Reporter Angela Vidal (Jennifer Carpenter) and her cameraman, Scott (Steve Harris), are doing a story on night-shift firemen for a reality-TV program. A late-night distress call takes them to a Los Angeles apartment building, where the police are investigating a report of horrific screams. The TV team and emergency workers find an old woman, who suddenly attacks with teeth bared. What’s more, Angela and company find that the building has been sealed by CDC workers. And then the attacks begin.

On March 11, 2008, with no explanation, authorities sealed off an apartment complex in Los Angeles. The residents were never seen again. No details. No witnesses. No evidence. Until now…

For a reality TV show about people who work while the rest of the world is asleep, reporter Angela Vidal (Jennifer Carpenter) and her cameraman, Scott (Steve Harris), are assigned to cover a night shift with a pair of firemen at a Los Angeles fire station. After an uneventful evening, a 911 distress call in the middle of the night takes them to a small apartment building downtown. Police officers are already on the scene in response to bloodcurdling screams coming from an apartment on the third floor. Having stumbled onto a breaking story, Angela and Scott are determined to get it all on tape.

Entering the apartment unit to investigate, they find an old woman in a nightgown, standing alone in the dark. She’s covered in blood, her breathing erratic and raspy. She seems sick. And when a policeman approaches to help her, she suddenly attacks…with her teeth. The group subdues the woman and tries to get help for the injured policeman. But when they attempt to leave the complex, they find that the CDC has quarantined the building. All exits are sealed and guarded by heavily armed men.

Telephone, internet, TV, and cell phone access have been cut-off, and officials won’t give any explanation to those locked inside. The apartment complex and its residents quickly descend into panic. Trying to make sense of what’s happening, the inhabitants are forced to look to each other for help. Then there’s another scream from above. In the atrium lobby where everyone is gathered, a body falls to the ground from the third floor. And the attacks begin again…

When the quarantine is finally lifted, the only evidence of what took place is the cameraman’s videotape. Watch the tape and see the horror of what happened to those under QUARANTINE.

Setting Up A Quarantine

“Quarantine” is an English-language word that immediately brings to mind other words, like “fear,” “disease,” and “isolation.” But the film Quarantine started its life in another language. Producer Sergio Ag?ero discovered the award-winning Spanish movie REC during a trip to Spain in January 2007 (the film won Goya Awards – Spain’s equivalent to the Oscars? – for Best Editing and Best New Actress). “I saw a promo reel the production company was using to pre-sell international rights,” Ag?ero says. The film wasn’t even finished yet, but “that early reel sent shivers up and down my spine.”

Given such a captivating – and terrifying – film premise, Ag?ero immediately saw the potential to make an English-language version. “While they were still finishing REC in Spain, I brought the project to Roy and Doug of Vertigo Entertainment here in the U.S.,” he says. Roy Lee and Doug Davidson had already brought English-language versions of foreign films to American audiences such as The Ring, The Grudge and The Departed, so Ag?ero felt Quarantine would be a natural fit for Vertigo.

When producer Lee first saw the REC promo and read the screenplay, he was thrilled. “You could tell there was something special about it,” he says. Soon after the Spanish film was completed, the partners got a print and screened it for Screen Gems, who was so enthusiastic they put the film on the fast-track. “This movie came together as fast as any movie I’ve worked on,” says Lee. “From the moment we actually saw the original movie to the moment principal photography on Quarantine started was less than three months.”

Brothers John and Drew Dowdle were brought on to adapt the script. The duo had recently written the documentary-style thriller The Poughkeepsie Tapes, with John also directing and Drew producing, and the producers felt they would have a great feel for what Quarantine needed to succeed. The brothers were invited to present their take on the film, and they jumped at the opportunity.

Director John Dowdle says, “Drew and I were up against much bigger directors for this job. But we figured there are two of us, so we could out-prepare anyone. We worked night and day doing everything we could think of to get this job.”

Their strategy paid off. “The Dowdle brothers won us over for their great enthusiasm for the material,” says Ag?ero. “They were able to articulate the American take, building on what was good in the Spanish script and giving it a bit more punch for American audiences.”

