That interest in exploring the heroism of individuals against overpowering forces and overwhelming odds has become a Tykwer trademark. “Salinger is not only fighting to uncover the bank’s crimes, but he’s fighting an ideological battle,” explains the director. “The executives run the world like a business rather than a place in which humans live and derive meaningful connection. They are pragmatists first and foremost, and Salinger wants nothing to do with their world view.”

When he first read the script, Tykwer’s interest was piqued by a key scene: the story’s hero, Louis Salinger, encounters the bank’s assassin by chance on a Manhattan street and an unpromising lead turns into a momentous shift in the case. The quiet tension of that scene, as Salinger and his colleagues follow the assassin, builds to a climax at the Guggenheim Museum. “That scene left an indelible impression and struck me as a great movie moment,” Tykwer recalls. “As the Guggenheim museum events unfolded immediately thereafter, I began to think this could become an interesting film. The last 40 pages of the script made it for me.”

“I think Tom is a real visionary,” Owen says of the director. “He has a fantastic sense of film style and a humanity that informs all his work. Perfume, Run, Lola, Run, Heaven, they’re all stylistically very interesting, modernist, and diverse, with strong characters. But, in addition, his sense of compassion and understanding of the human condition is an important dimension to his work.”

“Tom had a very specific vision for what he wanted,” says Roven. “But he’s also a great collaborator. He understands what everybody’s role is and he brings with him a great team that he’s been working with since the beginning of his filmmaking career. He’s one of the best people I’ve ever worked with in terms of not only how he sets up a movie but how he executes it. He gets amazing performances – he’s doesn’t just shoot the script, he enhances it with every scene.”

“He brought a level of excitement to every meeting starting from the first day I met him several years ago,” says producer Richard Suckle. “He has such tremendous energy and simply loves making movies. He’s a filmmaker with whom you really want to make the long journey movies require.”

Though a work of fiction, The International was inspired by the real life drama surrounding the downfall of the Bank of Credit and Commercial International. Founded in Karachi, Pakistan in the 1970s by Agha Hasan Abedi, the international bank quickly turned into the most pervasive money laundering operation in history. In addition to financial services, the bank ran a brisk sideline business in arms trafficking, turnkey mercenary armies, intelligence, and support of terrorism. Legislators in the UK and US finally unearthed these dealings in 1991 as the bank collapsed.

Eric Warren Singer, the screenwriter, says that the real-life BCCI scandal was “the largest criminal corporate enterprise in the history of the world. Over the past few years, culminating with the current financial crisis, we have seen an unprecedented escalation of corporate greed, but what fascinated me about BCCI was that it was more than simply greed; they were the bank for those who operate in the black and grey latitudes of this world – intelligence organizations, drug dealers, organized crime, and third world tyrants looting their own countries.

The BCCI was a full service bank that could provide its clients with a wide range of services. Whether it was moving your money anywhere in the world without a trace, having someone killed or anything in between, BCCI was the bank you could trust. And they were able to operate with impunity because just like terrorist organizations and organized crime, governments around the world – including our government – also needed and used their services.

Although the BCCI was shut down in the 90’s, there are banks that are engaged in the same type of business today – laundering money, promoting and fostering conflict in order to profit from the debt that it creates. The bank in our film is the 21st century version of BCCI and like its real world counterparts, is much more sophisticated and therefore destructive than its forbearer. The BCCIs of today have learned from the mistakes of the past and have created organizations whose structures are so complicated and Byzantine that it’s almost impossible for authorities to track and successfully prosecute them for their illegal activities.”

Though the BCCI provided inspiration, Singer says that by making a contemporary work of fiction the film could relate well to modern audiences at a time when he sees shades of the scandal in the news. “Although this film was rooted in events of the past, it was important to all of us that it be relevant to the present – and unfortunately, I don’t think anyone can dispute the striking parallels. At the time, the BCCI was the biggest Ponzi scheme ever, now only eclipsed by the Madoff scandal. The BCCI was one of the first international banks to aggressively pursue the practice of predatory lending,” he says, “and now the entire world financial system is experiencing its worst crisis since the Great Depression as a result of predatory lending and the unscrupulous manipulation of debt. The same lending principles used by credit card and mortgage companies to indebt individuals in the first world is utilized to enslave entire countries in the third world.”

