True Fiction: The Script

The Hurt Locker, winner of the 2008 Venice Film Festival SIGNIS Grand Prize, is a riveting, suspenseful portrait of the courage under fire of the military’s unrecognized heroes: the technicians of a bomb squad who volunteer to challenge the odds and save lives in one of the world’s most dangerous places. Three members of the Army’s elite Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) squad battle insurgents and each other as they search for and disarm a wave of roadside bombs on the streets of Baghdad-in order to try and make the city a safer place for Iraqis and Americans alike.

Their mission is clear-protect and save-but it’s anything but easy, as the margin of error when defusing a war-zone bomb is zero. This thrilling and heart-pounding look at the effects of combat and danger on the human psyche is based on the first-hand observations of journalist and screenwriter Mark Boal, who was embedded with a special bomb unit in Iraq. These men spoke of explosions as putting you in “the hurt locker.”

In 2004, journalist and screenwriter Mark Boal spent several weeks embedded with a U.S. Army bomb squad operating in one of the most dangerous sections of Baghdad, following its movements and getting inside the heads of the men whose skills rival those of surgeons-except in their case one false move means they lose their own life rather than the life of a patient. His first-hand observations of their days and nights disarming bombs became the inspiration for The Hurt Locker and, eventually, a script that simultaneously strips down the classic American war epic and broadens its concerns to encompass themes as universal as the price of heroism and the limits of bravery in 21st century combat.

“It [the experience in Iraq] made a deep impression on me. When I got home, I thought ‘people have no idea how these guys live and what they’re up against,’ and then later I started thinking about it dramatically and doing a fictional story about men who voluntarily work with bombs,” says Boal, who also created the story for the drama In the Valley of Elah, for which Tommy Lee Jones received an Academy Award nomination. “On a character level, I was intrigued by the sort of mental and psychological framework that a bomb technician develops on the job. What kind of personality is comfortable with extreme risk and with living so close to death? And in a thematic sense, the bomb squad seemed like a promising entry-point for a war movie.”

Coalition bomb squads have played a pivotal but mostly underreported part in the war, and bringing their work to light was also part of Boal’s motivation for writing the script. The Army relies on its bomb squads as the first -and last-line of defense against the IEDs that have become the insurgency’s weapon of choice. The opening scene in the movie depicts the kind of situation that US soldiers in Baghdad encountered on a daily basis-sometimes 10 or 20 times a day, according to Boal. “Someone finds an IED, they call in the bomb squad and the bomb squad has to deal with it while everyone else in the military pulls back.”

“What many people don’t know is that although Baghdad was horrifically dangerous in those years, it could have been a lot worse,” he adds. “On any given day, for every bomb that exploded in the city, there were probably ten or fifteen that didn’t detonate because of a few, secretive bomb squads that were in theater.”

In order to capture the tension of Boal’s intricately detailed, nuts-and-bolts descriptions of bomb disarmaments, it would clearly take a filmmaker with her own gift for innovative storytelling to bring all the nuance on the page to life with visceral, poetic imagery and powerful performances.

When it came to evoking the hair-raising intensity of bomb squad work, there was no better choice than Kathryn Bigelow, who began her career as an artist, working with the avant guard conceptual art group Art & Language in New York, before becoming one of cinema’s leading filmmakers and a director renowned for stylistic innovations, masterful suspense, and ground-breaking action sequences. Bigelow’s cult following and reputation as one of the most inventive filmmakers in world cinema began with her vampire noir Near Dark and was cemented by her influential surfer-heist classic Point Break, the science-fiction thriller Strange Days, and the cold-war submarine drama, K-19: The Widowmaker.

With The Hurt Locker, Bigelow marries Boal’s screenwriting style – closely-observed characters, and realistic, intense set pieces -with her own unique vision; the result is incredibly suspenseful and action-packed cinema that reinvents the war movie for the post-Vietnam era.

Bigelow had met Boal while she was developing a television series from an article he had written in 2002. They stayed in touch, and Boal contacted the filmmaker when he returned from Iraq. “Obviously, Kathryn is a brilliant director who has a terrific feel for how physical and psychological danger effect character, and so I was pretty much fell out of my chair when she said she was interested.”

