Based upon Mark Millar’s explosive graphic novel series and helmed by the stunning visualist director Timur Bekmambetov–creator of the most successful Russian film franchise in history, the “Night Watch” series–“Wanted” tells the story of one invisible drone’s transformation into a dark avenger. In 2008, the world will be introduced to a superhero for a new millennium: Wesley Gibson.

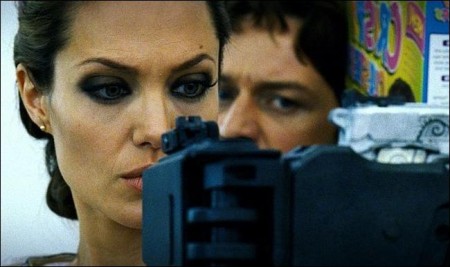

25-year-old Wes (James McAvoy) was the most disaffected, cube-dwelling drone the planet had ever known. His boss chewed him out hourly, his girlfriend ignored him routinely and his life plodded on interminably. Everyone was certain this disengaged slacker would amount to nothing. There was little else for Wes to do but wile away the days and die in his slow, clock-punching rut Until he met a woman named Fox (Angelina Jolie).

After his estranged father is murdered, the deadly sexy Fox recruits Wes into the Fraternity, a secret society that trains Wes to avenge his dad’s death by unlocking his dormant powers. As she teaches him how to develop lightning-quick reflexes and phenomenal agility, Wes discovers this team lives by an ancient, unbreakable code: carry out the death orders given by fate itself.

With wickedly brilliant tutors — including the Fraternity’s enigmatic leader, Sloan (Morgan Freeman) — Wes grows to enjoy all the strength he ever wanted. But, slowly, he begins to realize there is more to his dangerous associates than meets the eye. And as he wavers between newfound heroism and vengeance, Wes will come to learn what no one could ever teach him: he alone controls his destiny.

From Comic Book to Screen

“Cool as hell,” “unique,” “experimental,” “ironic” and “creative genius” are just some of the words used to describe Russian-born director Timur Bekmambetov, who hails from the city of Guryev in Kazakhstan. Bekmambetov’s vision has landed him his first English-language film, in collaboration with astute producers and an award-winning cast and crew, all under the aegis of a large American movie studio.

Just how did that happen? Perhaps a little background… The year 2004 saw the release of Bekmambetov’s film Nochnoy Dozor (or Night Watch). The film was budgeted at $1.8 million but grossed more than $16 million in Russia alone, making it more of a hit in his own country than The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. The sequel to Night Watch (the first installment of the trilogy), Day Watch, was released in Russia in early 2006. Again, the film was considered low budget (costing just $4.2 million) and became a juggernaut-grossing nearly $40 million in Bekmambetov’s home country.

About the same time, executives at Marc Platt Productions had come across Mark Millar and J.G. Jones’ first issue of their comic book series “Wanted” and immediately thought the dark and inventive tale had huge cinematic potential…but the subject matter (a covert band of super villains who has split up the world into factions) needed an offbeat spin. They sought an exciting, creative new filmmaker who thought beyond limits and, after seeing Night Watch, they knew they’d found their man. If Bekmambetov could create such a visually stunning movie on such a low budget, producers reasoned, there would be no holding back the auteur’s energetic point of view and dark sensibility when given a large-scale budget and the vast resources available to a studio-made film.

Producer Marc Platt comments, “The cinematic experience of Timur’s work and the visual language employed by him are so unique, eye-popping and extraordinary, I knew his was a voice that had to be heard. I had never experienced visual images in that way. I thought by matching him and his ability to create a completely new world with this material, we could create something exciting, experimental and yet accessible for audiences all over the world.”

Bekmambetov’s producing partner, Jim Lemley, adds, “We spent two years getting from the first draft of the script to the shoot. It was important for us to push through a comfort level of what had been seen on film before and come up with ideas-no matter how outlandish they seemed on paper-that could visually blow the audience away.”