Most remakes have the advantage of having a blueprint – the finished film – to work from. Those adapting the project can see what works on the screen and where changes could be made to enhance the story or suspense. In the case of REC, “We actually adapted Quarantine before we had seen it,” says John Dowdle. “They weren’t even done editing their film. We saw their script and a trailer and we adapted from that.

“Doing a remake is an interesting process,” continues John. “In some ways more freeing, and in some ways more creatively confining. We were overjoyed with the original material – it’s so good – that we were very excited.”

“It was nice to have something of such high quality to work from,” adds Drew. “We wanted to stay very true to the original because it worked in so many ways. I think the impulse is to want to change things and try to make them better, and I think we had to resist that impulse in a lot of areas and not screw up what was good already. We were very pleased with the balance we found between staying true to the original and putting our signature on it.”

Producer Lee adds, “We actually gave them a lot of leeway in crafting the new script, but they followed the original because it was very effective and they didn’t want to totally reinvent it.”

The filmmakers did make a couple of changes to enhance the realistic elements of the new project. “The Spanish movie was a bit more supernatural,” Ag?ero explains. The Dowdles wanted to ground the premise with a bit more realism – which makes it all the more frightening. “For Quarantine,” says Ag?ero, “the filmmakers also play up the paranoia caused by the fact that the government, who we expect to come to our rescue, is the silent enemy here, keeping us in the dark and not telling us why.”

“We were very careful to make sure there’s nothing that happens in this movie that isn’t in the realm of possibility,” John Dowdle adds. “The ‘rooted-in-reality’ nature of the film differentiates it from many horror films.”

Ultimately, the filmmakers “were very pleased with the balance we found between staying true to the original and really putting our signature on it,” says Drew Dowdle.

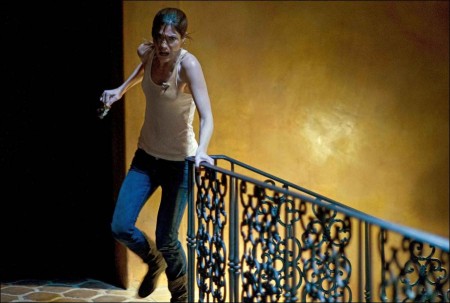

Because the central premise of the film dictates “found” footage from a single video camera used to record the action in the apartment building, the film takes place almost entirely in real time. Scenes meander in and out of apartments and up and down the central staircase, and they can last several minutes before the screen goes to black or whip-pans into the next scene. Transitions from scene to scene are largely made with hidden cuts.

“We’re seeing it all through the point of view of the camera,” says director Dowdle. “There’s something terrifying in a film when you can’t see around the door, you can’t see what’s on the other side of the wall. When you’re confined to only what one camera can see, you feel like you’re in a real space.”

“We loved toying with imperfect lighting and imperfect framing,” adds Drew, “not seeing everything you want to see and not hearing everything you want to hear. That imperfect nature makes it feel very real. And in today’s YouTube culture, everyone’s used to seeing everything recorded. Seeing everything from a one-camera perspective makes a lot of sense to audiences.”

The filmmakers also chose to shoot the film in script order, an idea often abandoned in modern filmmaking because of location, talent and time constraints. “We shot Quarantine in linear fashion,” says Lee. “The first scene we shot is the first scene in the script, and the last scene filmed was the last scene in the movie. It built tension as we were shooting.”

In addition to keeping the tension real and the action steadily intensified, John Dowdle found an emotional benefit to shooting in order. “When a character dies, that actor was wrapped,” he says. “There was a certain finality to their screen deaths, because when they died we really lost them.”

The filmmakers also found that shooting in order allowed them the freedom to experiment on set without adverse consequences. “Our experiments would often change the appearance of the actors or the reality of the situation they were in,” says John. “If we shot out of order, everything would have had to be decided ahead of time instead of in the moment. Drew and I felt very strongly that we needed to honor the moment as we shot this. You just can’t do that if you pen yourself in.”

Falling Under Quarantine

Casting Quarantine was no small task: the filmmakers had to find actors who could appear convincingly terrified while having the stamina to maintain that fear (an exhausting emotion to play) throughout a grueling real-time film shoot. Every frame had to feel immediate. The movie would only work if the actors were able to convince audiences that what they were seeing was real – and horrifying.

