Tagline: How far you go to protect a secret?

A haunting love story based on the best-selling novel of the same name, “The Reader” is set in postwar Germany and tells the story of a man whose life has been shaped by an illicit affair with a passionate older woman during his youth.

Bernhard Schlink’s “The Reader” has been translated into 39 languages and has garnered numerous awards. “The Reader” was the first German novel to reach number one on The New York Times Bestseller List.

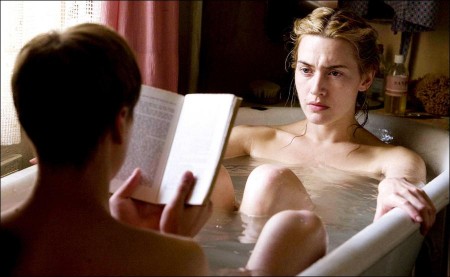

“The Reader” opens in post-WWII Germany when teenager Michael Berg becomes ill and is helped home by Hanna, a stranger twice his age. Michael recovers from scarlet fever and seeks out Hanna to thank her. The two are quickly drawn into a passionate but secretive affair. Michael discovers that Hanna loves being read to and their physical relationship deepens. Hanna is enthralled as Michael reads to her from “The Odyssey”, “Huck Finn”, and “The Lady with the Little Dog.” Despite their intense bond, Hanna mysteriously disappears one day and Michael is left confused and heartbroken.

Eight years later, while Michael is a law student observing the Nazi war crime trials, he is stunned to find Hanna back in his life – this time as a defendant in the courtroom. As Hanna’s past is revealed, Michael uncovers a deep secret that will impact both of their lives. “The Reader” is a haunting story about truth and reconciliation, about how one generation comes to terms with the crimes of another.

From Book to Film

The compelling story of The Reader in many ways touches on the deeply transformative power of words and literacy. So it seems fitting that the film originated with a lyrically simple, yet emotionally jarring, book—“a formally beautiful, disturbing and, finally, morally devastating novel,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

Written by Berlin law professor and mystery novelist Bernhard Schlink, the semi-autobiographical work was published in 1995, later translated into 40 other languages, and became the first German novel to top the New York Times’ bestseller list, garnering widespread attention in 1999 after Oprah Winfrey chose the title for her popular book club. “Who would have guessed that a book only 218 pages long could stir up so many emotions?” asked Winfrey, who noted that more men read the novel than any of her other book club selections before it was discussed on her program.

“It’s a story about what we call ‘the second generation,’” says Schlink, describing “the lucky late-born” children of the post-war years. “We grew up in a very naïve way until, at some point, we realized just what our parents and pastors and teachers had done. When you love someone who has been engaged in something awful, it can entangle you.” In Germany, the movement towards comprehending the war even required its own psychological term—vergangenheitsbewältigung, meaning “the struggle to come to terms with the past.” The novel is considered so important to understanding the country’s history that it has even been used as a textbook in German schools.

Film rights to The Reader were acquired by Harvey Weinstein and Miramax Films in 1996. At Weinstein’s urging Anthony Minghella and his production partner Sydney Pollack became involved, with Minghella intending to both pen the screenplay and direct. But stage dramatist Sir David Hare, later to become an Academy Award nominee for his screenwriting work on The Hours, also read the Schlink book and yearned to adapt it. Since Minghella had just swept the Academy Awards with The English Patient and was mulling over several more epic projects, Hare tried to cajole him into handing over writing chores on The Reader, but Minghella remained determined to develop the script himself.

Nearly a decade later, with no screenplay completed, Daldy—who studied German as a boy and had lived in Berlin—began asking Minghella about the possibility of directing The Reader. Realizing it would be some time before he himself could become so involved with the production, Minghella agreed to let Daldry direct, with the provisos that it become Daldry’s next project, and that he and Pollack would stay on board as producers. As far as getting a screenplay, Daldry naturally thought of Hare. “We did The Hours, and so this is the second complicated and hugely ambitious film we’ve made together,” says Hare. “We’re very deeply bonded, much like people who have been to war together – we know each other’s strengths and weaknesses.”

Diverging from Schlink’s novel, which unfolds chronologically in three distinct segments, the screenplay version of The Reader “jumps through time,” in Hare’s words, with a structure that transports the viewer into the main character’s life at several different junctures from the 1950s through the 1990s and back again. A highly accomplished playwright, director and author weary of obedience to tradition, Hare struggles to revolt in his original works and he envisioned an exciting, fresh approach to his adaptation, without resorting to those “dreary old voice-overs” which often accompany first-person narratives.

