Dr. Parnassus has been gambling with the devil, Mr. Nick for centuries. He made a deal with the devil when he met his one true love, giving his daughter to Mr. Nick when she reached her 16th birthday. Now Mr. Nick is coming to take her. Dr. Parnassus must fight to save his daughter.

Blessed with the extraordinary gift of guiding the imaginations of others, Doctor Parnassus (Christopher Plummer) is cursed with a dark secret. An inveterate gambler, thousands of years ago he made a bet with the devil, Mr. Nick (Tom Waits), in which he won immortality. Centuries later, on meeting his one true love, Dr. Parnassus made another deal with the devil, trading his immortality for youth, on condition that when his daughter reached her 16th birthday, she would become the property of Mr Nick.

Valentina (Lily Cole) is now rapidly approaching this `coming of age’ milestone and Dr. Parnassus is desperate to protect her from her impending fate. Mr. Nick arrives to collect but, always keen to make a bet, renegotiates the wager. Now the winner of Valentina will be determined by whoever seduces the first five souls. In this captivating, explosive and wonderfully imaginative race against time, Dr. Parnassus must fight to save his daughter in a never-ending landscape of surreal obstacles – and undo the mistakes of his past once and for all!

Production Information

The announcement of a new Terry Gilliam film tends to evoke a lively mixture of excitement, curiosity and not a little apprehension. The visionary director has the reputation of a singularly creative maverick, but his creations’ passage to the screen has not always been easy. The tragic loss of Heath Ledger during the production of THE IMAGINARIUM OF DOCTOR PARNASSUS, threatened closedown, but Gilliam fought to reconfigure the story without losing the fine performance which his star had already committed to film. The director, his ensemble cast and his crew worked tirelessly together to complete the journey which had begun in the fervid, boundless imagination of Gilliam and his co-writer Charles McKeown less than eighteen months before.

“Since the format of the story allows for the preservation of his entire performance, at no point will Heath’s work be modified or altered through the use of digital technology,” the film’s producers reassured the media and public: “Each of the parts played by Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell and Jude Law is representative of the many aspects of the character that Heath was playing.”

“I am grateful to Johnny, Colin and Jude for coming on board and to everyone else who has made it possible for us to finish the film,” added director Terry Gilliam, “and I am delighted that Heath’s brilliant performance can be shared with the world.”

In the modern-day fantasy adventure, Dr. Parnassus (Christopher Plummer) has the extraordinary gift of inspiring the imaginations of others. Helped by his traveling theatre troupe, including his sarcastic and cynical sidekick Percy (Verne Troyer) and versatile young player Anton (recent BAFTA-winner Andrew Garfield), Parnassus offers audience members the chance to transcend mundane reality by passing through a magical mirror into a fantastic universe of limitless imagination.

However, Parnassus’ magic comes at a price. For centuries he’s been gambling with the devil, Mr. Nick (Tom Waits) who is coming to collect his prize – Parnassus’ precious daughter, Valentina (Lily Cole) on her upcoming 16th birthday.

Oblivious to her rapidly approaching fate, Valentina falls for Tony (Heath Ledger), a charming outsider with motives of his own. In order to save his daughter and redeem himself, Parnassus makes one final bet with Mr. Nick, which sends Tony (played during his several visits to the world beyond the mirror by Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell and Jude Law) and Valentina and the entire theatre troupe on a ride of twists and turns, in and out of London and the Imaginarium’s spectacular landscape.

The film began principal photography at the beginning of December 2007 in Britain’s capital, where Gilliam shot dramatic scenes featuring Parnassus, his company and their imposing horse-drawn dwelling cum theatre, against a wide range of the city’s familiar landmarks. The wagon, driven by Verne Troyer’s Percy, became a familiar if mindboggling sight for the City of London’s merry pre-Christmas revellers as it clattered through the nighttime streets.

A series of wintry night shoots saw the Imaginarium’s travelling stage fully dressed and unfolded in a bustling fairground dominated by the familiar profile of Tower Bridge; then at the centre of a drunken riot in the imposing shadow of Southwark Cathedral; and later invaded by Russian mobsters in the glorious Victorian confines of Leadenhall Market. Two of the principal characters were suspended perilously, in an icy gale and an artificial downpour, from Blackfriars Bridge over the Thames, while the gigantic, crumbling magnificence of Battersea Power Station, the largest brick-built structure in Europe, hosted a variety of domestic scenes featuring Doctor Parnassus and his extended `family’.

