What if mankind had to leave Earth, and somebody forgot to turn off the last robot?

That’s the intriguing and whimsical premise posed by Disney • Pixar’s extraordinary computer-animated comedy set in space, “WALL•E.” Filled with humor, heart, fantasy, and emotion, “WALL•E” takes moviegoers on a remarkable journey across the galaxy, and once again demonstrates Pixar’s ability to create entire worlds and set new standards for storytelling, character development, out-of-this-world music composition and state-of-the-art CG animation.

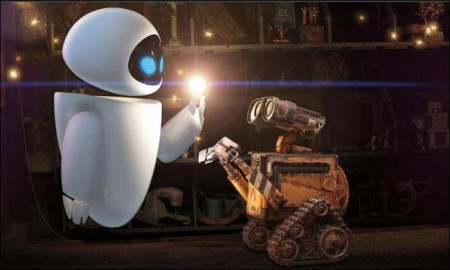

Set in a galaxy not so very far away, “WALL•E” is an original and exciting comedy about a determined robot. After hundreds of lonely years doing what he was built for, WALL•E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-Class) discovers a new purpose in life (besides collecting knick-knacks) when he meets a sleek search robot named EVE (Extra-terrestrial Vegetation Evaluator).

EVE comes to realize that WALL•E has inadvertently stumbled upon the key to the planet’s future, and races back to space to report her findings to the humans who have been eagerly waiting on board the luxury spaceship Axiom for news that it is safe to return home. Meanwhile, WALL•E chases EVE across the galaxy and sets into motion one of the most incredible comedy adventures ever brought to the big screen.

Joining WALL•E on his fantastic journey across the universe 800 years into the future is a hilarious cast of characters including a pet cockroach and a heroic team of malfunctioning misfit robots.

The ninth feature from Disney and Pixar Animation Studios, “WALL•E” follows the Studio’s most recent triumph, “Ratatouille,” which won an Oscar for Best Animated Feature, garnered the best reviews for any 2007 release, and was a box office hit all over the globe. The combined worldwide box office gross for Pixar’s first eight releases is an astounding $4.3 billion.

“WALL•E” is the latest film from Academy Award-winning director/writer Andrew Stanton, who joined Pixar in 1990 as its second animator and the fledgling studio’s ninth employee. He was one of the four screenwriters to receive an Oscar nomination in 1996 for his contribution to “Toy Story” and was credited as a screenwriter on subsequent Pixar films, including “A Bug’s Life,” “Toy Story 2,” “Monsters, Inc.” and “Finding Nemo,” for which he earned an Oscar nomination as co-writer. Additionally, he co-directed “A Bug’s Life,” executive produced “Monsters, Inc.” and the 2007 Academy Award-winning “Ratatouille,” and won an Oscar for Best Animated Feature for “Finding Nemo.”

Disney•Pixar’s “WALL•E,” directed by Andrew Stanton, from an original story by Stanton and Pete Docter, and screenplay by Stanton and Jim Reardon, is executive produced by John Lasseter and produced by Jim Morris (“Star Wars, Episodes I and II,” “Pearl Harbor,” “The Abyss,” and three of the “Harry Potter” films), who helped create some of the industry’s ground breaking visual effects during his 18-year association with ILM as president of Lucas Digital. Lindsey Collins, an 11- year Pixar veteran, serves as co-producer; Tom Porter is associate producer. Oscar-winning cinematographer Roger Deakins serves as visual consultant.

The voice cast includes funny man Jeff Garlin (“Curb Your Enthusiasm”), Pixar veteran John Ratzenberger (“Cheers,” “Ratatouille,” “Toy Story”), award-winning actress Kathy Najimy (“Sister Act,” “King of the Hill”), stage and film star Sigourney Weaver (“Alien,” “Gorillas In The Mist,” “Baby Mama”), and acclaimed four-time Oscar-winning sound designer Ben Burtt (“E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial,” “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade”). Comedian Fred Willard (“Best In Show,” “Back to You”) also appears in the film.

Out to Lunch: A Romantic Robot Begins to Take Shape

The idea for “WALL•E” came about in 1994 at a now-famous lunch that included Pixar pioneers Stanton, John Lasseter, Pete Docter, and the late storytelling genius Joe Ranft. With their first feature, “Toy Story,” in production, the group suddenly realized that they might actually get a chance to make another movie. At that fateful gathering, the ideas for “A Bug’s Life,” “Monsters, Inc.” and “Finding Nemo” were first discussed. “One of the things I remember coming out of it was the idea of a little robot left on Earth,” says Stanton. “We had no story. It was sort of this Robinson Crusoe kind of little character — like what if mankind had to leave earth and somebody forgot to turn the last robot off, and he didn’t know he could stop doing what he’s doing?”

Years later, the idea took shape — literally. “I started to just think of him doing his job every day, and compacting trash that was left on Earth,” Stanton recalls. “And it just really got me thinking about what if the most human thing left in the universe was a machine? That really was the spark. It has had a long journey.”

