Lost Is Found: Greenlighting the Project

In 1940, producer Sid Krofft’s father snuck his young son into a movie theater to see the Hal Roach classic adventure One Million B.C. His life would never be the same. “This made such a huge impression on me, and ever since then I wanted to do a show with dinosaurs,” recalls Krofft. “That is where we got the idea for Land of the Lost.”

The television series Land of the Lost-the fifth show from creators Sid & Marty Krofft-debuted in 1974. Over three years and 43 episodes, young audiences grabbed their cereal bowls and eagerly followed the adventures of Dr. Rick Marshall and his children, Will and Holly. The park ranger, while on a routine canoeing expedition with his kids, fell over a waterfall and crossed a time portal…arriving in a land unlike anything TV viewers had ever seen before. Dinosaurs, aliens and all things past, present and future collided to keep children glued to their sets every Saturday morning.

Known for creating beloved series such as H.R. Pufnstuf, Lidsville, Sigmund and the Sea Monsters, The Bugaloos, Dr. Shrinker and Electra Woman and Dyna Girl, Sid & Marty Krofft attribute the success of their many shows, especially Land of the Lost, to one adage: Keep your concept simple.

Producer Marty Krofft explains: “We had ordinary people caught in this extraordinary land of creatures and three moons. We never lost track of how important the story was, and it was really important to us to give names and personalities to the dinosaurs-the first time dinosaurs were ever on television.”

Land of the Lost began its journey from small to big screen several years ago. Producer Jimmy Miller approached the writing team of Dennis McNicholas and Chris Henchy about translating Sid & Marty Krofft’s classic show into a feature film, with an eye for Will Ferrell to star in the project. Miller, who manages Ferrell and Henchy-as well as the Kroffts-knew that McNicholas and Henchy had the comic sensibility to make the project work as an action-comedy.

For more than a decade during their time together on Saturday Night Live, McNicholas had written for and with Ferrell, and the Krofft brothers were invaluable contributors in elaborating upon the intricate back-story as the team reimagined the world of Land of the Lost.

Remembers McNicholas: “I’d been jockeying for this job for the last 18 years. I had the Land of the Lost lunch box when I was in kindergarten. When Adam McKay, Will and I were at Saturday Night Live, we made Sleestak jokes as frequently as possible. I jumped at the chance to work on this.”

His writing partner has similar fond memories of the show. Says Henchy: “I watched it as a child. My parents constantly told me on Saturday mornings to turn the TV off, so it’s been brewing for years as well.”

Die-hard fans of the property, the writers were adamant about respecting the series, but also updating Land of the Lost so it wasn’t a paint-by-numbers interpretation. They reintroduced Marshall, Will and Holly as three unlikely adventurers who must band together to survive in a surreal world.

“Using our childhood Land of the Lost memories as our guide, we tried to have fun with the full cosmic complexity of the series and not limit ourselves to just dinosaur jokes,” provides McNicholas. Knowing that Ferrell would be the film’s lead allowed them to push the comedy limits.

Not only did the partners believe it would open up the comedy to change the characters from a family to three strangers forced to work together, they knew that the film needed to have all the constructs of an exciting action adventure. Says Henchy: “Our mantra was that if you stripped away the comedy, it would still be a good adventure and vice versa. That was important to us.”

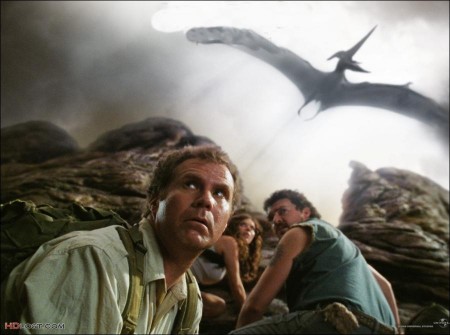

After initial discussions with his team, Ferrell was certain he wanted to be a part of the project. He explains: “Hands down, Land of the Lost was one of my favorite shows as a kid. When you think back to Saturday morning television in the ’70s, it was mostly Bugs Bunny and crazy cartoons. Then you had this realistic live-action show with a dad and two kids and dinosaurs and all this crazy stuff that was played as real. Of course, the effects looked amazing to my nine-year-old eyes.”

“The big question was,” continues Ferrell, “Did we go the route of the television series and show Sleestak where you can see the zippers up their backs, or do we take Jurassic Park and thrust comedy into it?” Fortunately, a meeting with a longtime colleague would resolve that question.

In spring 2007, old friends Ferrell and filmmaker Brad Silberling sat down for lunch. Ferrell told Silberling he was attached to Land of the Lost and wanted him to be involved. The director, who had several years earlier completed another large-scale adventure with Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, had his own fond memories of Marshall, Will, Holly, Chaka and the Sleestak.

“I’m the age where I watched Land of the Lost on TV in my pajamas every Saturday morning,” says Silberling. “It sounded like a completely brilliant idea to make it into a movie. That you could be ballsy and go for it, taking the things you love and combining them with humor, were just the right ingredients.”

The director felt it was important to respect the original property while writing a new chapter for the world of Land of the Lost. “You have to venture bravely into an undertaking like this. I was a dedicated viewer of the series as a child, and I had my own emotional response, so I feel I am a good ambassador,” Silberling notes. He knew if he were to agree to the film, the cast and crew needed to share “a sense of humor about what the experience of the original show was” and understand that “Saturday morning television had its limitations,” as he recalls Sid & Marty Krofft saying.

Silberling met with Universal executives about helming the film and noted that if he was going to be involved, he wanted to use practical sets for as much of Land of the Lost as possible. The deal was signed, and stages on the Universal Studios lot were immediately reserved. By summer 2007, four-time Oscar-nominated production designer Bo Welch came aboard and set construction was soon in full swing on six sound stages.

