About the Production

Director Anne Fontaine has long been fascinated by the figure of Coco Chanel. “It was not so much the fashion as the characteristics of this exceptional woman that interested me,” says Fontaine. “I had been particularly touched by the fact that she was a self-made person. This girl, coming from the heart of the French countryside, poor, uneducated, but endowed with an exceptional personality, was destined to be ahead of her time.”

Years after her imagination was first sparked, the opportunity to make a film about the legendary woman presented itself. “I had to think whether it was possible to stick to the first period of her life-the training years, what had happened before Chanel, herself, understood her dazzling destiny,” the director explains. “So, I went back and read her biography by Edmonde Charles-Roux, Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion, and Fame. The other imperative condition was to find an actress to embody such a character, and not someone who would ape or make a pale imitation of Chanel.”

Fontaine found Chanel personified in Audrey Tautou. ”On my first encounter with Audrey, I was struck by her will, her audacity, and the density of her gaze that goes through you,” Fontaine recalls. “Chanel looked at everything. Her culture was not one of knowledge, but a culture of observation. I had not yet written a single line of the screenplay when I met Audrey, but I knew that if she gave me her trust and if the production agreed to stick to the years of apprenticeship, I could then embark on the adventure of my first period movie.”

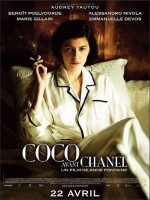

Audrey Tautou as Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel

Tautou was likewise fascinated by Chanel, and though the prospect of the role had long been hovering around her, she was captivated by Fontaine’s vision. “I was secretly hoping to get an offer with a particular point of view because the modernity of this character-her spirit, and the position she gave women-fascinates me,” says Tautou. “In addition, when Anne Fontaine explained how she intended to treat the subject, I immediately agreed.”

“Anne has allowed me to develop the nature of Chanel by searching different aspects of this role, by shading the emotions, being fragile and sweet and, at the same time, commanding and proud,” the actress continues. “The fact that a woman directs this movie is already a great advantage to express how difficult it was to be of `the weaker sex’ at that time. The intelligence of Anne Fontaine, her finesse, her global vision of the character and the story have been of utmost importance in her direction of the film.”

To successfully complete this ambitious project and faithfully portray Coco Chanel’s formative years, Fontaine was determined to assemble accomplished and acclaimed creative department heads. “It was the first time I was doing a period movie, so I wanted to work with technicians who were experienced in their respective fields,” she says.

Fontaine worked at length beforehand with her key crew members and proposed a survey of various great films from the time period in which the story is set. “Some are still classics, others were made by talented directors but are now considered old fashioned,” says Fontaine, adding, “The historical film is a very tricky genre because it is easy to fall into the trap of flirting with the conventions of a TV movie. From the outset, we had to take a hard-line attitude against the weighty, picturesque drawbacks of the period film.”

Production Designs

The production designer, Olivier Radot, was responsible for the sets in The Lover, Queen Margot, Lucie Aubrac and Gabrielle (which won the French César Award 2006).

“From our very first meeting, Olivier Radot appealed to me with his corrosive vision for the design of the sets,” she says. “I immediately felt we would be esthetically in agreement.”

Radot studied the life of Coco Chanel at length. “You must be careful to always focus more on the subject than on the period, and dedicate the world you create to the story, the sentiments and the director’s viewpoint,” says Radot. “That’s what gives a film substance. Instead of just copying the archives, I prefer to interpret, transpose, and feel free to keep the essence, the sensation. In any case, very few documents show Chanel during her years of apprenticeship. What I found most interesting in the end was to trace back to the source to find what had influenced her creation. We paid particularl attention to the sets for the orphanage and Aubazine at the beginning of the film, emphasizing the graphic, black and white aspect. The Aubazine uniform, with its black skirts and white blouses, also influenced her style. This starkness resurfaces at the end when Coco Chanel watches a triumphant fashion parade from the steps of the Maison CHANEL.”

