Tagline: What does it take to find a lost love?

After being arrested on suspicion of cheating on “Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?”, Jamal is released after telling about his incredible past. The Police Inspector releases him and when Jamal returns to answer the final question, the Inspector and millions of viewer watch. A penniless, eighteen year-old orphan from the slums of Mumbai, he’s one question away from winning a staggering 20 million rupees on India’s “Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?” But when the show breaks for the night, suddenly, he is arrested on suspicion of cheating. After all, how could an uneducated street kid possibly know so much?

Determined to get to the bottom of Jamal’s story, the jaded Police Inspector spends the night probing Jamal’s incredible past, from his riveting tales of the slums where he and his brother Salim survived by their wits to his hair-raising encounters with local gangs to his heartbreak over Latika, the unforgettable girl he loved and lost.

Each chapter of Jamal’s increasingly layered story reveals where he learned the answers to the show’s seemingly impossible quizzes. But one question remains a mystery: what is this young man with no apparent desire for riches really doing on the game show? When the new day dawns and Jamal returns to answer the final question, the Inspector and sixty million viewers are about to find out…

About The Production

The global adventure of making Slumdog Millionaire began with an unpublished manuscript from an obscure Indian writer: the debut novel of diplomat Vikas Swarup, Q and A, which traced the circuitous story of a young slum-dweller charged with foul play after winning a massive fortune on the nation’s most popular TV quiz show. The story’s mix-mastering of high comedy with deep poignancy, and its journey through a modern India teeming with equal parts human strife and human wonder, attracted the attention of executive producer Tessa Ross, the head of film and drama at Channel 4.

Seeing in the story an emotional power and distinctive cinematic potential, Ross in turn showed the manuscript to screenwriter Simon Beaufoy, best known for his Oscar nominated original screenplay for the runaway comic hit The Full Monty, which featured the equally unlikely scenario of six unemployed steelworkers forming an all-male strip act. Beaufoy was soon completely drawn in – first, by this new and different take on the classic rag-to-riches (or is it rags-to-rajah) fairytale, where our hero overcomes enormous obstacles to reach an uplifting conclusion; and second, to the extraordinary backdrop against which the story is set

He was especially excited because he believed that the story would reveal to Western cinemagoers a compelling side of India few have seen before, one of the heaving populous, massively diverse megacities growing throughout the world. “The book reveals Mumbai as a city in fast-forward,” he says. “It’s like a Dickensian London brought into the 21st century. It’s rapidly developing. The poor are poorer than ever before. The rich are richer than ever before. And there’s this mass of people in the middle, trying to force their way up. It’s a fantastic setting for a fairy tale.”

The challenge for Beaufoy was to retain the kaleidoscopic soul of the novel, but at the same time, translate its yearning, comical, romantic characters and disparate events into a tightly woven screenplay structure full of dynamic tension and creative interplay.

“The biggest problem in converting the book to a screenplay was that it was effectively a series of stories, twelve short stories,” Beaufoy explains, “some of which weren’t even linked in any way. It had no over-arching narrative. Some of the stories were almost discreet little tales that had no reference to the main characters at all.”

So Beaufoy meticulously picked his way through the novel’s many narratives and forged a through-line that would take the audience from beginning to end via Jamal’s tale-spinning at the behest of the Police Inspector. “My job was to find the overall narrative, to trace a storyline that went all the way through Jamal’s life, while still being able to jump back to the story of the police interrogation and the finale of `Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?’ It was quite a challenge.”

As Jamal flashes back on all the circumstances, some harrowing, others enlivening, that brought him to this moment of dire suspense on “Who Wants To Be a Millionaire?,” Beaufoy lets the screenplay jump fluidly across genres. “The fun part was that you could fire off in all different directions in this story,” says Beaufoy. “There are romantic bits, comedy bits, gangster bits – and I felt I was able to explore them all and still somehow encapsulate them all in a single tone, which was lovely for me. It gives the film a more dynamic feeling because it’s never stuck in just one genre.”

When the screenplay was completed, it was clear that Beaufoy had met the challenge of reshaping the novel into a rapid-fire tale of intrigue and enchantment that would inspire a director’s vision. Producer Christian Colson says: “Simon has a very warm, specific voice which is particularly well suited to this material. He was the one who came up with the new title of Slumdog Millionaire, which we all fell in love with. I guess in classical terms the script is a comedy – it’s a comedy but it also has pain and pathos. It’s a fairytale and like all the best fairytales, it has moments of real darkness and horror. It’s a story that will make you laugh, cry and often gasp.”