As was Ferrell, Marty Krofft was quite pleased with the choice of director. He commends: “Brad Silberling has a very large heart. He has passion; he’s a pro and a stickler for detail. He was into every little corner of this thing…every nook and cranny. He’s just calm; he’s got a great attitude.”

The filmmaker worked with the screenwriting partners to hone a Wizard of Oz-like model for the story in which audiences would be whisked away with Marshall, Will and Holly to a faraway land. They blended that concept with elements of a Swiss Family Robinson experience in which the characters are forced to make their new home in another world. So what makes that funny? Says Henchy: “You can’t lose with comedy versus jeopardy…when you layer that with adventure.”

Recasting Marshall as a discredited “quantum paleontologist”-an imaginary discipline that blends particle physics with the study of dinosaurs-lent itself to the sci-fi bend of the show. Many of the writers from the original series also had written for Star Trek in the ’60s and went on to become successful sci-fi novelists. Says Ferrell: “Our characters think aloud with the audience as they are stuck in these absurd situations, and that is what makes it so fun. The scale is just tremendous in every way, from the sets to the visual effects. Marshall is a fun character to play because he is the take-charge leader of the group…whether he is capable or not.”

Subtle nods to the series are seen throughout the story. Shares Silberling: “To play and enjoy with key elements of the series, that is what made it interesting to me. To be able to access this world via Will and the other outrageously talented cast, that was reason enough for me to go through the war that it is to create a big production. I wanted to be in that world.”

Casting the Routine Expedition

Production greenlit, it was time to cast the additional roles that would allow Dr. Rick Marshall to embark upon his epic adventure. To move the comedy adventure along, Silberling believed the script needed to show conflict among our trio of adventurers as they fumbled their way through the foreign land. “We created a group of characters much more impaired than the TV series,” he says. “We have three misfits needing to prove themselves and, in the process, they have to save the Earth.”

Holly would no longer be a little American girl with blonde pigtails, but a British expatriate who has been educated at Cambridge and moved to Los Angeles for work. She has been hired as a research assistant at La Brea Tar Pits, and her decision to seek employment there is more than coincidentally based on her attraction to Dr. Rick Marshall and (what she considers) his brilliant mind.

Explains Ferrell of his character’s relationship with the fellow scientist: “Marshall is misunderstood and considered a joke in the scientific community, since he thinks there is an alternate universe. We see him down and out working at La Brea Tar Pits… until he meets Holly, who believes in him and his work.”

Silberling and Ferrell were determined that a British actress would play Holly Cantrell in the film. In fact, when actor Anna Friel was cast, Silberling insisted that she speak in her distinct Manchester accent. “On Pushing Daisies I had an American accent, and most other projects I have had to speak with a posh English accent,” explains Friel. “This is the first time I have used my own voice since I was 20.”

The performer enjoyed portraying the only person on Earth who still believed enough in Dr. Marshall to focus her graduate work on his theories of quantum paleontology. Friel continues: “She has a huge crush on Marshall and his mind, and he doesn’t realize she is totally in love with him.”

When she was cast, Friel wasn’t familiar with the Land of the Lost television series. Silberling liked the fact she had a fresh take on the character from the first table read. “Anna just commits,” he compliments. “You believe her belief in Marshall, and she goes for it. She has a great spirit.”

It helped matters that Friel was trained in classical dramatic improv. Per Silberling’s direction, she had no problem jumping into improv mode with her three co-stars. One of her biggest challenges on the set was controlling her laughter. She says, “I had to practice not laughing during a take. The boys would go off on a tangent, and I would do everything in my power not to laugh-including practicing my yoga breathing.”

When casting the part of redneck huckster Will Stanton-a constant thorn in Dr. Marshall’s side-the filmmakers looked to a performer with whom two of them had previously worked. In 2006, Ferrell and Land of the Lost executive producer Adam McKay saw comic actor Danny McBride in Jody Hill’s dark comedy The Foot Fist Way at Sundance. It was a small independent film that immediately resonated with Ferrell and McKay, and they signed on to release it theatrically through their company, Gary Sanchez Productions. Prior to beginning photography on Land of the Lost, McBride had also locked in scene-stealing roles in Pineapple Express and Tropic Thunder and agreed to star in the HBO television series Eastbound & Down.

Silberling found an everyman quality to McBride-a trait he shares with Ferrell-that allowed the actor to be coarse, yet still charming, as the manager of Devil’s Canyon Mystery Cave. He felt that McBride could do most anything on screen and audiences would still find him sympathetic…and love going along for the ride. Commends the director: “Danny is unbelievable; he feels like a found object. He does not seem like a guy that just walked out of a comedy club in Hollywood…more like a guy that just dropped in from North Carolina who happens to be incredibly funny.”

Ferrell is used to having others be the straight man for his wild antics on camera, but he found it refreshing to work with an actor who allowed him to occasionally switch roles. Says Ferrell: “We trade off in this film. I go between competent scientist and bumbling scientist, and Danny and I pass the ball back and forth.”

McBride jokingly says of the film’s star: “Audiences like a sexpot. They like somebody who exudes sexuality, and that’s definitely what Will does. Everything from the socks hiked up to his knees to the vest that’s littered with trinkets and trophies from past conquests in quantum paleontology. This is what the ladies are looking for.”

The team knew there could be no Land of the Lost film without a certain ape-boy named Chaka creating mischief in the fantastic world. Laughs Silberling: “Chaka freaked me out as a kid. It was a combination of the makeup and the fact that there was a kid under there.” Drawing from those memories, Silberling’s makeup and prosthetics team created what he refers to as “a character who is sketchy but loveable. He is a con man with heart.”

