ned Vaughn, James Ginty, Boris Kodjoe

Directed by: Jonathan Mostow

Screenplay by: Michael Ferris, John Brancat

Release: September. 25, 2009

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for intense sequences of violence, disturbing images, language, sexuality and a drug-related scene.

Studio: Touchstone Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $38,577,772 (63.7%)

Foreign: $21,978,582 (36.3%)

Total: $60,556,354 (Worldwide)