“When I go to the cinema, I’m bored stiff by films whose shape and character I can predict from the moment I enter the theater,” says Hare, who was determined to unchain The Reader from the binds of previous WWII-aftermath films that dealt with concentration camps, postwar anxieties, and individual complicity in crimes committed by the state. “I’m only interested in things that don’t belong to any genre,” he says, adding, “This is most certainly not what can be called ‘a Holocaust picture.’”

“There have been 252 films made about the Holocaust,” says Daldry, “and I hope there are at least as many more.” But The Reader is something else, he believes, calling it “an odd piece” that belies expectations. Bucking the trend of previous survivor stories, a character revealed late in the film who made it through the camps alive is portrayed as a pillar of moral and intellectual strength as opposed to a weakened victim.

While Hare, Daldry, Minghella and Pollack understood the value of cinematic innovation and experimentation, one aspect of the project never wavered—respect and honor for those victims of Nazi war crimes. There was an understanding among the principals that the term “forgiveness” would not be mentioned—the film, in fact, avoids vague notions of redemption or forgiveness but, instead, deals with the very real problem of how a new generation comes to terms with its tarnished past.

To this end, both the screenwriter and the director toured Germany with author Schlink to discuss post-war guilt and the contentious reactions his novel provoked. “The book is of huge historical significance in Germany,” says Daldry. “It is the singular novel addressing the problem of ‘How do we continue after what we have done?’”

“It attracted both the most extraordinary praise and the most violent attacks,” adds Hare. “Trying to explore and understand Nazi crimes is a dangerous and volatile business—you can unintentionally cross a line that you don’t wish to.”

Determined to explain “how the children of a criminal generation lived with the consequences” of their parents’ misdeeds, Daldry was uncompromising. “The film tackles war crimes head on,” says the director, careful not to depict concentration camp guards as horrific ogres or outré villains but, rather, as average workers and local neighbors. “It exposes ordinary people who commit these crimes—the banality of evil.”

Unlike many screenwriters whose input stops after they deliver the final draft of their script, Hare was again welcomed into the filmmaking process by Daldry, just as he was on THE HOURS.

“Stephen allows me to be a collaborator from the beginning of filming to the end of editing,” says the dramatist. “He won’t work with people who are not committed to collaboration at a profound level. In that sense, it’s more like working in theatre than film. He is the most thorough director I’ve ever worked with—nothing passes through the lens by chance.”

As for the original author, Schlink too participated in ways he might have never imagined—even appearing as an extra in an outdoor beer garden scene where ill-fated lovers Hanna and Michael have lunch during a bicycling holiday. It was there he saw Daldry’s obsessions with accuracy and honesty down to the smallest, slightest detail, whether it involved a period prop or a quick glimpse by one of the actors. “Stephen has a sensitivity for the most tiny, subtle things, and that’s something I greatly admire.”

Casting the Reader

From the start, novelist Schlink had imagined actress Kate Winslet for the pivotal role of Hanna Schmitz, the 36-year-old tram worker who has an illicit affair with a teenage boy and later is revealed to have been a concentration camp guard hiding yet another terrible secret. “Kate Winslet was always my first choice,” says Schlink. “She’s a sensuous, earthy woman, exactly like Hanna.”

Winslet explains “I’m a relatively slow reader, but I just could not put it down and finished it in one day,” she recalls. At the time, however, Winslet was only 27 and felt far too young to tackle the part. By the time director Daldry reached out to her in early 2007, however, she had matured enough to handle the physically demanding role, in which the character ages from a strong, sexual woman in her mid-thirties to a bedraggled matron in her late sixties.

Working with director Daldry was exhilarating for Winslet, who describes their “collaborative relationship” as “almost as if we’re from the same tribe.” Adds the actress, “He has this unstoppable energy, and such a profound love for the story. As well as a very clear idea of how he wants the story to be told, he’s very happy for others to share ideas and come up with what’s best for the scene.”

For the role of Michael Berg, the youngster whose life is forever changed by his relationship with Hanna, Daldry selected two actors to cover the character’s dramatic thirty-year story arc—relative newcomer David Kross and veteran Ralph Fiennes.