On completion of these present-day sequences, the production moved to Bridge Studios near Vancouver in Canada for seven weeks of blue-screen photography, creating the epic grandeur of the Imaginarium. Vancouver also offered some striking locations, such as its magnificent art deco theatre, The Orpheum, which hosted the film’s charity ball and press conference

Background Notes

In November 2006, Terry Gilliam and Charles McKeown started on the script, the third of their written collaborations, following “Brazil” and “The Adventures of Baron Munchausen.”

Gilliam had decided to write something original again, after a number of projects based on finished scripts or adapted from books. “It was nice to see whether we could still do it ourselves from scratch,” he explains. He set himself to exploring his store of unused materials – various ideas, some from unmade films, which had been lying around in a drawer – and started dragging to see what could be used.

He wanted to explore the idea of a troupe of travelling theatre people, based in modern-day London, who entered into a variety of exotic and fantastical worlds. Gilliam also devised the central character of a man who is a bit lost, out of his time, and out of gear with his audience, who don’t want to listen to the stories that he tells any more, while it was McKeown who came up with the name Parnassus. “It’s his adventure, really, I suppose. It wasn’t absolutely fixed, but that was fairly clear in Terry’s mind. I think the idea of Dr Parnassus as a semi-Eastern medicine man just evolved. I don’t think he started quite like that.”

The next stage involved them sitting down and throwing ideas around, although as Gilliam admits, there was no real plan to it. McKeown felt that choice was very important in their movie – entering this extraordinary world involves a series of choices which rule the lives of the characters. The two writers worked on computers, e-mailing back and forth. “Then we’d have another sit down,” says Gilliam. “We’d go through it and, little by little, something was worked out. There is no form as such, it was just sitting down and hammering away at this big block of marble until something beautiful was carved from it.”

“We talked for a couple of weeks around the subject, very broadly,” says McKeown. “We spent a day talking about the whole range of subjects and then, finally, we started talking about the thing itself, and how it related to current events. It was a mixture of a whole medley of stuff for a couple of weeks and then we started to write a treatment.

“In fact, I insisted that Terry write the treatment because he had a better grip of what it was he wanted than I did at that stage. I didn’t really quite get it at that point, I don’t think. Although it was fun and I could see the story, I thought that Terry had a clearer view. Then I started writing scenes and dialogue and characters and settings and so on, clarifying it a bit. I would send him by e-mail six or seven pages, and he would work on that. He’d change it and embellish it and take what he wanted and add what he wanted, and so on. Meanwhile, I’d send him another lot of pages and he would send that back and show me what he’d done.

“It was a rolling process, going back and forth and, at one point, we’d stop when we got right to the end of the script, and discuss where we were going, and where we were so far.”

According to Gilliam, “It was like a tennis match, throwing things back and forth, and slowly things kept developing. You have ideas, you start plugging them in – and out of it comes a tale. It’s nice working with Charles again – it’s been a long time since `Munchausen’.”

“I don’t think what we ended up with was what we started out with, in every respect,” admits McKeown. “Maybe Doctor Parnassus is fairly close to how he started, but the other characters changed a bit as we went along. Certainly, the character of Valentina, Parnassus’s daughter, changed a lot and the other characters shifted too, when they weren’t quite working as well as they might do.

“We break the rules really. You are supposed to focus on a central character. That’s one of the recipes for success, to have a central character with whom the audience can identify. But this is a group piece and although it’s called Doctor Parnassus, and he’s very much the centre of it, and everything goes on around him, nevertheless, you are caught up in everybody else’s story as well.

“The theme of imagination is central – the importance of imagination to how you live and how you think and so on – and that’s very much a Terry theme. For some time, he’s taken other scripts and books and made them his own, in the sense that they are identifiably Terry Gilliam movies. But I think this goes further than what he’s done more recently. He’s had more of an input, this is more his thing. This is more a Terry Gilliam film than there has been for some time.

Terry always throws himself into what he does with such tremendous energy and vigour, that it has to be worth his while. It has to be worth knocking himself out for, and I think `Brazil’ was like that, and to some extent `Munchausen’. It has this visceral quality, and Terry doesn’t hold back when he commits himself. This is something to which he has committed himself 120%, and it has all the possibilities of delivering more of him than the other work he has been doing recently.”

