Tagline: How can you find yourself, if no one can see you?

When Jasira’s mother exiles her to live with her strict Lebanese father in Houston, she quickly learns that her new neighbors find her and her father odd and exotic. Worse, her budding womanhood makes her traditional and hot-tempered father uncomfortable.

Lonely in this unfamiliar environment, Jasira seeks to connect with those around her and finds both comfort and cruelty. Discovering that her ethnicity and newfound sexuality make her a target, Jasira must confront racism and hypocrisy both at home and at school. Jasira is drawn to her Army reservist neighbor, Mr. Vuoso, who captivates her attention with his stacks of men’s magazines and confusing sweet talk. As she struggles to make sense of her raging hormones, she finds friendship and physical intimacy with an older schoolmate, Thomas. But even that relationship causes problems when her father discovers that Thomas is black.

Driven by a deep longing for affection and acceptance, Jasira becomes the embodiment of the racial, sexual and political agendas of these very different men in her life – her father with his old world ideas of women; her dangerously alluring neighbor, Mr. Vuoso, and Thomas, who offers the promise of some feeling of connection through sex.

When Melina, a concerned neighbor and expectant mother, tries to help her, Jasira’s explosive situation comes to a head. A harrowing look at the confusion and misguided exploration of youth in America’s track houses, public schools and suburban wastelands, Jasira wanders through this world and surprises herself by finding not only a gutsy resilience but a new sense of redemptive power.

From Alicia Erian, Author of the novel Towelhead

When Alan first called me to talk about adapting my book, he said, “I promise if you agree to this, I’ll make sure it stays funny.” I haven’t forgotten that because it was particularly important to me.

As Alan pointed out, without humor, an adaptation of the book could result in a maudlin abuse story. Though there are many things that delight me about the film version of Towelhead, the aspect that pleases me most is that he really kept his word. The material is dark, to be sure, but there’s plenty of dark humor to match. I think it’s incredible that Alan was able to take a novel’s worth of material and condense it without diminishing the impact of the story. When I first saw the film, I hardened myself a little, not wanting to feel bad about the inevitable edits. After a while, though, I stopped thinking about it. Alan’s sense of story is impeccable. His cuts were not only painless, but quite ingenious in parts. A couple of times, I felt like I actually learned something as a writer from what he left out.

When writers sell their books to be made into movies, it’s best that they detach from the process. I feel that I did an excellent job of this. The big surprise was that it was utterly unnecessary. I love what Alan did. My characters have remained my characters, only now even more so, having come to life.

Alicia Erian is the author of a collection of short stories, The Brutal Language of Love (Villard, 2001/Simon & Schuster 2008), and a novel, Towelhead (Simon & Schuster, 2005), a New York Times Notable Book. She lives in Boston.

Few stories have truly exposed what it’s like to be a girl in that moment of transformation from a child to budding womanhood in all its biological messiness and intoxicating moments of magic and terror – with such honesty and humor.

It’s this rare depiction of adolescence that brought Alicia Erian’s novel Towelhead to the fore. Erian managed to write about a young American girl of partial Middle Eastern descent struggling with the tricky problems of race and identity – amid the disquieting context of the first Gulf War – along with the intense experience of growing up in a fast-paced, hypersexualized world without any clear rules.

About the Production

When Ball began to think of doing a feature his agent sent him Towelhead. From the minute he cracked the unpublished manuscript, the story struck Ball as both startlingly truthful and cinematic.

“I read it over a weekend and fell in love with the world and the characters,” he recalls. “I found so many things about it compelling. It took me to so many places I didn’t expect. By turns, I thought it was horrifying, hilarious, touching, ugly and at the same time, wonderful and liberating. It was everything I look for in a story – I was drawn to the political aspects of the book and the humor of the book, which was so real and keenly observed.”

Then, there was the book’s unflinching, head-on look at the stark realities of teenage sexuality – both the thrill of discovering it in all its ecstasy and intoxicating influence and the danger of it being taken advantage of by adults who should know better. Ball was enamored with Erian’s spirited, multi-hued take on subject that is approached.

“Usually when you read a story about a young girl who undergoes any sort of sexual abuse or assault, the implication at the end is always that she’s damaged for life. But it’s such a statistically common experience for so many young women (and young men) that I found it truly refreshing that Jasira is not ruined by what she goes through, but that she comes out of the experience more powerful, with a healthy sense of who she is and with her own healthy sexuality very much intact,” Ball says. “In that way, her story is really revolutionary and quite inspiring. I loved the unashamed exploration of adolescent sexuality from so many different perspectives. Under tough circumstances – and in the face of all these men, from Mr. Vuoso to Rifat to Thomas, who each objectify her in their own ways – Jasira still begins to carve out her identity on her own terms.”