Regarding his trust in the director’s unique vision, Lemley concludes, “You could put three people in a room, give them the same camera and ask them to take the same shot. Timur’s image would be amazing.”

Of his thoughts on visual imagery, Bekmambetov remarks, “It is like 100 ideas are going on inside my brain, all fighting to come out. What happens is this makes a new style, maybe something that no one has seen before. I want to put the audience in the action-in the middle-so that they go on a journey with the character, not just sit and watch.”

The director’s mantra seems to be a fantastic realism on each of his projects. He believes there should be a realistic base to every action, every emotion, no matter how outlandish the circumstances. As a director, his attention to detail gives him something on which to focus-a solid way into each scene.

“Making my first film in English is not so different from my other movies,” claims the director. “I just try to communicate with the audience, fall in love with them in a way and make a good movie for them-be a good storyteller for them.”

The director’s approach to filmmaking and skewed tone hardly changed with his move to an American-studio and English-language production. Platt adds, “Bekmambetov brings a very strong sardonic sense to his work, which was very present in all of his previous films. Not in a silly, broad way, but in a dark, comedic way that constantly undercuts the earnestness of the proceedings. It is the irony that he brings to the project, both narratively and visually, that gives Wanted a very unique tone.”

That black humor is also present in the project’s source material, Millar and Jones’ graphic novel of the same name (originally published as a six-issue limited series). More than just acquiring the property that was one of the best-selling independent comic books of the last decade, the filmmakers were also keen on obtaining the blessing of the original creators.

At the time Millar had sold the movie rights to Universal, he and Jones were only up to the second issue. So, while Millar was finishing the series, the studio had almost finished the first draft of the screenplay.

With two parties writing independently, both projects took on separate lives. Millar comments, “I was relaxed about this, because the comic book and movie were two distinct entities. Regardless of what they changed, my book would be untouched. But I was pleased to see them going back again and again to the source material, and once they had my entire book in a complete form, subsequent drafts by other screenwriters incorporated pretty much all of the main material. They dropped the super villain backstory I had in the original book, but everything else works very well.”

Before advancing on separate paths, both the graphic novel and graphically violent screen version of Wanted started in the same place (the first one-third of the screenplay mirrors the first two chapters of the series…but then diverges). The comic writer feels that although the stories take place in very different places, the tone, the characters and basic narrative remain the same in both versions.

Millar observes, “The first 40 minutes of the film are pretty much identical, scene for scene, to the book, and I was pleased with that. This wasn’t the case with the first draft, but once Timur was attached, he really just embraced many of the darker aspects of the material. I thought they might drop some of the slightly more edgy material, but captions, voiceovers, dialogue and entire sequences were lifted straight from the book. I was so pleased to see that. One of my favorite scenes that was transplanted was the opening scene where, suddenly, this guy sees a dot on his head, takes out his guns, jumps out the window and starts chasing after these assassins. It’s beautiful that the way it’s actually shot is almost panel for panel like the comic book.”

Not only was the writer impressed by the filmmakers’ attention to detail, but by how the screenwriters and Bekmambetov expanded upon key scenes from the first two chapters in his series. Says Millar, “There were a few scenes where I only had a couple of panels to play with, because you don’t really have a lot of room in a comic book. Timur and the guys fleshed them out and made them into cool scenes with gigantic chase sequences.

As a nod to die-hard “Wanted” comic aficionados, Millar acknowledges, “There’s all these little `Easter eggs’ that fans of the book will be able to pick up on. The second chapter, for example, is called `F–k you,’ and Timur had a little laugh with this by incorporating the words on a computer keyboard flying toward us when the main scene was brought to life in the movie.”

Producer Platt adds, “Mark really embraced Timur. The comic is fantastic and gutsy and it has a real edge to it, and that’s what we wanted to build into our script. We didn’t want to make something run-of-the-mill…We wanted to roll the dice and try for something special. Where the script follows the comic book, we didn’t change a word of it. But, of course, the movie is its own thing. Millar backs it, and that’s important to us as filmmakers.”