In addition, says Tykwer, poetic license allowed the filmmakers some freedom in creating a thriller. “We didn’t want to hide the thriller behind a curtain of facts and elements to prove how closely related it is to actual events,” says the director. Adds Singer, “We were always aware that we wanted this film to have the engine of a quintessential 70’s thriller. We were trying to strike a balance between a film that was weighty enough to feel like an expose but had the velocity and visceral tension of a classic paranoid thriller.”

That The International called for an international shoot, filming in four countries, across two continents was irresistible for the filmmaking team. Producer Lloyd Phillips, a veteran of productions ranging from Beyond Borders to Twelve Monkeys, says, “Filmmaking, like so many other things, has become more global.

Studios are shooting in Russia for Russia, and in China for China, or in India for India. I love making movies in different parts of the world because the crews are getting better and better. Shooting in as many countries as we did on The International required careful planning, but the result is a huge amount of gratification.”

Casting the Film

Tom Tykwer and the producers had Clive Owen in mind for the role of Salinger from the very beginning, but it was seeing Owen’s praised performance in Children of Men that cemented the idea in the director’s mind. “When I saw Children of Men, I knew I’d found our leading man,” says Tykwer. “He was good-looking, but carried a world-weariness. He infused that character with a loneliness and roughness combined with a sensitivity that I also wanted to see in Salinger.”

“The contrast between Salinger’s values and those of the criminal network he opposes had to be clearly drawn,” says Tykwer. “Salinger struggles to stay within the limits of the law when the law seems like a useless weapon or an impediment to justice. So his tactics may sometimes exceed his authority but at the end of the day he is an agent of the law, operating on a razor’s edge between his conscience and his professional limitations. This struggle adds a realism and complexity to his character.”

Owen met with Tykwer over coffee during the film’s development. Together they shared a similar vision of the character and also found they were compatible colleagues. “Clive is extremely focused but very funny. Our meeting showed me what the production would be like. It was great. With him you can be extremely focused, but never lose the fun and joy of the work – a rare pleasure.”

“Salinger is a very unconventional lead character,” says Owen. “He’s not slick; he’s not the cool cop, tracking the bank down. He’s a volatile, passionate, committed, even hot-headed and obsessed Interpol agent, trying to make others see what he sees the bank doing.”

Equally resolute, but more level in her investigative approach, Eleanor Whitman watches Salinger’s back and keeps him in line when necessary. She leads the investigation and there’s a resilience and power to her character. “She is the balancing second protagonist in the film,” says the director. “Although there is friction between Salinger and Whitman, her energy and emotional power calms and steadies him and she gives him more clarity.”

Salinger and Whitman subscribe to the same value system and each chose to join the legal profession to effect positive change. But if Salinger walks the line between what is legal and what is not, Whitman is determined to prove that the good guys play by the rules.

“She’s not an icy career woman, but a real woman handling a chaotic life of family and career,” says Watts. “My character’s in control and has a lot of integrity. She’s operating in a man’s world so she’s on her game.”

Though she found the role intriguing, Watts was not eager to work so soon after giving birth to her first child. The director had to use all his powers of persuasion to lure her into accepting the role.

“I really had to talk her into it,” admits Tykwer. “Not because she didn’t want to do the movie, but because her baby was due just before our shoot. I had to convince her because I thought she was perfect for this character.”

The filmmakers arranged for Watts’ scenes to be backed up at the end of the schedule to allow the actress time at home. Joining the production in Berlin, two months after principal photography began, Watts adeptly juggled the needs of an infant with the rigorous demands of a movie. As a real-life example of a woman balancing career and family, Watts offered the director insight and first-hand knowledge into Whitman’s character.

The chemistry between Owen and Watts was palpable from the beginning. “It wasn’t surprising to me they were so immediately perfect. They’re a very easy and energetic match,” says Tykwer. “It was a perfect dream come true: Clive and Naomi, whom I consider two of the most interesting contemporary actors of their generation, working together for the first time in a film and both wanting to be involved in the development of the story and methodology of the characters. I felt quite blessed.”