Macdissi offers, “The message is that we do have a choice. Jasira doesn’t surrender to self-pity. That is heroic, I think, and it’s done in a very non-sentimental way – it’s not mockish at all and that’s what was attractive about the book for me because she doesn’t fall into self-pity. Whereas with most movies we see characters like that we feel so sorry for them and I think TOWELHEAD describes the characters and the story in a way that’s very real. The more real it is, the more universal it is. A lot of people have gone through similar experiences and they came out strong. I don’t understand why, in movies sometimes, we see the opposite: is it to manipulate the audience? Because we do survive things. I’m a person who came from a war-torn country and I did survive. It was extremely traumatic, but we do survive and we do get better and we do learn and we do move on.”

After getting Erian’s blessing in early meetings that made it clear they were both on the same page, Ball began his adaptation, which is quite faithful to the novel’s dialogue and structure. Despite the fact that the story is told entirely from the very particular point of view a 13 year-old Arab-American girl – one Ball himself clearly has never experienced – he says that Erian’s prose was his primary guide.

“I felt like the point of view of the novel was so clear I kept as much of it as I could,” he explains. “Alicia captured so many perfect little moments that really show the narcissism of Jasira’s parents, the loneliness of being 13 and the self-loathing of Mr. Vuoso. As I wrote, I never thought of myself as a man writing from a 13 year-old girl’s point of view but rather, as a writer creating a screenplay from a story that truly evoked a 13 year-old girl’s point-of-view. I tried to honor that the whole way through.”

Like Erian before him, Ball refused to shy away from the often hard-to-handle nature of changing adolescent bodies, explaining he doesn’t really find such secretly commonplace things all that daring. “I mean how many movies do we see where people get beheaded or dismembered, and people are afraid of seeing a tampon?” he muses. “I believe we live in a culture that wants to unnecessarily sanitize sexuality and biology and I fought for the fact that we should see this stuff because it’s real.”

But when it came to handling Jasira’s sexual encounters, Ball tried to straddle a subtler, razor-thin line between being as brave and honest as Erian without dipping into the visually lurid. “For me, the biggest challenge in adapting the book was definitely finding the best ways to reveal a true sense of Jasira’s sexual awakening without attaching it to particular acts or body parts,” he notes.

This is where Ball diverged into his own creative flourishes on the story, forging Jasira’s developing view of sexuality in the form of brightly lit fantasies of giggling Playboy Bunnies romping with carefree abandon. “Her fantasies were inspired by this kind of innocent idea of a naked woman running around completely happy in her nakedness before she realizes all the complications of sex,” he explains. “In Jasira’s mind, there’s this kind of magical world where women are appreciated for being beautiful without real cost.”

He also worked to keep the scenes between Jasira and Mr. Vuoso palpably real and charged without becoming explicit. “I noted in the screenplay that we would be focusing on character’s faces during these scenes, because that was what I was really interested in – the emotions, rather than what might be going on with specific body parts,” he explains. “I always felt if those scenes were too explicit it would become about that and detract from the more important emotional weight of what’s going on.”

Eckhart attests to Ball’s sensitivity in handling these difficult scenes. “In fact, on the first page of the script was a director’s note about how he was going to deal with it – that he wasn’t going to show it, the camera was going to stay at a certain level. We certainly did talk about it individually and as a group, because whether or not Summer is 18, in the audience’s mind she’s 13. It was difficult during those days, but I would have to say, Summer is such a great actress and Alan was such a sensitive director, we really had no problems.”

Still, one of the more controversial elements that Ball wanted to keep at the core of the screenplay is Jasira’s confusing attraction to her handsome, at times even vulnerable, reservist neighbor Mr. Vuoso. Ball acknowledges that there’s nothing simple about it. “Jasira lives in this tough world where both her parents are raging narcissists – her mother competes with her and her father is terrified of the fact that she’s becoming a woman. So she doesn’t really learn any boundaries from her parents And then she finds herself in these situations with Mr. Vuoso that are exciting, that break up the monotony in her life, that make her feel good and become the only thing giving her any power in her life,” he observes. “Everybody needs to have a place in their life where they have some sense of power.”

For Eckhart, Mr. Vuoso represents excitement to Jasira. He explains, “He’s a man, he’s an adult, he has a family, he has a job. She wants to play at being an adult. He’s right next door and there’s an excitement level there, it’s forbidden. He provides an outlet to act out and I think that she likes the attention because she doesn’t get it at home. Mr. Vuoso allows her to express herself.” Eckhart continues, “Jasira’s relationship with her father is abusive, she desperately wants approval, love, to be a grown up, to feel that she’s a woman, that she’s sexually attractive and that she’s normal. I think that’s what she’s looking for the entire film.”