Cast as the Pakuni missing link was fellow Saturday Night Live writer and performer Jorma Taccone. It was a role Taccone had been unknowingly preparing to tackle for years. “When I was a kid,” the actor explains, “we used to role-play Land of the Lost. I always ended up playing Chaka because I was the shortest. Plus, I looked like a freakish monkey-boy; that was the other reason. I’ve been preparing for this role my entire life”

McNicholas and Henchy had written Chaka as a devious ape-boy, an opportunist who will do anything to survive…including putting Marshall in harm’s way. In addition to McBride, Ferrell would need to juggle another comedy antagonist. About working opposite his co-star, Taccone says: “Will and I had never met at SNL, but just knowing he had worked on the show, I figured we would get along. There is nothing in the world like working on Saturday Night Live…not one single thing.”

“Chaka is a bit of a rascal throughout the film, but in the end we come to an understanding,” adds Ferrell. “Marshall wants to think it is a master and servant relationship, but that is the farthest thing from Chaka’s mind.”

Silberling liked the idea of throwing McBride’s character into the trenches with Chaka, and upping the comedy as the two of them ganged up on Ferrell’s Marshall. “The trick was to get a guy who is the opposite of Marshall and Holly-a man with no science skills who is also a companion for Chaka,” he says. “Will and Chaka become a team in this movie.”

To get ready for filming, every day he was on camera Taccone spent three-and-a-half hours in makeup and wardrobe with Spectral Motion artists, who created the suit and prosthetics. First, his facial makeup prosthetics would be applied, and then he would slip into the hairy suit made from a combination of yak, angora and human hair-all sewn in strand by strand to a spandex liner. Finishing touches included latex hands and feet, as well as custom-made bucktooth dentures. A team of five Spectral Motion artists made two suits-custom fit to Taccone’s slim physique-that were used during the duration of filming. Each suit took six weeks to construct.

Chaka speaks his native Pakuni language in the film. During shooting of the Land of the Lost television show, brilliant UCLA linguist Dr. Victoria Fromkin created the Pakuni language especially for Chaka. She designed a 400-word dictionary as a guide with which the original Chaka could work.

At the time Taccone was cast in the role, there was no written dialogue for him in the script. Whenever Chaka appeared, the script would read, for instance, “Chaka grunts.” The performer decided to take it a step further. “I tried to be super strict about using only Pakuni words from the original series, but I still had to make up a bunch of stuff. At the first table read, no one knew what I was saying but me. It kind of freaked people out, but we ended up using all of it.”

Sums Marty Krofft of the experience working with this talented cast and crew and his hopes for fans new and old: “This project came together with a lot of love. We are very lucky our fans are still with us after all these years. We hope they are as proud of the film as we are and that a whole new generation will too learn about Land of the Lost.”

Sleestak and Altrusians: Humanoids in Land of the Lost

Just as important as Chaka’s role was the appearance of another series favorite: the Sleestak. In the ’70s, children across the country were haunted by the serpentine sounds and deathly slow marches of these reptilian humanoids. Recalls McBride: “I was afraid of the Sleestak as a kid, and how they moved and hissed. It was wild to see them in person after those childhood memories.”

In the TV show, Sid & Marty Krofft had the Sleestak played by three extremely tall performers who were actually USC basketball players. They were dressed in pajama-like jumpsuits with visible zippers that went up the backs of their costumes. Constantly on the hunt for Marshall, Will, Holly and Chaka, the Sleestak were always prepared to strike.

For the filmmakers, it was important that the Sleestak not be CGI characters, but actual actors in costumes. Like McBride, Silberling admits, “As a kid, they freaked me out when they moved so slow.” That sense memory proved to be good training for the future director. He offers: “Doing the Sleestak practically is a wink and an acknowledgement to the series. Sid & Marty had no room for the villains to chase on the small 30-foot stage at Warner Hollywood back in the ’70s.”

Sid Krofft extrapolates: “We didn’t have much money to work with back then, and there were only three Sleestak in the series because we were just on one soundstage. The impression to the viewer was that there were many more. We want the Sleestak to scare the hell out of audiences in the movie…just like they did in the television show.”

Four months prior to principal photography on Land of the Lost, Spectral Motion built 30 custom Sleestak suits from foam latex. Each skintight suit weighed approximately 30 pounds and was slipped onto the actors only after they were coated with K-Y lubricant. The performers are tall to begin with, but the five-inch-heeled boot inside the Sleestak suits elevated them to seven feet. To add to the individuality of each member of the collective, every Sleestak head was made from a custom cast of his performer’s head. The finishing touch to their look is the signature dark, dome-shaped and bulging eyes.

Sleestak are known for their pinching webbed claws, complete with vein and membrane detail. The grotesque, snap-on toenails added another 12 inches to the length of the performers’ feet. To compensate, production designer Welch had to lengthen the staircase treads in the oddly shaped Pylon Plaza (where transportation to other worlds can occur) and Sleestak Temple Plaza sets.

It was challenging for the director to work with the Sleestak on set. As it was so physically taxing for the performers inside the suits, the filmmaking pace was slow. It required two techs to be on set with each Sleestak during their workday; the assistants had to suit them up, hydrate the actors and tend to them during filming. The performers had little to no vision while they worked, and the temperatures inside the suit-especially under the lights-were difficult to grow accustomed to. In fact, the heads couldn’t be left on the Sleestak talent for more than 10 minutes at a time.

It was especially a challenge for stunt coordinator DOUG COLEMAN to choreograph fight sequences involving the Sleestak. Says Coleman: “It was challenging to work with the Sleestak in their costumes. Their visibility was nil, so when they were reacting to punches, it was very much like looking through wax paper. But we made it work.”

Most of the Sleestak movements-such as opening and closing their mouths, walking and claw pinching-are all actor-driven. However, such motions as spines rising up and toenails clicking were remote-controlled and puppeteered off screen.