Fontaine wanted the initial sets-the orphanage where she grows up, the cabaret in Moulins where she and her sister perform-framed in tight shots to create a sense of oppression. Then, liberty is made manifest when Coco arrives at Etienne Balsan’s château at Royallieu, which is a complete contrast to the severity of Aubazine. “We visited dozens of chateaux but eventually chose the first place we had seen!” Radot recalls. “Some were too ornate, others too pompous. We eventually chose the 18th-century château of Millemont in the Yvelines, as its white exterior with its chic simplicity could have inspired Coco. It was in these surroundings of Balsan’s that she discovered the world.”

The other concern the filmmaker shared with her production designer was finding locations that would enable them to shoot the film entirely in France. “Chanel embodies French elegance,” says Radot. “Her character is so Parisian that it would have been a shame not to shoot in France.”

Fontaine and Radot also collaborated on finding creative ways to bring naturalism to the atmosphere depicted in the film. “One of Anne’s qualities is to reject resorting to futile conventions,” Radot explains. “For the more spectacular scenes with a lot of extras, she prefers natural, true conditions to ultra-wide frames where considerable means are splashed over the screen for maximum effect. There is greater sensitivity when you feel some things are going on outside the frame. Anne is more into miniature and naturalistic effects than ostentation. In fact, hers is a very contemporary approach. Similarly, we understated the picturesque image of the `beuglant’-the rather coarse, colorful, thigh-slapping cabaret. I modeled it more on the American Café in Paris, with its dark wood paneling. We felt we had to tone down a place that was going to act as a setting for Mademoiselle Coco Chanel.”

The payoff for Radot was seeing the complete vision come alive. “I remember the day we filmed in the milliner’s workshop, the first Parisian set, which was the setting for Chanel’s initial success,” he notes. “When I saw Audrey Tautou wearing a new fingerwave hairstyle, with a cigarette at her lips, adjusting the trimmings of a hat, I had an impression I was really looking at Coco Chanel. It was incredible!”

Costume Designs

To create the critically important costumes for the period of Chanel’s life depicted in the film, Fontaine turned to Catherine Leterrier (French César Award winner in 2000 and 2004), who demonstrated her talent working with Fontaine herself on her previous film, The Girl From Monaco (La Fille de Monaco), as well as collaborating with such acclaimed filmmakers as Alain Resnais, Louis Malle, Robert Altman, Luc Besson, Jonathan Demme, André Téchiné, Bertrand Blier and Ridley Scott. Leterrier started her career in fashion (she graduated from the École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Haute-Couture Parisienne) before branching into the cinema and becoming one of the most sought after costume designers in the movie business.

“The whole crew was adamant that we should avoid all the traps of imagery, representation or the picturesque, in particular where costumes were concerned,” Fontaine says.

“The aim was not to make a movie about the history of fashion,” Leterrier says. “We occasionally had to take liberties with time. To fit in with the storyline, the famous striped mariner’s sweater worn by Chanel in the legendary photos of the 1930s appears earlier in the movie, in the scene where Coco is walking along the beach with Boy and notices the sweaters of the fishermen as they pull in their nets. At another point, as Anne wanted me to imagine how the world-famous CHANEL bag originated, I drew a quilted sewing pouch in the shape of the bag, and had it made out of an old, black, flecked cotton canvas that peasants’ clothing used to be made of, as if the young Coco had made it out of a remnant given to her by her aunts.”

A key element of the costume design was to show the influences that shaped the style of CHANEL. “In fashion, every designer has their own line, color and material codes,” Leterrier continues. “CHANEL’s is instantly recognizable. What Karl Lagerfeld did in adapting the style of CHANEL to the future, I did backwards towards the past. I went back in time, designing the first models that Chanel might have created and which could have fashioned her style. The style of CHANEL is distinctive in its cut, the supple hang of its fabric and the perfect simplicity of its finish. The costumes designed for the film had to be up to the exacting standards of Haute Couture.”