Ball definitely wanted to break through the lingering cinematic taboo that still bars the idea that girls under a certain age can and do experience sexual desire – even while acknowledging how tricky that desire can be. “We live in a culture that tends to ignore such things, but the reality is that young boys and girls do get aroused. And that’s only human. In our puritanical mindset, we usually take that out of the equation. But it’s such a common experience that, again, what I loved about the book is that it put this all out there in all of its messiness and I wanted the film to reflect that.”

Bishil concurs, “I don’t think Jasira has a sexual obsession, it’s healthy when she’s masturbating, and it is healthy when she’s reading Playboy and its healthy when she finds Mr. Vuoso attractive. What happens is that Mr. Vuoso is unhealthy and he takes advantage of her. Then it becomes a problem. It’s a problem how they deal with it. Jasira is not the problem.”

Complexity certainly underscores every aspect of Jasira’s relationship with Mr. Vuoso – but Ball still condemns him in no uncertain terms. “Is Jasira provocative? Yes. Does that mean she deserves what happens to her? Absolutely not, Vuoso is an adult and he fails her and himself and society when he crosses that line. He’s a very unhappy man who’s carrying around a lot of pain, but that’s no excuse. And Jasira might like the feeling of his attention but he should realize she’s not old enough to have the proper perspective to make that choice.”

Eckhart expounds on the relationship between Mr. Vuoso and Jasira. “You have to believe that his intentions are true. That he really is falling in love with this girl. And that he can’t help himself. In life, we all have our addictions, neuroses, attractions and our compulsions and I think he becomes obsessed with this girl. As an actor it would have been harder for me if he were completely heartless. But when Jasira and Mr. Vuoso go out to dinner, they are really having a date. He is really trying to discover and explore and to get into her heart and make her fall in love with him. He really visualizes having a relationship with this girl. She gives him a joy that he hasn’t had for 20 years.”

Bishil adds, “From Jasira’s perspective, I don’t think she ever thought of Mr. Vuoso as a bad man. She never got to the point where she was thinking about the assault as an assault. To her he hadn’t committed a crime or hurt her except for one brief moment – and yet she was still very much drawn to him.” She concludes, “Jasira has that bubble of romance. I remember thinking that Jasira thought Mr. Vuoso was going to carry her away in his truck and they were going to escape together somehow. That’s how I played it, like she was that naïve.”

For Bishil, there was also a personal connection to the material. She explains, “The story resonated with me. My father’s Saudi Arabian and he is also Indian. I was born here, but I lived on the island of Bahrain until I was about fourteen when I came back to the United States, so I very much know what it’s like to encounter prejudice.”

While war, bigotry and sexual aggression rage on around her, for Ball it always came back to the fact that it is Jasira who emerges at the end of the tale with a kind of incandescent strength. He summarizes: “This story might take place in territory we’ve seen before, but don’t think I’ve ever seen this story of a young girl’s awakening sexuality told in way that was so heroic. And that’s what I hoped to bring to the screen.”

For Ball, casting the role of Jasira was critical. “I knew from the very beginning it would all hang on this girl,” he admits. And so it was that he set out on an extensive quest to find a young woman who could handle the breadth of the role, who could viscerally grow on screen from the curiosity, fascination and need of a child to a maturing sense of how to handle the chaotic universe, sexual and otherwise, around her. “It’s a very tough role to cast because you need somebody who looks like they could be 13 but who is also adult enough to navigate the complexities of the role,” he explains. “I saw people from all over the world, from England, Australia and New York. But then Summer Bishil walked in and that was it.”

Bishil, who was 18 at the time the movie was shot, was born in California but grew up in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, returning to the United States in 2003, and beginning acting lessons soon after. There was little doubt that she had the essential beauty and screen presence for the role, but there was something even more vital that compelled Ball. “Summer is very, very smart and also absolutely fearless,” Ball notes. “It wasn’t that long ago that she was 13 herself and it was clear that she understood exactly what was going on in Jasira’s head – that she simply got it. She gave this role everything and we seriously lucked out.”

Bishil confesses, “I was afraid that I wouldn’t pull it off, that I wouldn’t look 13, that I wouldn’t sound 13. But I just kept thinking back to what I was like when I was 13, the mannerisms, the gestures that I would do and I changed my voice – I actually didn’t speak like I would speak in normal life – I brought it down four or five years. I concentrated on her body gestures, because at that age you know to stand up straight, you know to carry yourself – but she doesn’t – so I focused on that, just little things like that to make it more believable.” She adds, “When I read the script, I thought I had to play this character. I felt like I had to get it, that it would be one of my hugest disappointments in my acting career if I didn’t. I just connected to it.”