“Clive is just brilliant,” says Watts. “He’s incredibly good-looking, but I’ve never seen less vanity in an actor. He’s a very un-moody, uncomplicated person and a lot of fun to be around and work with.”

Watts says she took the role not only for the chance to work with Owen and Tykwer, but because the project itself was so satisfying. “It’s smart and fast-paced, with a cross-section of locations and cultures and incredible production values,” she notes. “But what I really love about this film is that it feels very current and reflective of our times.”

At the head of the bank Salinger and Whitman so doggedly pursue is Jonas Skarssen, played by Danish actor Ulrich Thomsen. Skarssen has risen to the top of his game to run a vast banking organization with a few close associates. Impervious to the immorality of their actions, this elite group of financial wizards move money, people and governments around from the IBBC’s modern glass boardroom as though strategizing their next chess move.

“They’re not the super-enigmatic superstars of corporate bosses in previous eras,” says Tykwer. “They have slick appearances, but they’re rather normal, well educated rich neighbors one might encounter.”

Nonetheless, they are cunning and dangerous tacticians, coolly detached from the repercussions of his bank’s operations.

“His view is that he’s not creating the system, but the system created him and needs him,” producer Richard Suckle states. “To him, war and money are just business; he believes that if he doesn’t do it, someone else will.”

For Skarssen, it’s all a game – money creates debt, and debt creates influence. “He’s not out to rule the world,” describes the director. “He merely wants to spread his influence to see just how far it can go without being stopped.”

Wilhelm Wexler is from an older generation and a loner amongst Skarssen’s team of confidantes. A former Stazi agent from East Germany, he is more complicated than his colleagues at the bank and difficult to read. “He’s a ruthless killer, organizes assassinations, and, quite frankly, he’s a monster,” says Tykwer. “But at the same time, he’s the most fascinating monster in the film because there’s so much we like about him and sympathize with.”

Actor Armin Mueller-Stahl shrouds this character in mystery. “I think the secret, and one of the most important things in films, is not to open the door too early on a character,” the Oscar-nominated star (Shine) suggests. “A monster is deep inside and you can never tell if he’s a good guy or a bad guy.”

His character’s roots are all too familiar to the actor who lived in East Berlin for many years. A Renaissance man the world knows primarily through his films, Mueller-Stahl was once a concert pianist who also writes, paints, directs, sketches and draws.

The director believed Mueller-Stahl was one of his key castings because he brought a gravitas to the role, as someone in whom you inherently trust and believe. As with Skarssen, the director was not looking to depict Wexler as a one dimensional villain, but rather as a real person whom audiences could easily place in today’s world.

“It’s a film about our times. It’s about weapons, power, and money,” says Mueller-Stahl. “Perhaps we can’t make a better world by doing films, but we should always try.”

Brían F. O’Byrne rounds out the cast as the film’s mysterious assassin. Referred to only as The Consultant in the screenplay, he works alone, unnamed and physically unremarkable. O’Byrne struck a balance between inconspicuous and utterly unforgettable.

“Nothing is ever really given away about him,” explains O’Byrne. “You never see where he lives, for example, and he just exists in this netherworld. He’s like a shadow and a wonderfully proficient sniper.”

“We wanted this guy to be an invisible man who completely blends into his surroundings,” says Tykwer. “Someone you don’t notice, but who is still menacing and leaves a powerful impression behind. We stay curious about him, but we never understand who he is. He’s enigmatic throughout the movie.”

About the Production

To tell the story of The International, the filmmakers would need a team that was truly international, with expertise all over the globe. Joining the producing team with Charles Roven and Richard Suckle was producer Lloyd Phillips, who has vast expertise with a wide range of locations and logistically complex shoots. Phillips proved an invaluable asset as Suckle and Roven moved a globe-trotting production to Istanbul, Berlin, Lyon, Milan, and New York.

In addition, Tom Tykwer has worked with the same core group of creative collaborators for many years, and reassembled this team for The International. Among them are cinematographer Frank Griebe, who has shot every one of Tykwer’s films, production designer Uli Hanisch and editor Mathilde Bonnefoy. Academy Award-winning costume designer Ngila Dickson, based in New Zealand, was a new addition to the European foursome.