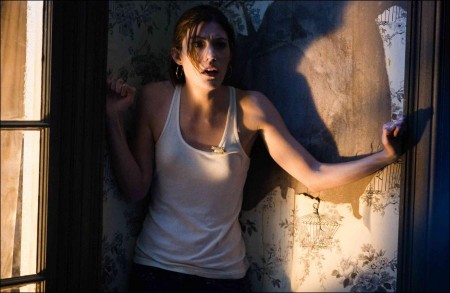

Most especially, the casting of the main character, Angela Vidal, was key to the film’s success. The role calls for a solid arc. Audiences meet Angela as a perky, rookie reporter for a local television show, just beginning her career. As she goes through the Quarantine ordeal, Angela morphs from an optimist to a determined and brave then ultimately terrorized woman facing her own mortality.

Of casting Jennifer Carpenter, Ag?ero says, “[Screen Gems President] Clint Culpepper had worked with her in The Exorcism of Emily Rose, and we all knew her from Dexter and were very intrigued by her as a strong, attractive young woman.”

John Dowdle says, “Drew and I had gotten into Dexter and we loved Emily Rose, too, but we didn’t realize it was the same person. Once we realized that, we knew she would be amazing.”

Discussing Quarantine, Carpenter says, “The thing that turned me on about it is the idea that we’re this group of people, mostly strangers, trapped in a building, fighting for our lives. Safety is just through that windowpane. It’s just a couple of floors down, it’s just through that door – salvation is an arm’s length away. Keeping that interesting throughout the whole film, plus the idea that my main scene partner was going to be a camera, I thought that was pretty intriguing…

“I don’t see a lot of horror films,” she continues. “It takes a certain kind of stomach. But this movie is so unique in how it’s put together. The script was sent to me along with a DVD of the original film, and I watched five minutes of it then made a call and said, ‘I want to do this. How do we make this happen?’ It was a really ambitious script and an ambitious idea of how they were going to make it.”

Carpenter says it was difficult to portray such relentless fear. “The script asks you to go at 100 miles an hour from start to finish,” she says. “It’s important to maintain that fear, that idea you have 30 minutes, 20 minutes, maybe six minutes to live. It’s been exhausting.”

To keep up her intensity, Carpenter says she used different “silly tricks.” “Sometimes it’s playing music that gets me going,” she says, “or it’s screaming before a take, or giving myself a second to really let everything be real and settle in. Sometimes it’s as simple as saying ‘one, two, three – GO!’ and seeing what happens. But it was a challenge to keep up that pace, keep it authentic and rooted in something real.”

Discussing her work in the film, John Dowdle says, “Jennifer’s just amazing. She stays in the zone all day long and really brings to much to every take. She comes up with wonderful ideas and is so wildly talented. There’s nothing she can’t do.”

Drew Dowdle adds, “Jennifer is exceptional. She feels real on every single teak. She’s been a great leader for our cast, we got really lucky to have someone who can bat a thousand like she has.”

Given the effort put into the piece, Carpenter is thrilled with how the film turned out. “I think it’s one of those films you have to watch over and over. Audiences are going to be like, ‘How did they do that?’ That’s the fun part. If someone asked me what to expect from the film, I would ask them what they themselves expect, knowing what they know about the movie from the trailer or the Internet or friends – then I’d tell them it’s even better.”

As Angela’s constantly-there partner, Steve Harris plays TV news cameraman Scott, who is only seen onscreen a handful of times but whose voice we hear throughout the film. Harris is well known for his role on the David E. Kelley hit series The Practice.

“It’s fascinating to do a film where you’re predominately a voice,” says Harris. “I wanted to play the cameraman the first time I read the script, when I actually thought they were going to shoot it like a regular film.” When they told him he wouldn’t be on camera as much as anticipated, “I even got more geeked about doing the film,” he says.

Director Dowdle says, “We initially talked to Steve about doing a role in which he’d be on camera a lot. But he came in to meet with us and said he wanted to play the role of the cameraman. He saw something in the character nobody else had.”