Stanton says he was heavily influenced by the sci-fi films of the 1970s. “Films like `2001,’ `Star Wars,’ `Alien,’ `Blade Runner’ and `Close Encounters’ – they all had a look and feel to them that really transported me to another place and I really believed that those worlds were out there,” he explains. “I haven’t seen a movie since then that made me feel that same way when we went out to space, so I wanted to recapture that feeling.”

In preparation for their assignment on “WALL•E,” Pixar’s animation team made field trips to recycling stations to observe giant trash crushers and other machinery at work, studied real robots up close and in person at the Studio, and watched a wide range of classic films (from silents to sci-fi) for insights into cinematic expression. Sticking to Pixar’s motto of “truth in materials,” the animators approached each robot as being created to perform a particular function, and tried to stay within the physical limitations of each design, while creating performances with personality. Alan Barillaro and Steve Hunter served as the film’s supervising animators, with Angus MacLane assuming directing animator duties.

Production designer Ralph Eggleston (“The Incredibles,” “Finding Nemo,” “Toy Story”) drew inspiration for the look of “WALL•E” from NASA paintings from the 50s and 60s, and original concepts paintings for Disneyland’s Tommorowland by Disney Imagineers. He recalls, “Our approach to the look of this film wasn’t about what the future is going to be like. It was about what the future could be — which is a lot more interesting. That’s what we wanted to impart with the design of this film. In designing the look of the characters and the world, we want audiences to really believe the world they’re seeing. We want the characters and the world to be real, not realistic looking, but real in terms of believability.”

Adding to the believability of the film is the way the film is photographed. Jeremy Lasky, director of photography for camera, explains, “The whole look of `WALL•E’ is different from anything that’s been done in animation before. We really keyed into some of the quintessential sci-fi films from the 60s and 70s as touchstones for how the film should feel and look.”

Stanton adds, “We did a lot of camera work adjustment and improvements on our software so our cameras were more like the Panavision 70 mm cameras that were used on a lot of those movies in the `70s.”

A World of Robots and Other Bots: The Who’s Who in WALL•E

WALL•E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-Class) is the last robot left on Earth, programmed to clean up the planet, one trash cube at a time. However, after 700 years he’s developed one little glitch — a personality. He’s extremely curious, highly inquisitive and a little lonely. WALL•E was one of thousands of robots sent by the Buy n Large corporation to clean up the planet while humans went on a luxury space cruise. He is alone, except for the companionship of his pet cockroach, affectionately known within Pixar’s walls as Hal (named after a famous 1920s producer, Hal Roach, and in homage to HAL from “2001: A Space Odyssy”). WALL•E faithfully compacts cubes of trash everyday, uncovering and collecting artifacts along the way. In fact, WALL•E has amassed a treasure trove of knick-knacks – a Rubik’s Cube, a light bulb, a spork – which he keeps in a transport truck he calls home. A bit of a romantic, WALL•E dreams of making a connection one day, certain that there must be more to life than this monotonous job he does every day. His dream takes him across the galaxy and on an adventure beyond his greatest expectations.

EVE (Extra-terrestrial Vegetation Evaluator) is a sleek, state-of-the-art probe-droid. She’s fast, she flies and she’s equipped with a laser gun. EVE, also called Probe One by the Captain of the Axiom (the enormous luxury mother ship which houses thousands of displaced humans), is one of a fleet of similar robots sent to Earth on an undisclosed scanning mission. EVE has a classified directive and she is determined to complete her mission successfully. She hardly even notices her new admirer WALL•E. One day, frustrated with not finding what she is looking for, she takes a break and makes an unexpected bond with this quirky robot. Together, they embark on an amazing journey through space.

M-O (Microbe-Obliterator) is a cleaner-bot programmed to clean anything that comes aboard the Axiom that is deemed a “foreign contaminant.” M-O travels speedily around the Axiom on his roller ball, cleaning the dirty objects he encounters. His biggest challenge comes on the day WALL•E shows up on the ship. M-O becomes fixated on the filthiest robot he has ever seen. A game of cat and mouse ensues as M-O attempts to wash years of garbage residue off WALL•E. However, as WALL•E tries to escape this pest, the two eventually become friends and M-O is soon WALL•E’s devoted sidekick.

AXIOM is the space-docked ship housing humans. Serving as the voice of the ship’s computer is Sigourney Weaver, who coincidentally made her motion picture debut in “Alien,” one of Stanton’s inspirations for the film. And since her character in “Alien” battled Mother, the ship’s computer, casting Weaver in the role was ultimately a nod to sci-fi for the filmmakers.

CAPTAIN is the current commander of the Axiom. Trapped in a routine, like WALL•E, the Captain longs for a break in the tiresome cycle of his so-called life. His uneventful duties are simply checking and re-checking the ship’s status with Auto, the autopilot. When he is informed of a long-awaited discovery by one of the probe-droids, he discovers his inner calling to become the courageous leader he never could have imagined and plots a new course for humanity. Jeff Garlin, part of the hilarious ensemble cast on the popular HBO series “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” lends his voice to this likeable character.