“I’m not sure whose autobiography it is,” confesses Gilliam. “I mean, I thought it was vaguely related to mine, but I’m not sure any more! It’s about the struggle of creative people… artists… They try to inspire others, encourage them to open their eyes, to appreciate the truth of the world, but most are not successful – that’s the reality.

“It’s a tragical/magical idea – a group of extraordinary people in an amazing theatre, travelling round London, but nobody’s paying attention to them. I am convinced that in the modern world people don’t see what is really important any more. Everybody’s trapped in their IPods or their video games or playing the stock market – all interesting and time-consuming – but there are really extraordinary and important things happening out there and nobody is paying attention.”

Putting It on Film

“I did storyboards for the first time in a long time on this one,” remembers Terry Gilliam, gleefully. “That’s why I was enjoying it. It was like going back to my earlier films on which I storyboarded everything myself. That’s really an exciting part of the process as you write a script – sitting down and starting to draw pictures. It’s transformed. It becomes a different thing. I don’t read the script again, we rewrite it based on what I’ve just drawn and that’s really nice. We build models, we use CG and mix everything up and try to get everybody confused, so you can’t quite see how we’re creating our world. It’s like a magic trick…….

Amy Gilliam was taking her first steps as a producer, working in Vancouver alongside Oscar-winner William Vince, when she heard that her father was writing a new script. “Having worked in the film industry for twelve years and having made my way up the ladder, one of the biggest wishes of my career was one day to produce a film with my father,” she remembers. “When I read his script, it was all those things that I’d been brought up with – imagination and adventure – everything about it is just magical. It’s not a specific story that I’ve known from my childhood, but I think many elements of it are close to my heart and my experiences. Terry was running around trying to raise the finance and I thought to myself `I want to make this. It would be an amazing thing to achieve’. Bill Vince saw the excitement and energy and passion in me for this project and he was the sort of man who, if he believed in something and in someone, he wanted to make it happen for them.”

Samuel Hadida joined Bill and Amy as a producer, having distributed Gilliam’s “The Brothers Grimm” in France. He was already impressed with the script, but was then delighted to be presented with the art book that Terry produced to illustrate his vision: “It helped us to visualise and to get the sense of what he wanted to achieve. It is a very visual movie, with a lot of special effects involved, and it was great that everybody was on the same page. This world was being created in storyboard and there we saw a preview of where he wanted the animation and the look of the film to go – and that was a big challenge.”

“The design of The Imaginarium probably began with Pollock’s toy theatres in London,” remembers Gilliam. “When I first came here there was a shop that still exists today. They make these Victorian toy theatres, which are cardboard cut-outs, and they have always intrigued me. I went down to the Museum of Childhood, because I knew they had several old original ones there and I photographed several and fiddled with them in Photoshop.

“For the designs on the outside of the Imaginarium, we had books on arcana, hermetic symbols, Robert Fludd. I’ve always loved that stuff. I don’t know what half of them mean, but they trigger ideas and so we started gathering them together and applying them to the theatre. There are snakes, devils, evil eyes, pentagrams. All sorts of things – probably a mixture of every kind of arcane symbolism ever invented. Medieval imagery and iconography is so good and healthy for your imagination. Alchemists were trying to describe the world, trying to describe the cosmos, trying to make a visual, philosophic sense of it all. It’s unlike modern reality and it always seems to stick in my mind more than our current view of reality does.”

“Now that we have finished shooting, I know what the film is about, better than when Charles and I were writing it. I often feel I make a film in order to find out what it is I’m making! We knew we had these two warring factions – the guy who might be the Devil and the guy who might be God, but they’re neither, they are below that, they are Demiurges. And we shifted what each is offering the world. Parnassus is offering you the chance to expand your imagination, but that doesn’t mean it is going to be easy or a pleasant ride. And we always made the choices Parnassus offers mean – if you should choose the right one – that you might achieve some form of enlightenment, but it will always be a really difficult path. The easier road is invariably with Mr Nick. During the writing we kept changing what Mr Nick was selling. In the final version, he sells the idea of fear, of insecurity. He plays on weakness, whereas Parnassus plays on the fact that certain people are strong and willing to take chances.

“Tony says of Parnassus, `if he’s got this power to control people’s minds, why doesn’t he rule the world?’ Anton answers with a line I’ve always liked: `He doesn’t want to rule the world – he wants the world to rule itself’. Take responsibility. It’s important to plant ideas like that.”