The film was shot principally on locations in and around Berlin and deliberately features the capital’s modern architecture rather than its other, more frayed, personality. The shoot out in the Guggenheim was filmed on a stage near Babelsberg Studios where the interior of the famed Frank Lloyd Wright-designed New York museum was painstakingly replicated. A week of exteriors in Istanbul began the production’s shooting schedule for the film’s finale; a day in Lyon established Louis Salinger at Interpol’s actual headquarters; three weeks of exterior scenes in Milan placed Salinger and Whitman in that city during the middle of their investigation. The final week of filming took place in New York where the filmmakers chose to reveal a more gritty side to the city, providing a contrast to Berlin.

Architecture features prominently in The International, through which old and new worlds are represented. An ultra modern landscape is the bank’s terrain in Berlin, where glass and concrete structures symbolize the contradiction between transparency and impenetrability of the financial world. Milan bridges old and new worlds by combining classical and modern architecture and an older, more tangible environment is depicted in New York. For the finale, Istanbul is a contrast between tradition and modernity in both physical and moral senses.

As Salinger closes in on his prey, the backdrop moves from highly-stylized modernism through to antiquated classicism.

“With Frank Griebe and Uli Hanisch, we developed a color concept as well to portray each individual city with a particular representation and, at the same time, make them all look combined as one world,” says Tykwer.

All the filmmakers shared a core belief that the thriller genre is one in which audiences are well versed and, as such, demands authenticity. “We felt it was important to shoot in all of these various locations to make it feel authentic, not in a showy way, but because it was organic to the story,” says producer Suckle.

Attempting to meet this demand, locations in all of these cities were selected that suited both the visual style of the film and made sense in the world’s real environment. Decisions were made to avoid cheating a street in Berlin for a street in New York, for example, so the film was shot principally at actual locations in all of these cities.

Cameras first rolled on The International in Istanbul, Turkey. The story’s climax unfolds in this mystical city amidst stunning silhouettes of minarets and domed mosques. Hot on the heels of his nemesis, Salinger’s frenetic pace takes him from the marbled courtyard of the Suleymaniye Mosque to the subterranean wonder of a Byzantine columned cistern; from dodging chaotic traffic in the city’s center, and weaving through the throngs of shoppers in the famed Grand Bazaar, to the relative quiet rooftops of Turkey’s largest covered market.

“Interestingly enough, we started filming where the story ends – with the finale of the movie,” explains Tykwer. “It was an amazing start. It was intense because we had so much to accomplish in just one week, but we were in one of the most spectacular locations I’ve ever filmed. I loved it, and hated to leave, but we covered substantial ground. It was very intense and interesting to start the movie with the final sequence, but we set the tone there.”

“I’ve produced some 25-30 movies over the years and this is the first time I’ve actually shot the end of the film first,” adds producer Charles Roven. “It’s challenging for the actors and, particularly, for the director to get the actors to that place where normally they’d have had months of being in the role to build upon.”

But it paid off and by the time the filmmakers, cast and crew packed up and moved back to Berlin for the bulk of shooting, The International was well underway in tone, pace and energy.

“We were very happy with what we saw in Istanbul because of the city’s unique stylistic mix,” production designer Uli Hanisch recalls. “It also straddles the border between Asia and Europe. It’s run down, but very active and busy at the same time.”

Hanisch and Tykwer have collaborated for years and share a creative understanding and shorthand in developing the look of a film.

“Tom gives you the space, freedom and independence to create what you want, but at the same time is very clear in his opinions about what he wants to see in his film,” says Hanisch. “It’s a balancing game of back and forth. We begin the process with conversation and, in this case, about how we involve the contemporary, modern and specific architectural places mentioned in the script.”

In the end, they came up with a helpful thumbnail sketch, or connecting visual thread throughout the film.

“All that is completely modern, almost virtual, is based more on the sinister side of the story and the old, shabby visual elements are related to the real world, representing good,” Hanisch explains. “This idea was a helpful way at the outset in which to get a line visually through the places we visit in the story.”

