Tagline: She’s stealing his heart. He’s paying for it.

Irène (Audrey Tautou) loves nice things and loves to have wealthy men pay for them. One night, she mistakes Jean (Gad Elmaleh), a poor bartender, for a potential client and spends the night with him. The next morning, Irène realizes her mistake and leaves, but poor Jean is smitten with her. Later, when a rich dowager mistakes Jean for a veteran gigolo, Irène agrees to tutor him in the art of fleecing wealthy lovers.

Jean (Gad Elmaleh), a shy young bartender, is mistaken for a millionaire by a beautiful, scheming opportunist named Irene (Audrey Tautou). When Irene discovers his true identity, she abandons him, only to find that a love-struck Jean has no intention of letting her get away. Jean’s comical attempts to gain her affections gradually evolve into setting himself up as a gigolo at a luxury hotel, until Irene finally starts to warm to her persistent, persuasive suitor. Against the wildly atmospheric backdrop of the south of France, Pierre Salvadori (Apres Vous) directs this sexy and thoroughly charming romantic comedy, which is a fresh re-imagining of the cinema classic, Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

What was the starting point for PRICELESS?

I was face-to-face with Benoit Graffin, my scriptwriter, and we told each other that we should make another movie. We agreed that it must be a comedy, one more…

Why?

I don’t know. The only time I’ve done something else (Les Marchands De Sable), it was ten times shorter and ten times less painful. I direct comedies, it’s my affliction! I have this obsession, to succeed with a light and fluid comedy. The first movie that ever struck me was a comedy – Heaven Can Wait (1943) which, for me, was watching the perfect movie.

And yet, the characters in the movie suffered, loved and were betrayed while others disappeared. Living in it was not easy, but the characters had grit in their pain, as did the production. Even before the true moral of the film was apparent, Ernst Lubitsch, through his choices and the way he shot, already had a point of view of the world. Choosing to make a comedy, with its maladjusted but combative characters, its subversive potential and its vitality, is also expressing a point of view.

And the story for PRICELESS?

The story came later. We were talking about what worried us, what made us anxious: the triumph of pragmatism over everything, the surrounding pessimism which can, at any moment, tilt us toward cynicism and lead us to finally say – – in order to win a place in the sun – – all means are acceptable.

First came Irène, a character fixated by an idea about happiness, who somewhat mixes up luxury. Then, came Jean, bewildered and shy to the point of submission. And, finally, the idea of the comical misunderstanding of their encounter.

Is PRICELESS a comedy about class struggles?

I say it with humor, but it’s true: Madeleine and Jacques’ behavior towards Jean and Irène, respectively, is very violent. These are people who control others. When Gilles leaves Irène, he takes back everything he gave her. When Jacques leaves her, he cuts her credit card in half. Irène and Jean have an arrangement, but don’t own each other. When they end up falling in love, they rarely see each other. Their time is not their own. This relationship goes through some very funny and difficult scenes, like when Madeleine throws pillows at Jean to wake him up. But, in the end, Madeleine will never control Jean…

He is “priceless”!

What we should all be. But, that does not include anxiety, the fear of not belonging to something and of being left aside.

Is it love that saves Jean and Irène?

No. Benoit and I wanted to avoid this somewhat illusive solution, which is typically found in many sentimental comedies. Love is often suggested as the only outlet when faced with the pressures of the world. For us, love was not the principal stake: they are in bed together within the first ten minutes and Irène falls in love long before the end of the movie. But, for her, love is a problem, not a solution! It weakens her, frightens her, confuses her. In the story, every time Irène falls in love, she pays the price: men leave her, humiliate her, they make her pay for it. Irène has planned her life and her career, and love, with all the sacrifices and gratuitousness which that may require, has no part in it. No, what saves Irène is jealousy. It is an irrepressible feeling. We wanted her to fight her love to the end and then let her be saved by an impulse. It’s animal like. But, maybe we need to rely on what is left in us that is animal like in order to remain human.

Jean never judges her.

It’s very important. He never preaches to her. He realizes very quickly that she lives in a world in which her way of earning money seems natural. Instead of judging her, he becomes just like her. He attacks from inside. He does not become her enemy, he becomes her ally. He marries her as if one were to marry a form. His virtue is that he does not renounce her. In his persistence – in what is said, is the harshness of what one can become.