Not only was it important for the director to honor the inventiveness of the source material, he intended to respect Wesley’s search for reality in a world of deceit. “This is really a story about truth,” sums Bekmambetov. “Wesley is trying to escape from a world where people lie and find people who tell the truth. Along the way, he finds you can’t do anything about fate, but you can destiny. You choose and you steer your destiny. Something everybody is trying to do.”

Weaving the Design: A Brave New World

In both the comic book and the screenplay of Wanted, the characters move about in a world that, at first glance, resembles ours-but on closer look, that world is tweaked, askew, just this side of real. The characters in it don’t just move, they inhabit it in a powerful, superhuman way.

To help realize this vision, filmmakers turned to a double Oscar-winning production designer, who is quite familiar with creating an on screen version of heightened, “just this side of real” reality: John Myhre.

Myhre offers, “I was seduced by Bekmambetov in about 15 seconds-he’s just one of the most creative people I’ve ever met. It’s so fulfilling to talk to another filmmaker and have them so enthusiastic and so full of good ideas…he’d have 3,000 ideas for everything, and they’d all be great.”

Shooting in Prague

Although the film takes place in Chicago, Prague was chosen as the site of Wanted’s principal photography. Multiple reasons played into the choice. Because of the amount of filming taking place in Chicago at the time production was slated, space was tight. To make up for that shortfall, an inordinate amount of construction would have been necessary to build interiors, and this simply did not make financial sense.

Platt comments, “Although it’s been somewhat of a challenge to shoot a film like Wanted in Prague-to re-create bits of Chicago-it was the best place to film. Shooting space was plentiful, and its proximity to Moscow-where our effects were being done-was a bonus. We simultaneously shot in Prague and completed effects in Moscow. We’d shoot and cut, and then dispatch it to Russia for effects.”

Bekmambetov had worked in Prague for two years before returning to shoot Wanted, so he was exceedingly familiar with the choices of locations available-another benefit. The look of the Chicago interiors/exteriors was to be post-industrial, a mixture of steel beams, rivets, girders and basic solid architecture and brickwork, all of which needed to be combined by Myhre and his team of talented artisans into a homogenous whole. Per locations supervisor MICHAEL SHARP: “We needed a space with a minimum of three stories to house the Loom, but we also needed to shoot as many of the interiors as possible in that one space. We ended up in an old sugar factory that was built in 1914 and closed as a plant in 1956. It had quite a neutral architecture to suit the different stages that the film goes through, but we also had the great depth and adequate space to use it as five different locations, including the magnificent Loom of Fate set. Every piece of floor in the factory was shored up and strengthened underneath, so that we could still play with two-and-a-half tons of equipment and toys to suit the sequences-without having to change the look from the top.”

Reproducing bits of Chicago in a Belle Époque sugar factory provided Myhre with a few challenges: “We did a little shifting and pulled some of the story inside, so we could be smart and economical when it came time to shoot in Chicago. Bekmambetov wanted the film to have a very American feel about it, while also embracing some European sensibilities, which shooting in Prague provided. We were able to synthesize a bit of a hybrid and take the best of all worlds, again, mixing the old with the new, a theme that runs throughout the whole of the movie.”

As Bekmambetov wished to shoot and create effects in short order, it was even more important for the art and visual effects department to stay in sync with constant communication. Visual effects producer JON FARHAT explains, “We really tapped into the talents and resources of John Myhre and we tried to let his designs drive the look for our visual effects, drive the modeling and the creation of our Fraternity, the monastery and the look of all of the interiors.”

The Loom of Fate

As mentioned, one of the most prominent sets in Wanted is the centerpiece Loom of Fate. At its heart, the Loom is a very simple structure, but the threads that it weaves determine the fate and destiny of the citizens of the world.