AUTO is the Axiom’s autopilot, who has piloted the ship through all of its 700 years in space. A carefully programmed robot in the form of the ship’s steering wheel, Auto’s manner is cold, mechanical and seemingly dutiful to the Captain. Unknown to all the Axiom crew, a hidden mandate exists in Auto’s programming. Auto is determined to execute these secret orders at any cost, regardless of the consequences for the inhabitants of the Axiom.

REJECT BOTS are the Axiom’s cornucopia of robots that perform every function imaginable to serve the ship’s passengers and keep them in the lap of luxury. However, even hundreds of years in the future, machines are still fallible. Robots that have malfunctioned are sent to the repair ward and branded with a red boot. WALL•E befriends this renegade group of reject bots, among them a Beautician-bot that fails to beautify her clients, a Vacu-bot that erroneously spits out dirt, and an Umbrella-bot that opens and closes at inopportune moments. The misfit robots band together with WALL•E to change the fate of the Axiom.

GO-4 is the Axiom’s first mate, who harbors a secret with the autopilot. A roving pneumatic capsule with a siren light for a head, he is dutiful to a fault.

JOHN and MARY are two of the humans living on the Axiom, where they have settled into a life of pampered luxury. The arrival of WALL•E jolts them from their daily routines and causes them to realize the existence of one another, and that there may be more to life than floating around on their high tech deck chairs. Pixar veteran/good luck charm John Ratzenberger lends his voice to the character of John, while actress/comedienne Kathy Najimy (“Sister Act,” “King of the Hill”) speaks for Mary.

SHELBY FORTHRIGHT is the personable and charming CEO of the Buy n Large corporation, the massive global entity that gained control of the universe with its product line of robots (including the WALL•E line) and luxury space cruisers (like the Axiom). The corporation’s promises of a great big beautiful tomorrow echo on through Forthright’s digital messages even though things haven’t turned out according to plan. Fred Willard (“Best in Show,” “Fernwood 2 Night”) appears in the film as the face of the company.

The Idea Becomes Reatily: Futuristic Tale of Robots, Romance and Galactic Adventure

The image of a lonely little robot – the last one on the planet – methodically going about his job picking up trash intrigued director/co-writer Andrew Stanton from the first time it came up over lunch with his colleagues back in 1994. It would be many years before he would find a unique story that could use this character to its full potential.

Stanton explains, “I became fascinated with the loneliness that this situation evoked and the immediate empathy that you had for this character. We spend most of our time on films trying to make our main characters likeable so that you want to follow them and root for them. I started thinking, `Well, where do I go with a character like this?’ And it didn’t take long to realize that the opposite of loneliness is love or being with somebody. I was immediately hooked and seduced by the idea of a machine falling in love with another machine.

And especially with the backdrop of a universe that has lost the understanding of the point of living. To me, that seemed so poetic. I loved the idea of humanity getting a second chance because of this one little guy who falls in love. I’m a hopeless romantic in cynic’s clothing. This movie gave me a chance to indulge in that romantic side a little more than I normally would in public.”

Jim Reardon — a veteran director and story supervisor on “The Simpsons,” who directed 35 episodes of the show and supervised story on nearly 150 episodes — came on board to be head of story for “WALL•E.” He ended up co-writing the screenplay for the film along with Stanton.

According to Reardon, “We started with the idea of making `WALL•E’ a comedy, but about a third of the way through, we realized that the film is a love story, too. WALL•E is an innocent and child-like little character who unintentionally ends up having a huge impact on the world. The story arc of the film is really about EVE. Her character undergoes the biggest change, and the film is as much about her as it is about him. She’s very sleek, techno-sexy, and very futuristic looking. He’s totally designed just to do his job, and is rusty, dirty and ugly. But we always thought that would make a great romantic adventure.”

Producer Jim Morris sums it up. “This film is a mix of genres. It’s a love story, it’s a science fiction film, it’s a comedy, it’s a romantic comedy.”

One of the great turning points for Stanton in creating the story for “WALL•E” was stumbling upon the idea of using the musical imagery and songs from the 1969 movie version of “Hello Dolly” to help him define WALL•E’s personality. In fact, it is WALL•E’s repeated viewings of an old videotape of that film (the only one in his collection) that have led to the glitch of his romantic feelings.

Stanton explains, “I had been searching for the right musical elements to go with the film, and stumbling upon `Hello Dolly’ was the best thing that could have ever happened. The song `Put on Your Sunday Clothes,” with it’s `Out There’ prologue, seemed to play so well with the themes of the film, and yet would normally not be the kind of music you’d expect to find in a film like ours. It’s a very naïve song really, and it’s sung in `Hello Dolly’ by two guys who don’t know anything about life. They want to go to the big city and they `won’t come home until we’ve kissed a girl.’ There’s such simple joy to it and it really worked for us. When I found `It Only Takes a Moment,’ it was like a godsend. That song became a huge tool for me to show WALL•E’s interest in what love is.”

It only takes a moment

For your eyes to meet and then

Your heart knows in a moment

You will never be alone again

I held her for an instant

But my arms felt sure and strong

It only takes a moment

To be loved a whole life long…

~ Excerpt: “It Only Takes A Moment,” Hello Dolly

Says producer Morris, “Holding hands is the thing that WALL•E’s wanted to do the entire movie cause it’s what he’s learned from watching `Hello Dolly,’ it’s the way you show affection in that movie.”