Casting

“Christopher Plummer was the first one we cast, I think,” explains Gilliam. “He’s a great actor. He’s theatrical, he’s of a certain age, and he has been a huge star. His daughter Amanda Plummer worked in `The Fisher King’ with me and there’s an interesting relationship with him and his real daughter. What’s fantastic about Christopher is that his theatrical sense proved to be absolutely perfect for the character – and the fact that he wanted to find the humour in the character all the time.”

“I seem to be playing the title character in the movie,” muses Plummer. “Not the Imaginarium itself, but Doctor Parnassus. Terry Gilliam called me out of the blue and said `I’d like you to play my title creature – it’s a wonderful old man.’ I thought he probably called because there are very few old men left who are actors who can actually speak – and I’m one of them. I get luckier every year, because they get fewer and fewer and, as long as I’m still kicking and alive, I can report for duty. And so I said yes.

“I don’t know what I did with Parnassus. He tended every now and then to be very melodramatically written, so, seeing how colourful and busy the sets were and all the other creatures in the film were moving around a great deal, because Terry likes movement, I decided to try to play Parnassus rather still and introspective, rather than outwardly melodramatic. I think it works, because he has an inner sorrow – the fact that he’s betrayed his daughter with the devil. I think that that balances him – it isn’t just all silly fantasy. There has to be some sort of dark and tragic side to this movie that can be dealt with in a light way, but nevertheless it’s there.”

Gilliam continues: “A Dutch animator was trying to get in touch with Tom Waits (whom I consider to be America’s greatest musical poet) and asked me if I’d send Tom a script of his, which I did. It was the first contact I’d had with Tom in several years. He turned down my friend, but asked `have you got anything going for me?’ And I said `well, there is this interesting part in my new film….’ and that was it. I said I’d got a part and he said `I’m in’. Before he’d read the script.”

“I play the devil,” explains Waits. “I don’t play a devil or somebody who’s kind of evil. I play the devil. It’s kind of a curious conundrum – how do you play the devil? How do you play an archetype that large, that deep in history? I finally realised that I was just going to have to play it myself – it’s my devil. It’s the way I play the devil. So I hope I’ve been doing what Terry expected. I hope I’ve been exceeding his expectations. I’m not always sure that I am, but I hope I am.”

“When we were looking for our Valentina, Irene Lamb, who was casting the film, said `you’ve got to see Lily Cole’,” remembers Gilliam. “So we did a little screen test and bingo, it was done! I just wanted somebody who was extraordinary looking to begin with, and I wanted somebody who was able to look sixteen. The reality is that when we began shooting with Lily, I thought I might have made a mistake, because she was so inexperienced and was surrounded by such great actors. But she rose to the occasion and just got better and better. The end result is an absolutely wonderful performance.”

“It feels like a lot of hard work,” admitted Cole on location. “But it’s really rewarding and Terry’s got a really good heart. All the people that are involved have a really good heart, so there’s always been a very positive atmosphere to work in and very collaborative. It doesn’t feel as though there are any egos fighting. There’s no hierarchy, as Terry will joke – even though there is. There’s that attitude which encourages everyone to give their input, which really is an amazing, special thing.

“It feels very, very different from modelling, but I expected it to feel different. The practicalities are obviously very different and the industries feel very different. In the scheme of the world, I’m sure they are quite similar, but side by side, there are a lot of differences. I feel much more pressure and much more involved acting, which for me, anyway, is a great thing. I feel it’s therefore much more rewarding – I always feel quite stunted when I’m just modelling. There is very little you can actually bring of yourself to it, whereas acting is partly aesthetic, of course, which is why you get the job, but there are twenty million places you can go from there. It’s: `OK, what can you do? Come on and prove it’, which makes it much harder, but, by the same standard, much more exciting.”

“Verne Troyer was cast very early on,” says Gilliam. “He was briefly in `Fear and Loathing’ – for two seconds. I thought if we’re going to have a troupe of extraordinary people, an ordinary small guy is not good enough – we’ve got to get the smallest guy out there. But, it’s not just his size…. the thing about Verne is that I know his attitude and he’s absolutely spoton for Percy, because Percy’s cynical, he’s a smart-ass, he just doesn’t take it from anybody, and Verne is like that.”