Bekmambetov and the screenwriters fashioned a mythology as background to the group of assassins and how they function-tapping into global mythologies that contain symbolism and imagery of weaving. In the world of Wanted, centuries before we meet Wes and the Fraternity, weavers of fabric started to decipher a code within their work, messages that spoke to the state of the world. A flaw in the fabric signaled a flaw in the world. Eventually, these flaws became the dictates to the earliest member of the Fraternity. Fate designates that someone must be killed in order for the world to carry on in a balanced way-an assassin is chosen to carry out the order of the Loom, theoretically correcting the path of the world and restoring its balance.

Fabric is woven with perpendicular threads, the weft (vertical) and the warp (horizontal, woven back and forth on a shuttle). The flaws on the Loom’s weave result from a skipped thread-these mistakes are counted and form a binary pattern, which is converted into text, and that text spells out a death order.

Production designer Myhre admits, “I always love learning something new, and the whole world of textile factories and looms was completely new to me. The way that thread is manipulated to create infinite numbers of fabrics is astounding.”

The Loom of Fate plays such a pivotal role in the movie that Myhre co-opted the theme of “weaving,” subtly incorporating it into the overall design: “The idea is that everything is woven together from the very beginning. Wesley’s office is one of those horrible places comprised of lots of little cubicles with woven fabric on the walls. Outside the Fraternity the telephone lines are crisscrossed, like tumbles of spiderwebs. It’s all the way through the film, just in a very unobtrusive way.”

Platt comments, “In the Old Testament, there is a whole system of numerology where words are prescribed numbers and those numbers represent a code. In many ways, the mythology created for this film is no different.”

Production took inspiration from the more than 100 different textile factories within a two-hour ride from the center of Prague. Field trips were taken to view the looms and study how fabric is manufactured. Looks from different plants were combined and reproduced, and the Loom of Fate is a final amalgam of several of these plants’ looms.

The physical Loom itself was assembled together from rentals and newly constructed pieces, and the combination of black metal, worn wood and spare brass fittings ends up resembling a machine from the turn of the 20th century (appropriate, as the Fraternity’s current headquarters is said to have been built in Chicago at that time). In keeping with the film’s subtle and overall mix of old and new, the art department also added some offbeat, modern touches, such as magnifying glasses around the edges of the Loom to refract light to the tables underneath.

More looms, but on a lesser scale, were incorporated into the design of the Fraternity’s shop floor (in addition to being the group’s headquarters, it is also a producing textile mill). Myhre comments, “The shop floor looms are partially threaded from the ceiling overhead, and they form these huge fantastic shapes-when you put a couple of them together, you start getting a very Gothic-looking arch. It gives the feel of an old church or a castle, and this castle feel is evident in the Chicago Fraternity. The building is fronted by two enormous wooden gates; to enter, you have to drive over a bridge over a small moat.”

Costumes and Makeup

BAFTA Award-winning FRANCES HANNON was brought onboard to design the hair and makeup for the film. The passage of time and the transformation taking place in Wes needed to be realized on screen-the office drone grows into the sharpened assassin. Hannon explains, “The main challenge I faced was how to take the character of Wesley from A to Z while keeping the changes subtle and believable. He not only changes how he looks, but how he is inside, and we wanted to show that visually, too.”

That transformation didn’t come without its share of bruises…literally. During Wes’ training period, he is subjected to several beatings-something Hannon knows how to show on screen, having worked on several thrillers and action films (including The Da Vinci Code and Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life). But, as always, these choices were run past someone else first. She clarifies, “I had to discuss things with the director, like where on the face a hit will be, what type of hit it is and how long he wants it to last. I can’t put a big, fat, black eye on an actor if we need to lose it the next day, so I’d maybe put on a small cut that could feasibly heal. Bekmambetov knew exactly what he wanted to see, where he wanted it and when he wanted it, although we often developed ideas on the move.”

Costume designer Varya Avdyushko has previously worked with Bekmambetov on Night Watch and Day Watch and is used to his ever-flowing ideas. She says, “Bekmambetov generates a lot of ideas, sometimes up until two hours or even less before we’re due to shoot a scene. However, because I have worked with him before, I am very used to this way of working. The fountain of ideas he has is very unique.”