Thematically, Istanbul also fit with the script’s focus on business and trade. As Hanisch describes, “It’s a city run by business and everyone is dealing in something. There are shops and dealers all over and the greatest aspect about this was to have the final chase on the roof of the Grand Bazaar – historically one of the biggest bazaars. And, of course, completely interesting visually.”

The Grand Bazaar is almost a city in its own right. Massive and labyrinthine, it was once the largest covered market in the world, and retains the crown as the largest in Turkey today, crowding more than 58 streets with an estimated 4,000 shops with some 250,000 to 400,000 visitors daily. Carpets, pottery, copper and brassware, meerschaum pipes, jewelry and spices are just a sampling of what one can haggle over while sipping mint tea in one of the stalls. Tykwer filmed Clive Owen running through these stalls, gun in hand, amidst actual market-goers rather than hired extras. Needless to say, these people were somewhat bewildered at the guerrilla filmmaking tactics.

“It’s not a traditional structure such as you would find with a palace, building or church,” says Hanisch. “The Grand Bazaar is a confusing maze – a mass of corridors, completely chaotic and very expansive. And then, unusually, its rooftops have paths for reasons I don’t know. So when we first saw this, we thought what more could you want for a fabulous chase scene: existing winding paths on rooftops, set between two stunning mosques.”

Also irresistible was the opportunity to shoot beneath the city in a Byzantine cistern dating back to Constantinople of the Sixth Century. “We saw the cistern and thought: How can we possibly make use of this in the film? It’s just one of those irresistible locations. It’s a tourist attraction in reality, but in the movie we make it a secret cavern connected to the film’s mosque where two characters meet in private as though in a secret kingdom. To pretend the cistern is directly underneath our mosque is a bit crazy, but we couldn’t resist.”

Yerebatan Saray Sarnici, grandest of the hundreds of ancient reservoirs that still lie beneath the city, is often called the Basilica Cistern, or Sunken Palace, due to its size of 2.4 acres and 336 marble columns. Next to the Hagia Sofia on the Asian side of Istanbul (Anatolia), it has attracted thousands of tourists each year since its restoration in the 1980s.

“It was the last location to secure in Istanbul, and probably the most difficult,” says producer Lloyd Phillips. “Other films had shot there, but at night, and we needed it during the day when it had only ever been closed once for a half hour Presidential visit.”

The Suleymaniye (the Magnificent) is the film’s featured mosque. Built for a Sultan in the 16th century by a famous architect from the Ottoman period, the largest mosque of Istanbul with four minarets is spectacularly situated atop a hill overlooking the Bosphorus’ inlet and natural harbor, the Golden Horn. (In addition, another of the city’s famous mosques, the Blue Mosque, can be seen during the final chase across the rooftops of Istanbul.)

“I thought getting permission to film in the Suleymaniye Mosque would be the most difficult to lock of all the locations, but the Imans were wonderful supporters,” says Phillips. “They want to put Istanbul and Turkey on the map and our script didn’t represent anything objectionable, so they gave us access we never thought possible.

“Istanbul became a wonderful finale for the story. It’s one of the most fascinating cities in the world and also one of the most chaotic, but in this chaos brings something visceral and exciting which I think we captured. It was a great way to start our schedule. It was intense and it was crazy and I’d go back there to film in a shot.”

“Istanbul is one of the most rarely seen places in film history, particularly considering its diversity and beauty,” states Tykwer. “It’s also quite confusing at times because there’s such a mix of styles. I’m totally in love with the place. You could shoot an entire movie – several entire movies – there. I’m very happy to have Istanbul as the city in which to end the movie.”

Audiences are first introduced to Louis Salinger against the backdrop of Berlin’s newly built main train station. In fact, Berlin Hauptbanhof makes its film debut in The International. Tykwer wanted an iconic structure to open the film and immediately establish architecture as its subtext.

“This movie looks at the role of architecture in our lives and how much it influences emotional processes,” says the director.