When it came to choosing a director for Slumdog Millionaire, the filmmakers knew the wide-ranging story of Jamal would require someone adept at merging the comedic, the adventurous and the deftly humanistic in one singular vision. Someone whose vision would have to traverse across themes of family, crime, survival and love in a story that is sometimes breathtakingly gritty and other times romantic and mythic. From the beginning, the team’s number one choice was Danny Boyle, who has shown an ability to sink his teeth into all kinds of iconoclastic stories of modern life, from the raw comedy of Trainspotting to the abject terror of 28 Days Later to his recent excursion into sci-fi, Sunshine.

“When we sat down and asked ourselves who would be the best person in the world to direct this material everyone thought `Danny Boyle!” Christian Colson recalls. “We sent it to him, he read it and said `count me in.’ It was that easy.”

On the one hand, Boyle seemed perfect for a story that squeezes an incredible breadth of storytelling into a rollicking entertainment. On the other hand, Boyle had never so much as visited India. This, however, turned out to be a positive.

Colson believes that that it was Boyle’s newcomer’s view of India that was able to bring such striking originality to the look and feel of the film, capturing at once the frenetic energy, ink-black comedy, gangster threats and hopefulness of Jamal’s life and circumstances. “Danny brings an outsider’s perspective to India in the same way that Sam Mendes brought his perspective to portraying suburban America in American Beauty and Ang Lee did to Jane Austen’s England in Sense and Sensibility,” says the producer. “Sometimes, a fresh eye can bring out the colorful, unique or vibrant that we, any of us, don’t see in our own cultures. I think there is a vibrancy to the movie that comes from Danny’s outsider curiosity. He looks at everything differently.”

Simon Beaufoy was further pleased by Boyle’s respect for the integrity of the script, as well as his ability to bring his own inimitable style and approach to the material. “Slumdog Millionaire is unmistakably a Danny Boyle film, with his absolutely unique vision, and yet pretty much every word that I wrote is there in the film,” says Beaufoy. “Danny was incredibly respectful of the words on the page and would never touch the dialogue without a huge amount of consultation with me as the writer.”

In turn, Boyle regarded Beaufoy’s script as a guiding light that continually inspired cast and crew throughout the filmmaking process. In the heat of shooting under very tough conditions, Boyle explains that it helped to remain as faithful as possible to Beaufoy’s blueprint. “I think the script is like a tunnel you get into and the fewer detours you make while you’re in it, the better,” he says. “As a director, your role is to make the movie as vivid as you can and as complex and exciting as you can, but always to serve the narrative as much as possible.”

With so much passion and creativity behind it, Slumdog Millionaire’s development path was unusually rapid. “It was like a snowball that grew as it rolled down the hill,” Tessa Ross comments. “Truly nothing stopped it in its tracks and things really speeded up because of Danny. We were able to develop and finance the film with Celador, and this meant we could then make all the important financial and creative decisions together very quickly.”

It wasn’t long before Boyle and his creative team were headed to one of the biggest, densest, most volatile yet vibrant cities on the planet. The next step was to find a cast who could bring the characters of Slumdog Millionaire to life with a raw naturalism befitting both their impoverished backgrounds and their infectious desire to grab the most they can out of life. The young performers in particular would help to create an eye-opening portrait of India’s slums as a place not just of lawlessness and corruption, but of heated dreams and daring, creative ways of getting ahead in spite of the staggering odds.

Boyle and Colson searched all over the US, Canada, the UK and India, and ultimately, they brought together a mix that spans from big-name Bollywood stars to non-pro discoveries from the streets of Mumbai. They were assisted in this epic process by Indian casting director, Loveleen Tandan, who would become a key element throughout the entire production. “Her role constantly expanded, from finding the kids to translating to them for me,” says Boyle, “guiding me through the finer cultural complexities of life on the street, and eventually directing the 2nd unit as it followed us around the city.”

The most vital task facing the filmmakers was finding a young man to play the adult version of Jamal – the young man who, orphaned by an act of violence, grows up on the streets as a lowly “slumdog,” works his way up to serving tea at an Indian call center, and ultimately turns out to be a phenomenon on “Who Wants To Be a Millionaire,” attracting a police investigation into his inexplicable trivia brilliance. The filmmaker knew they needed someone in the role who could be at once ordinary and heroic.