Adds Stanton, “And I realized `that’s right.’ That musical moment in the film showed these two people holding hands and I knew it was meant to be,” he says. “I’ve always felt, almost with a zealous passion, that animation can tell as many stories in different ways as any other medium, and it’s rarely been pushed outside of its comfort zone,” concludes Stanton. “I was so proud to have had something to do with the origin and creation of `Toy Story,’ because I felt that the tone of the movie, and the manner of its storytelling broke a lot of conventions that were in people’s minds. And I still feel like you can keep pushing those boundaries. Even before I knew this film was going to be called `WALL•E,’ I knew it was yet another step in pushing those boundaries out farther. I’m so proud that I got a chance to make it and that it matched my expectations.”

Co-producer Lindsey Collins observes, “Andrew’s films have an incredible emotional core to them that lays the foundation upon which the action adventure plays out. He writes stories that are so simple and identifiable. Even though the movie is out there in terms of its concept and scale, it feels very personal from him as a writer. He likes to write about small characters whose journey or struggle has an enormous impact. In `Finding Nemo,’ Marion went on a journey, and Dory unintentionally had this enormous impact on him, and he was changed as a result.

“In a similar way, WALL•E is this unintentional hero. He has the ability to impact humanity, and the ironic thing is that he is the most human thing left on Earth. This little robot actually teaches humanity how to be human again. It’s that twist and irony combined with real emotion that I think is going to resonate with audiences.”

Stretching The Limits of Animation

Pixar’s talented team of animators has tackled some seemingly impossible tasks for the films they’ve created, raising the bar for quality animation on every occasion. From toys to ants, fish to monsters, and superheroes to culinary rats, they’ve created memorable characters that have become icons the world over. For their latest assignment on “WALL•E,” new challenges were posed by a colorful cast of robot and human characters. With supervising animators Alan Barillaro and Steve Hunter in charge of the group (50 animators at the peak of production), and directing animator Angus MacLane adding his experience and talent, this film represents another triumph in the art of animation.

Jim Reardon, head of story for “WALL•E,” observes, “What we didn’t want to do on this film was draw human-looking robots with arms, legs, heads and eyes, and have them talk. We wanted to take objects that you normally wouldn’t associate with having humanlike characteristics and see what we could get out of them through design and animation.”

Stanton explains, “We wanted the audience to believe they were witnessing a machine that has come to life. The more they believe it’s a machine, the more appealing the story becomes.”

One of the biggest challenges facing the animators was the need to communicate emotions and actions clearly without being able to rely on traditional dialogue.

“We felt we could do it with non-traditional dialogue, maintaining the integrity of the character,” says Stanton. “In real life, when characters can’t speak – a baby, a pet – people tend to infer their own emotional beliefs onto them: `I think it’s sad,’ `she likes me’ – it’s very engaging for an audience.”

According to Ed Catmull, president of Walt Disney and Pixar Animation Studios, “In `WALL•E,’ the animators are really operating at the height of their craft to be able to convey emotions and complex thoughts with so few words. It’s more about being able to touch people through the animation.”

Stanton notes, “In the world of animation, pantomime is the thing that animators love best. It’s their bread and butter and they’re raised on it instinctually. John Lasseter realized this when he animated and directed his first short for Pixar, `Luxo Jr,’ featuring two lamp characters who express themselves entirely without dialogue. The desire to give life to an inanimate object is innate in animators. For the animators on `WALL•E,’ it was like taking the handcuffs off and letting them run free. They were able to let the visuals tell most of the story. They also discovered that it’s a lot more difficult to achieve all the things they needed to.

“I kept trying to make the animators put limitations on themselves because I wanted the construction of the machines and how they were engineered to be evident,” he adds. “The characters seem robotic because they don’t squash and stretch. It was a real brain tease for the animators to figure out how to get the same kind of ideas communicated and timed the way it would sell from a storytelling standpoint, and yet still feel like the machine was acting within the limitations of its design and construction. It was very challenging — and completely satisfying when somebody found the right approach and solution.”

To help prepare them for their assignment, the filmmakers and animation team met with people who designed real-life robots, visited NASA scientists at Jet Propulsion Laboratory, attended robotic conferences, and even brought in some real robots, including a bomb sniffing robot from the local police department. To understand what the human characters might look like after hundreds of years of pampered life in space, NASA expert Jim Hicks came in to discuss disuse atrophy and the effects of zero gravity on the body.

Jason Deamer, the film’s character art director, recalls one of the starting points in designing WALL•E was his eyes. “Andrew came in one day with the inspiration for WALL•E’s eyes. He had been to a baseball game and was using a pair of binoculars. He suddenly became aware that if he tilted them slightly, you got a very different look and feeling out of them. That became one of the key design elements for the main character.”