Spectral Motion artists were also responsible for creating the suit for Enik the Altrusian, an intelligent, English-speaking Sleestak who first appeared in the third episode of the television series. As Enik’s head was filled with animatronic motors that were controlled by a dedicated puppeteer, his head alone weighed more than 13 pounds.

The core of this head was made of fiberglass taken from a head mold of actor JOHN BOYLAN, who portrays Enik. Foam latex was then applied over the fiberglass and intricately painted to achieve a lifelike effect. Inside the fiberglass encasement is an aluminum frame that houses the requisite motors.

Since Enik is more evolved than the other Sleestak, his animatronic head expresses much more emotion. He comes complete with a furling brow, ability to squint and lips that move intricately. His head also had a built-in fan located in the mouth that cooled off all the mechanical working parts…as well as Boylan inside.

Enik’s large dome eyes are four inches in diameter and coated with a holographic reflective film in the center that creates an open-cell membranous look. Notes Silberling of this interloper: “Enik was incredibly selfish in the TV series. We have run with that and then some. I think fans will love the direction and leap we took with him.”

Building custom suits for the Sleestak and Enik was a pricey endeavor. “It is no different than building a couture gown,” says Spectral Motion owner Mike Elizalde.

As Enik is the only Sleestak who wears clothes, costume designer Mark Bridges designed a multilayered tunic for him. Says Bridges: “The first layer is painted and foil-leafed, and then a fabric is underneath, and then a black netting is over that. What you get is a look that is constantly changing.”

Production designer Bo Welch had long been fascinated with the source material for Land of the Lost. When he signed on to conceptualize multiple worlds that had crashed together, he knew a massive design challenge lay ahead. Says Welch: “The fact that it was another dimension was always in my brain. Even though a tree was a tree or a cave was a cave, I knew I would exaggerate it slightly and stylize it so that it had its own flavor.”

At the height of production, Welch and his art department team occupied six soundstages on the Universal Studios lot, making the film the largest Universal Pictures production ever to be filmed there. The size of the task at hand, however, didn’t intimidate the fastidious director. Notes Silberling: “Things still feel very much homemade on Land of the Lost, just on a much bigger scale.” Fans of the series will notice sets such as the Home Cave and the Stone Crevasse Bridge look similar to the landmarks of the series.

Silberling and Welch took some of the more interesting earthly elements and mixed them up in strange ways. While infusing enormous scope and scale into the production, they had to take into account CGI dinosaurs would be traipsing through their sets. “There is nothing funny about these sets,” says Welch. “The more real you make them, the more seriously you take it, and the more grounded you are in the story.”

One of the reasons Silberling wanted to shoot so much on stage was to allow Oscar-winning cinematographer Dion Beebe tight control of the lighting. Says Beebe: “Practical sets ground the storytelling. It’s an interesting choice that Brad made, because we’re in a day and age where environments can be created completely artificially. Yet Brad went the completely other direction-to not rely completely on the fabricated post environment. It’s a little bit old-fashioned. There were big sets and big lighting setups every day.”

To accommodate the production schedule, Land of the Lost sets turned over quickly, which proved to be a timing challenge for all involved. Offers Welch: “If we didn’t finish a scene and move off a stage, then we couldn’t turn the set around to the next design…and that would affect the next set being built, and the next one. It was nerve-wracking to say the least.”

Veterans on both sides of the camera were impressed. “It was a first for me to work on a movie with such massive sets,” recalls Ferrell. “In a way, it is a throwback to the old Hollywood stage movies. I loved every second of it. Every few days we would move to a new set that was even bigger and better than the last.”

Welch and his art department worked around the clock to create the worlds. It was constantly on their minds to embrace iconic images from the show, but update them as a 2009 translation. “It was endearing when you look at the TV series and how they would take these big concepts and execute them with the budget and technology they had available at the time,” commends the production designer. “That is what gave the series its quirky charm.”

On Stage 27 on the Universal Studios lot, the art and construction department repurposed rock faces, trees and mossy surfaces to create three distinct huge set pieces: the Forest, the Pylon Plaza and the Sleestak Temple Plaza. These three sets were the largest in scale that were built for the film.

Working with only a month of prep time in between each of the three sets, the team constructed rock walls, 40-foot-tall trees, stone floors and gnarled roots-only to recycle and rearrange them to create a new look for a new set.

The Pylon Plaza stone set was created to resemble ancient temple ruins. With steep staircases and exposed moss and tree roots, the Plaza was surrounded by imposing columns and mystical archways that allow audiences to imagine what might be lurking among the decay. Fifteen-foot-high Sleestak head sculptures rested like bookends on the ground floor, and hand-painted beneath them is: “Beware of Sleestak.” Silberling remembered that detail from the series and couldn’t resist including it in the film.

The Sleestak Temple Plaza houses the Library of Skulls, a public forum where Sleestak elders of days gone by could speak their wisdom. A similar concept to this set existed in the TV series. Nine smooth, whitish-gray pods hold the imposing Sleestak skulls-heads that are illuminated with flaming red eyes set against a bright green background. This visual, when paired with a caged Holly swinging over a flaming bottomless pit, makes for an exciting and comical stunt.

Stage 12, the largest on the Universal lot, was the setting for the Home Cave set where Marshall, Will, Holly and Chaka seek refuge from a T. rex named Grumpy. Reminiscent of the Home Cave of the series, with red rock walls and an opening just large enough for Grumpy to get a peek inside at his prey, this cave morphed into the sparkling mossy Crystal Cave where Marshall and Will spy on a more intimate side to Sleestak existence. Also shot on Stage 12 was the Feeding Station where Grumpy waited for his next meal, and the Crevasse set where baguette-shaped rocks serve as escape bridges from Grumpy-who keeps hot on the heels of our unlikely heroes.