“I’d been a fan of Mark’s reporting for some time,” Bigelow says. And Boal’s observations of the bomb squad seemed like a perfect fit to a filmmaker known for films that put key characters in extreme situations. “The fact that these men live in mortal danger every day make their lives inherently tense, iconic and cinematic,” she adds, “and on a metaphorical level, they seemed to suggest both the heroism and the futility of the war.”

Bigelow and Boal decided to produce an independent movie that would be character-driven, suspenseful and “intensely experiential,” as Bigelow puts it, by placing audiences on the ground with the bomb squad. “Everything about this movie-the directing, script, camera work, music, editing-was conceived from the beginning with the single goal of creating that heightened sense of realism that underscores the tension, without losing the layering of these complicated characters.” says Bigelow.

With Bigelow’s guidance, Boal worked on the script on spec for the director, writing in what he calls a “naturalistic style, a sort of true fiction,” that seeks to replicate the tension and unpredictability of war itself, and mirror the daily grind of real life bomb squad soldiers who disarm bombs week after week, year after year.

They wanted The Hurt Locker to avoid polemics and instead place the audience in the soldiers’ point of view in order to give them a vividly authentic sense of what it was like to walk the high-wire act of a bomb technician. “The dialogue is meant to feel life-like and spontaneous, as if it wasn’t written, while at the same time revealing intimate character detail and capturing the excitement of their work,” he says. “The portrayals of bomb disposal and urban warfare are pretty faithful to real life incidents that soldiers have faced in Iraq and Afghanistan, although the characters themselves are composites.”

He worked on 17 drafts with Bigelow before finding a final version, and the pair continued to tweak the script during filming so that the major set-pieces could be sculpted to fit the available geography of the shooting locations. In the end, the result was The Hurt Locker, in which Boal pays tribute to the spirit and dedication of the soldiers in Iraq with his layered story-telling and sharply delineated, intensely human characters.

Once the script was completed, Bigelow called in favors from her years in the business. “We said to people, the bad news is we have no money, no studio, and no means of outside support,” Bigelow recalls. “But that was also the good news, because we had creative freedom and we could work outside the box.”

Bigelow and Boal approached financier Nicolas Chartier, who raised funds for the production through his independent company, Voltage Pictures. “It was the best script I’d read since Crash,” says Chartier, who had helped sell that Academy Award winning film. “And I had wanted to work with Kathryn for a long time. She has an incredible eye for action and is top directors in the world.”

The Hurt Locker caused a sensation when it screened at the Venice Film Festival, receiving a ten-minute standing ovation, and earning four awards, including the SIGNIS and Human Rights Film award, as well as a nomination for the Golden Lion, the festival’s highest honor. It was praised for being a film that “avoids dry ideology,” according to the La Navicella VenenziaLa Navicella Venenzia, “in a controlled but complex style.” “An uncompromising approach to the Iraq war and its consequences seen through the experience of the bomb diffusion specialists for whom war is an addiction rather than a cause,” stated the SIGNIS committee, “Kathryn Bigelow challenges the audiences view of war in general and the current war in particular [by] demonstrating the struggle between violence to the body and psychological alienation.”

Shortly after Venice, the film screened to widespread critical acclaim at the Toronto International Film festival, winning The Screen Jury competition for the best reviewed film of the festival, based on an international slate of newspaper and magazine critics. Shortly thereafter, Summit Entertainment purchased the domestic distribution rights to The Hurt Locker, insuring that the film would reach audiences in America.

In the Kill Zone: Characters and Cast

At the heart of The Hurt Locker are its characters – men who risk their lives daily in one of the most dangerous places on earth – fighting the odds to stop bombs from detonating in a city overrun with IEDs and insurgent snipers. Against this deadly backdrop, Sergeant James becomes the heart of the story – a mercurial, swaggering, expert bomb technician with a cheerfully anarchical approach to combat and, paradoxically, a masterfully controlled skill-set, who shocks his new team members with his enthusiastic disregard for established procedures.

Despite his teammate’s vocal misgivings, James refuses to modify his mood or change his behavior, representing the kind of all American hubris and spirited independence that can spark great sacrifice – and also dangerously misfire.