Troyer agrees: “There’s definitely a lot of me in him. He’s kind of a hardass. He’s sarcastic, cynical, doesn’t really give two s**ts about anything. I love playing this character. If I could play him again I would. I like a challenge. I don’t find Terry too demanding, because when you’re doing a scene and you want to get the full effect, you don’t want to just lollygag around. So I enjoy Terry when he’s directing. He knows what he wants and he has a lot of great ideas and it just makes it fun.”

According to Gilliam: “Heath Ledger was here in England working on `The Dark Knight’ and he had brought over a mutual friend, who had done the storyboards for `Brothers Grimm’. They were doing an animated musical video and they needed a place to work. I offered them space at Peerless (our VFX company) in the projection / boardroom. One day, I was in there to show my storyboards to the people who were doing some pre-visualisation work and Heath and Daniele were sitting there. I start the show and begin explaining the sequences and, while this is going on, Heath slips me a little note which says `can I play Tony?’ He had seen the script, but I had never asked him to be involved. `Are you serious?’ I said. He said `Yes, because I want to see this movie’. It was as simple as that. Once Heath was on board, I thought things would be easy, that the money would come pouring in…….wrong again!

“Finally, people were telling me about Andrew Garfield. I’d never seen him, but he sent an audition tape that he and his girlfriend had made in Los Angeles. He played each scene three different ways and I thought `the guy’s absolutely, stunningly brilliant’. Within a week I got a call from Heath saying, `have you cast a guy named Andrew?’ I said `yeah’. He said, `you won’t believe it, I’m on my way to his birthday party.’ Strange forces were at work already.”

Garfield was thrilled to be cast: “Anton’s very joyous, very open-hearted, very warm and childish, but I feel he has more wisdom than most people who are twice his age. He’s got a very good way of seeing the world, it’s very pure, very innocent. I think Terry sees things very black and white in his life. He likes to compartmentalise things into being good and evil, within his films and within his life and within the world. So I think I fall into the good bracket, although I show signs of darkness taking over me. But I think I’m Terry as a kid, Terry as a young man, who’s trying to figure out who he is and where he fits in and trying desperately to be good and trying desperately to help in any way.

“Terry’s very, very honest. He doesn’t bulls**t you into thinking that he knows any better than you do. He treats you as an equal and he expects you to produce something on the day, so it’s not all left up to him and his team around him. There’s a real pressure every day, coming into work, to be in the moment, to be inventive, to be brave. Actually, he really encourages crossing over a line that you wouldn’t normally cross. You know when he’s happy, and you know when he’s not quite happy. But he’s never didactic, he’s always encouraging.”

The next stage of Gilliam’s collaborative journey had begun. “Rehearsals were interesting, because the actors were trying to find their characters, but the clearest was always Christopher. We would begin a scene as scripted, as we had written it, and then I’d say `Parnassus now comes down the stairs’ and Christopher would say `I don’t think so, I don’t think that Parnassus should enter at this point’. And I’d say `why?’ and Chris would reply: `well, he will just be standing around with nothing to do….’ A great theatre actor always knows how to and when not to make an entrance.

“I have allowed more ad-libbing on this film than on anything I have ever done and it started because of Heath…..he was just so full of ideas and fresh dialogue and so unbelievably fast and inventive. He was still, in some sense, speeding from playing The Joker, which had liberated him in a way that he had never experienced before. He was always telling me `I am doing things in scenes that I didn’t know was inside me. I cannot believe it.’ During the first couple of weeks of rehearsal, Andrew, who, before this, had never really ad-libbed, tried to compete with him, but Heath, in character as Tony, was too fast and focussed and intimidating. It didn’t work. Eventually Andrew found he could compete on a different level and protect his character’s vulnerability at the same time….by becoming playful and light. It gave Anton a kind of power that Tony couldn’t quite deal with.

“I was feeling my way into the film more than I normally do. A lot of it was due to Heath’s enthusiasm and energy and the new ideas that were pouring out of him. I was watching and thinking `let’s use them’. I always say I’m not the director, I’m just the filter. I don’t care whose idea it is, as long as it’s the best one. Fortunately, I’m the guy who gets to choose which one is the best.

“Interestingly, when Heath died, Andrew managed to fill part of the vacuum Heath left – his ad-libbing had become brilliant and very funny. He said he hadn’t realised he could do comedy before, having played very intense, serious characters. It was amazing to watch things shifting and growing, as if the film was making itself.”