On Stage 12, enormous 32-foot red rock walls were constructed for the cliff face. The 28 sculptors working on the film handcrafted each nook and cranny in the rock. Using saws, picks and thick, hot gauge wire, these sculptors took large rectangular blocks of Styrofoam and shaped and sanded them until they achieved the desired results. The Styrofoam was then sprayed with a thin layer of plaster and painted in various mixed earth tones. When finished, they created an environment that makes the visitor feel as if he or she is walking through the Grand Canyon or hiking around ancient ruins.

The interior of the Devil’s Canyon Mystery Cave was constructed on Stage 29 on the backlot. This is where Marshall, Will and Holly would take a raft ride through Will Stanton’s cheesy tourist attraction when the greatest earthquake ever known hits. As they fly over the rapids, they are pummeled over the cataract into the Land of the Lost.

The Devil’s Canyon Mystery Cave tunnel was built to stretch across 200 feet; upon completion, it was filled with 40,000 gallons of milky water. This winding cave-complete with ceilings that were 13 feet high-housed three-and-a-half feet of water. To make it waterproof, the floor of the set was sprayed with rubber coating known as a Rhino liner, and a track was built on top of that to carry the raft. As the earthquake hit, MICHAEL LANTIERI and his SFX team pumped water through at 10,000 gallons a minute to create fierce Class 5 rapids. Says Lantieri: “The pumps we used were so powerful they could empty a swimming pool in one minute flat.”

Wearing rubber boots and waders, the crew was right alongside the cast in the waist-deep water. But it was our heroes who got the full brunt of the aquatic blast. Laughs Friel, “It was a challenge for Will, Danny and I to stay inside the raft when the rapids were going full force…not to mention our getting soaking wet.”

To take full advantage of this set and extend the travel distance, the crew shot in one direction of the cave during the day, and then LAURI GAFFIN and her set decorating crew came in to switch things up. Overnight, her team redressed the cave so Silberling and Beebe could shoot the raft as it traveled in the opposite direction the next day.

The Caldera (large crater formed by a volcanic explosion) set was built as a 360-degree circular set on Stage 28, complete with removable walls. The illuminated floor was coated with yellow molten lava that housed 100-plus handcrafted dinosaur eggs on pedestals. The set was filled with smoke, as well as eggs ready to hatch at any time…while Marshall makes some curious music with his Tachyon Meter.

On Stage 42, the interior Pylon set was built. While during the TV show’s run the cast would walk inside a gold foil box to enter the Pylon, Welch knew he would have to design something a little more, erm, state of the art, for this iteration.

A black-box set was designed to showcase the crystal console and control board-an intricate setup that is the only hope for Marshall, Will and Holly’s escape to their home dimension. To create, Welch’s team blacked out the room in dark cloth and raised the set on a two-ply Plexiglas platform that was five feet in height and illuminated underneath by 800 bright lights. To achieve the desired mystical effect of the console, one layer of the Plexiglas was solid and one was cracked. The lights created such a large quantity of heat that big fans were used to keep the area underneath the platform cool.

“All the other sets on stage were very textured with trees, rock and vines-very bristling and alive, rippling with presence,” offers Welch. “The Pylon was just the opposite. It’s serene, clean and minimalist with crystals. We gave it a deliberate contrast, so you feel like you are in limbo.”

In Land of the Lost, Marshall works at the world famous La Brea Tar Pits in the Miracle Mile section of Los Angeles. The storied Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits represents the only active urban paleontological excavation site in the United States.

On the Universal backlot, the art department recreated an office for our discredited scientist that was set under the Page Museum. This cluttered environment contained dinosaur bones, trophies, diplomas and magazine covers that feature Marshall in his heyday as a paleontologist. The set decorating department worked closely with La Brea Tar Pits staffers so that his office looked authentic and paleontologist references were realistic. Sticklers for accuracy, it even ordered the production’s bone replicas from the same place that La Brea Tar Pits does business.

Sid & Marty Krofft were amazed to see the world they imagined more than three decades ago come to life as an enormous production. Reflects Silberling: “I have truly loved having the Kroffts on set every day. They are like the fairy godfathers of the project. I love to see the look on their faces when they are seeing these ideas realized, especially using technology they didn’t have then. Having them around makes me feel connected to the show-one that blew my imagination open as a nine-year-old.”

Pinnacles, Dunes and Tar Pits: Shooting Off the Lot

Though a lion’s share of Land of the Lost was lensed on the Universal backlot, it was important to the filmmakers that they capture scenes on location wherever it made the most logical sense. Offers designer Welch: “It’s important on a movie like this, when there is so much stage work, to sprinkle a bit of location so that you have a sense of wide open spaces and air.”

Land of the Lost was fortunate to be granted access to film exteriors at La Brea Tar Pits and its Page Museum. These locations included the famous black bubbling tar lake on Wilshire Boulevard at Curson Avenue, which had never before lifted its fence for a film crew.

As dynamic as the interior of the Devil’s Canyon Mystery Cave set was on stage, equally interesting was the “exterior” of the cave that was shot on location in the desolate flat fields of Lancaster, California, at Avenue I West and 110th Street West. Devil’s Canyon is where we meet Will for the first time, and we find him running a cheesy roadside tourist attraction and gift shop.

It took the production design team a month and a half to construct the exterior opening of the cave, in which the curious adventurer enters via raft through the devil’s head, complete with red, bug eyes and jagged teeth. Also built at this location were the tacky gift shop-selling everything from T-shirts to gemstones-and trailer that Will called home. With 60-mph winds sweeping through the plains on a regular basis during construction, this build was not as easy as it might look.

North of Baker, California, on Highway 127, Dumont Dunes-known for its beautiful white sands, blue sky and off-road recreation-was where the crew filmed next. To depict Marshall, Will and Holly’s extreme arrival in the Land of the Lost, the production team lensed in the middle of the dunes in extreme heat. From the base camp of trucks and trailers, cast and crew were given the rides of their lives as they were transported to set in dune buggies.