Harris saw his character not just as the guy holding the camera, but as Angela’s partner and protector. Harris says, “He does try to keep Angela out of harm’s way. He’s really working hard at keeping her – as well as himself – alive.”

The actor was also attracted to the “not-outside-the-realm-of-possibility” element of the premise. “That’s what really gets me about this,” he says. “It’s based on something that could really happen.”

Jay Hernandez and Johnathon Schaech were brought in to play Jake and Fletcher, respectively, the L.A. firefighters Angela and Scott are following for the night. In working with Hernandez, Schaech says, “We sat down and started preparing our camaraderie, which is such a big part of it, and our characters and how they would play each of the scenes. It was great.”

John Dowdle was impressed with Schaech’s interest and research into his role. “He’s so charismatic – he’s a scene-stealer,” he says. “He drove along with the fire department to really get into the role. And he grew the biggest, craziest moustache I’ve ever seen,” the director laughs.

Explaining his choice, Schaech says, “I spent time with firemen, and what I noticed is a great deal of the firemen have very thick, very masculine moustaches. So I took it upon myself – I grew it in four days.”

For his role, rising star Hernandez didn’t have to do as much research – the actor logged plenty of experience with firefighters while working on Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center. In describing why he feels the film is so effective, he echoes Harris’ based-in-reality sentiments: “For me, anytime something is going to be scary it has to be based in reality. When you can make somebody feel that this is possible, not just in the movie world but in their world, the fear comes home.”

Hernandez is also pleased with how the film was shot, and the effect the final result has on audiences. “They should expect to feel like they’ve been quarantined, that they’ve been trapped in a building,” he says. “You’ll feel as an audience member that you’re there. You’ll experience the range of emotion, the fear, the excitement, because you’re being put in that place. You’ll really feel affected emotionally by it.”

Among the residents of the doomed apartment building, Ally McBeal’s Greg Germann plays Lawrence, a veterinarian who’s called upon to adapt his medical skills to help the film’s victims. “I become the resident MD. Having worked on dogs and cats, somehow I’m qualified,” Germann laughs. His part called for his having to inject people with needles. “That’s partly why I got the job,” he continues. “I’m very good with needles.”

Germann was captivated by the project immediately upon reading the script. “I haven’t done a horror movie before,” he says. “It’s not really my genre. But this script was like a thriller – it’s a page-turner. It was really fun to read because every page, every moment is full of action. Things happen right away and continue to happen until the end.”

Also among the residents, Marin Hinkle plays concerned mom Kathy. In the film, her husband stepped out before the quarantine madness began and she’s now trapped in the apartment building with her daughter, who’s sick…and getting sicker. The actress was excited to show a different side of her acting skills. “I work on a sitcom, which is obviously a place of levity and a kind of goofiness,” Hinkle says. “I got a call from my agent asking me, ‘How would you feel about a horror film?’ I have a thing about horror films, but I read this one and there’s such a sense of reality to it, like it’s happening in the moment, so I thought it was intriguing.”

Hinkle’s audition story for Quarantine is quite memorable, for both humorous and heinous reasons. “I have a young kid,” she says, “and in the film I have a young kid, so that kind of connection was right there. But I hadn’t thought what I was going to do about having a child in the audition. So I used my purse – my purse became my child. In the film there’s a torturous scene where my child is being separated from me, so in the audition my purse and I were being separated. So I separated myself and went back and ended up slamming myself against the back wall. I’m screaming and I’m yelling, and it’s a Meryl Streep moment like in Sophie’s Choice. I finished and thought, ‘Wow, that was really real.’ That night I went to bed and about five hours later woke up with the most severe pain I’ve ever had in my life, even more pain than giving birth. Turns out that the crazy audition scene had loosened a kidney stone that was passing.” The resulting pain was the most excruciating of her life. Continues Hinkle, “If you ever want to be in a horror film, all you have to do is think ‘Kidney stone passing,’ and it gives you insight into how hard you can scream.”