Upon receiving the script, Avdyushko broke it down to understand the characters-she created behaviors and habits for them, a detail that she hopes is reflected on screen. Per Avdyushko: “We tried to find a little quirk for every character, particularly the Fraternity. For example, The Butcher, who is a brutal bandit, wears bright yellow sneakers. He wraps them in cellophane to prevent blood from spilling on them. The Gunsmith would never require excess; he’s very neat and precise. He only carries what he needs. The Exterminator deals with rats a lot, so on his belt we have jars and various tools he could use to carry his rats with him.”

The costume designer also experienced a close collaboration with production designer Myhre: “He showed me the colors, textures and symbols he wanted to use in his sets, and we incorporated these into our costumes.”

That creative theme of old and new carried throughout the film is also reflected in the clothes the characters wear. Avdyushko offers, “We used elements in the costumes from places like Mexico and modern-day America, but for small details such as buttons, we utilized antiques. They’re an important part of the character, of who they are and how they live their lives.”

Welcome to Assassin Mode.

This is a trait shared by all in the Fraternity. It enables them to see things more clearly than a normal person. With the world at a snail’s pace, the assassin has more time in which to think, decide and act. While in the mode, the fighter can discern what is happening at any given moment with a jewel cutter’s precision-thus making life-altering decisions with ease and clarity.

The Assassin Mode was a complex notion to try to achieve visually, and Bekmambetov wanted it to work within the Wanted bounds he had established: that every effect needed to have an emotional basis. Ergo, if Wesley was to be in Assassin Mode, the director wanted the audience to be in Assassin Mode as well, not merely looking at it as an observer. And although all Fraternity members have the ability to go into the mode, the audience would only see it from Wes’ point of view.

McAvoy explains, “Within the mythology of the film, the senses of the assassins in the Fraternity become heightened as their hearts pump in excess of 400 beats-per-minute. They’re not supermen and they don’t have superpowers, but they see things faster and clearer-but making a decision that quickly, compared to everyone else around them, might be seen as something superhuman.”

Bekmambetov likes to push his boundaries-so how about defying the laws of physics? Why not? So he and DP Mitchell Amundsen fashioned a shot specific to the Fraternity that enabled them to bend bullets (again, to be augmented with visual effects). McAvoy explains the concept behind the technique: “The Fraternity members can bend bullets because they have non-rifled chambers and barrels in their guns-non-rifled means there’s no interior grooving which causes the bullet to spiral as its fired. So, in our theory, that means that if I swing my wrist like I’m taking a tennis shot, the bullet arrives at your target but in a curved trajectory-not a straight shot. You can bend around objects. Instead of moving to get a target in sight, you just move your arm.”

McAvoy and Bekmambetov spent a lot of time developing the actual on screen physical technique that would “bend bullets.” Their goal was to create an action that looked “cool, but functional…seamless, rather than apparent.” Several crew (from both Team Amundsen and Team Farhat) were also involved in quite a bit of research to create a move that-in both camera effects and visual effects-would look completely possible and completely within the grasp of reality. (Of course, don’t ask a science professor or physics expert about the plausibility of this…)

Jolie comments, “I’m probably the only person that found the bending of bullets the most difficult thing to do in the movie. It’s a little odd to try and talk about it seriously, but when Morgan Freeman’s character is explaining how it works, and because it’s Morgan saying it, you actually start to believe it.”

Production notes provided by Universal Pictures.

Wanted

Starring: James McAvoy, Morgan Freeman, Angelina Jolie, Common, Kristen Hager, Konstantin Khabensky

Directed by: Timur Bekmambetov

Screenplay by: Michael Brandt, Derek Haas, Chris Morgan

Release Date: June 27th, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for strong bloody violence throughout, pervasive language and some sexuality.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $134,327,125 (44.4%)

Foreign: $168,132,669 (55.6%)

Total: $302,459,794 (Worldwide)