Circling around Bishil’s alternately bewildered and empowered Jasira are a series of characters that each seem to want and fear different qualities in her without seeing who she really is inside. Yet even her inappropriately flirtatious neighbor and neglectful parents are drawn as intricate, wounded human beings not entirely in control of their anger, insecurity and passions. “One of the things I loved about the novel is that nobody was just a flat-out villain,” remarks Ball. “So I wanted actors who were very comfortable in that sort of human, flawed space.”

Bishil concludes, “More than anything I just felt a connection to Jasira’s spirit. It wasn’t `she’s half-Arab and I’m half-Arab,’ I just felt a connection to her spirit and understood her quest for companionship because she’s lonely.”

Perhaps the hardest role of all to cast was that of Mr. Vuoso. Tense, bigoted, unfaithful and fueled by a kind of distant sadness, he is also a man who allows himself to sexually pursue a 13 year-old girl. Many actors were scared of the part, but the one person Alan Ball most envisioned in it said yes: Aaron Eckhart, the Golden Globe nominee who has never been afraid of portraying the darker side of male sexuality. Although Eckhart is well known for playing the ultimate misogynist ladies’ man in Neil LaBute’s IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, it was his role in ERIN BROCKOVICH as Julia Roberts’ kind-hearted biker boyfriend that made Ball think of him for Mr. Vuoso. “He’s so charming and such an intrinsically decent guy in that film,” he says, “you see that side of him that Jasira would be attracted to.”

The role would definitely push Eckhart into places where few people want to go. “It was very hard for Aaron because he found the character’s actions so reprehensible,” notes Ball. “And they are reprehensible, but Aaron is also a great actor who can look at a role like this and say `I want to find a way into this guy’s humanity’ and I think he really succeeded at that.”

Eckhart explains, “It was a little bit scary. I felt like Vuoso was a complicated character and that there was risk involved for Alan, for me, for the film. I felt like that what’s Alan and I really talked about: who this guy was, what he was doing, why he was doing it and where he was coming from. Vuoso is really miserable in his home life – he’s come up against a wall – and he’s revitalized by the love of this girl.”

He continues, “Mr. Vuoso is yearning for love. Obviously he’s mixed up – he’s being unfaithful in his mind and in his heart to his family. But in the end, he recognizes what he’s done and he feels guilt and shame and culpability. I think that shows that he isn’t just a sociopath or a psychopath, which is important to me as an actor and it was to Alan too. We tried to get that right – to show that Mr. Vuoso takes responsibility.”

To play Jasira’s clearly incompetent yet also quite human parents, Ball knew he would need two actors who could ride a very fine line. “The complicated thing about her parents is that they each view Jasira as a threat and an inconvenience to a certain extent and yet they both also love her,” explains Ball.

Again, it wasn’t an easy bill to fill. For Jasira’s father, Ball turned to an actor he had worked with before on “Six Feet Under” but in an entirely different sort of role: Peter Macdissi (THREE KINGS, BAD COMPANY). Despite being best known for portraying the free-spirited, grandiose art teacher Olivier Castro-Staal in “Six Feet Under,” Ball knew Macdissi had the subtle edginess to take on this challenging part. “Reading the book, I immediately saw Peter in the role. I knew he was Lebanese and I thought he could do something special with this character that often surprises us,” he says.

Indeed, Rifat is in no way the stereotypical idea of an Arab. He’s a Lebanese Christian, rather than a Muslim, and a decided opponent of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq – as likely to rail against Saddam as he is against the blindly anti-Arab sentiments of his neighbors. “In Rifat, there’s a broader picture of Arab-Americans than what we are used to seeing,” notes Ball. “And it was really interesting to me that Rifat is a racist himself – and that felt very true. I think a lot of Rifat’s anger, as well as his deep fear of Jasira gaining any power, comes from the fact that he really feels he has so little power himself. And from the fact he’s been the victim of racism in his own right.”

Macdissi elaborates, “I thought the film was very important because ethnic minorities are not represented enough in the media. Because it deals with racism, sexuality and people who do not fit the norm or who are not `mainstream’ and how they function in America – I think that is very important – especially that minorities play a very important role in America. Granted, the story is not about that – the story is more about the human condition. This person, with his daughter, could have been anything from French to Spanish to even white; it just happened that they were Lebanese.”