The rest of WALL•E’s design stemmed from functionality. “How does he get trash into himself and how does he compact it?” Deamer asks. Field trips were made to recycling plants to see trash compacting machines in action. “We knew he needed treads to go up and over heaps of trash,” he says. “He also needed to be able to compact cubes of trash, and have some kind of hands to gesticulate.”

Do Robots Have Elbows?

One of the big points of discussion in creating the character of WALL•E was whether or not he should have elbows.

“Early in the film, we had designed WALL•E with elbows,” explains supervising animator Steve Hunter. “This gave him the ability to bend his arms. As animators, we were fighting for it thinking he’s got to be able to touch his face, hang off a spaceship, and have a wide range of motion. But when you really looked at it, it didn’t feel right. He’s designed to do a task, which is to pull trash into his belly. Why would he have elbows? It didn’t make any sense. So with Andrew’s help and an inspired idea by directing animator Angus MacLane, we gave him a track around his side which allowed him to position his arms differently and give him a range of motion. It helped us flesh out the character a lot more. Something like elbows may seem kind of trivial but the way we solved the problem makes you believe in WALL•E more because we didn’t take the easy way out.”

Despite the relative simplicity of his movements, animating WALL•E proved to be one of the toughest assignments yet for the animation team. According to supervising animator Barillaro, “WALL•E has a lot of different controls including about 50 for the head alone. He’s not organic like a human. We had to boil his movements down to their bare essence to make them effective. The first thing the animators wanted to do when they got a scene with him was to do all their tricks like bouncing his head around. They were trying to get too broad and too human. We had to keep reminding them to pare things down and go as simply as possible with the animation. Simpler is definitely better in this case.”

With WALL•E’s voice being such an important part of his personality, the animators worked in close concert with sound designer Ben Burtt to inspire one another. Typically, the animators would work with the rough designs to prepare test animation. Burtt would then add WALL•E’s voice, and send it back to the animators for another pass. Voice and animation would get edited together, and out of that would come the final performance.

Animating EVE also posed its share of challenges for the group. With only two blinking eyes and four moving parts, she required a lot of advanced thought and just the right subtle movement. Designed to look like a futuristic robot, EVE is the epitome of elegance and simplicity.

“We wanted her to be graceful,” says Stanton. “There are different ways to convey what is masculine and what is feminine in this world and we felt that she should be fluid, seamless, she should have attractive feminine qualities.”

MacLane explains, “While WALL•E’s movements are more traditional with motors, gears and cogs, EVE is this sleek egg-shaped robot who moves through the use of magnets. Every frame and composition has to be cheated ever so slightly so that it’s pleasing to the eye. She has this gracefulness and elegance in the way she moves which you’d expect in a technically advanced robot.”

Hunter adds, “Every plane change, every angle, and even the way her head curved around to the back when rotated had to be posed in a certain way to make it feel right. Everything with her had to be really, really subtle. Basically, she consists of only four parts, and two eyes that blink. We had a lot of discussions about how she would move using her arms. We treated her almost like a drawing in some ways and came up with just the right poses to express emotion. It’s pretty amazing how much you really read into her.”

In addition to some of the other main robot characters – Auto, M-O, the reject bots, among others – the character design team created a catalogue of robots and crowds of up to 10,000 humans to populate the Axiom. A modular robot system was devised using a series of different robot heads that could be combined with a variety of arms and bodies. Painted various colors and otherwise differentiated, countless robots were created.

Co-producer Collins notes, “We created a library of characters with interchangeable parts so that we could do a build-a-bot program. We could choose from different kinds of treads and arms. You could swap them to create different silhouettes and characters. We had close to a hundred variations and about 25 different basic silhouettes that we could mix and match to make the world seem fuller.”

MacLane credits Stanton with inspiring the animators to do their best work. “What makes Andrew such a successful director,” says MacLane, “is his ability to see the film in its entirety at all times. He’s able to zero in on what you’re working on and suggest how to make it better for the sequence. His sense of story is so strong and he knows how to communicate that to the animators. He likened good storytelling to telling a joke. He’s ultimately trying to tell a really good joke over a period of nearly 90 minutes. We have all these building blocks that evoke emotions and he’s trying to figure out the best way to tell it. Our job in animation is to make sure we’re communicating clearly to the audience and that it supports his ideas for the story.”

Stanton sums up his appreciation for the animators on the film. “They were just such champions of this movie, and they really loved the concept, and particularly the challenges and the limitations that we had put upon ourselves for designing all the characters the way we did. They got it from the very beginning.”

What The Beep?

The cast of characters in “WALL•E” includes a wide assortment of robots, including several that speak or communicate in their own unique language. For the film’s producer Jim Morris, and director / co-writer Andrew Stanton, there was only one clear choice to create the specialty voices for these robot characters and design the sounds for this film. And that choice was multiple Oscar-winning sound designer Ben Burtt, the legendary talent who created the voice of R2-D2, the crack of Indiana Jones’ whip, the hiss for “Alien,” and many other iconic sounds known to moviegoers everywhere.

“Ben is one-of-a-kind,” says Stanton. “He is such a master of sound design, and he’s the name that’s been made famous by every kid who ever liked `Star Wars’ and all the films that followed.