“James really anchors the movie, he’s the galvanizing center of the team in that he instills both fear and admiration, ” says Kathryn Bigelow. “a lot of what happens in terms of character development is about how the other guys react to this almost elemental force that comes whirling into their already on-edge lives.”

When it came to casting the film’s three leads, Bigelow wanted to find breakout, young actors in order to heighten the film’s authenticity and boost its surprise factor-avoiding the calming familiarity of an established movie star. “There’s a convention that the movie star doesn’t die until the end of a film, and I think that in our case having that certainty would undermine the naturally suspenseful, unpredictable quality of being in a war where death can happen anytime, to anyone,” explains Bigelow. “With The Hurt Locker, I wanted it to be as tense and real as possible, and that mean having actors who were relatively fresh faces so the audience wouldn’t know who among the three main characters was going to live or die by virtue of their public profile.”

In considering who might play Staff Sergeant James, Bigelow conducted an exhaustive search of up and coming young talent before finding an actor with the range to realize the role of the wild, alluring, good ‘old boy with a surprisingly rich interior life. The search ended when Jeremy Renner came to her attention via his turn playing the notorious title character in the film Dahmer. “Jeremy gave an incredibly nuanced performance in that movie, eliciting compassion and revulsion in almost equal measure,” says Bigelow. “I found it an arresting display of major talent, and from that moment forward was determined to work with him.”

“It takes an incredibly skillful and intelligent actor to embody James’ bravado and allure in a nuanced way that doesn’t seem artificial, and Jeremy is as skillful as an actor gets,” Bigelow adds.

“The role calls for the ability to command authority while also seeming to be totally reckless,” she continues, “that’s a very difficult but seductive combination which Jeremy can inhabit with seemingly natural ease.”

James is the catalyst for much of the film’s conflict. “His solitary focus is on the bomb,” says Boal. “That’s where he gets his engagement and his sense of being alive. He’s most at home when he’s working on a bomb and most out of place when he’s just with other people. So in a sense, the price of his heroism is his isolation, or loneliness. It’s a recipe for disaster to have these three men working together in the same unit.”

Jeremy Renner, who grew up in rural California, identified with the character’s salt-of-the-earth background, and he was also drawn to a universal quality in the script that transcends its immediate setting. “What attracted me was that it’s not simply about the Iraq war,” he says. “It could be about bull riders instead of EOD. It’s a backdrop for these three guys and how they approach life.”

The actor sees some similarities between his hotshot character and himself. “James’ philosophies are a big part of me. He’s a man of few words and a lot of action. I’m not a big talker. I’d much rather get something done.”

Like many people, Renner was unaware of the existence of the Army’s EOD squads until he read the script. “I could never do what they do. Just the thought of laying there next to a 155 [artillery round] and my heart starts pounding. They’ve got to have a switch in their head that they can turn on and off.”

Casting the role of Sergeant J.T. Sanborn-the proud, affable, level-headed intelligence specialist who has the toughness to go toe-to-toe with James-posed it’s own special challenges, recalls Bigelow. “Sanborn needed to be James’ equal in terms of being a strong presence, and he has to adhere to protocol in a way that seems thoughtful rather than rote,” the director explains. “It was a very difficult part to cast because we needed someone who projected real solidity and reliability while at the same time having the capacity for great sensitivity, which as it turns out it is not that common.”

Anthony Mackie caught Bigelow’s eye during his performances in She’s Gotta Have It, We Are Marshall, Million Dollar Baby, and especially in his role as a menacing drug dealer in Half Nelson opposite Ryan Gosling. “He completely controlled the screen in a relatively small part,” she remembers. “You couldn’t take your eyes off him. Anthony has that cunning magnetism that has true star quality.”

For his part, Mackie was attracted to the depth he saw in Sanborn’s character, which allowed him to find many levels on which to play. “Sanborn hides behind his machismo,” says Mackie. “There has to be a kind of superhero aspect to these soldiers. If they wake up every day in fear that every minute is the last, they’ll drive themselves crazy. Down deep though, he’s very humble.” In contrast to James’ consuming passion for his work, Sergeant J.T. Sanborn is the film’s Everyman. “He spent seven years in intelligence before joining EOD,” says Boal. “He’s a smart, capable, reliable, charismatic guy who has never encountered a whirlwind like James before. There’s an alpha male component to his personality that runs up pretty hard against James, who’s also an alpha male but of a much different stripe, so you have these two versions of masculinity dueling each other as they fight in these really tricky circumstances in Baghdad.”