She is very cruel!

She is tough. She wants her piece of the cake and she has no particular talents except her ability to seduce. It’s a talent that matches any other talent. Irène is a determined soldier and Jean is an enemy in the sense that he touches her. As soon as she realizes that she has tender feelings, that she is weakening and that he is putting her in danger, like any good soldier, she decides to eliminate him, to make him disappear: she ruins him so that he’ll finally go back home. And, Jean lets her do it. He offers himself to her and offers her everything, until he no longer has anything. It is a true economic suicide and an act of total love. And then, from a dramatic point of view, it’s interesting that a character can be tough. A comedy needs cruelty.

The way she looks at him evolves imperceptibly. One of the key moments of this evolution is the look Irène gives Jean, when she wakes up, on the beach…

That is the moment when she accepts and understands that she loves him. The viewer, who foresaw this, is, from now on, certain of it.

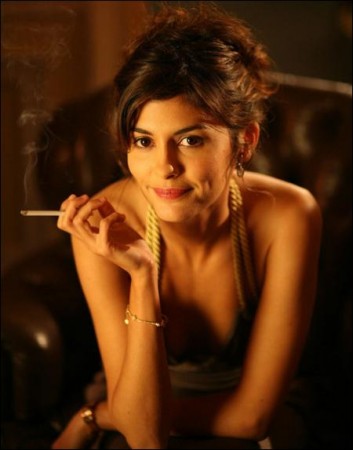

Irène could be defined by the look she gives… Audrey Tautou is capable of changing very quickly from one feeling to another in the same scene…

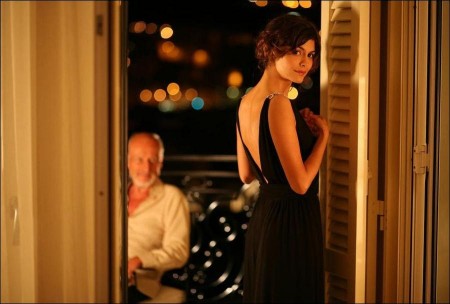

She was so good at it that I kept asking her for more! The scene that impressed me the most is when she is on the balcony with Jacques, at the end of the film. Irène is supposed to be totally available to this guy and at the same time, she cannot stop looking at the one she really loves, behind him. To play it this way, to say “how’s it going, how have you been?”, and be troubled half a second later, before coming back to normal conversation, one has to be really good!

She also does a formidable job with her voice and the intonations that sometimes betray the social origins of the character of Irène.

From time to time, we said it was necessary to pierce the bantering behind the luxury clothes. This was something that was not in the script and that Audrey came up with on her own.

When you were writing the script, did you already have Audrey Tautou and Gad Elmaleh in mind?

Yes. I was already thinking of Audrey’s imagination, of what she could suggest while playing the role. I had seen Gad in the theater, and I wanted to get an actor who could be almost invisible, neutral, and progressively acquire an elegance, a beauty, become a magician, someone who could manage in all kinds of situations. And, I also wanted someone who knew how to use his body well. A true body of slapstick comedy.

It was after I had seen Gad on stage that I wrote the introductory scene: Jean arrives into the frame carried away by a pack of dogs and one does not know if it is he who is walking them or, rather, if the dogs are walking him. From the onset, a shy character stands out, someone without real will or desire. He is someone who is lead. We also see that that this is a person who is a bit burlesque, already a party pooper, who upsets the order of things. At the same time, I filmed a lot of feet in this scene because I wanted to show how this character becomes more and more graceful, a kind of dancer… It is a scene that I love because all is said without a word.

In this scene, he advances almost despite himself.

Absolutely. By this first scene, I tried to impose the tone and the style of the film. In a screenplay, we try to imagine the scenes that are purely cinematic, scenes or situations which were meant to be filmed. Their value should not be literary. One must pursue dramatically rich situations and “expressive images” as Lubitsch said. It is this idea that one films an object and that it says something.

In PRICELESS, is it for example the Euro coin?

Yes. In my films, I often put objects that bring ambiguity to the characters, to their complexity or their destiny. These objects that often circulate in my films serve as a connection between the spectators and the characters.