Extensive casting sessions were held across India, in Mumbai, Calcutta, Delhi and Chennai. But it didn’t prove easy. “The young guys in Mumbai, because of the culture, they tend to be really well built,” explains Boyle. “They are in the gym because that’s the look that’s expected. But I wanted a really ordinary guy, I didn’t want someone who looked like a hero.”

Finally, as the search dragged on, it was Boyle’s daughter who suggested the London-based actor Dev Patel, having seen him in his only other role to date in the UK cult television hit “Skins.” “Caitlin is a big fan of `Skins,’ and while I hadn’t really thought about Dev,” Boyle says, “as soon as she said that, I thought, yeah.”

He continues: “One of the things that was encouraging about him was that it pushed us towards casting the film very young. So, initially we were thinking of having the teens played by eighteen year olds and then in the final act of the film, when Jamal’s on the show, he’d be in his mid-twenties.

But I realized that was wrong. It’s important that what happens to them, happens to them at thirteen. That’s what’s so extreme and unacceptable and very Indian about it. So we wound up casting Jamal at seven, thirteen and eighteen – though what he sees in this short span of life is enough to fill a lifetime.”

Dev Patel became the only one who ended up being cast from London – most were cast in Mumbai — which only seemed to enhance his character. “We felt Dev had a wonderful fish out of water quality,” says Colson. “He’s immensely likeable and sympathetic. There’s a great innocence to the character of Jamal, a great optimism if you like. He’s someone who never loses his goodness, despite all the various evils that are perpetrated on him.”

For Patel, the lengthy auditioning process was excruciating. “I went home from my last audition nearly crying, in tears,” he recalls. “Then I remember my mum was at the bank and I was meeting her to do shopping and when I arrived she had tears in her eyes. I said, `Mum, what’s wrong?’ She said, `You wouldn’t believe who I’ve just had a call from.’ And she told me the news and we were ecstatic. I was literally shocked. I couldn’t believe it to be honest and I really wanted to get hold of Danny to check if it was legitimate or if someone was playing a trick on me.”

Being his first feature film role, and having grown up in Harrow in North West London, Patel was nervous about portraying a character born to a cutthroat life in the slums of Mumbai. He felt enormous pressure to get the accent – and the essence of Jamal’s hidden dreams. Arriving in India some time before his scenes were scheduled to shoot, he immersed himself in the vibrant, strife-filled atmosphere of the Mumbai streets to absorb the local mannerisms and tone, a revelatory experience in many ways for him. “Being a London kid, a British Asian, and having the chance to go to India and get in touch with those roots was really nice,” he says. “It’s like I found another piece of myself.”

Once the cameras began rolling, it became about turning all that he had absorbed into character. “I had to play emotional scenes and I had to play physical scenes and it really took it out of me,” Patel says. “But Danny always finds a way to get that right emotion out of you in a scene. He’s always encouraging you to try different things. He’ll do one take and once he’s satisfied, he’ll give you a new idea like, `imagine you feel this now’ or `this has happened to you’ so you play the scene from a totally different perspective and the story unfolds in a different way. I found the end product to be very three-dimensional.”

Patel’s favorite moments came when he had the chance to act with veteran stars Irrfan Khan (recently seen in Mira Nair’s The Namesake) as the Police Inspector and Saurabh Shukla (known for his comic roles as gangsters and criminals in such films as the cult classic Satya) as Sergeant Srinivas. “I learned so much from them because they are totally different actors. I was star struck at the start,” he confesses. “I had just watched The Namesake before Irrfan came on set and I was in awe because it was such a good performance. Saurabh kept on making me laugh on set. There is one scene where he is interrogating me and he’s slapping me on the face and beating me, and he still managed to make me laugh because he improvised lines and I was actually crying with pain but inside I was laughing.”

To play Jamal’s adult brother Salim, who takes a divergent path into a life of gangster violence and brutality, the filmmaker made a discovery: Madhur Mittal, a child actor from Agra, India, who became known in India after winning a dance-based reality television show. Then, a minor tragedy struck. A bike accident involving a rickshaw driver left Mittal with 12 stitches, an aggressive scar on his chin and the question of whether he was fit enough to take on the role. He convinced the filmmakers he was. “I think it actually helped me get into character,” he laughs. “Salim is supposed to be this tough guy, so it helped really.”