The producers are delighted with the ensemble cast. “The most important thing is when the actor plays the part, and gives it life,” says Samuel Hadida. “It is great to have effects and design and visuals, but emotion is only given to the film by the performances. And this is where the director needs a very special skill; to find the best actors for the world he has created. Terry sees the spark inside their eyes, the way they move, the way they deliver and the way they act. I think that he has an incredible talent. He not only has a world of his own, but he also knows how best this world can live.

“As a producer, you have to provide all the tools and all of the freedom for a director like Terry Gilliam to be able to express himself – to make it possible for his vision to progress from paper to the screen. Our goal is to help him achieve his vision from the moment of its creation, to give him everything he needs to make the best movie possible.”

The Worlds of Doctor Parnassus

Gilliam’s close collaborator, cinematographer Nicola Pecorini, was involved from the beginning of the project. “It’s the level of poetry that is present in the script that appealed to me the most. Having shared Terry’s last ten years of passions and frustrations, I totally understand where `Parnassus’ comes from. A tired man, who has been trying to enlighten his fellow humans, to teach them to let their imagination fly and flourish, to consider the power of dreams as a richness and not as a burden. Parnassus is Terry. The script is the fortunate child of years of battle against the system, of frustrations accumulated trying to give shape to sublime ideas.

“I read the story as a fantastic sum of Terry’s entire artistic career: you can find in it all the elements that were present, in one way or another, in a veiled or blatant manner, in all his previous works. It’s definitely a very mature script and I firmly believe that all those out there (and luckily there are a lot of them) that love and appreciate Terry’s previous works will find that `Parnassus’ is the apotheosis of Gilliam’s art.

“We tried to plan every single detail in advance. The Imaginarium sequences, especially, are broken down shot by shot, frame by frame. But even the most careful planning cannot avoid the unexpected, nor human failures, in delivering what’s needed in a timely and precise manner. Terry and I share a common vision of the `cinematic stage’, namely a 360-degree approach to framing. We reached a total symbiosis. Without talking, we always reach the same conclusions and adopt the same solutions. I find it very easy to work with Terry, even if technically it’s very difficult. Lighting for a 360-degree field of view is certainly more complicated than sticking to long lenses. The major difficulty is to have other people understanding our approach.

“It is true that he uses wide-angle lenses, but the reality is that the world is made of wide angles. The human vision is wide-angle, so the reality is that you want to offer choices to the spectator and that’s Terry’s approach. With wide-angle you have the choice of what to look at and you must use your brain to look at things. When you start going tight and have little depth of field you are deciding for the audience what they get to look at. Terry doesn’t have that approach in filmmaking and I’m totally with him.

“Every day you learn something new. The moment I finish learning I will change my job. Hopefully that will never come. If you don’t learn something new, you must change jobs, because it means you know how to do it.”

Mick Audsley, Terry’s film editor on “Twelve Monkeys”, a decade previously, has been waiting for the opportunity to work with the director again. Like Nicola, he also gets involved at a very early stage. “First of all, I start by taking on board the screenplay. I do quite a lot of work early on, because I can perhaps see issues which I’m concerned about, before the film is shot. In conjunction with the director, I have a big say, but I don’t have a final say in what ends up on the screen, so my goal is to piece together what I see as the route of the story and orchestrate that story for the audience – a bit like a conductor for an orchestra. So what we do in putting the film together, and the way in which we pace it, is crucial to the audience’s journey as they sit and watch it. Notions of speed and comprehension, and performance and selection of performance are all wrapped up in that.

“I think the particular challenges in this film are in the blue screen world, or the artificial world that we’re creating behind the mirror. The material, when I receive it, is only partially realised, in fact it’s only one fragment of the information that’s required. So we have to start the process and make editorial decisions with the pieces that come in, even though a lot of the visual information isn’t there. So that’s quite challenging.

“Of course, the main thing is always whether the performances are working and then, secondly, that the construction of those particular scenes allows the digital work and the digital information to be told in the right order. But I’ve only got a vague understanding of it – Terry’s probably got it all in his head and so it’s a liaison with him and with the visual effects team to present it as coherently as possible.”

Costume designer Monique Prudhomme is also delighted by her close collaboration with the director. “Terry is open to everything that is interesting, everything that catches his fancy, and he is very generous in his approach. If you have an idea he will always listen. He is really interested in the process – there’s nothing that is set. If you get into that flowy mode and you stay fluid then you go with it. It’s an adventure. “You start with what I call hunting and gathering. You have ideas of what would be good. You start in books and looking at images. Terry also has his favourite images that he wants to bring in and from there you hunt and gather. You gather clothes, and you gather pieces – hats and coats and scarves – and suddenly, when the actor comes, you create the character by moulding it, it’s like a sculpture.