The Reader marks the third film for German actor Kross and his first-ever role in English, a language he perfected while making the movie. Daldry was determined to find a German youth for the role of Michael, and auditioned Kross repeatedly to make sure he was the right choice. Initially, Kross’ mother felt the acting job might interfere with her son’s schooling, but she agreed to let him take the part if his year-end grades were strong—he studied especially hard, passed his courses with near-perfect results, and eventually landed the role.

Kross worked as much as seven hours daily with dialect coach William Conacher not only to learn his character’s dialogue , but also how to read Horace in Latin, and Sappho in Greek, in addition to other literature he recites in the film. “The challenge to me as a dialect coach was how to help a German cast speak English in a way that the audience would believe they were speaking their own language, and then find a way to slot Kate Winslet and Ralph Fiennes into it,” recalls Conacher.

Because the storyline relies on depicting the sexual relationship between Hanna and Michael, the film’s entire shooting schedule was structured so that Kross—who was just 15 when first cast—turned 18 before any of the bedroom scenes were shot.

The disparity in years between middle-aged Hanna and young Michael was one of the most controversial aspects of the novel — yet the story would simply not work any other way. “Hanna and Michael are 36 and 15 respectively so that they are truly of two generations,” explains Daldry. “Any closer age difference would change that.”

Indeed, during her televised book club discussion of The Reader, Oprah Winfrey directly addressed the characters’ age difference and its importance to the story. “Horrible things happen to people in many books I read that I consider to be part of the literature landscape, but I don’t disown them or not embrace them because their stories are not comfortable for me,” Winfrey said. “You can love the book without loving the relationship. I’m not condoning the relationship… Why couldn’t the boy have been older? Well, it would have been a completely different story.”

Playing the older Michael Berg who, many years later, is still trying to come to terms with his boyhood affair, Fiennes was initially attracted to The Reader because of the way the script balanced complex emotional issues. “The questions it asks about blame, judgment, guilt, love, sexuality are all quite complicated, but in the end it’s a very humane story,” he says. “The mark of a good screenplay is often that it seems simple, but the simple scenes include huge things. The beauty of this screenplay is that, in sentences which seem like an ordinary conversation, the undercurrents are full of different meanings and layers.”

All three actors only rarely crossed paths, since Kross and Fiennes played the same character at different times, and Fiennes and Winslet share but a single scene together.

Winslet thought Kross was “perfect” for the role of the young man who matures before our eyes. “David is remarkably similar to Michael Berg—he’s a very serious person, incredibly professional and sensitive. He’s willing to try things and wants to learn and grow.” Fiennes also praised the actor who plays a younger version of his character. “We don’t quite look like each other, but I understand we may have similar qualities as actors, so I can see why Stephen put us together,” explains Fiennes. “He is very natural, intelligent and aware, with a gentle humor that seems to float just beneath the surface.”

Both of the actors relished their time with Winslet as well. “I didn’t know anything about her really,” admits Kross, who only saw the actress in Titanic before beginning The Reader. But “working with her was not good, it was great,” he says, noting that, like him, Winslet started acting when she was quite young. “She’s very down to earth and very experienced.” Agrees Fiennes, “Kate is a fantastic actress. All of her work is full and rich. She brings her intelligence to the set and she probes and asks questions. She’s magnificent.”

Cast in supporting roles and smaller parts vital to the production was a virtual who’s who of German acting talent—“one of the greatest ensembles of German actors in recent history,” says Daldry, proudly. American movies fans will likely recognize Bruno Ganz (Wings of Desire) in the role of Michael’s law professor, Rohl, as well as Mattias Habich (Nowhere in Africa, Downfall) as Michael’s father. Other top German actors in the film include Susanne Lothar as Michael’s mother, Karoline Herfurth as Michael’s university love, Alexandra Maria Lara as young Holocaust survivor Ilana, Volker Bruch as his fellow law student, and Burghart Klaussner as a war crimes judge. Also in the film are Martin Brambach, Marie Gruber, Margarita Broich, Carmen-Maja Antoni and Hannah Herzsprung.

Preparing for the Reader

While a few location scenes took place in New York, The Reader was primarily filmed in several German cities including Berlin, Gorlitz and Cologne, with some outdoor sequences shot in the countryside on the border between Germany and the Czech Republic. According to director Daldry, “the only way to make the film was to do it in Germany, with a German crew.”