Treacherous winds that create the amazing shifting sands and 400-foot high dunes reach up to 50 miles per hour at Dumont Dunes. And though the visual effects department removed all traces of the crew in the final product, during filming the greens department was tasked to cover up non-Marshall, Will and Holly foot traffic by using rakes and leaf blowers.

Equally challenging was filming on location in the unearthly Trona Pinnacles, in the California Desert National Conservation Area, where massive sharp rock formations are most unusual. Upon arriving in the Dumping Ground in the Land of the Lost, the reluctant visitor finds everything from the storefront of an Urban Outfitters and a bust of Bob’s Big Boy to a red English phone booth and a Hummer limousine. This rough and rugged terrain became the stage for a very rowdy dinosaur chase.

Trona Pinnacles can be found on special national park land supervised by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The BLM monitored crew activity closely to make sure the production followed strict environmentally safe guidelines and left nothing behind but footprints. One of its conditions of filming was that if the endangered desert turtle happened to roam into the area during shooting, all filming would have to cease. Fortunately for the case of production, that never happened.

On the salt flats near Trona Pinnacles, the team built one of the most amazing sights seen during a production that was full of them. A retro motel was constructed, complete with neon signs and a 40′ X 15′ X 7′ swimming pool; the structure was half sticking out of the ground in the middle of nowhere. While the intention was for the pool to be half-buried in the ground, that was not so simple to execute. The construction crew found that when it dug into the salt flats, water with a high salt content was bubbling just below the surface. Even when the swimming pool was filled with fresh water and stuck in the ground, it had a tendency to pop up…due to the high levels of brine.

Getting Grumpy: VFX in Land of the Lost

For the Land of the Lost series, the Kroffts created 40 minutes of stop-action dinosaur animation that was repurposed over the three-year run and used many times. That was the first time video and stop-motion were combined and used on television.

Much to the pride of this team, the film is also using groundbreaking technology to create visual effects; as always, photorealism is the goal. “This is not `a routine expedition’ for us in VFX,” puns Oscar-winning VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer. “We are responsible for many things in this film…from creating key characters like dinosaurs Grumpy and Alice to extending the sets and Sleestak armies.”

Naturally, Westenhofer and his team at Rhythm & Hues were heavily influenced by Jurassic Park and the benchmarks set 16 years ago for dinosaur design. With the tools they had in front of them, however, they were determined to take the Land of the Lost dinosaurs to a whole new level…especially for Marshall’s cunning antagonist, Grumpy. Explains Silberling of the T. rex’s motivation: “It’s Moby Dick. Grumpy is obsessed with Marshall and will stop at nothing to track him down.”

Logically, the Rhythm & Hues team began designing Grumpy by using existing illustrations of T. rex. Combining some of these characteristics with nontraditional ones separated Grumpy from the pack. For example, little horns were added on the back of his head. A 3-D model of Grumpy was then sculpted and scanned into the computer. Creating movements such as arm placement that will show actual wrinkling, the animators began working on the endless details it took to make him photorealistic.

Grumpy is a fully functioning character in the movie that interacts with the other actors, so he has to have a personality. Laughs Ferrell: “Outside of The Flintsones, I think this is the first time you see a dinosaur vindictively pursuing a character.”

Ferrell, Friel, McBride and Taccone found their imaginations put to the test when they shared scenes with Grumpy. In place of the carnivore, one of the digital technicians would hold a 16-foot pole to serve as a marker for the performers.

Nicknamed “Grumpy on a Stick” by the crew, the setup had a brightly colored ball on the end that allowed actors to find their eye line.

Shooting in the Land of the Lost Dumping Ground while they were on location in the vast Trona Pinnacles near Death Valley, California, also proved difficult for the VFX team. This set is where the dinosaurs come to feed and where the Grumpy chase sequence begins. “The Grumpy chase, when he is in active pursuit of Marshall, is huge and was a really hard challenge for Rhythm & Hues,” notes the director.

Continues screenwriter McNicholas: “This chase is a huge chunk of the script. When I went to the desert and saw how Brad had set this up, I was amazed. It was incredibly elaborate, packed with jokes and information.”

From shot to shot, it was a constant concern for Silberling, Beebe and VFX supervisor Westenhofer to make sure there was enough room on the screen for the dinosaurs. “It’s challenging to make sure you have space in the frame when you have a 40-foot-long animal,” notes Westenhofer.

Improv on Land of the Lost didn’t exist only on stages and locations. It also happened in the digital world. Recalls Westenhofer: “One of my favorite moments is when Will Ferrell chose, on the fly, to fist bump Grumpy. This will be the first time on the screen you shall see a person do this. It will be hysterical.”

Throughout the story, the cast interacts with dinosaurs. Both on land and on wires, it proved a tremendous challenge for VFX to marry images of real people interacting with CGI characters. To ensure authenticity of look, Westenhofer worked closely throughout production with DOUG COLEMAN and his stunt team to get the exact angles he needed. When a stunt using people was taken as far as it could be taken, the VFX team jumped in to extend the action.

At one point in the film, Marshall must hop onto Grumpy’s back and take a ride. As this visual effect combines both stop-motion and motion-control rigs, the scene was quite complicated to pull off. Prep for this sequence began a month before shooting, with a nine-person crew from Rhythm & Hues operating the high-tech computer and camera gear on set.

To capture the motions of a prehistoric ride, Ferrell was placed on a mechanical saddle that was programmed to move in different directions. So the filmmakers could get a rough sense of the scale of the final product-and see what was happening on the spot-the computerized pre-viz image of Grumpy was laid on top of the live visual feed.

The dinosaur and creature action in Land of the Lost does not stop with Grumpy. From showtune-loving baby pterodactyls that hatch out of eggs and thousands of spiders that crawl out of fruit given to Marshall by Chaka, to a giant crab that gets cooked, the VFX team had more than enough work on its hands.