In discussing the film, Hinkle says she’s pleased that the filmmakers were also able to find a little bit of humor in the horror. “It’s extraordinary that there’s a bit of comedy to it,” she says. “There’s this juxtaposition – the most severe moments of life are happening, you can’t go any deeper with the horror, so you have to go to a place where there’s a joke that comes out. It’s what happens in real life. My dad, when he had a heart attack and a stroke, he kept calling the hospital the ‘hotel.’ He’s like, ‘This hotel is really nice,’ and I was like, ‘Dad, I think this is a hospital.’ Chekhov has laughter in the middle of sorrow – pain brings that, and I think that’s one of the things that drew me to the script.”

The Apartment Building

For REC, the Spanish film crew shot on location using an actual apartment complex. Quarantine’s filmmakers at first thought they would do the same and utilize a practical location – they were looking at the famous Bradbury Building in Los Angeles. But they would have only had access to the building at night. And aside from the difficulty of a night shoot, the script called for apartment interiors to be linked in single shots with the main staircase. They would have had to cheat each shot, re-dress each office into an apartment every day, or rent offices for the duration of the shoot. Ultimately, it made much more sense to build their own set. A three-story apartment building was erected on Stage 23 on the Sony Pictures lot. At a massive 15,000 square feet and rising thirty-five feet high, the stage provided the perfect location and afforded the filmmakers the opportunity to build the set to the specifications of the script.

“The set was a really tricky build,” says Drew Dowdle. “There were so many bits we wanted to get into the film that were dependent on the set itself, and they were able to incorporate an incredible amount of the script and action into the design.”

“Production designer Gary Steele and his team did a terrific job designing the apartment complex,” says Ag?ero. “It was very elaborate, very detailed, and it involved a number of little small apartments around a central staircase and atrium. It enabled the director to shoot these very long takes, up and down the steps and in and out of apartments in a very organic and convincing manner. It also made our lives easier – we were able to work reasonable hours in very controlled conditions.”

All told, the three-story set (with a fourth floor going into the “perms” of the stage) boasted six bedrooms and three full units with a living room and dining room. The 4,800 square foot building took advantage of “dead space” (doors that led to nowhere) to conceal a permanent video village on the set itself, as well as departmental work and storage areas. The whole thing took six weeks to build with a daily average of 40 crewmembers. The structure itself hung on steel beams and cross beams, and production even had it’s own ironworks factory on the floor for structural and decorative creations.

A Different Kind of Shoot

Because of the premise of the film is that audiences are watching footage from one cameraman’s video camera, it was advantageous to shoot on HD. Says producer Lee, “We chose HD because we were able to manipulate it later to look like news and reality footage, and that’s one of the things that was very important for us.”

The filmmakers decided on the Sony F-23 camera. Director of photography Ken Seng says the F-23 had distinct advantages: “We could run takes as long as we wanted, go over and over and over again, and give it that news camera/documentary look while still maintaining a sense of style about how the film is shot.”

There was one downside: “It’s a fifty-pound camera,” says Seng. Lending to the film’s reality look, the footage was shot entirely handheld, which proved…heavy. “Once you put the deck on the camera, the operator was basically running up- and downstairs with a seventy-pound rig. It looks amazing, but it was a challenge.

“Everybody on this movie said it was unlike any other movie they’ve worked on because it’s so technical,” continues Seng. “Every single shot was so difficult to get. Sometimes there were ten takes of these five-minute sequences throughout the building. There would be thirteen actors, the camera operator, a focus puller, a stunt coordinator – all of us would have to totally be on point to make a take work, so it was really exciting when you’d see these sequences go off. While we were running through a room, we’d whip pan 180 degrees. Sometimes my cable wrangler would be running full speed and do a slide to get underneath the camera in the middle of takes. The dolly grip had cuts on his face and bruises on his shoulders. Everyone had fake blood all over them. It’s been a really physical show for the camera crew.”

It was also sometimes physical for the camera itself. Like the time “[camera operator] Columbus went running and caught the cable, and this $300,000 camera just goes flying through the air in seemingly slow motion and smacks on the terra cotta tile ground,” says Seng. “I think it’s a testament to that camera that we basically picked it up and shot with it right away.”