Mittal was attracted to the way Salim appears to be an entirely self-serving personality, but has a hidden compassionate side, and an abiding love for his brother, that only shows itself in the film’s suspenseful dénouement. “He’s a dream character for an actor to play, to be honest,” Mittal admits. “He’s a guy who everyone would love to hate but he obviously has this softer side to him as well, which he doesn’t want people to know, because he can’t have people seeing he is a tender person.”

He continues: “His relationship with Jamal is intriguing. They are complete opposites but still there is something that connects them. They irritate each other, because Jamal is too nice for Salim and Salim is too corrupt for Jamal, but they also love each other. They are brothers after all; they are born from the same mother and have the same blood running through their veins.”

The filmmakers set out on another extensive search for an actress to play Latika, the love of Jamal’s life, who drives his story from the first time he meets her as a desperate, brokenhearted street urchin in the pouring rain until the moment she unexpectedly reappears in his life. Simon Beaufoy notes that the adult actress had to be “someone you would crawl across the earth for.” The filmmakers found that quality in another fresh discovery: an Indian model and newcomer to acting, Freida Pinto, who Beaufoy says, “has got that extraordinary beauty alongside a strong sense of sadness about her, which we needed very much for her part in the film.”

For Pinto, who makes her film debut in Slumdog Millionaire, approaching the character of Latika was an exciting process. Having Boyle guide her through the scenes, offering advice and allowing her the freedom to try different approaches meant she quickly developed a solid understanding of where the character’s strengths come from. “Danny wanted me to explore the character as much as I could. Internalization is something that Danny really taught me,” she says. So intense were some of Pinto scenes, that during the sequence in which she is dragged into a car by gangster goons, a passer-by mistook her for someone who was genuinely in distress. “This guy came up to me and said, `Are you okay? Do you need any help?’ and I just looked at him and said, `We’re shooting,’” she recalls. “He said, `You scared the life out of me, you know.’ I was really happy because it was that convincing.”

Popular Bollywood star Anil Kapoor, who often plays the villain in Indian blockbusters, joined the cast in another key role: that of Prem, the flustered, egotistical host of “Who Wants To Be a Millionaire?” who, mystified by Jamal’s knowledge, calls the cops in on the cusp of his big win. It’s was Kapoor’s children who convinced him to take the role. “When I casually happened to mention Danny Boyle’s name in front of my children, they just sprang up and said, `Dad, that’s Danny Boyle! He’s made Trainspotting, The Beach. He’s a fantastic director. At least go and meet him.’”

Kapoor did and became fascinated by the character of Prem. “What’s interesting about Prem is that he is also from the slums, only he’s made it big and now his show is the number one show in India. He’s the producer of the show as well as the host, so he controls everything. Yet, even though he worked his way up from the street, he still doesn’t believe in any kind of morality. He wants to hold onto his power no matter what and Jamal seems like a threat to him.”

As one of India’s most prolific film actors, Kapoor was also intrigued to see how Boyle and his team would translate modern India – from steamy slums to lavish television studios — onto the screen. The results impressed him. “Danny got the feeling of India in a way I feel none of the films that have been made by foreign filmmakers have really been able to capture before,” he comments. “And the kinds of places where Danny has shot this film — I don’t think even Indian films have been shot in those kind of locations.”

Just as key as the adult cast to Slumdog Millionaire would be the younger cast, especially those playing the boyhood and teenaged Jamal, Salim and Latika.

Azharuddin Mohammed Ismail who plays the young Salim and Rubina Ali, who plays the young Latika, were both found in the slums of Mumbai and, knowing no English, speak in their native Hindi dialects in their wrenchingly realistic scenes. They have since been placed into education by the production. “We’ve managed to get them into school and hopefully they’ll stay in the school until they’re sixteen,” says Boyle.

To keep the characters consistent across different ages and settings, Boyle encouraged his entire cast to watch each other during rehearsals and even to try on each other’s roles, so as to keep them cross-referencing as much as possible. “The trick was getting people who could play each part but also add to the sense that they are all the same person,” he says. “We didn’t want to do a lot of it through make-up or prosthetics or anything like that. We wanted them to feel like they naturally grew out of each other. Once we’d got the eighteen year olds, we started to look back through the people that we’d auditioned to see who might resemble them in a way.”