Making up the rest of The Reader’s creative team was an array of acclaimed Academy Award-winning craftspeople including director of photography Chris Menges (The Mission and The Killing Fields), editor Claire Simpson (Platoon), costume designer Ann Roth (The English Patient) and production designer Brigitte Broch (Moulin Rouge).

For production designer Broch, working on the film awoke some long-dormant memories. A native German who moved to Mexico four decades ago, she considers herself part of the “second generation” who grew angry with their parents and their silence about what occurred during the war. Making The Reader forced her to face her own society in a way she’d never done before. “It’s actually the first time that I dared to personally confront myself with it and say, okay, enough with fear, enough with guilt, I have to face it,” she says. “It was hard emotionally, like diving into the depth and somehow coming out on the other side.”

The actors, too, found certain elements of the story extremely difficult to handle. “Usually I love doing preparation,” says Winslet. “It’s so important to have done your homework and then let it all go. But for Hanna I had to read so much literature and watch so many documentaries about the concentration camps that, at a certain point, I couldn’t take it any more. There are so many images I know will never leave me, no matter how hard I try.”

The process of aging her character over thirty years introduced Winslet to yet another aspect of filmmaking, made only a bit easier with the help of hair and makeup designer Ivana Primorac, a BAFTA nominee for her work on Sweeney Todd and Atonement. “To portray the older incarnation of Hanna, make-up and the prosthetic body work took four hours,” recalls Winslet, who wriggled into a latex body suit to portray her aging, flabby frame instead of using easier, but less effective, padding under her costumes. “My whole body language changed,” she says, noting that others seemed shocked by her appearance while she took it in stride. “I didn’t mind looking in the mirror and seeing myself as an old hag,” she says, with a laugh. “It gave extra dimension to the character.”

Fiennes explained his process of preparing for the role with director Daldry. “He was always asking questions, which is great,” recalls the actor. “What does Michael really think about Hanna? How do you condemn someone you’ve been intimate with? Is that intimacy still something you hold close to you? He kept those questions circulating which was crucial, because there isn’t really one answer. But even with all these questions, Stephen was firmly nurturing. He takes the time to let you discover a scene, and he has the confidence to allow for changes over the course of a day or even during the shooting of a scene. It’s a great way to work because it gives the actor freedom.”

Planning and plotting out his character’s back-story was a new experience for young actor David Kross. “It’s the first time I’ve learned to do background research for a role,” he says. “Stephen took me to the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and bought five bags of books for me to study. It was then I realized how little I really knew about the Third Reich.”

Daldry and his crew were helped enormously in their quest for realism by the Fritz Bauer Institute in Frankfurt, a major repository for material relating to Nazi war crimes. Researchers at the Institute, led by Werner Renz, provided the movie’s art department with photographs, transcripts and other background that proved invaluable for authenticating details of the war crime tribunal featured in the film.

Most of The Reader’s courtroom scenes were based on the Frankfurt Auschwitz trails held between 1963 until 1965, in which 22 mid- to low-level workers from the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp were prosecuted. In stark contract to the earlier, more infamous, Nuremberg Trials of top SS officers, Gestapo leaders and others, the Frankfurt hearings revealed the wider array of Holocaust enablers and enforcers.

In fact, many real life attorneys and retired magistrates from that era appeared in the film portraying lawyers and judges, including Thomas Borchardt, Thomas Paritschke, Burglinde Kinz, Stefan Weichbrodt and Kark Heinz Oplustiel. Other legal scholars, such as Auschwitz prosecutor Gerhard Wiese and Judge Gregor Herb, served as consultants.

Furthering their desire for authenticity, Kross and a small crew spent a full day and night filming a sequence at the Stutthof concentration camp in Poland, where Michael roams the grounds and imagines the horrors of decades past. “It was one of the most extraordinary days of my life,” says Daldry of the shoot, which also provided its share of logistical difficulties when he was forced to film around Jewish groups from Israel visiting the area that were taken aback by the German-speaking crew.

Even more challenging were those deeply intimate, emotional moments between Hanna and Kross’ character, which were filmed after a shooting break that coincided with his 18th birthday. “This film had my first sex scenes,” admits Kross, shyly. “Stephen gives very simple directions, which is very good for an actor. The hardest part was the preparation, studying the story, rehearsing with the other actors and talking about the emotions. Once we actually got to filming, it was fun.”