Signature action pieces, such as the raft falling over the Devil’s Canyon waterfall when the earthquake hits and Marshall, Will and Holly passing through time and space into another universe were handed to Rhythm & Hues to create digitally. Even more challenging, they had to seamlessly retain the comic elements of the film as they designed the environments.

Indeed, an entire world-from the dirt on the ground to the three moons of the sky-was created from the bottom up. Extending backgrounds where the sets end and creating a landscape for the Land of the Lost flora and fauna took much creativity and manpower from all involved in the project.

During an 84-day shooting schedule, one week of shooting in which the VFX department was in total control took place on a blue-screen stage. When principal photography wrapped, Rhythm & Hues switched gears to full throttle as 150 artists were brought on board to finish environments, imagine dinosaurs and add the most intricate of details for the world that time forgot.

Butt-Molds and Fast Punches: Stunts of the Action-Comedy

This constant pursuit of our heroes by Grumpy led to some physically demanding days for the cast. The principal players wore harnesses for a week and were hoisted 30 feet into the air as they were snapped up by man-eating vines inside Grumpy’s feeding station. Take after take, they dangled over a pile of more than 300 handmade bones, gaining momentum (and soreness) when they joined hands and swung back and forth.

To add to the glamour, prior to shooting on location in Dumont Dunes, the cast was fitted with butt molds. These molds were crafted in plastic and hidden under their costumes so they could easily (and rapidly) slide down the steep 45-degree-angled sandy hills without hurting their respective posteriors in the process.

As Dr. Rick Marshall, Ferrell was required to engage in multiple stunts. From saving Holly by jumping onto a swinging cage raised above a deep pit to being thrown aloft by Grumpy, the maneuvers were challenging for the comic performer. Even though he was harnessed and had rehearsed with the stunt team, it was still a bit scary. “Out in the desert at Trona Pinnacles, they rigged this crane and pulleys that hoisted me 30 feet into the air…as if I was being picked up by my backpack with Grumpy’s teeth,” says Ferrell. “Fortunately, we got it in one take, because it would have taken a lot of psyching up to do that again.”

As his character was scripted to fight Enik the Altrusian while on high wires, Danny McBride also learned to get comfortable above ground as well. This was also the first big action-movie experience for Anna Friel who, among other things, became skilled at swinging Holly’s leather belt as a weapon against the Sleestak.

Jorma Taccone also had his share of physical challenges. He had to learn primate mannerisms that included walking while staying hunched over and running while using his hands as well as his feet. To get into character, Taccone watched National Geographic Channel DVDs. When it came time to suit up, however, he realized he had no idea how tough it would be to maneuver in that posture.

While Holly and Will are not brother and sister in the film, they bicker just as much as they did on the show. Though McBride and Friel had it down to a science, sometimes the play fights got a little out of hand. Recalls Friel: “Danny would joke that during the fight sequences I was dangerously close to clocking him in the eye. During one take, I did hit him a bit, but he said he was fine. Unbeknownst to me, he went to his makeup trailer and came out with a big black eye and bleeding. I never felt so bad. He milked it for all it was worth, and good on him.”

Contests McBride, who says he was indeed walloped by his co-star: “Anna will say that clocking me was an accident. She will say that I was in her way. But if you review the tape, you’ll see that she is lying through her teeth. And it was a hard hit. I’m not going to lie. Almost brought a tear to my eye, but I had to keep cool and you know, act like it didn’t hurt.”

The 2nd Greatest Earthquake Ever Known: Props and Effects

Michael Lantieri and his special effects team of 25-plus were handed the arduous task of simulating a major earthquake at the Sleestak Temple Plaza that threatens to annihilate the Land of the Lost and all its denizens. The effects included having tons of simulated heavy debris fall about our heroes.

One of the big-ticket items used was nicknamed the “Weber Pod” (as it resembles a Weber barbecue) by the crew and required five cameras to capture every angle. Explains Lantieri: “It’s a giant egg-shaped pod on the end of the stage that weighs 18,000 pounds. We knocked the legs out from underneath it and tumbled it down the stairs into the temple. It is always a challenge to be safe and get it to do what you want it to do, but it worked.”

By allowing debris to fall and shaking the cameras and sets with giant motors and concentric cams, the team simulated the quake with a combination of maneuvers. Continues Lantieri: “We built extra lighter-weight debris that we put on trips and releases so that we could drop them into the set on cue…as we moved the camera through. We took existing pieces of the set, split them and used hydraulics to split the 15-foot Sleestak head sculptures open.”

It was an intricate game of rigging to re-create the earthquake and tumble huge boulders across the set. Lantieri and his team took pieces of the set rock walls and cut them apart in giant pieces that measured 20 feet by 30 feet. They then attached motors and hinges to the pieces so that they would shake and loosen up. Much like the shifts that would occur in an actual earthquake, the parts moved out of sync.

The prop department joined the SFX department in creating items for Land of the Lost that weren’t par for the course of a typical film. At one point, the cast is slimed with Grumpy’s T. rex snot, which the SFX team designed from a coagulated methylcellulose. Ever the fringe scientist, Marshall even dowses himself with dinosaur urine that looks quite real but was actually green tea.

One of the key props for the film was the Tachyon Meter, Marshall’s homemade invention that enables his crew to transport to other dimensions. The prop department, helmed by SCOTT MAGINNIS, worked with production designer Welch and rendered a drawing that included flashing lights, see-through pumps and electronic readings. From a hodgepodge of objects, including an old iPod, they made by hand four identical versions of this measurement tool to be used throughout production.