“But of course, a lot of it, no matter what you do, is down to the audience and the momentum of the story,” Boyle notes. “You have to do it with a bit of style really, a bit of confidence — and I’m a great believer that the audience will go with that.”

But luck was also on Boyle’s side with the younger Jamals. “We discovered to our delight, that two of the `Jamals’ had big ears that stuck out. So you’ll notice there a lot of shots from behind their heads just so you think – `Look, it’s the same guy. He’s got the sticky out ears as well.’”

Tanay Hemant Chheda, who plays Jamal aged 13, recalls his first transformation into Jamal on set. “We had all come to the office and the make-up people were there to see us. I had really curly hair at that time while the other two Jamals had straight hair. I wondered how would I look like them? How could they match us? Then they were straightening my hair and after five minutes I looked up and there was smoke coming from my head. But the result of sitting in the make up van for one hour was really good. Chirag, the production assistant, always see me in make-up but when I was on set without it he didn’t recognize me and asked, `Are you Tanay’s brother?’”

“It’s a very difficult thing, having children, teenagers and adults all playing the same person,” summarizes Beaufoy. “The hair and make-up people did a lot of subtle work, pinning back ears and that kind of thing and worked with hairstyles, but it all comes down to performance. It’s a very tough trick to make work but I think we pulled it off.”

Shooting in The Maximum City

The story of Slumdog Millionaire unfolds in Mumbai (AKA Bombay), one of the densest, wildest, fasting moving cities in the world, rife with both danger and magic, dreams and despair, luxury and poverty — the city that author Suketu Mehta memorably dubbed the “maximum city” in his novel of the same name, a symbol of the vastly diverse megalopolises of the future in which the fates of rich and poor will be closely intertwined. With a population of over 19 million and rapidly growing, Mumbai is set to replace Tokyo as the world’s most populous city by 2020 according to estimates. It is already the world’s most crowded city, with some 30,000 people pressed into every square kilometer of space. And though it features luxury shopping, sun-soaked beaches and hip nightlife, it is also a city where as many of 50% of the citizens live in shantytowns, ghettoes or on the streets.

For Danny Boyle, the challenge was to capture the light and dark contrasts of the city with fresh eyes – creating a visceral, immediate experience for audiences, immersing them in its sweltering heat and teeming corridors. His plan was to shoot in the heart of the city’s infamous but rarely explored slums, capturing their energy and urgency on-the-fly, with an unforced realism. As a newcomer, his own emotional reactions to his first forays into the city became part and parcel of the film’s design. “I thought it was an extraordinary place in the extremes that you experience there. But also, the challenges that you face are just beyond anything you can imagine,” he adds.

Mumbai’s high-contrast mix of heartbreaking poverty and technological advancement especially fascinated Boyle. “I’ve been to slums before but in different places in the world, like Kibera in Kenya, but this was different in all its contradictions. There’s this smell you get first of all… this incredible mixture of excrement and then saffron, a mixture of the sweet and the sour,” he laughs. “India’s one of the world’s leading nuclear powers on the one hand, but on the other hand, there are no public toilets.”

All of these observations and sensations became part of the intensely textured fabric of the film. Says Simon Beaufoy: “I don’t think people living in Mumbai see Mumbai as extraordinary. But what Danny, Christian and I were able to bring to it, as outsiders, is an open mouthed sense of awe.”

Christian Colson notes that the production purposefully left the beaten path behind. “Some of the specific challenges we faced were of our own making, in as much as we elected to shoot the vast majority of this movie in real locations, on the streets of one of the most densely populated and chaotic cities on earth,” he says.

Mumbai itself dictated the pulsing rhythm of the film. Boyle has always been a director who cleverly manipulates the environment around him to create mood and atmosphere – but in India that kind of control just doesn’t exist, he notes. “If you seek it, it will drive you insane,” remarks Boyle. “You’ll be jumping off a cliff within a week. You’ve got to go with it really, and just see what happens. Some days you think, `We’re never going to get anything, not a single thing.’ And suddenly at four o’clock in the afternoon, it comes back to you. This place will repay you, if you trust it.”