A Note About the Producers

During the making of The Reader in early 2008, both Anthony Minghella and Sydney Pollack passed away, Minghella in March at the age of 54 and Pollack just two months later at 73. “They were enormous pillars of strength,” says Daldry, adding “it was shattering for all of us who knew these extraordinary men that they would not live to see the finished film.” Yet, in many way, their individual spirits still helped to guide the production. “All the time, Stephen and I asked one another, ‘Would Sydney be happy that we’re doing this?’ or ‘Would Anthony like that?’,” recalls Hare about their posthumous presence on the set and in the editing room. “Our ambition with the film was to make something these two men would have been proud of.”

A Nation – and a Generation – Scarred by Guilt

Knowledge of the Holocaust is assumed to have been widespread among German population during WWII. The SS had approximately 900,000 members in 1943. The German national railways employed more than a million citizens, and many would have processed the lines of cattle-cars packed with Jews being transported across the land. Other German civil service organizations directly participated in maintaining the camps, and thousands more mid- and low-level bureaucrats must have been aware of what was transpiring.

As a law student says in The Reader, “There were thousands of camps… everyone knew.”

When the war ended in 1945, an Allied consensus concluded that all Germans shared blame not only for the war itself but also for Nazi atrocities. Statements made by the British and US governments, both before and immediately after Germany’s surrender, mandated the German nation as a whole was to be held responsible for the actions of the Nazi regime, often using terms including “collective guilt,” and “collective responsibility.”

Even President Harry S. Truman acknowledged how difficult it was to determine those in command from those less culpable, and from those who merely turned a blind eye. In a letter to one US Senator, he explained that all Germans might not be guilty for the war, but it would be difficult to single out for relief efforts those who had nothing to do with the Nazi regime’s crimes. “I cannot feel any great sympathy for those who caused the death of so many human beings by starvation, disease and outright murder, in addition to all the regular destruction and death of war,” he wrote.

Almost immediately after the war’s conclusion, a rapid process of “denazification” began, supervised by special German ministers with support of U.S. occupation forces. At the same time the Allies, through the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, began a massive propaganda campaign to instill a sense of collective responsibility among Germans.

Newspaper editorials and radio broadcasts were developed to make sure all Germans accepted blame for Nazi crimes. The campaign used posters with images of concentration camp victims and accompanying text declaring “You Are Guilty of This!” or “These Atrocities: Your Guilt!” From 1945 to 1952, a series of films about the concentration camps were also produced and screened for the German public including “Die Todesmuhlen” and “Welt im Film No. 5,” with the goal being to lead the “outlaw nation” back into civilized society and democracy.

The German Government’s Post-War Stance

Officially, the Allies praised Germany’s response to its war crimes. The Government of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany until 1990) offered official apologies for Germany’s role in the Holocaust. German leaders often expressed repentance, most notably in 1970 when former Chancellor Willy Brandt fell on his knees in front of a Holocaust memorial in the Warsaw Ghetto, known as the “Warschauer Kniefall.”

Germany has paid some reparations, including nearly $70 billion to the state of Israel and an additional $15 billion to Holocaust survivors who will continue to be compensated until 2015. The German government reached a settlement with companies that had used slave labor during the war, with the firms agreeing to pay $1.7 billion to victims. Germany also established a National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Berlin for looted property. Legislation outlaws the publication of infamous Nazi works like Mein Kampf and makes Holocaust denial a criminal offence, while symbols including the swastika and so-called “Hitler salute,” are illegal. Furthermore, the government even has Israel arrange the curriculum for Holocaust education in all German schools.

Germany’s treatment of war criminals and war crimes has also met with wide approval. The country helped track down war criminals for the Nuremberg Trials and opened many archives to researchers and investigators. In addition, Germany verified over 60,000 names of war criminals for the US Department of Justice to prevent them from entering the United States and provided similar information to Canada and the United Kingdom. (Of course, not all war criminals were brought to justice and many peacefully retired in other countries.)

Despite these efforts, however, Germany has also been criticized for not doing enough to compensate for its crimes. The German government never apologized for the invasions or took responsibility for the overall war. The emphasis for blame is often placed on individuals like Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party instead of the government itself, so no restitution has been made to any other national government by Germany. Even after German reunification in 1990, Germany rejected claims for reparations made by Britain and France, insisting the matter had been resolved. Furthermore, Germany has been criticized for waiting too long to seek out and return looted property, some of which is still missing and possibly hidden within the borders of the country. Germany has also had difficulty retrieving some stolen property because of a need to compensate the owners.