“Expensive, modern architecture has changed the landscapes of so many big cities. It’s fascinating architecture, but seems driven by a desire to exude clarity with its lines yet at the same time is hard to read. I wanted to investigate this contradiction because it represents modern society and, particularly, the banking industry we wanted to describe in the film.”

Opened in 2006 after eight years of construction, this station is one of Europe’s largest and stands near to where the Berlin Wall once divided the capital. An impressive landmark structure with a massive glass roof, it’s prominently positioned near the parliament buildings of the Reichstag and Chancellery. At the station’s inauguration, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the transparency of the new central station was a symbol of a modern country open to the rest of the world.

Transparency is something to which the current corporate and financial world often lays claim. However, they are anything but as revealed in the film.

“There is an undercurrent to all these companies beyond the open book façade they present,” notes the director. “And I find modern architecture is like that too. It very often works with glass to show penetrability, yet also makes use of a lot of concrete – the most solid material one can hide behind. With the central station, for example, it appears see-through, but when inside you’re surprised to find many different levels with escalators everywhere. So, there’s a mystery and complication to this building you don’t see from the outside.”

The nearby government buildings of Berlin, straddling the Spree that runs through them, also made its cinematic debut. In the shadow of the Reichstag, these parliament buildings are predominantly glass and steel as well.

“I thought it was an amazing space to surround Salinger,” Tykwer explains. “It makes it seem as though they are trapped in this `brave new world’ environment and, as filmed at night, eerie. At the same time, however, there is a vastness to the area into which it appears one can escape. It creates a feeling of insecurity the film is attempting to illustrate – there is visibility, but you can’t read whether what’s coming toward you is friendly or dangerous.”

Berlin also played host to the film production’s largest set, as in an abandoned railway roundhouse in Berlin, the design team built two massive sets to house the Guggenheim shootout set.

Clearly it was not possible to shoot an explosive gun battle in the actual museum because of the damage it would cause. In addition, the Guggenheim’s rotating exhibits are constant and could never have allowed for the time needed for such a complicated scene. So finding a space large enough to recreate the museum’s rotunda then became the challenge. There was no such stage in Germany, so the roundhouse became the unlikely site. After weeks of searching far and wide, the production designer measured the ruin that sat outside his office window on a whim. Miraculously, it was a match.

Fans of Tom Tykwer, the Guggenheim board of trustees agreed to allow their museum to be duplicated and provided meticulous drawings from their vaults and a software program of the renderings. Bettina Lessnig translated these a year in advance of construction under the unique title of Guggenheim architectural supervisor for the film.

The Guggenheim set was a massive undertaking and took 16 weeks to build. Detailed plans and original sketches of Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece were painstakingly poured through by the art department with art director Sarah Horton and Uli Hanisch at the helm.

“Before we could even begin construction, we had to tile it’s roof, lay an asphalt floor over the top of the sand that was there, seal all the many holes, replace the broken window panes and transform the space into a makeshift stage,” recalls Hanisch.

Due to the extreme height of the Guggenheim, the sequence would have to be shot in two halves. “We had to cut it in half and first shoot levels three and a half to seven, tear it down and then build the ground level lobby to the third ramp,” Tykwer says. “We shot around the clock between main and second unit for four weeks on the first half, and two and a half weeks on the second. We ultimately spent six weeks of shooting there for a sequence that ended up being less than 15 minutes.”

The reconstruction of the museum was flawless and everyone who visited marvelled. Sarah Horton and construction manager Dierk Grahlow had conceived an elaborate scaffolding construction with a suspension system that cantilevered the ramps to gigantic anchors of concrete around the perimeter via an intricate system of cables.

“It’s one of the most amazing modern buildings in the world and very difficult to recreate because of its self-hanging terraces in a spiral shape,” explains Hanisch. “Out of pure respect and love for the building, we didn’t change a thing except to simplify our construction by leaving out the wings to the rotunda because we didn’t need them. It took sixteen years to design and build the real Guggenheim; we had sixteen weeks.”

“There were times when we thought we should rename the film, `The Guggenheim’, for the amount of energy, focus and planning that sequence required both with the actual museum and the set,” Tykwer laughs. “There isn’t a right angle in the entire building so every rounding and every corner had to be manufactured. This also offered a lot of problems later for our technical equipment while shooting.”