Explains Welch: “The cumbersome strap-on Tachyon Meter is the kind of cobbled-together technology that you look at and think, `This guy is out of his mind.’ But at the same time, you think, `Maybe this actually works…’”

In addition to the Tachyon Meter, the props department souped up a vintage Toyota Land Cruiser for Marshall’s road adventures. The roof housed all manner of scientific gadgetry to allow him to stay mobile and prepare for anything that could possibly happen to a rogue scientist.

Deliverance to Cher: Music of the Film

When Brad Silberling was in preproduction on Land of the Lost, he ran into another longtime friend, composer Michael Giacchino. A frequent collaborator of J.J. Abrams, Giacchino has scored such memorable television shows as Alias and Lost for the director, as well as creating the signature sounds for Abrams’ filmic efforts, Mission: Impossible III and Star Trek. Just as well known for his work with Pixar, the composer also imagined the compositions for The Incredibles, Ratatouille and Up.

Much like Silberling, Giacchino was a big fan of the television series as a boy; he has fond memories of following Marshall, Will and Holly on their wild adventures every Saturday morning with his brother. As Silberling began to discuss the film with the composer, he knew he’d found the person he wanted to score it. “When we started talking, I realized Michael and I were on the same page with our musical ideas,” recalls Silberling. “We are both huge fans of Jerry Goldsmith’s work, especially the period of ’68 to ’71 where he managed to create unique and unusual textures for adventure…all the while keeping a bit of groove going. The Planet of the Apes series, in particular, was a great touchstone. Jerry brought musical elements to sci-fi that were unparalleled. We wanted to honor that discipline and loved the idea of composing each scene to elicit unexpected emotions from the audience.”

Perhaps the most curious musical choice in the franchise’s history is the origin of the opening sequence to the show. During the development, Sid & Marty Krofft selected the banjo as the instrument that guided us down the waterfall with our trio of explorers. Silberling recounts the story that Sid Krofft shared: “Sid told me that they got the idea to use the banjo after attending the premiere of Deliverance. They loved how those strings are so jarring and surreal and wanted to incorporate the sound into the show. Michael and I agreed we had to follow suit…and add in a bit of percussion.”

Composing for the film came with its share of challenges. To navigate, Silberling and Giacchino went with a singular rule: Don’t force laughs into a score, or it will equal comedy death. Explains the director: “Marshall, Will and Holly have made some dangerous choices to get to the Land of the Lost, but those come with a number of funny moments. With the score, Michael and I wanted to give the audience a smile-a wink and a nod with levity-but never hammer it home to say, `Pay attention! The music is forcing you to laugh now!’”

Silberling and Giacchino wouldn’t only look to soundtracks from their childhood for inspiration. Music from many decades courses through the film. Dr. Rick Marshall’s passion for musicals is evidenced by the uplifting “I Hope I Get It” from A Chorus Line, while The Andrews Sisters’ love letter to America’s doughboys can be heard when Chaka dances and mugs to the camera during a choreographed “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.”

No artist represents the ability to span time and space better than, well, Cher. While approaching the infamous pylon for the first time, Will-followed in due course by Marshall-is inspired by the pylon vibrations to jump into a makeshift rendition of the diva’s infectious pop anthem “Believe.” “A particularly proud moment for Danny McBride, I am sure,” laughs Silberling. “Watching him on the pylon singing Cher’s call to action…it just doesn’t get much more bizarre.”

Prêt-à-Portal: Costumes of Lost

The Land of the Lost collaboration continued with costume designer Mark Bridges working with Silberling and the cast to find their characters’ wardrobes. The khaki-clad Ferrell thought it would add to the comedy if, during the expedition, Marshall-because he’d forgotten his camping shoes-wore Florsheim zipper dress boots. Ferrell laughs: “I knew it was going to be hell on my feet and ankles, but I committed to it. So I wear the dress shoes the whole movie. Hopefully people will find it funny.

For the character of Holly, designer Bridges included a nod to the classic nostalgic plaid shirt and braids her namesake wore in the show, as well as the ’70s-style rust-colored pants. As the action revs up, however, so does Holly’s wardrobe. Her long pants get ripped into short shorts, and she wears a tank top.

“Holly was known for her plaid shirt, so we wanted to use the DNA of the original show and have a connection,” states Bridges. Finding the right plaid turned out to be a challenge. His team tried to match fabric from New York, L.A. and Europe but found nothing that worked. In the end, they created a custom plaid from scratch.

Friel was more than happy to don action wear. “What a change this has been from the fancy girl dresses I wore on Pushing Daisies,” she admits. “It has been great coming to work and pulling on shorts and a tank top and you are ready to go.”

Will has a costume that is a study in denim. Says Bridges: “Danny had seen an image of Chuck Norris in a film with the sleeves cut off a shirt and two tones of denim and said those clothes yelled Will Stanton.” With a few temporary tattoos-one of a naked woman whom McBride claims is his character’s mother-and a garish belt buckle depicting the Devil’s Canyon Mystery Cave logo, the actor transformed into Stanton and showed his character’s redneck roots.

The Pakuni women make a brief appearance in the film, and Bridges’ team had fun making their scanty bikini cloths-reminiscent of Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C. In keeping with the film’s theme, Bridges adorned the Pakuni women’s costumes with handmade jewelry from the Amazon, made of seeds and feathers fashioned together with gum resin. As was the rest of the cast and crew, Bridges was painstaking when it came to every detail in his corner of the film’s production.

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Land of the Lost

Starring: Will Ferrell, Danny McBride, Anna Friel, Jorma Taccone

Directed by: Brad Silberling

Screenplay by: Chris Henchy, Dennis McNicholas,

Release Date: June 5th, 2009

MPAA Rating: R for sadistic brutal violence including a rape and disturbing images, language, nudity and some drug use.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $49,438,370 (79.1%)

Foreign: $13,051,885 (20.9%)

Total: $62,490,255 (Worldwide)