“When I realized I was actually going to get the chance to make `WALL•E,’ I knew that in many ways the film had to rely on sound to tell the story,” Stanton continues. “I wanted our robots to communicate more on the level of R2-D2 than C-3PO – with their own machine-like language. I felt it would be more clever, more interesting that way. When Jim told me that he had worked with Ben at ILM for many years and suggested that we invite him over, I was thrilled. I pitched the movie to Ben and told him that I would need him to be a good deal of my cast. Thank goodness he said yes because it soon became obvious that we couldn’t have done it without him. He’s the absolute best.”

Jim Morris adds, “Ben’s ability to create other worldly voices and special voices that have emotion and sentiment made him a perfect casting choice for WALL•E and we’re so delighted that he worked on the film. Some of the character voices he created are completely synthetic, some are made up of a conglomeration of various types of sounds that Ben has found or created, and some of them are based on a little bit of human performance that is then manipulated. Ben was also extremely important with all the sounds in the movie.”

Burtt explains, “My background on `Star Wars’ gave me lots of experience in working with robot and alien voices, but `WALL•E’ required more sounds for the robot characters than any previous movie I’d worked on. The challenge of this film was to create character voices that the audience would believe are not human. Yet they could relate to the characters with all the intimacy, affection and identity that they’d attribute to a living human character. The voices couldn’t just sound like a machine with no personality, or like an actor behind a curtain imitating a robot. It was a weird balance between sounding like it was generated by a machine but still had the warmth and intelligence – I call it soul – that a human being has.”

Burtt got the call to work on “WALL•E” just months after completing work on the last “Star Wars” film. He had told his wife “no more robots,” but the temptation to work at Pixar on an entirely different kind of robot film proved to be too strong.

“Fortunately, it was such a fresh and exciting idea, and the challenge of the sound in the film really appealed to me,” says Burtt. “Sound and the robot voices were going to play such an unusual role that I couldn’t help but be inspired. So of course, I signed on to work with Jim and Andrew, and do the sound design for the film.”

Regarding the voice for the character of WALL•E, Burtt explains, “It starts with me in my little recording chamber in our sound department. I take those original recordings and run it through my computer in which the sound is analyzed and broken down into all its component parts. Much like you’d take light and run it through a prism to break it into a spectrum of colors, you can do the same thing with an audio file. Once you’ve broken the sound into all its component parts, you can start re-fabricating it back together again.

But now you can control the amounts of one thing or another. I can inject a machine-like quality into the sound, and do things to it that the human vocal chords could never really do. You can hold a certain vowel longer and stretch it. You can change the pitch of something up and down. You can put two sounds close together. In re-fabricating the sound with a particular program I developed, I was able to keep as much of the original performance as I wanted but add a bit of synthetic form to it.

“If sound were silly putty,” adds Burtt, “you could stretch it and make it longer. And I found a way of working on WALL•E’s voice where I could do that. It gave a quality that Andrew really liked, and it allowed us to keep the personality going.”

In addition to the character WALL•E, Burtt was also responsible for the voices of M-O, Auto and EVE, whose tone he created by manipulating the voice of Pixar employee Elissa Knight.

For the other sounds in the film, Burtt created a library of 2,400 files – the most he’s ever accumulated for any film. “WALL•E” was Burtt’s first animated feature. “Animation is very dense and the sounds are all really fast,” he observes. “When I was initially making sounds for WALL•E, I found I was always doing it too slow, so I had to speed up everything in my life to get the sounds fast.”

Burtt had to be resourceful in creating sounds for the film. To make the sound of the cockroach skittering, he found a pair of police handcuffs and recorded the clicking as he took them apart and reassembled them. To get the sound of EVE flying, he found someone who had built a 10-foot long radio controlled jet plane, and recorded it flying immediately overhead. Running up and down a carpeted hallway with a big heavy canvas bag created a howling wind effect that was perfect for an Earth wind storm. And a hand-cranked inertia starter from a 1930s biplane did the trick in creating the sound of WALL•E moving into high gear.

“The best part of working on any film when you’re the sound designer is when you’re alone in your editing room and you’ve got some finished footage in front of you,” says Burtt. “And you put the sound in for the first time, and something really clicks. You’re the first one to see it and that’s a sweet moment. Wandering the halls at Pixar was really inspiring because there are so many talented people there doing incredible things. I would go back to my studio and think, `can my sound be as good as what I’m seeing?’”

Out There: Fantastic Visions of Earth and Space

The production design for “WALL•E” required a unique cinematic vision of the future that ran the gamut — from an abandoned trash-covered Earth to an enormous floating cruise ship in space perched on the edge of a nebula that is home to thousands of humans. Overseeing the production design on the film was Ralph Eggleston (“Finding Nemo”), a Pixar veteran with art director credits on “Toy Story” and “The Incredibles,” and who directed the Oscar-winning short, “For the Birds.” Working closely with him to achieve his artistic goals were three top art directors: Anthony Christov (sets art director), Bert Berry (shading art director), and Jason Deamer (character art director).