Providing the third side of the film’s inter-personal triangle is Specialist Owen Eldridge, the youthful, junior member of the team who is in search of a mentor, and who tries but ultimately fails to find solace in either Sanborn’s stoicism or in James’ indifference to danger. As the pain of the war creeps up on the young soldier, darkening his innocence, “Eldridge has to be every mother’s son,” explains Bigelow, “there’s a frankness, and earnestness to him that allows him to wear his fear on his sleeve.”

Bigelow had been impressed with Brian Geraghty’s performances in Jarhead, We Are Marshall, and Bobby before she cast him as Eldridge in this film. “Brian exhibited the fierce and the vulnerable in perfect measure,” she says. “He’s natural, totally fluid.”

Of the three men, Eldridge is the youngest in both age and his experience in the military. “He’s triangulated between Sanborn and James,” says Boal. “He’s looking to see which of these two older, more experienced men holds the answer to how to survive. He’s willing to throw his lot in with either, and he flip-flops back and forth, and eventually becomes seduced by James’ decisiveness – and then he comes to regret that choice.

By the end, he’s disenchanted with James for very good reason, but there is a point in the movie when Eldridge feels that James’ way is the way to go and that he needs to just ‘man up’ and follow James’ example.”

“I feel like he’s the emotional heart of the film,” Geraghty says. “I think Eldridge is over it and he’s just trying to get by and get home. Sanborn and James are more lifers and army guys. Eldridge reacts completely different under gunfire than they do.”

“I have three tremendously strong actors at the core of the piece,” adds Bigelow. “I felt they would meld together into a seamless ensemble, as well as retain their strength individually.” Bigelow has earned a reputation for casting newcomers ever since her first film, The Loveless, in which she gave Willem Dafoe his first screen credit, and then later in Point Break, when she cast Keanu Reeves as a rugged FBI agent at a time when the young actor was known for stoner comedy.

With the three leads in place, the next role to cast was Sergeant Matt Thompson, the square-jawed, team leader beloved by his teammates, who opens the movie. “We needed an actor who could immediately convey the ease of command and warmth with his men that good sergeants possess,” explains Bigelow. The directors first choice was Guy Pearce: one of the most widely admired actors of his generation for his performances in L.A. Confidential, Momento, and The Proposition.

“Having Guy open the film sets up a sense of credible reality from the very start,” says Bigelow. “You need that because the world is so exotic, but Guy just seems like he belongs in it.”

“I’ve wanted to work with Kathryn for years,” says Pearce. “And ultimately the material has to be the reason why I go and do any film. This film is packed with action, but it’s about people and emotions. It’s about people trying to connect with each other. The way in which the script was written is really fascinating and Mark and Kathryn have both done a beautiful job of capturing and realizing these characters.”

Director Bigelow’s reputation for making exhilarating, original films and eliciting strong performances from her actors attracted some big Hollywood guns who were willing to take on some of the film’s more intriguing cameo roles, including David Morse, Ralph Fiennes and Evangeline Lilly.

Morse was electrified by the script’s picture of a world that is completely unpredictable and dangerous. “It doesn’t care who you are,” he says. “Anybody can go at any time. There’s a surreal quality to it. I think that says what the experience in Iraq is about.”