Macdissi’s portrait of Rifat was so true that when Alicia Erian visited the set, Ball noticed she got a little anxious around him. “I think he really reminded her of her own father,” he muses.

Though flawed, Macdissi asserts that Rifat has Jasira’s best interests at heart, explaining, “He truly loves his daughter – he wants the best for his daughter and he really does want her to go to the best schools. His fear for her and his love for her is what’s interesting about the character – even though he makes all the wrong choices and goes about things the wrong way – ultimately he does care for Jasira.”

But, he continues, “Rifat is so self-involved and narcissistic that he is not capable of taking care of anybody else but himself. He can’t handle Jasira’s sexuality – he can’t handle the fact that she’s a woman – he’s phobic about sexuality, especially when it comes to his daughter.”

Just as Jasira experiences abuse at the hands of Mr. Vuoso, she also experiences abuse from her father. The scenes in which Rifat abuses Jasira, like those between Mr. Vuoso and Jasira, had to be handled in a very sensitive manner. Macdissi explains, “I had to go to a special place to be able to bring up all of those feelings. The emotional part was very hard to make specific and make personal. What’s good about Alan is he lets the actor be, he trusts his cast members and he just lets them explore and come up with a lot of creative things. And Summer was very open – that’s one good thing about being a newcomer, is that you’re very open and very resilient and very flexible about what comes along, which made it very easy.”

Meanwhile, Maria Bello took on the role of Jasira’s immature and needy mother, Gail, who sees in Jasira both sexual competition and companionship. Bello has twice been nominated for a Golden Globe Award – for Best Supporting Actress as the cocktail waitress who helps William H. Macy turn his life around in THE COOLER and for Best Actress as the wife who discovers her husband isn’t the man she thinks he is in A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE – and Ball knew she had the acting chops to take on the role. “Maria is such a terrific actress and, most of all, she’s comfortable playing a character that’s very flawed,” he says.

Equally tough to cast was the role of Thomas, Jasira’s schoolyard boyfriend who is thrilled by Jasira’s response to his sexual advances. “A lot of guys didn’t want to play this role because, while Thomas is a sweet guy, ultimately he’s opportunistic when it comes to Jasira and at the beginning at least, just wants to get laid,” says Ball. It was in casting sessions that Ball discovered Eugene Jones, an award-winning playwright, spoken word artist, accomplished poet and actor fresh out of Performing Arts High School, where he majored in drama. “Thomas is so young and fueled by his hormones in such a way that he’s really thinking of himself and I think Eugene did a fantastic job of showing that while somehow still allowing us to see him as the essentially nice kid he is at heart,” comments Ball.

To play Melina, the neighbor who comes to Jasira’s rescue, Ball chose one of today’s most versatile and admired actresses: Toni Collette, who won an Academy Award nomination for her role as the grieving mother in THE SIXTH SENSE. Yet, Ball notes that even Melina isn’t all that gallant. “She’s a little flash of light in this dark world Jasira lives in, but she’s also self-righteous and bossy and she sort of drops the ball,” he says. “I always thought Toni was a great choice for her because she’s got such backbone and she’s so smart and so good at everything she does.”

On a tight schedule and budget, TOWELHEAD was shot largely on a cul-de-sac in Pomona which stood in quite nicely for the banal, cookie-cutter Houston suburb of tract houses and flagpoles in which Jasira finds herself. Indeed, things were so tight that the production designer James Chinlund used a single stage set to create both Rifat’s tidy home and Melina’s more laid-back home, switching out all the key details that fit with their completely divergent characters.

Ball worked closely with Chinlund and cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel to create the films look. “I wanted to capture the loneliness of the mundane and that kind of disconnected confusion of middle-class American existence,” Ball explains. “Mostly, I was trying to find a visual metaphor for Jasira being lost and ignored in this vast landscape of stuff. I also wanted to use a lot of natural light to emphasize the idea that everything that happens to Jasira happens in broad daylight. And I wanted to give each of the three houses where the story takes place a sense of what was important to the people inside. At the same time, I didn’t want anything to be so specific and overwhelming as to take away from the universal themes of the story.”

Production notes provided by Warner Independent Pictures.

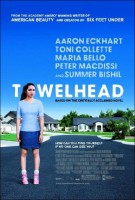

Towelhead

Starring: Aaron Eckhart, Toni Collette, Maria Bello, Peter Macdissi, Summer Bishil

Directed by: Alan Ball

Screenplay by: Alan Ball

Release: September 19th, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for strong disturbing sexual content and abuse involving a young teen, and for language.

Studio: Warner Independent

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $368,542 (93.0%)

Foreign: $27,683 (7.0%)

Total: $396,225 (Worldwide)