Leterrier set up a temporary workshop for the movie, complete with dressmakers’ apprentices and lead hands, that worked full-time to fabricate the extensive costume demands for the film. “For the scenes where there are a lot of extras-the dance hall, the racecourse, Emilienne’s theatre etc.-we made, in addition to the costumes, nearly 800 different hats, created by two great milliners, Stephen Jones and Pippa Cleator. Before she made dresses, Chanel was a successful milliner, and her hats were more architectural and less fussy than those of the times. She made fun of the over-ornate hats that some women wore: ‘With that on their head, how can they think!’”

One particular challenge was integrating the more contemporary looks with the era in which Chanel introduced them. “The difficulty for me was to contrast the elegance of Chanel’s simple and fluid style with the fashion in 1900,” Leterrier explains. “I wanted to keep its beauty, with the blouses that enhanced the bust, the ribbons, lace, feathers and frills, whilst showing its excessive, showy and formal side so I could contrast it with CHANEL’s pure, flowing lines.”

For the final catwalk scene, Leterrier chose authentic models and jewelry from different periods in the Conservatoire of CHANEL. “The collaboration of CHANEL was indispensable to us, particularly for the final sequence where it was unthinkable not to have dresses by the CHANEL label,” says Fontaine. “In this sequence, all the dresses come from the Chanel Conservatory of CHANEL. I met Karl Lagerfeld several times; we showed him the sketches of the clothes Catherine Leterrier was making.”

To accessorize, the costume designer went on a scavenger hunt. “I hunted down the cotton braids, silk ribbons, buttons and other period accessories at flea markets and antiques dealers,” she remembers. “I even found a platinum and diamond necklace that had belonged to Mademoiselle Chanel at the Louvre des Antiquaires. In the film, this magnificent piece adorns Audrey Tautou’s graceful neck in the restaurant scene where she appears in a black sequined evening dress. Audrey showed great interest in the costumes, and during fitting sessions I watched her concentrate and suddenly metamorphose into Coco Chanel.”

Leterrier also relished integrating CHANEL elements into the men’s costumes. As she notes, “For Balsan’s wardrobe, I introduced tweed, which was another of CHANEL’s codes, and for his dressing-gown I asked Bianchini-Ferier, in Lyon, to reprint a silk fabric with an old design by Raoul Dufy depicting horses, which I had recolored.”

“My whole team, from lead hand down to trainee, was highly motivated and everyone found it awe inspiring to be making the costumes for Coco Chanel. It’s like doing Molière when you are an actor, for us, CHANEL is mythical!”

To shoot the film, Fontaine enlisted Christophe Beaucarne, whose work behind the camera can be appreciated in Paris, directed by Cédric Klapisch; Paint or Make Love by the Larrieu brothers and Jaco Van Dormael’s latest movie. “Christophe Beaucarne is a director of photography who will rise to any challenge,” Fontaine enthuses. “He has an amazing combination of intelligence and humor.”

Cinematography

Fontaine collaborated with Beaucarne to always reflect Chanel’s point of view in the cinematography. “The movie had to be like Coco Chanel’s character,” she explains. “She was a young woman who never stayed still. The filming had to pulsate and the camera required a certain sensuality and movement. We often used a hand-held camera to shoot. Christophe Beaucarne is a very physical, adaptable cameraman. The openness and integrity with which he approached this film helped me a lot.”

The moviemaker and her director of photography decided to shoot with two cameras to keep up the rhythm and pace and give the scenes a certain modernity. “The idea was to always accompany Chanel in her evolution and follow her inner adventure, her love story. The film is almost always shot from her viewpoint, except for two or three sequences linked to her feelings,” says Beaucarne, adding, “With Anne, we refused to resort to the complacency and contemplative side of period movies; there are no descriptive crane movements lingering on the grandeur of the set with its pageants of horse-drawn carriages and cohorts of extras! The luxury of the movie is precisely in not flaunting our resources. In the race course scene, for example, there are 300 extras on screen, but we have no protracted descriptive shots. The main thing was to portray the atmosphere at race courses in those days. They were packed because it was one of those places where you had to be seen.”