A Realist Eye: The Production

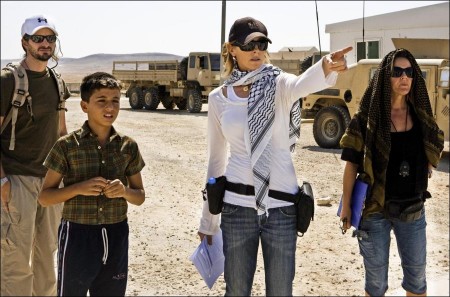

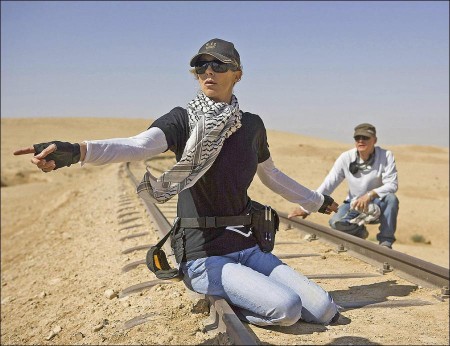

Director Kathryn Bigelow is renowned for pushing the filmmaking experience to its limits in order to create vivid, arresting images and powerfully emotional stories. For The Hurt Locker, she took her cast and crew into the Jordanian desert to work under some of the most rigorous conditions possible. With director of photography Barry Ackroyd, she devised an unconventional and remarkably effective technique for filming that simulates the spontaneous feeling of a documentary, while immersing viewers in the nonstop tension of its characters’ world.

“Barry is a master of evoking the ‘you are there’ immediacy that the story demanded,” says Bigelow. “At the same time, he’s one tough Englishman who put up with ridiculously long hours in the Middle East, in summer-not to mention sand storms and food poisoning.”

Since his early days in documentary filmmaking, Ackroyd has refined his in-the-moment style in award-winning feature films including United 93. “Making a feature film is not a documentary and it’s not docudrama,” he says. “The essence is not to think about it too much, but to try to be surprised in the way that a documentary would surprise you. Yes, we can set things up and we can redo it, but it’s still possible to be surprised when the performance happens.”

Bigelow made the choice to film The Hurt Locker with four handheld cameras simultaneously. She has shot with multiple cameras on each of her films, using as many as 12 at a time. “When I storyboard the entire film, every scene is broken down to its essential elements,” she says. “I look at the boards shot by shot. It’s at this point that I realize what the technical needs of the shoot are. I can determine the camera needs, as well as the blocking of each scene. Even before we’ve chosen locations, I have basically ‘shot’ the entire film in my head.”

To meet the ambitious schedule of shooting The Hurt Locker’s many extended action sequences in only 44 days, the crew worked six-day weeks and blitzed through complicated, highly choreographed blocking that Bigelow would outline in her head well in advance. “I look at each sequence like a three-dimensional puzzle that has to be translated to a two-dimensional surface,” she says.

It all starts with the script, she says. “In this case, it was the logic of bomb disarmament. Early on, I realized geography would be central to the audience’s understanding of what the bomb squad does on a daily basis. Military protocol for a bomb disarm in the field is approximately a 300meter containment. That’s a big set.”

On The Hurt Locker, the filmmakers used multiple points of view and constantly moving cameras to create the kind of immediacy that places the viewer in the center of the fog of war. “We were always asking ourselves, “‘What can you do with the camera that can make you feel like you’re a participant?'” says Ackroyd. “How do you put yourself in the middle of the scene or put yourself right on the edge of the scene and participate in what goes on? You can give the actors the space to do long takes with continuous action. The art department gave us big sets for the explosions. People were doing their stunts as big long takes and the camera was just participating in it. You don’t ever stop; you just keep going with it. Kathryn gave us the space to do that. She said go ahead and keep shooting, keep shooting, keep shooting, We would be waiting for ‘cut’ sometimes and it wouldn’t be coming, so we knew the shot was working well.”

At times, the set seemed as chaotic as the film’s Baghdad setting. “With four units covering a particular scene, an actor might not realize that a camera was suddenly 40 degrees off his left shoulder,” says Bigelow. “The crew sometimes didn’t know where the actor was going to go. It created this tremendous situation that heightened the realism and the authenticity.”

“We had cameras everywhere,” says Renner. “We called them Ninja cameras, just hiding all over the place. We never knew where anything was. Barry was out there himself running around. It was absolutely amazing seeing him run as fast as we did, carrying his camera down these dirty alleys full of syringes and kids throwing rocks and he always had a big smile on his face. That inspired me.”

Shooting in this way required flexibility on the part of the actors. “There was only so much you could prepare for,” says Geraghty. “But if you’ve done your homework and you know your character, all that stuff falls into place and you can just put your trust in it. There are so many technical things outside of your performance. Lights, camera, heat, camels, goats-you have to just keep going.”