Finding the art to fill the Guggenheim set was another journey. Through the curator of the Hamburger Banhof, Tykwer was introduced to a local video artist.

“The driving energy of the film was to make it contemporary both in subject and vision and video art has developed in the last few years into a dominating art form,” says the director.

Video artist Julian Rosenfeldt jumped at the chance to be involved in Tykwer’s film and from his existing bank of work his video imagery was projected throughout the museum.

“It’s a virtual retrospective of my work with a lot of existing work along the ramps and a new piece developed for the film to hang in the center,” he explains. “I’ve called this new 15 panelled screen piece `The Opening,’ referring to the opening of an exhibit.”

In addition to the replicated museum set, the production also filmed in an actual museum, Berlin’s National Gallery. In another unprecedented gesture, the museum granted the production access to one of its rooms lined with priceless works of art. They even agreed to shift the position of paintings so characters Wexler and the Consultant could hold their clandestine meeting in front of the Arnold Böcklin painting, “The Crying at the Cross.” This Swiss symbolist painter from the 19th century also created another masterpiece showcased in the scene, “Island of the Dead.” The production was never allowed more than 30 people in the room at one time so as not to disturb the room’s temperature and potentially harm the paintings.

Wolfsburg is a young city, west of Berlin, planned by the Nazis for workers of the Volkswagen factories. With the opening of Autostadt in 2000, Volkswagen’s auto delivery center and theme park, and The Phaeno Science Center in 2005, the otherwise sleepy town is visited by millions of tourists and architectural enthusiasts each year.

These landmark architectural sites set the scene for the film’s IBBC and Calvini business headquarters respectively. The film crew spent a brief two days filming these exteriors in Wolfsburg, but months of planning by Lloyd Phillips were involved to secure these days.

Production designer Hanisch visited Wolfsburg in pre-production and in these two sites found extraordinary modern architecture.

“Autostadt is such an unusual place. It plays with a virtual, modern surrounding we found fascinating,” Hanisch notes. “The huge interior of the KonzernWelt building and its front exterior were fantastic in themselves, but then in relation to the theme park behind – it was almost supernatural. The choice to use this location was very much about the image or feeling we wanted to sell of the IBBC.”

Autostadt is a landscaped theme park owned by the Volkswagen Group where customers pick up newly-purchased VWs and tour the seven individual pavilions of each of the manufacturer’s brands. Linked by an underground computer-controlled conveyor tunnel to the distribution center, the site’s Car Towers are impressive transparent glass spheres measuring 157 feet high and hold 400 cars fresh-off the assembly line.

Never before opened to a film crew, Autostadt’s CEO Dr Otto Wachs granted Tykwer permission to film in the building where its magnificent opening glass panels, the largest of their kind in the world, were featured.

“In the film we play with the idea of translucence in big business,” says Hanisch. “A bank like the IBBC is anything but with its highly covert criminal activities, but they pretend to be this kind of open-minded, consumer-friendly, world-friendly business. Glass can be transparent or it can be a reflection and we play with that in the film thematically and visually with the camera.”

Next to Wolfsburg’s main train station, and across the Mittelland Canal from Austostadt, sits London-based conceptual architect Zaha Hadid’s otherworldly design, The Phaeno Science Center. The museum is the largest interactive science museum in Germany with cutting-edge exhibits and commissioned artwork. Hadid’s innovative building was conceived as an “adventure landscape, a futuristic venue for the journey of discovery”. An astounding concrete structure, the unusual award-winning design has been described as a “hypnotic work of architecture – the kind of building that utterly transforms our vision of the future.” The museum serves as the film’s location for the Calvini family’s business headquarters.

In late November, at the onset of winter, the production bid farewell to Berlin and made their way to one of Italy’s largest cities. Calling Le Méridien Gallia home, the crew settled in to the hotel on the Piazza Duca D’Aosta for its three weeks of filming. Opened in 1932, the Gallia’s façade is a splendid example of art nouveau and its grand lobby, rooftop and back entrance served as key locations for the film.

Whitman and Salinger’s investigation brings them to Milan in search of incriminating clues they believe an Italian businessman vying for political office can provide.