Finally, Germany refused to allow access for decades to the International Tracing Service’s Holocaust-related archives in the town of Bad Arolsen, citing privacy concerns and other issues. In May 2006, a 20-year effort by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum led to an announcement that millions of documents would finally be made available to historians and survivors.

But What of the Next Generation?

The Reader author Bernhard Schlink and his German contemporaries were in a unique position—they were wholly blameless for their parents’ crimes, yet they were born and raised under in the shadow of these great atrocities. How his generation, and indeed all generations after the Third Reich, comes to terms with the crimes of the Nazis, is what Schlink refers to as “the past which brands us and with which we must live.” And, as a law professor says in the film, “What we feel isn’t important—what’s only important is what we do.”

Screenwriter David Hare explains, “The Reader is best known German novel about the post-war years and the impact of the Nazis on the Germans themselves. Very little written about what happened to the succeeding generation dealt with the guilt of being born at a time when, through no fault of their own, they inherited this massive crime.”

Schlink adds, “We all condemned our parents to shame, even if the only charge we could bring was that after 1945 they had tolerated the perpetrators in their midst… The Nazi past was an issue even for children who couldn’t accuse their parents of anything, or who didn’t want to.”

Schlink chose to exorcise his demons on the page. He presents his readers with Hanna, and he underlines her crime so it can be both clearly defined and considerably damned, walking a fine tightrope between the two positions. He admits via Michael, “I wanted simultaneously to understand Hanna’s crime and to condemn it. But it was too terrible for that. When I tried to understand it, I had the feeling I was failing to condemn it as it must be condemned. When I condemned it as it must be condemned, there was no room for understanding … I wanted to pose myself both tasks — understanding and condemnation. But it was almost impossible to do both.”

The book itself was not without controversy itself. Says Hare, “You can’t write about post-war German guilt without it being hugely contentious.” First of all, Schlink put a perpetrator rather than a victim at the center of his story, which represented a huge departure in Holocaust literature. And his approach toward Hanna’s culpability became a frequent source of conflict, with the author frequently accused of revising or falsifying history to make his characters more acceptable. In the “Süddeutsche Zeitung,” Jeremy Adler accused Schlink of “cultural pornography” and claimed the novel simplifies history by allowing its readers to identify with the perpetrators.

Schlink has said he finds most criticism over Michael’s inability to fully condemn Hanna comes from those closer to his own age. Older generations that lived through those times are less critical, he says, regardless of how they actually experienced the war.

Hanna and Michael’s relationship enacts, in microcosm, the delicate balance between older and younger Germans in the postwar years: “… the pain I went through because of my love for Hanna was, in a way, the fate of my generation, a German fate,” Michael concludes in the novel.

Throughout the film, there are scenes of construction taking place in the background—during Hanna and Michael’s torrid affair, and even later when Ralph is a successful lawyer and Hanna has, physically at least, been long gone from his daily life. The country was struggling to rebuild, not just its homes and offices and structures, but also its national character.

Michael represents the New Germany, and Hanna the Old. That is why the difference between their ages is as large as it is—and why they need to be a complete generation apart. Hanna is apathetic about what has happened; Michael is angry and demands answers. “It doesn’t matter what I feel, it doesn’t matter what I think,” says Hanna in one of the film’s climactic scenes, still refusing to feel remorse for her past. “The dead are still dead.”

In the novel, Michael asks, “What should our second generation have done, what should it do with the knowledge of the horrors of the extermination of the Jews? We should not believe we can comprehend the incomprehensible, we may not compare the incomparable, we may not inquire because to make the horrors an object of inquiry is to make the horrors an object of discussion, even if the horrors themselves are not questioned, instead of accepting them as something in the face of which we can only fall silent in revulsion, shame and guilt. Should we only fall silent in revulsion, shame and guilt? To what purpose?”

Production notes provided by The Weinstein Company.

The Reader

Starring: Kate Winslet, Ralph Fiennes, Alexandra Maria Lara, Bruno Ganz, Linda Bassett, Karoline Herfurth, Susanne Lothar, David Kross

Directed by: Stephen Daldry

Screenplay by: David Hare

Release Date: December 10, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for some scenes of sexuality and nudity.

Studio: The Weinstein Company

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $33,175,852 (46.7%)

Foreign: $37,838,038 (53.3%)

Total: $71,013,890 (Worldwide)