How did this idea come to you?

I was looking for a way for Jean to tell Irène that he knows what she is and that it does not bother him. When he asks her for ten more seconds, to give her this Euro coin, it is a way to tell her with gentle irony that he knows who she is. It allows Jean to distill a dose of irony and, of humor, and to make himself charming… From that moment on, he becomes poetic.

Then, when Irène understands that Jean has become a gigolo, she gives him back the coin, meaning that he is now her alter ego. In that moment there is an almost fraternal bond between them. When they get rid of the Euro at the end, it is a way for them to get rid of a weight and particularly for her to get rid of her obsession with money. I felt that it gave closure to the film and that it was stylistically interesting…

Where did the character of Jean come from?

I often write about characters who are shy and anxious. The characters of Francois Cluzet in LES APPRENTIS, of Guillaume Depardieu in CIBLE EMOUVANTE, of Marie Trintignant in COMME ELLE RESPIRE all have a lot in common. They are characters who were upsetting to me. They want to be in the world while being unable to cope. They do not have “instruction manuals.” Like many of my characters, Jean is a submissive person, crushed by his shyness, whose desires will free him. For these reasons, I really needed Gad.

He is a cross between Keaton and Chaplin…

He looks a lot like Buster Keaton, with his eyes half closed and something old fashioned in his face. In the long shots, I wanted him to almost design his movements. And, he really liked working in this manner.

Jean is always caught up in his automatic reaction to being a waiter…

We did not want to make too much use of it, but it was irresistible! When one works for ten years doing something, one automatically reverts to that, like when he gets up after he hears a client hail “waiter” or when he grabs the bags at the hotel instead of letting the employee do it. It’s pure slapstick comedy. Finding this kind of scene always makes us very happy!

It’s the second time that I’ve created the character of a waiter. At the beginning of the film, one of his colleagues asks him why he always accepts extra jobs like “walking the clients’ dogs” He answers “I’m so used to saying yes that I don’t dare say no.”

It is the typical attitude of people who are so shy that they are almost submissive. It is embodied by the fact that he serves people. A free body! We were interested in the fact that his profession accentuates his self-effacing personality.

How did you write such natural dialogue?

The fact that I was an actor early on in my career allows me to play out the dialogue as I write it. If the words do not sound right, I rework them and rewrite them. There has to be music in the dialogue.

One of your distinctive features is to favor the `off screen’ space of the characters. This gives the spectator autonomy…

I like to leave part of the dramaturgy to the imagination of the spectator. When I speak about the euro coin as a point of connection between the spectator and the character, it is exactly that idea. I adore productions that are discreet and conceived to “be watched”: when Irène drinks a cocktail and puts the little paper umbrella in her hair, I prefer 100 times that she be seen later with five paper umbrellas in her hair rather than be seen drinking five times! The ellipsis is the path made by the spectator. In the real time of a movie, it is something that does not exist – it is a break, one tenth of a millimeter between two planes. It is what permanently binds the spectator to the film. It is also a game between the one who looks and the one who does. For me, it is the supreme art in cinema.

“I would love…I would like…” Can you comment on this recurrent line of dialogue?

Its significance changes while the words remain the same. When she doesn’t finish it, the line refers to a ruse and a lie, and, in the end she says “I would love, I would like,” and she ends the sentence by “to kiss you,” which sounds like the end of a lie. From a manipulative sentence, it turns into a sentence that expresses a naked truth, the confession of love. The sentence evolves at the same time as the characters. It is like rails, something which holds the story and gives it unity. It is kind of like a running gag.

During the shooting, does the direction play against the screenplay?

No. I only try to find all the ideas which can reinforce it. Sometimes you feel you have to free yourself, liberate yourself from that which is written because you feel you can do better. But, I never fight the screenplay; it is a support and an ally. The screenplay is prepared from the very beginning for the direction, to be cinematic. The ellipsis of the paper umbrellas was already in the screenplay.

For rhythm’s sake, you had to cut some scenes during the edit….