According to producer Morris, “The biggest overall challenge on this film from my point of view was the production design and locking down the look of our sets and environments. We knew going into it that we needed to have a future incarnation of Earth in its abandoned state, but it was enormously complicated to get all the detailed nooks and crannies figured out. The design of the Axiom and the space environments were also tricky, but we had a larger body of material for those elements to research and learn from. Ralph and his team did an amazing job creating entertaining and intriguing worlds that became characters in their own right and helped Andrew tell the story he wanted to tell.”

“One of the great things about what Pixar does,” explains Eggleston, “is that we create animated films that also have elements of special effects films and live-action films. We find our own sense of world and create it from scratch. With `WALL•E,’ it was essential that the audience believe in this world or they would have a hard time believing that our main character is really the last robot on Earth. So we set out to make our Earth setting very realistic with a great level of detail. We created nearly six miles of cityscape so that everywhere WALL•E goes, we know exactly where it is and that world really exists. We ended up stylizing it quite a bit for animation, but these are the most realistic settings we’ve ever created here at Pixar. This was also our toughest assignment from an artistic standpoint.

“Another one of our goals on this film was to use color and lighting to highlight WALL•E’s emotions and help the audience connect with them,” he adds. “Act one is all about romantic and emotional lighting, and act two is very much about sterility, order and cleanliness. The second act is the direct antithesis of the first. As the film progresses, we slowly but surely introduce a little bit more romantic lighting. A big part of my job is wrangling all of these disparate ideas from the art department all the way through the production pipeline.”

For inspiration in creating the look of outer space for “WALL•E,” Eggleston and his team turned to idealized views of the future from NASA scientists of the 50s and 60s, and the concept art for Disneyland’s Tomorrowland.

“One of the biggest influences for me and everyone on the film in terms of creating our vision of the future was the art created for Tomorrowland,” explains Eggleston. “It wasn’t about the specifics, but rather the notion of `Where’s my jet pack?’ You look at a lot of the space program paintings of the 40s, 50s, and 60s, and you see fantastic imagery of buildings on Mars. Somewhere around 1978, they stopped doing that because they wouldn’t fund anything that they knew they couldn’t do. We were interested in showing what the future could be like and won’t it be great when we get there. That’s what we wanted to impart with a lot of the design of this film.”

Inspiration for the Axiom design came from researching luxury cruise ships, including those operated by Disney. Field trips to Vegas also helped to suggest practical lighting for an artificial luxury setting.

“The original concept for the Axiom came from a cruise line,” says Eggleston. “We designed a massive space ship that is as big as a city, several miles long, and capable of holding hundreds of thousands of residents. We knew that the audience would need some kind of visual grounding, so we put it next to a nebula. When we first see the nebula, it reminds you of a mountain with something on top, and then it reveals the Axiom.”

Advancing the Art of Computer Animation

“One of the things that Andrew wanted to do with `WALL•E’ was to create a different look than we’re used to seeing in animated films,” recalls producer Morris. “Very often animated films feel like they’re recorded in some kind of computer space. We wanted this film to feel like cinematographers with real cameras had gone to these places and filmed what we were seeing. We wanted it to have artifacts of photography and to seem real and much more gritty than animated films tend to be. During my many years working at ILM, I had met several people that I thought could be helpful with that.”

“Both Roger and Dennis spent periods of time on the film bringing their perspectives to it and giving us a lot of ideas about how things would look and feel,” says Morris. “We actually brought in some vintage 1970s Panavision cameras, similar to the ones used to shoot the original `Star Wars,’ and shot some imagery to get a sense of the kind of artifacts those lenses created. We observed technical things like chromatic aberration, barrel distortion and other imperfections, and took what we learned and applied it to our computer graphics photography. Dennis and Roger were pivotal in helping us get those looks. For example, their advice on cinematography, lighting, and composition helped us create the austere, glaring and harsh Earth landscape in the first act.”

Morris’ background in live-action and visual effects filmmaking also helped the filmmakers achieve their desire to have the movie feel like it was filmed and not recorded. “I explained to the technical team that in the real world, when you’re shooting, the lens is usually about three feet in front of the film plane and you’re getting perspective shift when you pan and tilt. They took this information and came back with imagery that looked fifty percent more like a photographed image. The result feels like there was a cameraman present, as opposed to being in some sort of virtual space where everything is pristine. There’s a bit of imperfection in the look of the final film that adds to its believability.

As director of photography for camera, Jeremy Lasky helped take the film to an even higher level. “We advanced our camera and lighting technology to give the film a feel like there was a camera and lens shooting the action. We used a widescreen aspect ratio and a very shallow depth of field to give a real richness to the cinematography. You’ll notice backgrounds out of focus, and more textured layers of focus in some shots to create almost watercolor compositions. We also used a lot of handheld and steady-cam shots, especially in space, to make the audience feel that could really happen, and that this is a real robot moving through a real world. You feel like you’re witnessing this scene really unfold. One of the great innovations for us on this film, and a first for Pixar, was that we were able to previsualize the key lights prior to shooting so that we would have a much better idea of what the final film frame would look like. In the past, we had no lighting information at all at this stage of the production.”