“I always see my job as being a facilitator for the actors to find their characters. So, by being open to a process, instead of thinking that the actor is a coat hanger, you create a character with the stature, and the body, and the expressions. Then you mould it and invent things. This film has really enhanced that process.

“I think that costumes are there to support the character, or really to create the image that will be remembered of the character. So the actor has to feel comfortable with that image. For Doctor Parnassus, for example, who is an immortal man, I figured he would always be cold living in London, always wet, always humid because they live in these derelict areas. So I dressed him in layers, undershirts, and shirts and sweaters and linings and then coats on top, and scarves. So that layered look could be used for actions – taking things off, putting things on – but also to create this character who is grumpy and wants to get on with life. “It is a privilege and an honour to work with Terry. He has so many ideas. His world is so eclectic and it really connects to my sensibility as well. If I have two ideas, he has twenty. To work with him is to exchange ideas and interest. As long as I can keep him interested and we can keep fluid, the fluidity means that, if one day we have an idea and the next day a better one, we always go for the better idea. So it’s in constant flux, which is a fabulous way of working.”

Hair and makeup designer Sarah Monzani found the two different worlds in which the film is set to be an interesting challenge for her and her team. “I’ve known Terry for a long time. I absolutely know the way he works. He’s very hands on and whatever he’s written, it’s all inside his head. The biggest task is to drag it out of there. He’s very generous because he allows you to get inside, and drag a bit out at a time, because it’s not possible with something like this to take it all in at once. You read the script and that’s one thing… and then you read it again and something else appears and it goes like that all the time.

“We have two main stories here. One is the people involved in the film, the players if you like, or the people in Doctor Parnassus’ life as we see it. They’re normal people who are basically grubby and live in a kind of grungy world – they’ve got hardly any water in their wagon. And then you go into this magical world of these little, mini-performances on stage and each show has a different look, which is mostly marked by Valentina. Because Doctor P is obviously thousands of years old, he’s able to bring to each stage performance something he’s learnt from his previous years, so anything from mediaeval times to the modern day.

“All the different looks I created for Valentina are based on that: either things she would want to do as a young girl, or things that she found in the dressing up box that Doctor Parnassus had from years ago. I imagined all the costumes as having come out of an old dressing up box that Monique Prudhomme has presented me with. I’ve developed the characters’ looks from what she’s given me. So it’s a madness. It’s a complete madness!”

Keeping the madness under control is Terry’s daughter, producer Amy Gilliam. “I feel as though I am responsible for everything and I’m a control freak and I’m very protective of the project and especially the director because he is my father. This is my second film as producer and the first one that I am properly and deeply involved in. It’s a UK / Canada co-production and very complex for me, a steep learning curve.

“It’s incredible that it all came together so quickly. There was something very special when I read the script. The parallel between Dr Parnassus and my father, which a number of people have suggested, is very real to me as his eldest daughter. That is what intrigued me – that was the beginning of a long and sometimes painful commitment for me.

“Being able to do it with my dad – there’s just no-one better – has been a great experience. Everyone tells me that it was probably one of the hardest films I could have done, with all of the ups and downs and nightmares and dramas that we’ve been through, so to have achieved it and come through with something that’s so magical and spectacular, that we are all so proud of being involved in – all the heartache, blood, sweat and tears – has been extraordinary and enjoyable.

“I love working with my father, I wouldn’t do it otherwise. Maybe the worst thing is making a difference and drawing a line between work and family life. There are times when I have to say `No’ as he tries to talk over a family meal about issues with work. `That’s tomorrow, send me an e-mail’ and he runs straight away to his study and sends me an e-mail!”

She pays fond tribute to her Oscar-nominated Canadian fellow producer William Vince who lost his battle with cancer shortly after the film wrapped in Vancouver. “It was amazing to be a co-producer with Bill and to find someone who wanted to make this dream come true. To have someone who supported and believed in me, to have someone to work with and learn from, that was amazing. I miss him very much.”

Carrying On

On January 22nd, 2008, during a stopover in New York, as the production transferred from London to Vancouver, Heath Ledger died of an accidental overdose of prescription drugs.