Ackroyd also used the camerawork to punctuate the often frenzied activity with moments of quiet. “Kathryn encouraged the cameras to be active,” he says. “I was always thinking about the moments of stillness that you have as well and how those things go together. If those things come together in the right way, motion is one dimension, and silence and lack of motion add another element. If you get those things right, the whole film will have balance.”

In order to simulate the troubled landscape of war-torn Baghdad, Bigelow decided to film in Jordan, which borders Iraq to the west. Some of the locations were just a few hours drive from the combat areas. “It adds a certain x-factor that just permeates every aspect of the performance and the production to be that close,” says Bigelow, “and it becomes part of your reference points if you actually spend time off set within an Arabic culture.”

The production took place in and around the poorer neighborhoods in the city of Amman, which had architecture similar to Baghdad’s. The climate and geography of the two countries are also comparable, with the added bonus of the presence of ethnic Iraqis who could fill small parts and work as background and bit players, further heightening the realism of the film.

“There are about one million Iraqi refugees living in Jordan who have fled the war, and as it turns out among them is a pretty big pool of professional actors, and it was great to be able to cast them – it was good for the movie, and it was good for the set,” explains Bigelow.

“I remember speaking to the two men who play Iraqi POWs in the desert sequence-and asking them what they did in Iraq. They said, we were prisoners of the Americans. I thought maybe there was a problem with the translation because they played prisoners in the movie. Then I realized that no, they actually were prisoners in Iraq, and now they are playing prisoners. It was surreal, and a little uncomfortable, but then they laughed and said they were happy to have the work-but I thought ‘maybe we are taking this authenticity thing a little too far.”

Nevertheless, the desire for authenticity extended to the actor’s living arrangements as well. In order to instill the military’s close camaraderie, Bigelow housed all the actors on set in a basic communal tent with a dirt floor, rather than in air-conditioned trailers. “You could meet them for a coffee on the weekends, and they’d still be in character,” recalls Boal. “They’d be in a café talking military jargon to the waiter, “we need three cappuccinos by oh-six-hundred. Roger that.”

Before the shoot, Renner, Geraghty and the other principals spent time learning from Army EOD teams at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin. Located near Barstow, California, the NTC is the army’s premier training camp. Its Mojave Desert location makes it perfect for instructing troops headed for the Middle East. “It’s just crazy,” says Geraghty. “When there’s a bomb, most people want get as far away from it as possible. These guys are trained to do the opposite. Their job is to go in as close as they can get.”

But what cast and filmmakers remember most about shooting in Jordan was the summer heat. “There was something incredibly immediate about shooting in an environment that was unforgivably hot and putting the actors in a very arduous situation on a day to day basis,” says Bigelow. “Just sand, wind, sand, heat, sun and sand.”

Not surprisingly, the actors found the conditions challenging. “It would be 130, 135 degrees,” says Mackie. “It was so hot you could feel your brain cooking in your head. Everything was magnified by the level of body armor we had to wear.”

Renner adds: “Working in Jordan was extremely difficult in the sense that conditions were very hard. But it made my job as an actor easier. That sweat is real sweat. Those tears are real tears of pain, so I’m glad we weren’t on some soundstage. I feel like I got just a sliver of an idea of what an EOD or anybody in the military might go through every day. It’s unbelievable how tortuous it can be.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve had to do physically as an actor,” he continues. “I love to be challenged and I was really, really challenged on this. I think we all had a nervous breakdown or two or three-I kept telling my mom to FedEx my dignity back to me. But the most awful days I had were the most memorable. I look back and I know it was the most spectacular experience that I’ve had as a man, not even just as an actor.”

Boal’s on-the-ground experiences as a journalist in Iraq familiarized him with the specifics of EOD operations, like the protective suit worn by the team leader when he needs to gets up close and personal with a bomb. “There is a whole ritual to unpacking the suit,” says Boal. “Getting into the suit signifies the moment when the war becomes a solitary encounter between one man and a deadly device that’s been created with the express intention of causing harm. Once the team leader is in it, there’s no going back. He faces that lonely walk down to the bomb and it’s just him and this suit.”

Made of Kevlar fabric with ceramic plates, the suit is designed to protect the wearer from the impact of a blast, but it cannot withstand the largest explosions. “We thought of it like a suit of armor that a knight would wear in medieval times,” says Boal. “They have to put on, because it’s the only thing they have, but it certainly doesn’t offer foolproof protection from the enemy.”