Danielle Feinberg was the director of photography for lighting. Acclaimed cinematographer Roger Deakins (“No Country for Old Men,” “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford”) and Oscar-winning visual effects legend Dennis Muren served as consultants.

“When I saw the finished film, I had one of those moments where I thought, `I’ve never seen a movie quite like this before!,’” concludes Morris. “I felt like I was seeing it through fresh eyes.”

Down to Earth Music: Thomas Newman & Peter Gabriel Create Cosmic Compositions

Andrew Stanton and composer Thomas Newman got along swimmingly on their first collaboration, “Finding Nemo,” so it seemed a natural that the two would come together for an encore on “WALL•E.” With its emphasis on visual storytelling and less dialogue, music plays an even greater role than usual in helping the filmmakers create moods and communicate their story. Newman collaborated with rock-and-roll legend Peter Gabriel on a song called “Down to Earth,” providing an entertaining musical epilogue to the film.

Stanton observes, “Working with Tom has always been a dream for me. I’ve been a fan of his music for a long time because he is such an original. I remember first telling him about this new project on the night of the Academy Awards in 2004 when we were there for `Nemo.’ I said that I have this idea for a film and it involves `Hello Dolly’ and science fiction. I was wondering if he would still speak to me after that. It turns out that the score for `Hello Dolly’ was composed by Tom’s legendary uncle, Lionel Newman, so in a sense, we were keeping it all in the family.”

“The one thing that’s guaranteed when you work with Tom is that you’re going to get something that isn’t conventional,” adds Stanton. “When you request something that comes from a conventional place, like a sci-fi genre, you know you’re going to get something with a slight left turn to it. His score always gives the film its own special stamp of identity and it doesn’t feel like anything you’ve ever heard before. For `WALL•E,’ he really found a whole new level of beauty and majesty and scale that was beyond anything I could have imagined.”

One of the things that Stanton most admired about Newman’s work on “WALL•E” was its ability to capture the big sweeping outer space themes as well as all of the intimacies of the relationship between the two lead robots.

“Tom was able to communicate a sense of the world we were creating with his score,” notes Stanton. “There’s a scene in the first act where we see WALL•E going about his daily routine and there’s a mechanical clockwork aspect to it. The score has a factory-like rhythm to it with almost a faint whistle, almost like whistling while you work. Tom is always able to find the truth of these moments. And with his unique style of overdubs and mixing after he’s recorded with the orchestra, he comes up with a fresh palette of sounds. He has a real natural ability to find the intimate emotion in a scene. I think that’s why we fit together so well, because my natural inclination is to emphasize the emotional aspect of storytelling.”

Newman adds, “Writing music for an animated film is very different than working in live-action. In animation, mood happens in smaller increments of time, seconds sometimes. Here’s a mood, and then `boom,’ an action takes place. I learned with `Nemo’ that you couldn’t just create a prevailing mood and let it sit very long. Working in animation requires making transitions, and it’s about how the music moves from one feeling to another.

“My music tends to be patterned or repeating, so I like to get together with a percussionist or a guitarist who can take these patterns and add to them to make them sonically interesting,” says Newman. “If you have repeating phrases oftentimes it allows the ear to hear colors that widen your perception of sound and music. What interests me about music is the depth of it.”

For the song “Down to Earth,” which is heard at the end of the film, Stanton had the opportunity to collaborate with another of his musical heroes – Peter Gabriel. A huge fan of the rock-and-roll legend since he was 12 years old, Stanton contacted Gabriel about writing a song that would be integral to the conclusion of the story.

Stanton recalls, “Working with Peter has been one of the biggest highlights of my professional career. When it came to the ending for our film, I knew that we needed to add some additional story points and create something with a global feel to it. And it suddenly dawned on me that Peter is the father of world music to much of the Western world. I got completely seduced with the idea of putting him and Tom in a room together and seeing what they could come up with. Tom went to London to jam with Peter and it was like this whirlwind romance. Suddenly, there was this amazing Thomas Newman/Peter Gabriel song called `Down to Earth,’ that is just beyond my wildest dreams. Peter’s lyrics are so deceivingly simple, but they’re spot-on. I was so moved when I heard the lyrics because they were so clever and fit so well. They felt completely indicative of Peter Gabriel, and knowing that it was based on the story I had written and that I had any association whatsoever with — it really blew my mind.”

“It feels very much like a Peter Gabriel song, but it has a connectivity and sensitivity that is Tom’s,” adds Stanton. “Tom was so inspired by the song that he went back into the movie and rescored some key moments to include some of the same themes. It really feels completely organic and integral to the film.”

Production notes provided by Walt Disney Pictures, Pixar.

WALL.E

Starring: Fred Willard, Jeff Garlin, Ben Burtt, John Ratzenberger, Kathy Najimy, Sigourney Weaver

Directed by: Andrew Stanton

Screenplay by: Andrew Stanton

Release Date: June 27th, 2008

MPAA Rating: G for general audience.

Studio: Walt Disney Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $223,704,223 (45.2%)

Foreign: $271,679,429 (54.8%)

Total: $495,383,652 (Worldwide)