“With the frenzied pace of the film, and with the camera being in the middle of the action and treating the camera like a character, we realized part of making it all feel real was banging into the camera, letting characters slam into it or pushing it out of the way or grabbing onto it,” says director Dowdle. “A couple of times we had to take a little time to glue the camera back together and get it working again.”

Of the difficulty in shooting, John Dowdle says, “We had a camera shooting fifteen actors, sometimes with stunts, with effects, with all sorts of things – many days were spent just getting one shot. A five-minute scene done in one take took a lot of rehearsing, a lot of blocking. Many days we didn’t start shooting until the end of the day, and then we’d shoot, shoot, shoot. We didn’t have typical film coverage like you would in a normal film. You couldn’t hide a lot of stuff in editing. You had to get it on set.”

The same was true for the film’s impressive stunt work. There’s a lot of it, but it all had to be seamlessly integrated into those same one-shot takes. “The stunts couldn’t be broken away and shot separately like they normally are,” says John Dowdle. “They had to be incorporated into the organic whole. People would be acting, then suddenly there’s a stunt and people had to keep acting.”

“Throwing children on pavement, throwing people over railings – it’s a very different kind of scale for us, and it’s wonderful,” laughs Drew.

Lighting proved difficult as well. “For every single shot we were lighting for the wide shot, the medium shot, the close-up, and the reverse,” says Seng, “because we’d have to get all angles at once. We used all these little tiny LED fixtures and small lamps and Kenos, creating this base ambient level of light everywhere so that it doesn’t really feel lit. I was trying to use practical lamps as much as possible. It looks very raw and gritty and really works well for the story.”

All this precise lighting called for hours and hours of set-up. But, Drew Dowdle says, “The cast has been very patient with us.”

Cast member Jay Hernandez says, “It’s challenging because you had to get so many things right all at the same time. It’s like making music, all the instruments have to play together and it has to happen perfectly at least once.”

“It’s really a challenging and exciting way to work, because it depends on everybody pulling their weight,” agrees Germann. “If one guy messes up, you’ve got to do the whole take over again. It’s been really gratifying, really fun to do that.”

“You’ve really got to be in the moment,” says Johnathon Schaech. “You’ve got to really know where you’re coming from as the character. That’s why I studied so hard with the firemen and read as much as I could about what I needed to do in each of the situations.”

Columbus Short, who plays policeman Wilensky, agrees that the film really called for an actor to be on his game. “This movie is more of an actor’s piece because it’s like theatre,” he says. “It’s one take, and long takes, and the actors are constantly challenging one another, improvisational-wise. I love it. It’s a treat to work like this. You get to play. It’s an actor’s dream.”

The improvisational style and the use of one camera could feel strange, though. There was no coverage, no getting different takes of each actor’s performance to use later in editing. When her husband asked what it means to have no coverage, Hinkle laughed, “It means you’re not quite sure you’re going to be in the film in the end. You might be behind the camera acting your heart out, providing background, but in the end you go, ‘Hmm, I don’t think I was ever in front of that camera [in that scene].’ You’re acting in an incredibly truthful way, and the ego has to be removed from the process.” It was also exciting, she says, because “the accidents may end up being the most delicious parts of the film.”

Jennifer Carpenter sums it up: “One thing John said to us when we started is ‘If we catch you acting, we’re going to have to start over.’ I think it’s going to look really easy. It’s not going to be easy to watch, by any means, but it’s going to look like it was put together effortlessly, and I think that’s just a credit to how hard it’s been to make it.”

For their part, when asked what they’d tell an audience member to expect, the brothers Dowdle agree: “It’s relentless. You’d have to expect this film to break your mind.”

Production notes provided by Sony ScreenGems.

Quarantine

Starring: Jennifer Carpenter, Jay Hernandez, Columbus Short, Greg Germann, Steve Harris, Dania Ramirez, Rade Sherbedgia, Jonathon Schaech

Directed by: John Dowdle

Screenplay by: John and Drew Dowdle

Release Date: October 17, 2008

MPAA Rating: R for for bloody violent and disturbing content, terror and language.

Studio: ScreenGems (Sony)

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $31,691,811 (76.8%)

Foreign: $9,598,084 (23.2%)

Total: $41,289,895 (Worldwide)