Beaucarne chose to shoot the scenes at Royallieu in sunlight to accentuate the château’s dazzling whiteness. “Although she was born in the country, Coco was shut up in the orphanage at a very early age,” Beaucarne describes. “She then lived in a maid’s garret and a smoky cabaret, and suddenly, in the château, she discovered the wonders of nature. I tried to transcribe, via the framing and lighting, the sense of liberation Chanel must have felt there. After the severity of Aubazine, where we used a lot of black and white, we wanted sunshine, wider frames and a festive atmosphere that corresponded to Balsan’s personality. For this bright and light-hearted side, with the set designer Olivier Radot, we had The Great Gatsby in mind as one of our distant references.”

Beaucarne also relished reinterpreting Cecil Beaton’s iconic photos of Chanel, “such as Chanel in her workshop, for example,” he says. “In the final sequence in the stairwell of the Maison CHANEL on rue Cambon, the lighting I devised plays with residual light to give an elliptical feel to the scene, where the fabulous models on the catwalk are seen as reflections in the mirrors only. What was important here was to suggest Chanel’s intimate vision.”

Beaucarne confesses he was inspired by the extremely photogenic quality of Audrey Tautou. “I played on the contrast between the lightness of her skin and the darkness of her eyes and hair,” he reflects. “Her eyes steal the show… I avoided putting direct lighting on her to emphasize a certain soft yet contrasted side, a subtle touch that also let me obtain the contours I wanted for the costumes and materials. Audrey identified keenly with her character, fully grasping Chanel’s strong, determined spirit. It was a real delight to film her, for in addition to her good looks, Audrey pays great attention to technique. Her variations of gesture and movement in her acting are extremely precise.”

The final element-the music-fell to Oscar-nominated composer Alexandre Desplat (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, The Queen), who has written the soundtrack to more than 60 films. This gifted and prolific composer divides his time between French productions (Largo Winch, The Singer, The Valet), and international films. His inspired soundtrack for The Beat That My Heart Skipped won the César Best Music award in France and a Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival.

Like the physical aspects of the production, Fontaine and Desplat collaborated to reflect Chanel herself in the music. ”I think Coco Chanel had a pair of eyes that were very particular in real life, and so does Audrey Tautou,” Desplat comments. “They both have the same gravity and intensity. She is not just watching. She’s scrutinizing and really intensively watching. She’s grabbing a detail, a colour, a shape that become something of her own once it goes through her filter. So, I guess that’s the main thing that I tried to do with the score: always keep the intensity of her character, not just the fun. She has a lot of courage and a desire to change things. And that’s something I like a lot-when artists show the way, a different way, another way, not just follow the flow of the river. My music should follow this.”

The final effect, Fontaine hopes, will be a complete interpretation of a young woman on the cusp of inventing herself. “What particularly interested me was to watch Coco build her destiny before our eyes, by inventing as she went along,” she says. “Nothing was programmed with her; she is not pursuing a career to reach success; she is inventing. She does not have the ambition or the tools to conform to the world of the bourgeoisie-its doors were closed to her-so she drew attention to herself to start at the top of provocation. She does not want to abide by this world but to adapt it to her own personality. She also likes to take risks. I liked very much the idea that she was a clandestine when she started her journey in the world. When she arrives to Royallieu, Balsan forbids her to leave her bedroom. She forged her emblematic image upon the secrets of her origins; she always embellished the story of her childhood.”

Production notes provided by Sony Pictures Classics.

Coco Before Chanel

Starring: Audrey Tautou, Alessandro Nivola, Marie Gillain, Benoît Poelvoorde, Emmanuelle Devos, Roch Leibovici

Directed by: Anne Fontaine

Screenplay by: Anne Fontaine, Edmonde Charles-Roux

Release Date: September 25, 2009

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for sexual content and smoking.

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $5,714,396 (16.3%)

Foreign: $29,318,844 (83.7%)

Total: $35,033,240 (Worldwide)