The production agreed on a pre-shoot strategy that allowed them to begin filming around the city in advance of the agreed official start of shoot date. While the different departments prepared for the shoot, Boyle and a skeleton crew began filming rehearsals, in order to maximize the amount of shooting time they had in India. “It was a great way of just getting into making the film,” says Colson. “We essentially started filming two weeks early. Everyone was there. The equipment was there. We were on the ground near the location, so we actually started shooting.”

Boyle also felt that the film’s lead, Dev Patel, who stars as Jamal, would benefit from spending time in Mumbai before the cameras rolled and invited the young actor to come along on several location scouts. For Patel, the experience helped him better understand the character and where he came from.

“I really wanted to have a chance to play a scene when I was actually in the depths, in the slums, immersed in that environment,” says Patel. “Being on the locations really helped me to build a background for Jamal and see where he’d grown up. In one location Danny saw a few kids playing the drums on the street. They were preparing for the Ganesha Festival. Danny told me to turn my T-shirt inside out, because I had a big logo on it, and said, `Go and join them!’ I said, `What?!’ and he said, `Just go and join them.’ They got me in. They got someone to translate, put the drum on me and I started drumming. And Anthony, the DP, came in with a small DigiCam and just started filming it, without attracting too much attention to himself.”

The production shot in Dharavi, Mumbai’s so-called “mega-slum,” with its staggeringly diverse population of more than 1 million, an infamous mafia that controls everything from land to water, and a landscape forged from corrugated tin buildings, red asbestos roofs, mountainous garbage and non-stop human activity. They also shot in the city’s most vibrant shantytown, the Juhu slum, which is situated next to the airport and clearly visible to anyone flying into Mumbai. There, they plunged themselves and their cameras into the hubbub of everyday life and learned a lot about how this world operates with its own rules and underlying sense of honor.

“We put as many real slum-dwelling people in the film as we could get,” says Boyle. “The slums are actually thriving, bustling mini-metropolises. Now, in fact, what’s happened, because India is a democracy, is that the slums have become incredibly powerful places politically because they have a lot of people in them. There are a lot of votes in a small area. There’s a big plan to clear Dharavi at the moment but a lot of those who live there don’t want it cleared. They’re very suspicious of what they’ll be given in its place.”

He continues: “Because of the scarcity of land in Mumbai, they’ll probably be moved out to what’s called New Mumbai, New Bombay, which is miles away and where they don’t want to live. What’s important to them is not so much sophisticated dwellings, it’s actually community. It’s that they live together and they support and help each other. They have huge extended families of cousins and uncles. So it’s a real challenge for their politicians to try and find a way of updating the standards of living and yet retaining people’s demand for close communities.”

The task of shooting amidst the bustle of these ramshackle cities-within-the-city fell to award-winning director of photography Anthony Dod Mantle, who most recently shot the Oscar- winning Last King of Scotland, and has previously worked with Boyle shooting 28 Days Later and Millions. Mantle had to be extremely flexible in his shooting methods. The crew originally planned to shoot certain scenes using highly advanced SI-2K digital cameras and shoot the rest of the movie on film, but Boyle was adamant that he did not want to take large, cumbersome 35mm cameras into the slums. The smaller, more flexible digital cameras enabled them to shoot quickly with much less disturbance to the local communities.

For Boyle, it came down to trial and error to find the right shooting process. “We started off using classical kinds of film cameras and I didn’t like it. I wanted to feel really involved in the city. I didn’t want to be looking at it, examining it,” he explains. “I wanted to be thrown right into the chaos as much as possible. There’s a period of time between about 2am and 4am where it all stops and just the dogs move around, but other than that, the place is just a tide of humanity.”

The hyperkinetic chase sequence involving the young Jamal and Salim at the beginning of the film, in particular, was filmed incrementally, built up, like a montage over a period of time. Whenever possible, the crew would return to the location and film another section of the chase. “Anthony was able to hand hold the SI-2Ks,” recalls Boyle. “Although they had a gyro on them to stabilize them, they were still very small and could operate in very small, narrow areas, which is what you get in the slums. You can capture a bit of the life that’s going on around you, without people realizing it and becoming self-conscious.”

Boyle continues: “We also used what we called a `CanonCam,’ which was a Canon stills camera, which takes twelve frames a second. If people see a still camera, they don’t think it is recording live action. We’d record stuff like that, as well as occasionally using the traditional film camera – so it’s a mixture of different technologies that we used in the film. Whoever was operating the camera would have a hard drive strapped to their back, which would record the images while the camera was in their hand. Anthony would look like a rather cumbersome tourist from Denmark who was wandering around the slums,” laughs Boyle, “but actually what he was doing was filming.”