A devastated Terry Gilliam’s immediate decision was to close down. “I just said I don’t know how I’m going to make this thing work. I was too distraught to actually work out what to do. But everybody around me said `no, no, you have to carry on, you have got to do it.’ Everyone was throwing in encouragement and ideas. The magical mirror solution was obvious, as we had already covered most of the scenes with Heath that happen on this side of the mirror, but the big question was `do we get one person to take over the part or not?’ I already felt it couldn’t be just one, it was too much of a weight, so we should get several people to do it if we could. I actually rewrote fairly quickly. There were only a few days to come up with a convincing solution and, luckily, there was no shortage of ideas, good and bad.

“We didn’t have to rewrite that much, it was more or less a matter of juggling and trying to rearrange scenes that Heath was planned to be in, to see if we could make them with a double or find some cinematic trick.

Losing Heath created a situation that demanded clever solutions which pushed me into doing all sorts of things that were not my original intention. For example, we altered the part of Martin the drunk, at the beginning of the film, so that he was played by two actors. This established the principle that people can change on the other side of the mirror. Then I just started calling my friends and a lot of people who were very close to Heath.

“And so the three heroes, Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell and Jude Law came to Vancouver to play these various aspects of Tony, the character which Heath Ledger began. Their willingness to help rescue the film and Heath’s last performance was an incredible act of generosity and love. A beautiful and rare moment in our industry and, as a result of their involvement, the film is even more special: it’s more surprising; it’s become funnier. All in all, it’s a bit more magical.

“We had to make a major leap to solve the problems created by Heath’s untimely death, but, thanks to Parnassus and his Imaginarium, we have a magical mirror where, when we enter, things can be different, things are enhanced, are more extraordinary, are more wondrous. And so we made the leap. Every time Tony, Heath’s character goes through the mirror, he becomes a different aspect of himself, played by different actors. It’s been a constant delight to see what Colin, Johnny and Jude have brought to the part. Tony is an even more complex character and I think the audience will be on more of a rollercoaster ride as a result.

“We had to throw our schedule into the air. The shoot became a circus act of juggling, quick changes and contortions. There was a great deal of ad hoc movie-making, reorganizing the schedule as we shot, trying to fit everybody in. To make it even more stressful, Bill Vince was very ill with cancer. But, somehow it worked. Everyone was incredibly brave and positive, managing to jump into the spirit of a very desperate situation. And then, suddenly, we had finished the shoot. I don’t know how, but we did it. This is a different film than the one we began. It’s strange, but the forced solutions may have focussed us into creating a better film. The constant pressure on all of us was to end up with a film that was worthy of Heath’s last performance.”

For Amy Gilliam, once they had decided to complete the movie, it was a hectic scramble to keep the momentum going: “While Terry was in London, figuring out the script changes, I spent three weeks running around Los Angeles. Everyone wanted to see the project completed, for many reasons – for Heath, for Terry, for everyone that was a part of it. The crew didn’t want to leave, they didn’t want to give up, because they were in love with what they were doing and so proud of what they were a part of. And I am very, very, very proud of the film and of everyone that’s been a part of it, because without everyone’s enthusiasm and motivation it wouldn’t have been made.”

Fellow producer Samuel Hadida shares her pride in the dedication of all concerned. “They knew that this movie was important for everybody. From the blessing of the actors who joined us, to the commitment of the crew and of the production – for the ensemble of people working on this movie, it’s not just a movie, everyone was committed to making it happen. We were right to take the decision to continue, because Terry has created something that is unique and I think that it’s going to be a blessing for people that worked on it.”

“Heath seemed to be with us the whole way,” notes Gilliam. “His energy, his brilliance, his ideas… the tragedy of his death and the creative decisions which that forced us into making,,, are the reasons that this is truly a film from Heath Ledger and friends.”

Production notes provided by Sony Pictures Classics.

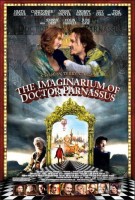

The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus

Starring: Heath Ledger, Christopher Plummer, Tom Waits, Lily Cole, Andrew Garfield, Verne Troyer, Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, Jude Law

Directed by: Terry Gilliam

Screenplay by: Terry Gilliam, Charles McKeown

Release Date: December 25, 2009

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for violent images, some sensuality, language and smoking.

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $6,083,141 (14.9%)

Foreign: $34,668,682 (85.1%)

Total: $40,751,823 (Worldwide)