Next to the hotel, and dominating the same large square, is the city’s imposing central train station, Stazione Centrale di Milano. Under Mussolini, the station’s original design became more grandiose when the dictator wanted it to represent the strength of the fascist regime. When the station was inaugurated in 1931, its size was record-breaking at more than 650 feet wide and 236 feet high. Without a defining style, it’s a kinetic blend of many including Liberty and Art Deco.

However, competing for prominence in the Piazza Duca D’Aosta is the Pirelli Building. Designed by Gio Ponti in 1950, the elegantly styled skyscraper is Milan’s tallest structure at a height of 417 feet. Currently housing the Region of Lombardy’s offices, the looming modernist structure is juxtaposed against the classical neighboring architecture, a visual thematic thread throughout the film.

“Milan works as the transitional zone between Berlin and New York because both old and new worlds are represented in the locations,” explains Tykwer.

The production’s arrival in the city was a novelty. Unaccustomed to a major film production in their city, Milan warmly embraced the cast and crew and provided much needed logistical support.

With permission from the Mayor of Milan, Letizia Moratti, the film’s political rally with 800 extras was staged in the Piazza with multiple cameras and one flying overhead in a helicopter. The Governor of the Region of Lombardia, Roberto Formigoni, allowed filming to take place on the top floor of the Pirelli Tower, 31 stories up, to set the film’s political headquarters for Umberto Calvini, played by Italian actor Luca Barbareschi.

Despite never seeing these locations first hand, writer Eric Singer’s descriptions in the script were incisive.

“It felt like he had been to Milan for a tremendous amount of time because his attention to detail was unbelievable,” says producer Suckle. “His research was meticulous. And we got lucky in that everything he wrote worked practically for filming. These locations were chosen by Eric because they’re not only in close proximity to each other but they all tied together narratively.”

With only one week in New York, the cast and crew worked at break-neck speed to complete the daunting schedule of exteriors.

“Going to New York was the opposite of Berlin. I was very familiar with the city, but through movies,” Tykwer admits. “Unlike Berlin, I wanted to show the city in a nearly nostalgic way, one that is reminiscent of a culture that is vanishing in other places in the world.”

One of the primary goals while in New York was to capture the actual Guggenheim, both inside and out. And there was only one day for each.

Attracting many paparazzi and onlookers on a Sunday afternoon, Clive Owen as Salinger entered the museum and exited bloodied for the beginning and end of the sequence. The exterior of the museum during this time was hidden behind scaffolding for a long-planned restoration project, and removed by visual effects in the film’s post-production.

“This is the 50th anniversary of the Guggenheim and they’ve spent tens of millions of dollars restoring the landmark,” Phillips recalls. “The staff enjoyed the humor in allowing a film to come in and portray the destruction of the museum.”

With only one day to capture all of the sweeping wide shots required to complete the work already filmed on set in Berlin, the cast and crew spent nearly 16 hours inside the Guggenheim. Moving a massive crane in and out of the museum’s lobby, shuffling hundreds of extras and steadily moving from one ramp to the next, Tykwer and his team accomplished an enormous feat.

Other New York days were spent in Brooklyn establishing Whitman’s residence, in Central Park with a blood-drenched Salinger, and on the streets of Manhattan spotting the Consultant and then trailing him to the Guggenheim.

“This sequence through New York City was inspired by The French Connection,” says Tykwer. “This film had such a big impact on me and one of the films Eric, Chuck, Richard and I always referenced when we first started talking about The International.”

Production notes provided by Columbia Pictures.

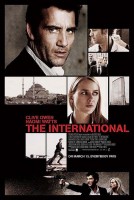

The International

Starring: Clive Owen, Naomi Watts, Brían F. O’Byrne, Ulrich Thomsen, Armin Mueller-Stahl

Directed by: Tom Tykwer

Screenplay by: Eric Singer

Release Date: February 20, 2009

MPAA Rating: R for some sequences of violence, language.

Studio: Columbia Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $25,450,527 (49.1%)

Foreign: $26,391,327 (50.9%)

Total: $51,841,854 (Worldwide)