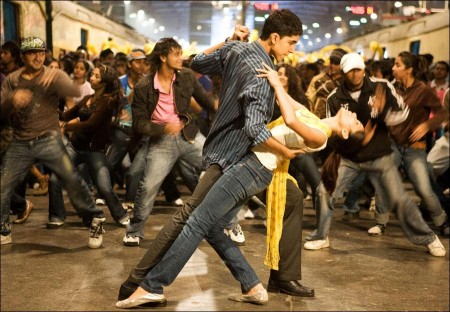

Other memorable locations included the historic 19th Century train station known as Victoria Terminus or VT (aka Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus), in the heart of Mumbai, where the crew also filmed the final dance sequence that runs over the end credits. Trains are a visual motif throughout the film. “The railways are the lifeblood of India, really,” explains Boyle. “There’s an extraordinary number of people killed each day on the railways: people hang off the trains because they are so packed. People live and work alongside the railway too. They have this amazing technique to dry their clothes. They put a stone on each corner and, as the train comes by, it blows hot wind underneath the clothes and they literally dry in five minutes. But it’s very dangerous. They’re so close to the trains as they speed past.”

One of the most difficult scenes to film was that of the young children jumping off a speeding train right outside the splendorous Taj Mahal, which they mistake for heaven. “That was very, very, tough. We had a very good stunt guy who dealt with this. The lives of the kids were absolutely in his hands. He did a brilliant job for us really, but it was tough,” comments Boyle.

Finding locations and being granted access was a logistical challenge for the location scouts and support from the team’s Indian connections was vital. A local production company, India Take One Productions, brought its knowledge to the production, enabling the team to very quickly map out how they would move swiftly from one location to the next. But distance is not necessarily the biggest issue in India. With millions of cars, rickshaws and taxis vying for the roads, traffic jams are as much a part of daily life as eating and sleeping – and must be accounted for in scheduling. “One of our challenges, unanticipated really, was that we’d look at the map before we went out and think `We’ll shoot this location, it’s only a couple of miles away’ – but it could take two hours to get there,” recalls Colson. “It was so congested. It’s like New York at its most manic.”

Overall, however, the support systems for filmmaking in Mumbai were far more advanced than the production had originally imagined. Although chaotic to a degree, Colson is clear to point out that facilities were available across all aspects of the production process. “Mumbai is a world center for filmmaking. The facilities are first class. There are fantastic crews, studio space, telecine houses. It’s all there,” he says.

But the fast-changing cityscapes around Mumbai were continuously challenging. Locations that had been sourced mere months before had, in many cases, changed so dramatically that alternative areas had to be found. Simon Beaufoy was amazed at how much the city’s look had altered since his early research visits. “I’d think, `Right, that is a fantastic location’ and six months later I’d go back with Danny and say, `Look at this fantastic… Oh! It’s gone.’ Here in the UK, we couldn’t get an escalator on the underground fixed in six months. And yet over there, they’ve built entire mega cities in that time. But we used all of this. We really wanted to get that sense of a city just burning itself up with energy, people, money, dust and dirt, and most of all, the movement of people.”

For Boyle and the rest of the team, this meant seamlessly merging the production as much as possible with the daily hustle-and-bustle of a city filled with constant suspense and a tangle of human stories – including Jamal’s astonishing journey towards a life he never could have imagined.

Sums up Colson: “The film’s a fairy tale and like all the best fairy tales, it’s got light and shade. So, one minute we were at the Taj Mahal, which is one of the most beautiful places you will ever see, and the next we were at some incredibly tough places. It was quite an odyssey for Danny and for all of us.”

Production notes provided by Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Slumdog Millionaire

Starring: Dev Patel, Freida Pinto, Madhur Mittal, Anil Kapoor, Irfan Khan, Tanay Hemant Cheda, Tanvi Ganesh Lonkar

Directed by: Danny Boyle

Screenplay by: Simon Beaufoy

Release: November 12, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for disturbing images, language, some violence.

Studio: Fox Searchlight Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $138,176,581 (47.5%)

Foreign: $152,920,507 (52.5%)

Total: $291,097,088 (Worldwide)