Renner spent significant time wearing the suit for his role. “My feelings about the bomb suit are mixed,” he says. “You’re definitely alone once you get into it, but there’s something really peaceful about that. I felt like that was a womb for James. That’s the only time when he really felt safe, as a human being, not just as a soldier.”

Still, the actor says he had a love-hate relationship with the protective outfit. “It’s heavy, it’s hot, it’s hard to move in, but it put me right in the moment. Just the idea of getting into it-I wanted to dry heave whenever they said it was time to get suited up. I started sweating instantly and I knew I wasn’t going to get any hotter than I was in the first 30 seconds.”

For Guy Pearce, who plays the doomed Sgt. Matt Thompson, the bomb unit’s first leader, wearing the suit intensified his admiration for the members of the real EOD squad. “Our suit weighed about 70 pounds and I think the ones they actually wear are about 140 pounds. The heat was pretty intense, so you’re always on that edge of feeling faint. Maybe the adrenaline actually enables them to get through it, because it’s a life or death situation. I don’t know how they manage to be so dexterous in the fine work they have to do.”

Once the movie moved into post-production, renowned sound designer Paul Ottoson, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his work on Spiderman 2, went to work layering in the thousands of sounds that sound mixer Ray Beckett had recorded in Jordan. “From a sound perspective, this movie was incredibly difficult and unusual, definitely the hardest I ever worked on, because the score was very spare and ambient and there was so much detail in the sound. Practically every frame of the movie has a sound attached to it-it’s wall to wall sound-to give you that feeling that you are in a real war,” says Ottoson. “Every single sound of the movie is an organic base to it. We didn’t use any synthetic sounds because they are kind of unnatural, thin, slicing sounds. It is easier to get synthetic sounds to be loud. Staying organic the entire movie was difficult but we did it, because in the end it helped tell the story best.”

In the end, Boal hopes audiences will come to appreciate the sacrifices made daily by American troops. “If there is a message to the movie, it is that there’s a high price to heroism,” says Boal. “We see men who do these extraordinary things on TV and read about them in the newspaper. They get a medal pinned on their chests, but what we don’t often know is the interior life of these men. It’s not to say that everybody who’s a hero gets lost to war, but it’s a high price to pay to be a hero. James is a genuine hero, but his heroism doesn’t translate into personal happiness. He’s so damaged that he can’t see any outcome for himself other than disarming bombs.”

US Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal: Fast Facts

In 2004, there were only about 150 trained Army EOD techs in Iraq.

The job was so dangerous that EOD techs were five times more likely to die than all other soldiers in the theater. That same year, the insurgency reportedly placed a $25,000 bounty on the heads of EOD techs.

Bomb shrapnel travels at 2,700 feet per second. Overpressure, the deadly wave of supercompressed gases that expands from the center of a blast, travels at 13,000 miles an hour-at a force equal to 700 tons per square inch.

Separations and relationship troubles are so common among EOD teams that soldiers sometimes joke that EOD stands for ‘every one divorced.”

Bomb-disposal teams were first created in World War II. Starting in 1942, when Germany blitzed London with time-delayed bombs, specially trained U.S. soldiers joined British officers who diagrammed the devices using pencil sketches before they attempted to defuse them with common tools.

Bomb techs are trained at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. The Army looks for volunteers who are confident, forthright, comfortable under extreme pressure and emotionally stable. To get into the training program, a prospective tech first needs a high score on the mechanical-aptitude portion of the armed forces exam. Once the school begins, candidates are gradually winnowed out over six months of training, and only 40 percent will graduate.

Production notes provided by Summit Entertainment.

The Hurt Locker

Starring: Jeremy Renner, Anthony Mackie, Brian Geraghty, Ralph Fiennes, Guy Pearce

Directed by: Kathryn Bigelow

Screenplay by: Mark Boal

Release: June 26th, 2009

MPAA Rating: R for war violence and language.

Studio: Summit Entertainment

Bdx Office Totals

Domestic: $17,017,811 (34.6%)

Foreign: $32,212,915 (65.4%)

Total: $49,230,726 (Worldwide)