I rewrite a lot during the editing. I move, I eliminate, or rearrange certain scenes. It’s less and less difficult to separate myself from scenes I like a lot. There are actually two screenwriters for my films, my co-writer, Benoit Gaffin, and the editor, Isabelle Devinck. In fact, Benoit was not on the set, but he was present at each editing session.

You have a crew of loyal colleagues, in particular Gilles Henry, your director of photography….

Gilles, like most of the crew, has worked on all my films, even my short films. For PRICELESS, we worked with “chiaro oscuro” and day for night. I delegated more and more of the setup of the shots to him, which allowed me to really reflect on the direction. The shoot was the most liberating and interesting one I have ever done with Gilles. We know each other so well that we’ve reached a fascinating level of collaboration. He now knows the language I use when I make a film. It is invaluable!

You also worked again with Camille Bazbaz on the music…..

I had really liked one of her albums, and had asked her to write the music for COMME ELLE RESPIRE. When we met, we realized that we had a lot in common and similar tastes in music as well as in film. For PRICELESS, we said from the very beginning that we would create an original musical score.

Her work was very thoughtful; it combines the “rich” big band music in the luxury hotel scenes with a kind of musical sketch for the love scenes. For example, when they are on the beach, and Irène awakens and looks at Jean, there is only a guitar and a melodica (similar to a harmonica).

How did you choose Marie-Christine Adam who plays Madeleine?

It was Alain Charbit, the casting director who had asked her to audition. From the beginning, her scenes were fantastic. There was already a real sense of rhythm, an emotion. She can appear severe and hard and then all of a sudden, completely helpless. She made it impossible to hate the character because her loneliness surfaces all the time. I was very pleased to select her for the role.

What is your next project?

I don’t know. Sometimes I would like to do a crazy comedy, search for the perfect comedy series, something almost plastic. Just like some moments in Blake Edwards’ or Howard Hawks’ films.

Are these classic filmmakers important to you?

It used to be that when I was writing or screening a film, I was always a bit uncomfortable about quoting Ernst Lubitsch or Gregory La Cava or Mitchell Leisen. Now, I demand them loud and strong and never lose sight of them.

About Pierre Salvadori

With six films to his credit, French director/screenwriter Pierre Salvadori has built a cinematic universe of slightly offbeat characters in marginal situations. Like the protagonists struggling humorously against their shortcomings and life’s obstacles, Salvadori began his career as a cabaret actor in a modest local café-theater in Paris. Born in Tunisia, he embarked on his journey to the city at the young age of seven with his family. After completing secondary studies at the college François Villon, he continued onto classes in film and theater and jumpstarted his career by swiftly landing a screenwriting position for television sitcoms at AB Productions.

In 1989, Salvadori wrote his first screenplay entitled Wild Target which also marked his feature directorial debut. The film garnered the young director a César nomination for Best First Work, though he had already tested his directorial capabilities the year before with the short film Menage.

For his highly successful second and third features, The Apprentices (1995) and Commo Elle Respire (1998), respectively, Salvadori teamed up with acting favorites Marie Trinignant and Guillaume Depardieu, with whom he had worked on Wild Target. Depardieu’s performance in the The Apprentices earned him the 1996 César Award for Best Promising Actor. Following such acclaim, Salvadori switched gears with his next project, a dark thriller entitled The Sandman (2000).

Shortly afterwards in 2003, Apres Vous marked the director’s triumphant return to comedy. Boasting an A-list cast including Daniel Auteuil, Sandrine Kiberlain and Jose Garcia, Apres Vous mixed romance with farce in a charming debate about the pitfalls of being a Good Samaritan. Released by Paramount Classics, the film received a César nomination for Daniel Auteuil’s lead performance while solidifying Salvadori’s influence in French cinema.

Production notes provided by Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Priceless (Hors de Prix)

Starring: Gad Elmaleh, Audrey Tautou, Marie-Christine Adam, Vernon Dobtcheff, Jacques Spiesser, Annelise Hesme

Directed by: Piere Salvadori

Screenplay by: Benoit Graffin, Piere Salvadori

Release Date: March 28th, 2008

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for sexual content including nudity.

Studio: Samuel Goldwyn Films

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $2,165,188 (7.8%)

Foreign: $25,649,595 (92.2%)

Total: $27,814,783 (Worldwide)